LEARNING OUTCOMES

After completing this module the paramedic will be able to:

A healthy blood pressure is vital to life and both low and high blood pressure can be life threatening. This article looks at how the body regulates blood pressure, what a healthy blood pressure is, how it should be measured and what happens when blood pressure rises or falls. Paramedics may see patients who have a previous diagnosis of hypertension or who have suffered the devastating consequences of undiagnosed and uncontrolled hypertension, such as myocardial infarction and stroke (Law et al, 2003). Hypotension may be a presenting sign in conditions such as haemorrhage, both obvious as in the case of trauma and concealed as in the case of a slow gastro-intestinal bleed (Dutton et al, 2002), and may also be a sign of chronic disease such as neurological or endocrine disease (NHS Direct Wales, 2013). It is therefore important to understand how to recognise possible causes of blood pressure changes, understand how these fluctuations occur and how to measure blood pressure accurately in order to assess the patient's condition.

Regulation of blood pressure

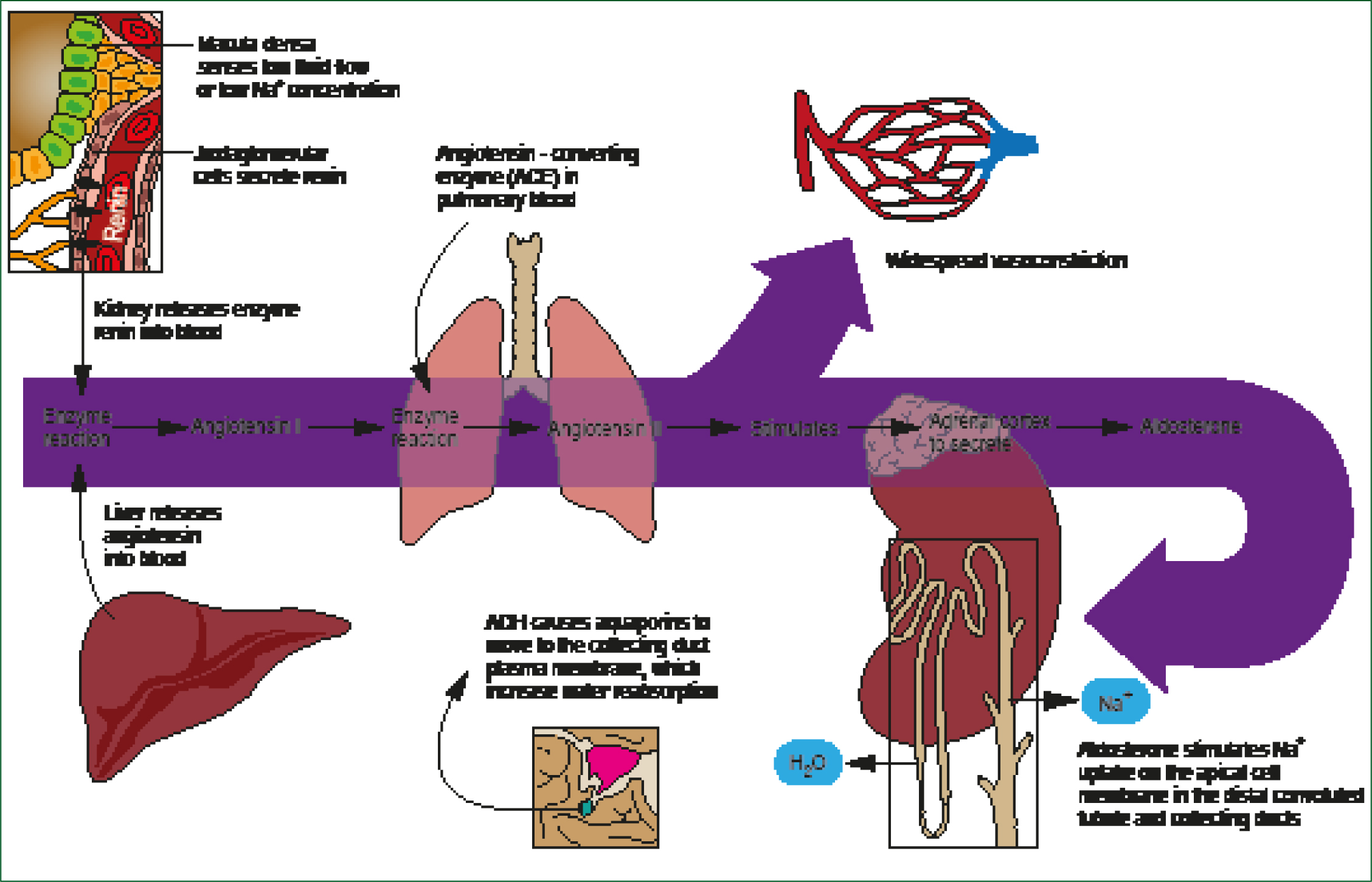

The body relies in the main on two key systems to ensure that blood pressure is maintained at the correct level to meet the body's requirements. In the longer term, the renin angiotensin aldosterone system (RAAS) influences sodium and water levels in the body and also affects vasoconstriction (Klabunde, 2007) (See Figure 1). In the shorter term, the autonomic nervous system works via the parasympathetic and sympathetic systems to adjust the heart rate and cardiac output when the body requirements alter suddenly (Siegfried, 2002).

The autonomic nervous system

The autonomic nervous system (ANS) has two branches: the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) and the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS). The SNS is the body's ‘fight or flight’ system. In a situation where the blood pressure needs to rise quickly, the SNS uses adrenaline (epinephrine) and noradrenaline (norepinephrine) to increase cardiac output by raising the pulse rate, whilst at the same time encouraging vasoconstriction (Siegfried, 2002). In essence then, the SNS causes heart rate and stroke volume to rise and vasoconstriction to occur and will be active in raising blood pressure; conversely, the PNS causes heart rate to slow down and stroke volume to fall and vasodilation to occur, leading to a reduction in blood pressure. Running for a bus or taking an examination will lead to activation of the SNS and an increase in pulse rate, blood pressure and cause vasoconstriction.

The renin angiotensin aldosterone system (RAAS)

The body responds to a drop in arterial blood pressure by activating both the RAAS and the sympathetic nervous system (SNS). These systems encourage fluid and salt retention and vasoconstriction in order to increase the circulatory volume. As its name suggests, the RAAS is located in the kidneys and its function is to ensure that adequate amounts of blood reach the kidneys to ensure that filtration, reabsorption and excretion of key substances (proteins, glucose, urea) in the body is carried out effectively (Atlas, 2007). If blood pressure is inadequate for this purpose, this will be registered via baroreceptors located in the aortic arch, carotid arteries and other areas of the cardiovascular system, and also by the juxtoglomerular cells in the kidneys (Krafts, 2012). These juxtoglomerular cells secrete renin in response to the low pressure and this rise in renin causes angiotensinogen from the liver to be partly activated to form angiotensin I. Angiotensin I is a fairly weak substance, however, and needs to be converted into the potent vasoconstrictor angiotensin II through the activity of an enzyme known as angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) (See Figure 1). This also activates the aldosterone pathway of the RAAS, which will result in further sodium and water retention and vasoconstriction. All of these activities lead to an increase in the blood pressure.

Normal, high and low blood pressure

Blood pressure is measured in millimetres of mercury (mm/Hg). Normal blood pressure can vary, although cardiovascular events have been seen to rise once blood pressure readings increase past 115 mm/Hg systolic (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2011). According to NICE, a blood pressure of over 140/90 mm/Hg is considered to be high (NICE, 2011), and a blood pressure below 90/60 mm/Hg is considered to be low (Dutton et al, 2002). However, an otherwise healthy individual may be able to tolerate a blood pressure as high or as low as this without any ill effects, whereas someone with a long-term condition such as coronary heart disease, heart failure or chronic kidney disease will be at risk of further complications if the blood pressure is not maintained at a healthy level (NICE, 2008; 2009; 2011). In people over the age of 80 years, a blood pressure below 150/90 mm/Hg is acceptable, as demonstrated in the Hypertension in the Very Elderly Trial (HYVET) (Beckett et al, 2008).

Hypotension is usually defined as a blood pressure of 90/60 mm/Hg or below. In an emergency situation, hypotension may be the result of shock and/or haemorrhage. However, in the non-acute setting, low blood pressure may be associated with long-term conditions such as Parkinson's disease, heart failure and Addison's disease (Senard et al, 2001). As previously noted, however, a sustained systolic BP of less than 115 mm/Hg is associated with reduced cardiovascular risk (NICE, 2011).

Postural hypotension is an important cause of symptoms such as dizziness, fainting and falls, especially in the elderly (Bostock-Cox, 2013). It is diagnosed if a drop in BP of greater than 20/10 mm Hg is measured within three minutes of standing (Lahrmann et al, 2010). Postural hypotension is thought to affect almost one third of adults aged over 65 years (Logan and Witham, 2012), but in neurological disease where the autonomic nervous system is affected, such as Parkinson's disease, the prevalence rises to almost two in three patients (Lahrmann et al, 2010).

Measuring blood pressure correctly

The British Hypertension Society (BHS) has issued guidance which highlights the importance of measuring blood pressure correctly, whether the person measuring the blood pressure is using a mercury sphygmomanometer or a digital machine (BHS, 2012). Although many healthcare personnel will consider themselves to be fully competent in this task, research has demonstrated that a large proportion of people who measure blood pressure regularly are ‘unknowingly incompetent’ when it comes to performing this task (Minor et al, 2012). It is essential, then, that everyone involved in measuring blood pressure knows how to do this correctly.

Key points to remember when measuring blood pressure include:

Implementation of this advice will depend on the given situation and in an emergency situation it may be inappropriate or even harmful to follow this general guidance. Each individual event will require an appropriately tailored approach.

Measuring blood pressure in patients with an arrhythmia

Digital blood pressure monitors may be inaccurate in people with arrhythmias and the BHS advice is that a mercury sphygmomanometer should be used in these individuals so that the sounds can be auscultated. Again, this may not be possible in the emergency situation and it is therefore important to be aware of the limitations of a digital monitor in people with abnormal rhythm patterns such as atrial fibrillation (BHS, 2012).

As hypertension can be symptom-free for years, it is important to proactively seek out people who may have undiagnosed hypertension, even if that is not directly related to the reason they are being seen at the time. People over the age of 40 should be reminded that they should have their blood pressure measured at least every five years (NHS Choices, 2012). As previously mentioned, an acceptable blood pressure in people under the age of 80 years would be 140/90 mm/Hg or below, whereas in people aged 80 years and above, the cut-off point should be 150/90 mm/Hg. Perhaps surprisingly, many healthcare professionals remain unaware to the status of systolic blood pressure (as opposed to the diastolic) as the key predictor of cardiovascular risk when it comes to blood pressure. Members of the public too may focus on the diastolic blood pressure reading as being the ‘important’ one. However, blood pressure is a key component of cardiovascular risk and the most widely used risk engines for assessing the risk of a cardiovascular event in the next 10 years only ask for the systolic blood pressure readings (British Cardiac Society et al, 2005; D'Agostino et al, 2008; Hippisley-Cox et al, 2008).

Diagnosing hypertension

Hypertension is defined as a sustained rise in blood pressure above 140/90 mm/Hg (NICE, 2011). This means that BP must be raised on more than one occasion for the diagnosis to be made. NICE therefore recommends that further measurements are made following a finding of raised BP of 140/90 mm/Hg or above on two separate occasions, unless the reading is so high that it warrants being labelled as severe hypertension, which can be an emergency. If the BP is found to be raised in a non-emergency situation, patients should be advised to have ambulatory or home readings recorded in order to ascertain what is happening to their blood pressure outside of the clinical setting. This will help to identify classical hypertension and white coat hypertension, and determine the best course of action for that individual.

How ambulatory and home blood pressure readings are used to make the diagnosis of hypertension

One of the key changes made in the latest guidelines on hypertension (NICE, 2011) was the way in which hypertension is now diagnosed. NICE now recommends that if the initial reading by the clinician is raised, home blood pressure readings should be carried out before the diagnosis is confirmed. If an individual has a new finding of raised blood pressure, referral for further assessment, including home readings, should be made. Home blood pressure readings can be measured in two ways when making a diagnosis of hypertension. Ideally, an ambulatory blood pressure monitor (ABPM) will be available from the patient's practice to allow them to be monitored during their waking hours (as opposed to the 24 hour monitoring that was previously recommended). The monitor will be set to record at least two BP readings every hour during waking hours. Once it has been removed at the end of the monitoring period there must be at least 14 readings available to provide a reliable overview of the BP readings. An average of these readings is then calculated, on which treatment decisions can be based.

If ABPM is not available or is unacceptable to the patient, home blood pressure monitoring (HBPM) may be carried out using a digital machine. Readings should be taken twice daily, morning and evening, for a week, with two readings being taken each time. Once the week's readings are available, the first day's readings should be discarded and an average of the remainder calculated. This reading should provide the basis for diagnosis and decisions regarding management. In the case of a patient who is found to have raised blood pressure during the paramedic consultation, advice to see the GP could be accompanied by advice to carry out home blood pressure readings up until they are able to get an appointment to be seen.

Severe hypertension—a crisis?

If systolic blood pressure is 180 mm/Hg or more, or diastolic BP is 110 mm/Hg or more, this may constitute a medical emergency in some individuals, yet in others may be something that can be followed up by the general practice team. To differentiate between the two, further assessment should be made before deciding which patient falls into which category and how and where to treat. In rare cases, severe hypertension may require immediate treatment in hospital. Signs such as papilloedema, confusion or cerebellar signs, including ataxia, require admission (NICE, 2011). If these are not evident, home monitoring may still be appropriate and these readings are often far less worrying. Research has shown that not treating asymptomatic patients with severe hypertension had no adverse effects in the first three months, so it may still be appropriate to refer the patient back to the practice so that readings may be continually assessed via ABPM or HBPM in the way described above (Kessler and Joudeh, 2010).

Conclusions

The definition of normal, high and low blood pressure can be made on absolute numbers, but the impact of that label will alter from individual to individual, depending on the circumstances in which the blood pressure is measured and the background health of the person concerned and their age. The British Hypertension Society has published guidance on how to measure blood pressure correctly to ensure any diagnosis pertaining to blood pressure (and in particular hypertension) is made correctly and treatment started appropriately. The role of the paramedic in monitoring blood pressure will reflect these individual circumstances and actions taken should be appropriate to each situation. Monitoring and addressing both low and high blood pressure is a key part of the role of the paramedic and understanding how and when to refer on, both in the acute and non-urgent setting, allows resources to be used effectively.