End-of-life care is not unidimensional, nor is it delivered in a single setting. The context in which care towards the end of life is offered varies widely, both nationally and internationally. Emergency care is one such context in which professionals often offer services that respond to needs related to the end of life, whether they concern grief, bereavement or an imminent death. Therefore, paramedic practice is important in the provision of end-of-life care, especially when individuals are faced with an unexpected crisis. Brady (2013a; 2016) and Pettifer (2011) opine that paramedics play an important part in end-of-life care; however, they are often inadequately prepared because their training has historically focused on acute medical management and includes limited palliative care education (Kirk et al, 2017). The Social Care Institute for Excellence (2013) highlights that paramedics are often not made aware of end-of-life care priorities, choices and advanced decisions on refusing resuscitation. According to Lord et al (2012), this may create feelings of conflict in paramedics over their perception of their role, which can lead to professional uncertainties.

The connection between paramedic practice and end-of-life care is neither new nor unexplored. Pettifer (2011) found that more than 60% of paramedics will see a terminally ill patient on every or every other shift. This is a high percentage so it should not been taken lightly.

Despite the dearth of data in this area (Pettifer, 2011), we can assume that paramedics will also face a patient's family member or friend who is concerned about the progression of the patient's health and expresses grief on every or every other shift, as well. Equally, Parkinson (2014) points out that ambulance services are often the only choice patients have when community and 24/7 services are still inconsistent.

The Bradley report Taking Healthcare to the Patient: Transforming NHS Ambulance Services (Bradley, 2005) and Transforming NHS Ambulance Services (House of Commons Committee of Public Accounts, 2011) both recognised the significance of emergency care in end-of-life services, and highlighted the need for work in this field to evolve and for an increase in paramedics' expertise.

Theorists and researchers often highlight that the need for further education in palliative emergency services is pressing (Parkinson, 2014). Recent studies have argued that paramedics lack adequate education and training to undertake the task (Pettifer, 2011; Taghavi et al, 2012; Kirk et al, 2017). Specifically, research has shown that paramedics often experience uncertainty in their practice, especially when faced with legal and/or ethical dilemmas in this area, such as do not attempt cardiopulmonary resuscitation (DNACPR) orders (Taghavi et al, 2012). This is of critical importance, yet research is still lacking in this area to better acknowledge the needs of professionals.

Brady (2013b) argues that more research is needed around death, anxiety and emergency services. Brady (2013b) recommends that the proximity in which paramedics experience mortality causes unforeseen anxiety to them, which needs further exploration. This assertion may be unsubstantiated, yet remains relevant and in line with research in other disciplines, such as counselling or social work (Quinn-Lee et al, 2014). Very few studies have focused on the links between end-of-life care and paramedic practice; with most focusing on clinical decision-making processes and DNACPR orders (e.g. Wiese et al, 2012).

The present literature review explores current knowledge and evidence about paramedics' attitudes and perceptions about end-of-life care. It starts from the premise that, to advance end-of-life care in paramedic practice, it should be considered how professionals in the field connect to this part of their role and how they react to the reality that they could potentially be working in circumstances in which a patient dies or might die. This starting point links well with Brady's (2016) assertion that emergency services can significantly improve the quality of end-of-life service delivery.

Last, it is worth acknowledging the diverse terminology used in this field internationally. For the purposes of this article, the terms ‘paramedic practice’ and ‘emergency services’ are used interchangeably, as are the terms ‘paramedics’ and ‘emergency personnel’.

Methodology

Design

A systematic literature review was conducted as the best method for examining current published research (Booth et al, 2016). This type of review employs a systematic method of data collection (i.e. search and identification of literature that answers the research question) and data synthesis and analysis. It increases the validity of the review as well its chances of replicability—an essential aspect of validity in research (Silverman, 2016).

Systematic literature reviews are complex by nature, but they both review the current literature and uncover a research problem that needs further exploration (Machi and McEvoy, 2016), which is one of the current paper's aims.

Search strategy

Following an initial review of the current literature on the subject (Scott, 2007; Stone et al, 2009; Waldrop et al, 2015), search terms were generated (Box 1). Then, various combinations of these search terms were trialled before the authors settled on a broad search strategy, given the limited literature on the subject.

| *End of life (*care) | *Perceptions |

| *Death | *Out-of-hospital |

| *Dying | *Emergency |

| *Ageing | *Paramedics |

| *Elderly | *Pre-hospital |

| *Attitudes | *Palliative care |

| *Stances | *Hospice care |

| *UK |

The screening of articles was performed by the lead author and discussed with the second author. For screening purposes, the authors used the following criteria to assess individual papers (Hart, 2018):

Data sources

For the purposes of the present review, the following databases and platforms were searched: EBSCOhost (Medline, Academic Search Premier, PsycINFO and CINAHL), Sage, Taylor & Francis, PubMed and the Journal of Paramedic Practice. Reference lists of included papers were also searched. Appendix 1 shows the number of hits on each database, based on search terms. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were predetermined and applied during screening.

Inclusion criteria

The current review searched only for primary studies as the interest was in evidence that informs practice, policy and education or training. Primary studies included: explorations of the links between paramedic practice and end-of-life care in the UK; attitudes and perceptions of paramedics about end-of-life care, death and dying; current emergency practice in end-of-life care; as well as end-of-life care in paramedic practice. The review placed an emphasis on exploring research that developed in the past 10 years, starting in 2008. There are two reasons for this.

First, this would include all work that depicts paramedics' perceptions about end-of-life care since publication of the End of Life Care Strategy (Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC), 2008), which highlighted that care needed to extended across multidisciplinary teams. Equally, paramedic education and training in this area is scarce (Brady, 2016) but has increased in the last decade, especially since Taking Healthcare to the Patient: Transforming NHS Ambulance Services (Bradley, 2005), which explores the training needs of paramedics, and identifies the unique and irreplaceable role of paramedics in the healthcare system altogether.

However, one paper that was published in the 1990s (Smith and Walz, 1995) was found via the snowballing technique—it was in the reference list of one of the papers identified—and included in the review because of its pertinence to paramedic education and the current paper's aim.

Exclusion criteria

To capture the current empirical knowledge that informs practice, secondary studies were excluded from this review. Conference abstracts, other non-empirical papers (e.g. conceptual pieces), grey literature and non-peer reviewed articles were excluded for the same reasons. Furthermore, papers not published in English were excluded, because of the authors' language limitations.

The authors excluded flawed papers identified using the following quality appraisal criteria (adapted from Dixon-Woods et al, 2006):

Following the initial screening, each paper was scrutinised, using these criteria, before it was decided whether it should be included or excluded. Additionally, each paper was assessed against research rigour, generalisability, scientific contribution and relevance to the aims of the current literature review, before deciding on its exclusion or inclusion.

Analysis

The selected papers were examined by means of unit analysis (Miles et al, 2013). This method of analysis allowed the authors to methodically identify repeated patterns of knowledge and gradually examine the emerging themes from the present review. This said, a method of thematic analysis (Miles et al, 2013) was used to explore the themes and subthemes of the review, while the authors employed an interpretive review method to explore the concepts that were presented in the selected articles.

Results

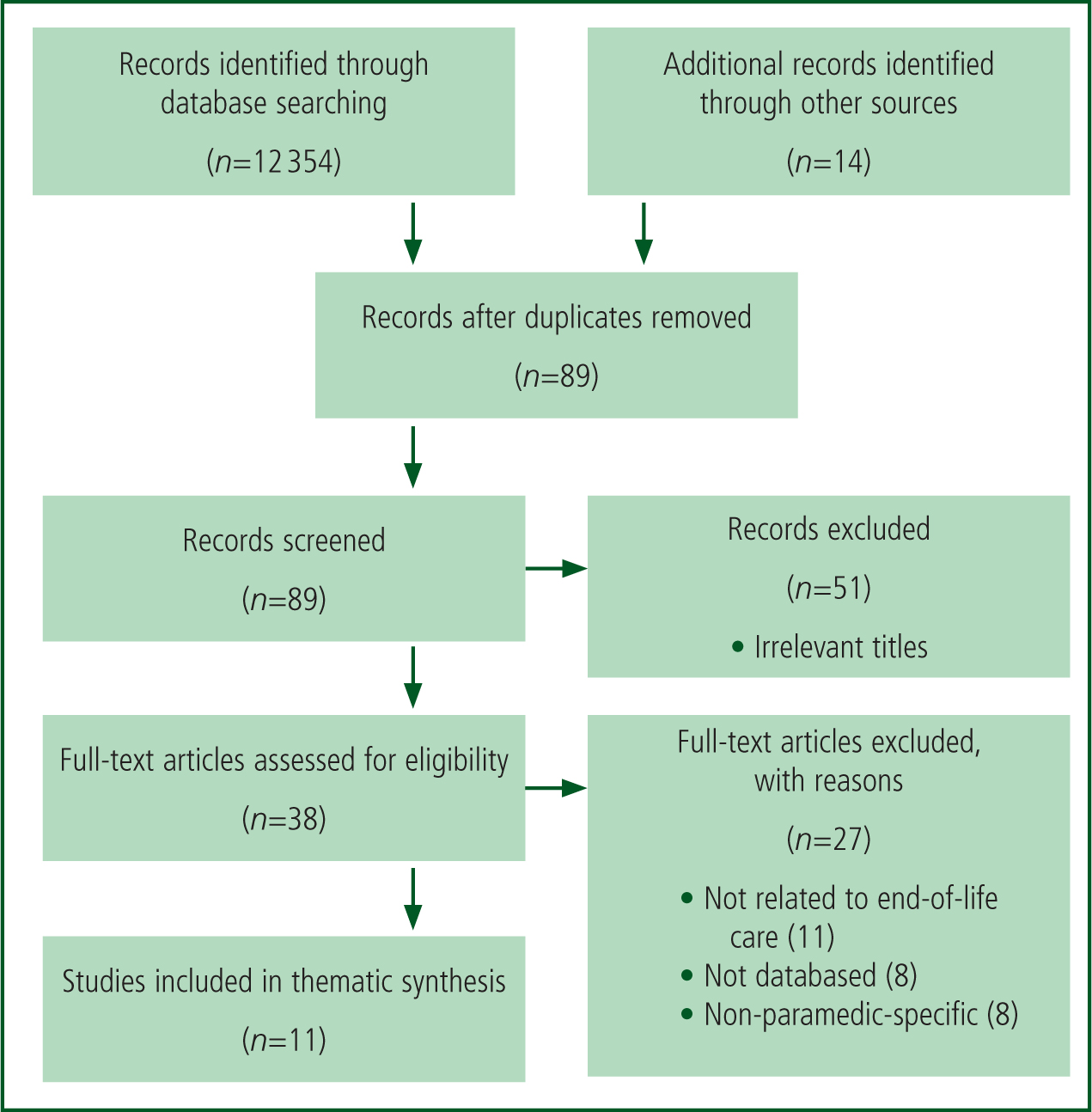

A total record of 89 papers were screened, but only 11 met the inclusion criteria after quality assessment as per the PRISMA statement (Moher et al, 2009) (Figure 1). The papers included studies undertaken in a few countries—four in the US, two in Germany, two in Australia, two in Canada and one in Israel. It is worth highlighting that no studies from the UK were found in this literature review. There was a balance of qualitative and quantitative studies—six and five respectively.

The studies reviewed for the purposes of this project recruited predominantly paramedics but also included educators in programmes for paramedics, as well as student paramedics. The studies conducted in the US used the term emergency medical staff instead of paramedics.

The studies that were considered for this review had a variety of outcomes. Predominantly, studies aimed to explore the coping mechanisms of paramedic staff who find themselves in situations when they need to provide end-of-life services (Douglas et al, 2013a; Barbee et al, 2016). Equally, studies focused on paramedics' attitudes towards advance directives (ADs) and DNACPR orders in the US (Waldrop et al, 2015) and Germany (Taghavi et al, 2012; Wiese et al, 2012), as well as towards older age and the care of elderly (Ross et al, 2015). The identification of the country of origin is important as legislation in the US is much more complicated than it is in Germany. In the US, state law applies as well as federal law; if an order is not legally valid in a given state, emergency staff do not need to follow it.

Studies also focused on: paramedics' response to critical incidents when on shift (Avraham et al, 2014); death education for paramedics (Smith and Walz, 1995; Douglas et al, 2013b); paramedics' perceptions about palliative care (Rogers et al, 2015) and end-of-life care generally (Stone et al, 2009) (Table 1).

| Author (year) Country | Study design and data source | Participants | Findings related to the aims of the current review | Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Avraham et al (2014)

|

Qualitative methodology. |

15 paramedics (5 women and 10 men) from one setting | The study presents two themes: paramedics find it difficult to connect with and later disconnect from a critical incident pertinent to the end of life (EOL) during a shift; second, when the outcomes of the event were negative, paramedics expressed feelings of lacking control | The study concludes that paramedics need to find a better balance between connecting with an incident and detaching from it to manage the situation and their role better, as well as increased emotional resilience |

|

Barbee et al (2016)

|

Qualitative methodology. |

98 emergency medical staff participated in eight focus groups | The study presents six emerging themes (coping strategies) from the focus group discussions: ‘soldiering on’ because of a lack of resources; peer support; seeking professional help; stress debrief at work; social support outside work; and personal forms of coping | Two general approaches were identified—avoidant and reflective coping strategies |

|

Douglas et al (2013a)

|

Qualitative methodology. |

28 paramedics (22 men and 6 women) contributed to four focus groups | Paramedics feel unprepared to undertake the task of death notification. Equally, they feel unprepared to manage the emotionality attached to the task | More support is necessary to better equip paramedics in the field |

|

Douglas et al (2013b)

|

Qualitative methodology. |

28 paramedics (22 men and 6 women) contributed to four focus groups | Paramedics feel unprepared to communicate death notifications | Training in this area and in EOL skills in general is minimal, so professionals are poorly prepared |

|

Ross et al (2015)

|

Quantitative methodology. Cross-sectional survey (three questionnaires across four universities) | 871 student paramedics in four universities in Australia | Most students demonstrated little knowledge about older people but their attitude was marginally positive | Further training seems necessary |

|

Rogers et al (2015)

|

Quantitative methodology. An online survey was distributed to all staff in a single area in Australia | 29 staff responded to the survey (21 were male) | Paramedics have a basic understanding of palliative care and holistic care | Paramedic education needs to consider ethical issues at the EOL and responsibilities regarding EOL care |

|

Smith and Walz (1995)

|

Quantitative methodology. |

537 coordinators of programme for paramedic education were sent the survey; 51% were returned | 95% of the programmes address aspects of death education, in a lecture format. Aspects are pertinent to ethical issues or legal matters. | More attention seems necessary when educating student paramedics before they go into the field |

|

Stone et al (2009)

|

Qualitative study; survey mailed to paramedics | 236 paramedics from two cities; Denver in Colorado and Los Angeles in California. Most (222; 94%) were men | There is a general agreement among paramedics that written advance directives should be honoured. A large majority of the participants felt unprepared to respond to EOL situations | EOL skills are not a priority in the education and training of paramedics. The need to further training and advance skills is highlighted |

| Taghavi et al (2012) Germany | Quantitative methodology. |

728 paramedics | Paramedics considered resuscitation at the EOL to be inappropriate. Also, they were uncertain about the legal complications around not attempting resuscitation; advance directives were considered important in emergency situations | More dialogue between disciplines is important to improve the decision-making process when offering EOL care in emergency situations |

|

Waldrop et al (2015)

|

Quantitative methodology. |

178 emergency medical staff, of whom 102 were paramedics | Prehospital emergency staff state that one is dying, when: a hospice is involved; there is a diagnosis of a serious illness; there is apnoea, mottling or breathlessness, as well as other medical conditions and symptoms that were not identified | The role of emergency medical staff members may be changing because of the ageing population. |

| Wiese et al (2012) Germany | Qualitative methodology. Self-directed questionnaire exploring paramedics' understanding of their role in withholding or withdrawing resuscitation/EOL treatment | 728 paramedics in two German cities (81% response rate) |

71% of participants deal with EOL and palliative care emergencies daily. |

Paramedics seem to lack legal skills and knowledge, and how these apply in practice. The authors identified a need for education |

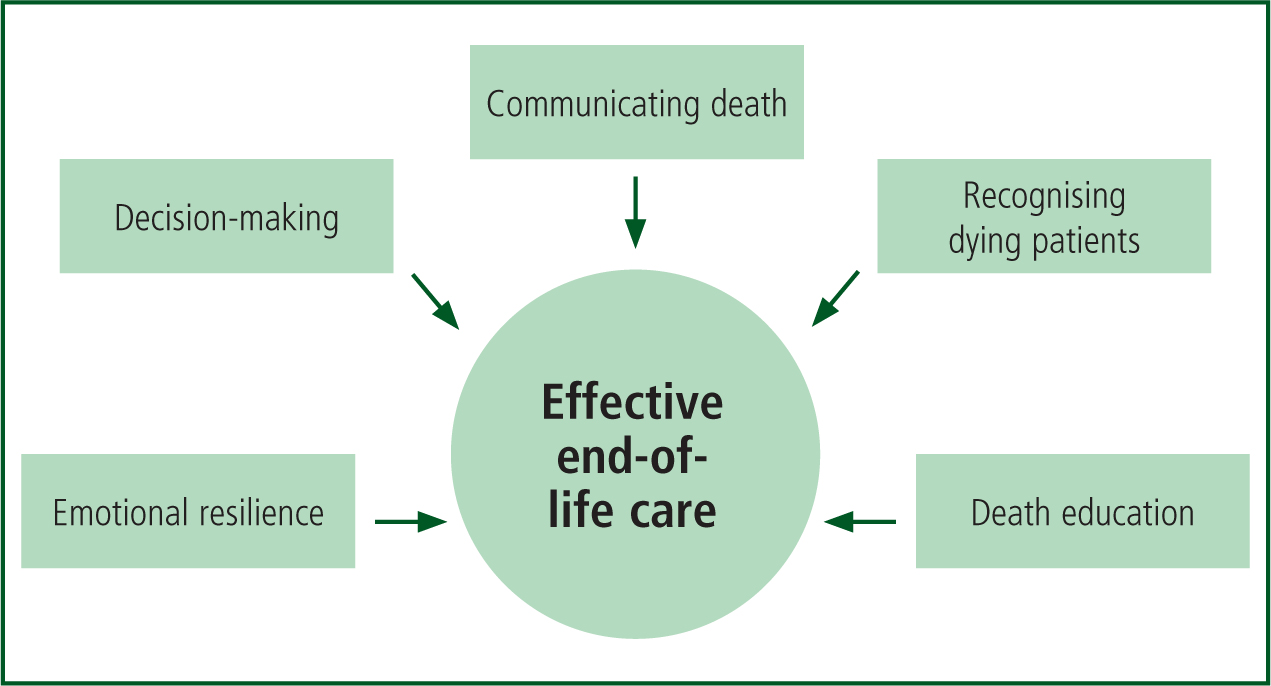

Following this thorough review of the papers, five themes emerged (Table 2), which are discussed in subsections below. The authors propose a model (Figure 2) that illustrates the interplay between the various themes and supports the conclusions of the current paper.

| Critical incidents and emotional resilience | Scott, 2007; Avraham et al, 2014; Barbee et al, 2016 |

| Decision making | Stone et al, 2009; Wiese et al, 2012; Taghavi et al, 2012 |

| Communicating death | Douglas et al, 2013a; 2013b |

| Recognising dying patients | Rogers et al, 2015; Waldrop et al, 2015 |

| Death education | Smith and Walz, 1995; Stone et al, 2009; Rogers et al, 2015 |

Critical incidents and emotional resilience

The studies that explored how paramedic practitioners respond to critical incidents—how they cope with the emotionality attached to many of the crises in which they get involved—all draw similar conclusions; they found that, despite the mix of coping strategies when working in end-of-life situations, paramedics continue to struggle with the emotionality attached to the various critical incidents in which they may be involved (Scott, 2007; Barbee et al, 2016).

In their study of how paramedics respond to crises, Avraham et al (2014) found that they struggled in two main areas: connecting with the event; and detaching from it later. Naturally, this leads to a discussion about emotional resilience and the abilities or opportunities to develop such abilities (e.g. training), to manage the emotions that emerge in such circumstances and remain detached from a personal perspective while maintaining a professionally committed and caring role in the situation.

Avraham et al (2014) concluded that, regardless of the management of emotions, when the outcomes of a situation were positive, paramedics would feel much more in control of the incident. However, when the outcomes were negative, they would feel they lacked control. Unfortunately, the authors did not identify the qualities of ‘positive’ or ‘negative’ outcomes, but suggested that a patient feeling better was a positive outcome. That said, a biomedical model of practice and perhaps little acceptance of the natural progression of life (i.e. death) seem to predominate here. This will be discussed more extensively.

Barbee et al (2016) focused solely on the coping strategies that paramedics displayed after they had been involved with an emergency, in which death was a possible outcome or was the outcome. They concluded that there are two types of coping strategies observed in paramedic practice—avoidant and reflective strategies—and both are equally evident. Furthermore, these authors found six coping strategies that more often emerge from paramedics' experiences: soldiering on because of a lack of resources; peer support; seeking professional help; critical incident stress debrief; social support; and personal forms of coping. The participants in the present study seemed to employ a mix of strategies.

Despite its indirect focus on the emotionality attached to crises, Barbee et al's (2016) study led to a discussion about resilience and the notion that coping strategies are essential if paramedics are to manage their emotional reaction to emergencies pertinent to end of life.

Decision making

Other studies focused on ADs, DNACPR orders or both (Stone et al, 2009; Taghavi et al, 2012; Wiese et al, 2012). Such studies were not only concerned with the perceptions of paramedics about these topics but also delved into an exploration of how ADs and DNACPRs impacted on decision making processes in emergency situations where end of life is pertinent.

Wiese et al (2012), for example, examined ADs and decisions not to implement ADs or not to resuscitate. They found that, even though paramedics consider ADs to be very helpful when in a critical situation, they found resuscitation orders to be ethically and legally confusing. Equally, Taghavi et al (2012) suggested that paramedics consider resuscitation at the end of life inappropriate, causing ethical concerns. On a similar note, Stone et al (2009) suggested that ADs are important at the end of life and should always be honoured.

Paramedics seem to struggle with DNACPR orders while feeling comfortable with the use of ADs. The main challenges observed in current literature are legal or ethical. The little research that is available on paramedics' perceptions about attempting resuscitation suggests there is uncertainty about the legal issues if resuscitation is not attempted (Taghavi et al, 2012; Wiese et al, 2012).

Similarly, it is evident from the studies by Stone et al (2009) and Taghavi et al (2012) that paramedics face significant ethical concerns pertaining to the decision to attempt resuscitation or not when an order is in place. This indicates the need for further and ongoing supervision in paramedic practice, which will be further discussed.

Communicating death

Douglas et al (2013a; 2013b) explored extensively how paramedics communicated death notifications and how they felt during the process. Douglas et al (2013b) suggested that paramedics were totally unprepared for this task and ethically challenged when in a position where they had to share information regarding a death notification or the death of someone overall. The same study suggested that paramedics were unprepared, lacked training in this area, and found it difficult to manage the emotional toll of the task of communicating death notifications (Douglas et al, 2013a).

Recognising dying patients

An important aspect of end-of-life care is the ability to recognise when a patient is dying (DHSC, 2008). Despite the simplicity of this statement, it remains highly complex as it concerns a willingness to accept a patient's deteriorating state and allow them the space to die.

Waldrop et al (2015) explored this area and found that paramedics struggled to clearly identify patients who were near the end of their lives. Furthermore, Rogers et al (2015) examined paramedics' perceptions about palliative care and found that paramedics associate palliative care, by and large, with a cancer diagnosis. However, they did not identify whether paramedics consider palliative care to be part of end-of-life care or vice versa.

Death education

Literature has also focused on educational programmes and the training needs of paramedic professionals. Smith and Walz (1995) recommended that 95% of paramedic programmes cover one or more aspects of death education; for example, ethical and legal issues in emergencies that are pertinent to the end of life.

However, more recent research (Rogers et al, 2015) suggests that paramedics may indeed have a basic understanding of palliative and holistic care but lack the confidence in skills proficiency, knowledge or expertise to offer end-of-life services when needed. This was also highlighted by Stone et al (2009), who suggested that a large majority of paramedics felt unprepared to offer end-of-life care when needed.

Discussion

Death education in paramedic programmes is crucially important. Paramedics are the emergency personnel who often respond to crises and are expected to be prepared to deal with many and varied situations in which patients may die, or family members or friends react unexpectedly and with tension to the circumstances. That said, paramedics are at the forefront of care, where their resilience and strengths, as far as end-of-life care is concerned, are constantly tested.

The notion of control becomes pertinent for various reasons, including the feeling of being helpful and achieving medically constructed goals The current review identified a professional struggle in paramedic practice: professionals follow a biomedical model, which constrains them from learning more and further in-depth from witnessing the unavoidability of death in life.

This becomes a barrier in itself and paramedics may feel they lack control over a situation because a patient dies. This is of no surprise though if one comprehends the advancement of paramedic practice as a medical emergency response to health issues (Lord et al, 2012).

This is one of the most important findings in the present review, as it highlights the need for further education and training to better conceptualise the potential loss of a patient in the field, and learn how to best manage the emotionality attached to such an event. This is reminiscent of Glasser and Strauss' (2017: 3–15) discussion about ‘awareness of dying’. Widely acknowledged challenges among health professionals, such as nurses, physicians and paramedics, are confidence in skills proficiency and knowledge, and identifying who is dying and when. This challenge is directly linked to professional vulnerabilities (Pentaris, 2018).

Health professions have moved beyond the intention to preserve life and prevent anything that threatens it (Stanfield et al, 2012). However, professionals remain challenged by the need to support or be comfortable in this; this challenge has emerged since the 1950s, and has evolved in contemporary societies (Papadatou, 2009).

Equally, the need for ‘awareness of dying’ solidifies a necessity to integrate the social model (Yuill et al, 2010) in paramedic practice, and explore the applicability of person-centred care (Wood, 2008) while delivering emergency services. Although this is an assertion, it is legitimised by the findings of the current literature review.

It is also important to emphasise professionals' uncertainties that emerge from the small amount of literature available (Brady, 2013a). Paramedic practice offers frontline services to people who are in a health crisis. In such situations, decisions are both impactful and quickly made. Decisions are made with the proviso that professionals who make them are fully informed and aware of the implications of their choices; whether legal, moral and ethical or health-related. Uncertainty in any of these areas—such as the legal or ethical implications of decisions that emerged from the present review—indicates incomplete or unsteady training, or the need for risk management in paramedic practice.

Sanders et al (2012) highlighted the need for educating paramedic students about the legal and ethical issues related to their future practice. The authors of the present study, similarly, imply how greater awareness of such issues may reduce the likelihood of burnout or emotional fatigue; this was also explored by Sofianopoulos et al (2011). This may be an area that requires extensive research but which has not yet been started, given the very recent acknowledgement of paramedic practice as a field in education and research.

Conclusions

This review has, most importantly, shown there is a gap in literature, as far as paramedic practice and end-of-life care is concerned. Given the nature and intentions of the profession, this is highly concerning, and makes the topic all the more pressing.

Paramedicine became a profession only in 2000 in the UK, when it was registered with the Council of Professions Supplementary to Medicine (CPSM). In 2001, the then British Paramedic Association (now the College of Paramedics) was formed and acted as the professional body for paramedics. Regulations and guidelines have emerged over the years, which have formalised and legitimised paramedics; these include Taking Healthcare to the Patient: Transforming NHS Ambulance Services (Bradley, 2005) and Transforming NHS Ambulance Services (House of Commons Committee of Public Accounts, 2011), as well as the Paramedic Curriculum Guidance Handbook (College of Paramedics, 2017).

In conclusion, paramedicine is a recently developed profession in the UK, which emerged as emergency care staff expertise had not been acknowledged. Because of its recent history, it would be unreasonable to expect an extensive body of research. However, given the pertinence of end-of-life care to paramedic practice and because paramedics are involved in everyday health care, including end-of-life care, it is more than pressing to engage in in-depth research and identify areas for improvement in this area, as well as how paramedics can excel.

Many paramedics, according to the reviewed studies, feel unprepared in dealing with the ethical, legal and clinical decisions within end-of-life care. It is worth noting, though, that no study from the UK met the inclusion criteria, so it would be risky to generalise widely. There is, nonetheless, a need for integrated education and training in curricula to enable paramedics to feel more confident and competent in dealing with complex end-of-life situations. The current article highlights this very reality and puts an emphasis on future research.

Limitations

The conclusions from this review are not without limitations. Worthy of attention is the restricted generalisability of its conclusions. The search of the literature identified studies primarily outside the UK, which raises questions over how far the findings can be applied to paramedic practice within the UK. Nonetheless, other sources (e.g. Brady, 2016) strongly suggest that emergency personnel lack expert knowledge and skills in end-of-life care in the UK. This leads to various inferences, including that the paper's conclusion applies to the UK to some extent.