Team-oriented training in health sciences education has historically focused on the principles of crew (or crisis) resource management as a means of addressing issues in healthcare team performance and patient safety. These programmes have primarily been developed for training ‘intact’ teams as a solution for improving patient safety (Paradis and Whitehead. 2018). Intact teams are those that have stable membership and members work/train frequently together (Salas et al, 2008). In addition, training for team-based competencies has been developed by borrowing from aviation, an industry similar to healthcare in that safety is critical, but different in important socioeconomic factors that make up ad-hoc healthcare teams (Sharma et al, 2011).

In contrast to intact teams are ad-hoc teams. These are common in healthcare, especially in emergency medicine, trauma care, prehospital care and surgery. They differ from intact teams in that members come together in an impromptu way to achieve a common goal, usually within time constraints and with inconsistent, advanced planning (Edmondson, 2003; Roberts et al, 2014; White et al, 2018).

Ad-hoc teams are often deficient in many of the behaviours and training routines of intact teams (Steinemann et al, 2011; Komasawa et al, 2018), making it difficult to find effective methods of training in team-oriented attitudes and behaviours (Salas et al, 2008; Petrosoniak and Hicks, 2013). Ad-hoc teams rarely get to see the collective value of team training, and therefore may not see training as instrumental to their performance (Salas et al, 2008). Most importantly, they rarely work frequently and consistently together and lack collective identity and cohesiveness, resulting in an inability to develop adaptive behaviours and anticipate each others' needs (Leach et al, 2009).

Work on interprofessional team unity often focuses on the concepts of social identity theory (Feitosa and Fonseca 2020). Social identity theory posits that individuals will favour members they identify with (are in their group) over those who are outside their group or who they cannot identify with.

Ad-hoc teams lack collective identity and unity. When teams are not united, they are no longer teams. If this is the case, are ad-hoc teams actually teams or just subgroups working together on a task (Feitosa and Fonseca, 2020)? How can the members of an ad-hoc team unite and form the relationships required to function effectively together as a team? It is suggested that these inconsistencies put ad-hoc teams at high risk of poor teamwork and communication, which are largely attributed to social barriers, differences in training and the environments in which they work (Roberts et al, 2014; White et al, 2018).

Several authors support the need for simulation-based education (SBE) programmes to design and implement curricula with objectives that focus on the social, cultural, interpersonal and relational aspects of team training (Paradis and Whitehead 2018; Blakeney et al, 2019; Brazil et al, 2019a; Tørring et al, 2019; Purdy et al, 2020a).

Paradis and Whitehead (2018) have encouraged addressing the power structures and hierarchies that create rigid professional identities and prevent collaboration in interprofessional work. Sharma et al (2011) have pointed out there is a lack of empirical work regarding the best way to approach simulation that includes a focus on the sociological aspects of interprofessional healthcare teams. They stress the importance of addressing socially ingrained behaviours if interprofessional simulation is to be meaningful and relevant.

Research on interprofessional ad-hoc team training requires a shift in focus towards understanding how simulation can provide an appropriate environment for building the social capital required for ad-hoc team members to form relationships and behaviours necessary to positively influence performance. Without this understanding, ad-hoc teams may remain disconnected, lacking trust in members, identity and a collective culture that supports team-based relationships that extend beyond collegiality (Purdy et al, 2020a).

The purpose of this review is to build an argument for the use of SBE as a primary means of addressing the sociological aspects of ad-hoc team performance. This is accomplished by reinforcing the dimensions of social capital as the precursor necessary to promote a meaningful network of relationships between individuals that form ad-hoc healthcare teams.

Coupling organisational and social sciences literature with that on health professions' education may carve the path necessary for interprofessional ad-hoc team training to produce the robust positive effects that health professions educators are seeking (Reeves et al, 2013; Zajac et al, 2020).

Concepts of social capital

Social capital is seen as a valuable asset to both individuals and groups within organisations or communities. The amount of capital an individual or group holds can shift as relationships change or lose value over time if those relationships no longer exist.

In prehospital care, for example, the importance of social capital has been identified at the individual level when students transition to the workforce (Kennedy et al, 2015), or at the community level when evaluating organisational performance (Andrews and Wankhade, 2015).

There are many variations in the definition of social capital, but all have a commonality in that social capital exists in the actual and potential resources individuals can use and benefit from, as a product of the network of relationships they hold (Bourdieu, 1986; Coleman, 1988; Nahapiet and Ghoshal, 1998; Burt, 2000; Putnam, 2000; Lin et al, 2001; Häuberer, 2010).

Social capital is built on the production and preservation of trust (Nahapiet and Ghoshal, 1998; Putnam, 2000) through social interactions that promote the establishment of social norms, reciprocity and facilitation of access to information among collective units (Häuberer, 2010). Putnam's (2000) definition of social capital espouses that social networks that build reciprocity and trustworthiness among individuals are those which are most likely to pursue shared objectives effectively.

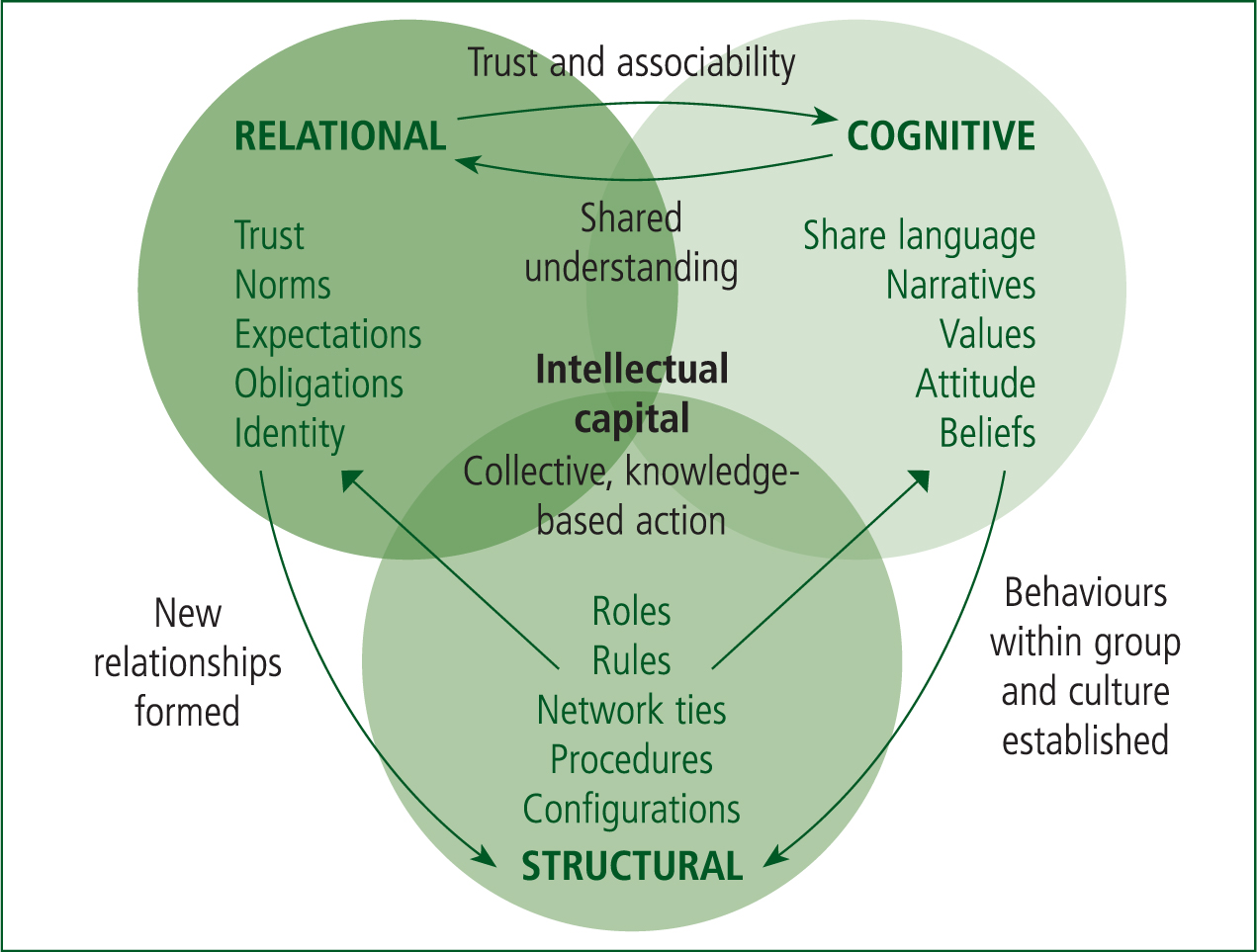

A commonly used framework by Nahapiet and Goshal (1998) divides social capital into three dimensions: structural; relational; and cognitive. Figure 1 illustrates the relation between the structural, relational and cognitive dimensions of social capital.

Structural social capital is tangible and easily observed through social structures and the formation of network ties, roles, rules, regulations and procedures. It is the precursor to other dimensions as it provides the structure for social exchanges to occur. This dimension relies on the properties of a social system and how an individual is able to interact with those with whom they have built connections inside this system.

Relational social capital is not tangible, as it involves the nature and quality of relationships and how individuals think and feel. Assets such as trust, norms, obligations, expectations and identities that are created and leveraged through relationships create relational social capital.

Cognitive social capital can be both tangible and intangible. The social setting or culture, shared understanding through language, narratives, goals, values, beliefs and clarity in group interpretations or meanings comprise the cognitive dimension.

The relational and cognitive dimensions feed back to the structural dimension by encouraging the formation of relationships, roles and rules through an inclination towards further socialisation. All three dimensions are interrelated and contribute to the overall formation of the social capital and collective intellectual capital necessary for knowledge-based action (Nahapiet and Ghoshal, 1998).

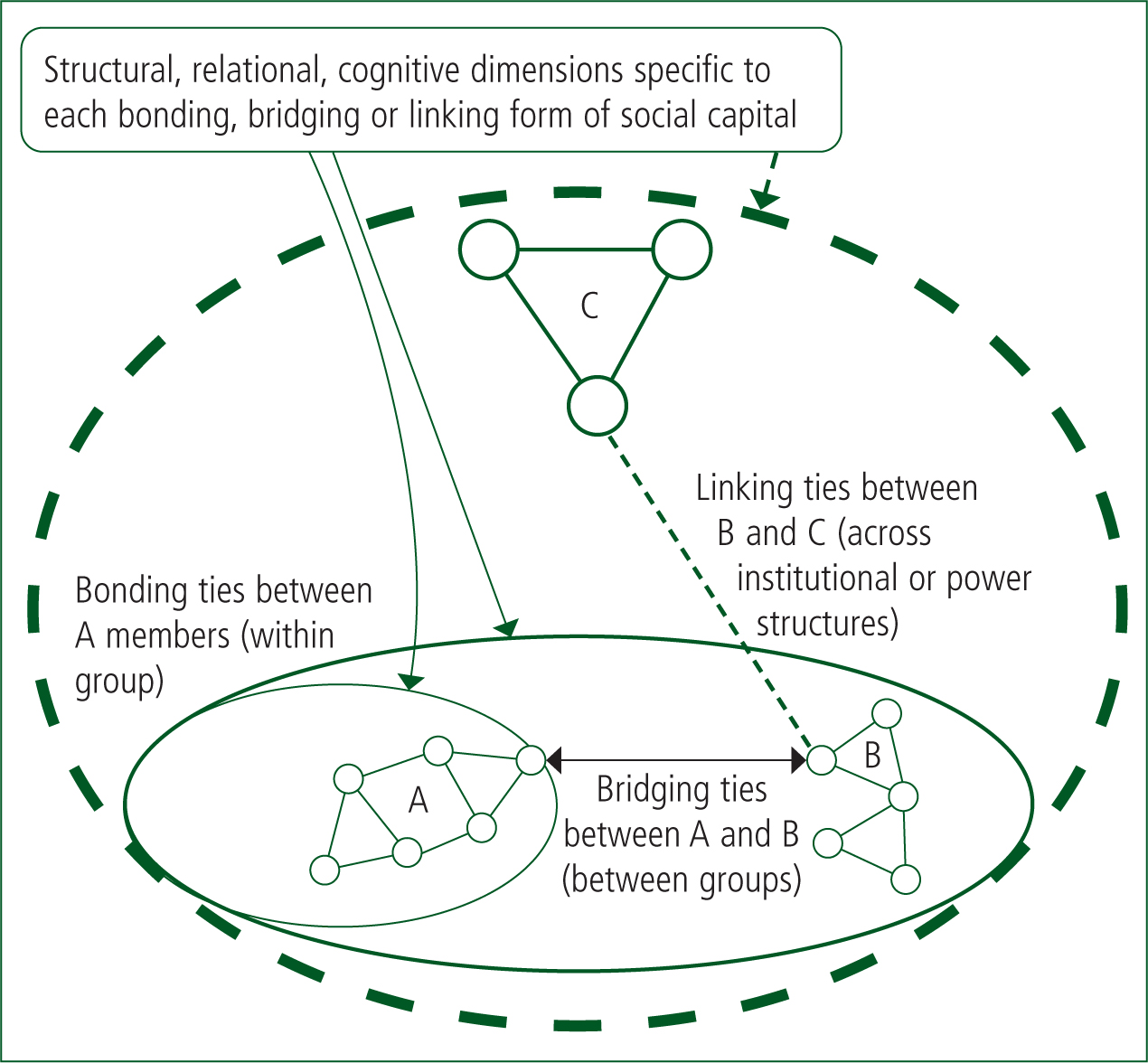

Two distinct forms of social capital influence the strength and type of relationships or network generated—bridging and bonding (Putnam, 2000).

Bonding social capital is exclusive in nature and constitutes the social ties most immediate to an individual within their ‘like group’. Bonding is the glue needed for trust, loyalty, reciprocity and the mobilisation of cooperative, collective action.

Bridging social capital is inclusive and concerns the establishment of relationships between different groups or hierarchies towards forming broader identities, sharing information and creating mutual trust and respect.

A third form—linking social capital—has been identified as important for those interacting across institutional power or authority gradients (Szreter and Woolcock, 2004). Linking social capital is similar to bridging but creates equity and reciprocity through the development of trusting and respectful ties between groups from different power structures.

All three forms are important to building ad-hoc team social capital throughout a healthcare organisation. Figure 2 illustrates bonding, bridging and linking forms of social capital.

Organisational social capital is an important resource that is realised when members of the social unit are able to facilitate collective action as a result of high levels of collective goal orientation and shared trust (Leana and Van Buren, 1999). Under collective action, groups and their members pool resources, knowledge and efforts to reach a goal shared by all parties (Häuberer, 2010). This form of social capital is therefore considered an attribute of the entire unit, not just the sum of one individual's collective social capital. However, an optimal balance of the interests of the individual interests and those of the collective group is required to grow this form of social capital (Putnam, 2000). Individuals must feel they have something intrinsic to gain by contributing to the collective action of the group.

Organisational social capital is built on two primary components of the relational dimension—associability and trust (Leana and Van Buren, 1999).

Associability occurs when participants set aside their own goals and actions associated with them to adopt those of the collective group. For there to be strong associability, group members need to be able to act socially with one another and do so with a willingness and desire to put the group objectives over their own. When this is achieved, collective identity, collective culture and behaviours that benefit the group (such as goal driven division and coordination of work) are seen.

Trust is more complex. Sometimes, it is required as a precursor for participants to work together collaboratively (Nahapiet and Ghoshal, 1998), and sometimes it is built as a result of successful collective action (Leana and Van Buren, 1999).

Social capital relies on the formation of generalised trust between individuals in the group that is resilient to negative experiences, predictable and built upon norms and values (Häuberer, 2010). Trust must be established that is not built upon specific individuals in the group but should be generalised to the collective unit or units within the group. Strong social capital within a system fosters generalised trust, meaning there is resiliency in this trust even if individuals within a unit are unfamiliar. This form of trust is critical for ad-hoc teams, as the composition of their teams at any point will be made up of varying individuals yet will most often have the same professional or disciplinary representation.

Regardless of the form or framework used, it is important to understand that social capital is shared between those who hold relationships with one another, that it maximizes efficiency of action by minimising weak ties and encourages cooperative behaviour, particularly when there is a high degree of trust between members (Coleman, 1988; Nahapiet and Ghoshal, 1998; Putnam, 2000).

Using simulation to build social capital

Studies of the impact social capital has on team-based relationships are infrequently cited in the health sciences education literature. Bourdieu's theories have been briefly discussed in the development of paramedic interactions, professionalism, and identity (Johnston and Acker, 2016).

Lee (2013), Cleland et al (2016), and Harrod et al (2016) have also identified the importance of building social capital, identifying that high levels of social capital in healthcare teams are influenced by how long members have worked together on a team (Lee, 2013) and by simply providing space for individuals to interact on a more personal level (Cleland et al, 2016; Harrod et al, 2016). Working together for long periods of time improves bridging and bonding relational network ties and facilitates ‘open communication, trust, liking, and shared cognition through an increasing amount of interaction’ (Lee, 2013: 85).

This socialisation has occurred through participation in SBE and other social activities during boot camps (Cleland et al, 2016) or coaching sessions away from clinical work (Harrod et al, 2016). These findings are central to the argument that the individuals who comprise ad-hoc teams may require frequent interactions to build up the social capital necessary for positive interprofessional team behaviours during composition for real-life events.

Simulation is a socially complex teaching and learning activity (Dieckmann et al, 2007), but the use of simulation in relationship formation and culture building in healthcare is not yet well studied (Purdy et al, 2020a). Well-designed simulations follow a structured approach to ensure the outcomes expected are achieved. It can be argued that a well-designed simulation programme that provides routine interprofessional training for ad-hoc teams can facilitate the development of collective identity, cohesiveness, associability and generalised trust by enhancing bonding, bridging and linking social capital between individuals and groups.

Evidence-based approaches suggest including the following in the design of SBE: a needs assessment; measurable learning objectives; structuring the format appropriately; contextual case development; appropriate fidelity; a participant-centred approach; prebriefing; following up the experience with debrief and feedback; evaluation; providing preparation materials; and pilot testing (INACSL Standards Committee, 2016).

Ensuring there is adequate time in simulation for individuals to build social capital is key in laying the groundwork required to focus on improving team-based relationships.

The next section of this review will highlight key components of well-designed simulation that foster building social capital.

Simulation programmes must make it a priority to establish norms that are conducive to information sharing and trust development (Feitosa and Fonseca, 2020). Routine interprofessional ad-hoc team simulation provides access to the structural, relational and cognitive dimensions of social capital. When formatted appropriately, it provides a structural place for individuals to interact socially and form relationships they otherwise would not have the opportunity to if interactions were only in ad-hoc team formation for clinical situations.

Brazil et al (2019b) suggest repeated exposure to one another through simulation may build relationships simply by learning names and more regularly seeing faces. Harrod et al (2016) have drawn similar conclusions, stating that structured time for professionals to interact in a space away from clinical work as important in building a sense of cohesion and support. Recognising a face from past simulation could mean less effort and time is needed for effective cooperation in clinical settings.

Cognitive social capital is built in SBE by developing shared languages, creating group narratives, discussing common goals and providing clarity in group interactions or meanings. The relational dimension is built during SBE through the establishment of trust between members, discussing expectations and the formation of collective identities that are supported by strong leadership and recognition that feels positive.

Simulation also provides an avenue for the relational and cognitive dimensions to be improved by allowing individuals to share their personal capital (their own knowledge and skills) with the rest of the team. By sharing personal capital, an individual can enhance role clarity and demonstrate to team members the importance of their role in achieving collective goals. For example, a senior team member may be able to share valuable experience, and a junior team member could impart current knowledge of evidence-base practice from their recent vocational training (Johnston and Acker, 2016).

Social interactions that bridge different professions or disciplines and build trust lead to the desire for more social interaction, further enhancing cognitive social capital. This in turn improves the relational dimension of social capital by creating multifaceted identities and reciprocity norms (Putnam, 2000), perpetuating the cycle.

Prebriefing and debriefing

Simulations and briefings should be designed to promote trust-building and associability through positive socialisation. Teams with high levels of social capital do not see knowledge, skills and abilities as belonging to one person but to the entire team and as valuable resources to be shared. This is key.

Well-established simulation programmes such as those described by Brazil et al (2019a) show evidence of having a profound impact on relational coordination and the development of collaborative culture among trauma team members. It is suggested this may have occurred in their programme simply through familiarity and routine participation in briefings (Purdy et al, 2020b).

Prebriefing and debriefing also provide an opportunity to build social capital through discussion and reflection on micro level behaviours that may prevent positive relationships from forming (Tørring et al, 2019). Educators must structure simulations for ad-hoc teams with specific learning objectives that focus on building targeted dimensions of social capital and use debriefing strategies that specifically address the relational aspects of teamwork demonstrated during simulation.

Simulation debriefings designed to promote reflection by both individuals and groups have been shown to improve culture and relationships that extend into real world practice (Brazil et al, 2019a). When debriefings are framed using the dimensions of social capital with facilitators trained in interprofessional co-facilitation strategies, they can facilitate discussion and interaction that target bridging and linking social capital by breaking down hierarchal barriers. This allows all participants to be heard and understood.

Using debriefing strategies that incorporate cultural-history activity theory to bridge the sociocultural differences in rules, norms, and customs between interprofessional team members may be a useful approach (Eppich and Cheng, 2015).

Simulation programme development

To facilitate the development of social capital through simulation, educators should adopt a social-constructivist form of pedagogy, and view their role as one of creating a ‘safe environment in which knowledge construction and social mediation are paramount’ (Adams, 2006).

Social constructivism emphasises the value of social collaboration in learning. It argues that learners are primarily motivated by the reward of providing knowledge to their group or community, as well as their internal drive to understand and be engaged in the learning process.

Taking a ‘guidance over instruction’ pedagogical approach is important for those participating in simulation-based medical education. Participants need to be able to learn from each others' professional differences, co-construct a shared knowledge of tasks and establish common goals. The educators must promote a process that encourages social interaction between participants for this to occur. Educators should play supportive role and position themselves as co-learners in debriefings and reflection (Fanning and Guba, 2007). Taking this position will encourage productive learning when debriefing objectives focus on discussion about behaviour changes necessary for building social capital.

Sharma et al (2011) recommend a more consistent implementation of simulation that addresses sociological factors such as hierarchy, power relations, interprofessional conflict and professional identity. During interprofessional ad-hoc team training, psychological and environmental fidelity may be difficult to replicate, as members of different professions or disciplines will have a variety of perceptions of what is ‘real’ to them. The simulation needs to have social interactions that reflect the situation as it occurs in reality (Dieckmann et al, 2007). This can be achieved through the use of in-situ simulation. In-situ simulation is a valuable means of conducting interprofessional simulation-based education (Steinemann et al, 2011; Brazil et al, 2019a; Gardner et al, 2020) and has been shown to generate improvements in rapid response team performance (Rule et al, 2017).

In-situ simulation comes with a high degree of psychological fidelity (Armenia et al, 2018), and requires fewer resources than off-site simulation in a specific simulation laboratory. As a beneficial addition, in-situ simulation can help ad-hoc teams identify latent sociological and relational threats to their performance that may not have been found in a different learning environment (such as a simulation lab) or not until real-life situations occur (Zimmermann et al, 2015).

Paradis and Whitehead (2018) suggest learning activities that promote contact between professions should address implicit interprofessional hierarchies and equalise status to promote collaboration. This would improve bridging and linking social capital or form new bonding social capital within the ad-hoc team group.

Formatting in-situ simulation so it ensures time for social interaction at an appropriate location may be the solution to these criticisms. It may require only a small room or hallway after in-situ simulation where people to gather and interact. Socialisation can then occur naturally or with facilitation during prebriefing and debriefing phases of the simulation.

These social interactions should not be delayed until a person is in professional practice. Students who may work on ad-hoc teams should be included so they can start to build social capital and work on building interprofessional relationship networks before they enter professional practice (Hall, 2005; Kennedy et al, 2015; Cleland et al, 2016). Programme developers should consider integrating simulation with other forms of social engagements. Suggestions include workshops, regularly scheduled meetings or extracurricular social events (Lee et al, 2019) that are organised specifically for members of ad-hoc teams including students within an organisation, and are ancillary to clinical work (Harrod et al, 2016).

Conclusion

Ad-hoc team training requires more than addressing the classic principles of crew resources management. If teamwork, leadership, shared decision-making and team mental models are to develop, relationships between team members must first exist. These team skills are based on communication, and communication relies heavily on cooperative and trusting relationships.

For this to occur, ad-hoc team members first need a learning environment that supports strengthening relational networks. Learning environments that provide a place for individuals and groups to build social capital with a high degree of generalised trust and associability is the first step in this process. Simulation is the environment for these relationships to develop, and the place where behaviours that either help or hinder this process are addressed.

More empirical research on the sociological outcomes of interprofessional simulation training is needed. Using social capital theory as a framework for developing ad-hoc team simulation training programmes is a novel means of building evidence to support or refute the impact social capital may have on interprofessional team training interventions (Lee et al, 2019).

Future research on simulation-based education should aim to analyse social capital in the context of ad-hoc team performance and the means of measuring social capital in simulation. If the social factors that underpin team performance remain overlooked, ad-hoc teams may never reach their peak performance potential.