The UK ambulance service has experienced many changes over the past 10 years, shaped to a large extent by national policy documents including High Quality Care For All (Darzi, 2008), Equity and Excellence (Department of Health (DH), 2010) and most recently, Transforming Urgent and Emergency Care (NHS England, 2013). These policy documents identify the need to improve the quality of pre-hospital care and to increase the level of skilled intervention provided by ambulance clinicians.

It is important that the improvement of services and care should be informed by evidence. A lack of research-orientated ambulance clinicians has led to pre-hospital care and clinical guidance being predominantly informed by evidence from other professions (Association of Ambulance Chief Executives, 2013). This paucity of evidence is particularly apparent in the pre-hospital care of children. Many children cared for in the pre-hospital context require procedures and treatments which can be unpleasant and cause children to experience increased upset, distress, fear and vulnerability. This paper reports on a project which focused on the pre-hospital care of children during clinical procedures.

Background

Clinical procedures such as blood glucose measurement, administration of medicines and the application of dressings can cause children to experience upset, fear and anxiety, expressed through crying, aversive movements and comfort seeking (Rodriguez et al, 2012; Craske et al, 2013; Shockey et al, 2013). This procedural distress can be experienced in the absence of painful stimuli, due to a child's anxiety associated with clinical procedures (Craske et al, 2013). Children's experiences of procedural distress can cause long-term negative effects including lower pain thresholds as the child progresses through adolescence and into adulthood (Koller and Goldman, 2012), and diminished psychological well-being throughout life (Chang et al, 2012; Peterson and Noel, 2012), and can influence their future engagement with health professionals and services (Lambrenos and McArthur, 2003; Nilsson et al, 2009). Children's distress during procedures can be exacerbated if they are held, against their wishes, for the procedure to be completed (Darby and Cardwell, 2011). Despite evidence to suggest that the holding of children for procedures causes distress and upset to children, parents (McGrath et al, 2002) and professionals (Hull and Clarke, 2011), it continues to be an uncontested part of paediatric practice, with alternatives to holding often not being explored (Bray et al, 2014; Coyne and Scott, 2014).

Currently, there is a low level of robust pre-hospital research or bespoke evidence-based guidance which focuses on the care of children during procedures. Evidence indicates that ambulance clinicians may lack confidence (Houston and Pearson, 2010) and expertise (Roberts et al, 2005) in dealing with paediatric emergencies (Dawson et al, 2003), possibly due to the infrequent requirement for critical intervention with children (Jewkes, 2001). This project aimed to explore the influence of an education session on ambulance clinicians' self-reported confidence and ability to engage, treat and deal with any procedural distress experienced by children. The education session was delivered by health professionals with multi-disciplinary backgrounds and expertise in dealing with and managing children's distress within hospital settings. The content of the presentations included the use of distraction and managing procedural distress (Table 1), and was delivered through factual information, videos depicting children's experiences of undergoing procedures, and question and answer sessions.

| Title of session | Delivered by | Content |

|---|---|---|

| Distraction in children undergoing clinical procedures | Senior play specialist | Describing distraction Range of techniques Patient experiences Value of control and choice Evolving distraction |

| Procedural distress | Clinical nurse specialist (pain and sedation) | Procedural distress described Effects of mismanaged distress in children Physiology of fear/anxiety Reducing or eliminating procedural distress |

Methods

This project aimed to understand the influence of an education session on ambulance clinicians' self-reported confidence, understanding and opinions of caring for children undergoing clinical procedures. A mixed method design was used, with the intent to gather different but complementary sources of data (Cresswell and Clark, 2011). Structured quantitative data from questionnaires and qualitative data from focus groups were collected sequentially (Sandelowski, 2000).

Questionnaires

The questionnaires collected structured data through closed questions and Likert scales responses with the option to provide additional text at certain points. The development of the questionnaires was informed by pre-testing (with 35 ambulance clinicians), to check that the design and content had sufficient internal validity (Boynton and Greenhalgh, 2004). Following this, slight amendments took place relating to consistency of language and additional response options added to the multiple-choice answers. The questionnaires were administered immediately prior to the education session and again at the end of the session. Four core questions dealing with ambulance clinicians' confidence, children's distress, the use of distraction and the use of holding when caring for children, were the same on both questionnaires to enable direct comparison. Two additional questions were added to the post-educational session questionnaire, to gain information on the ambulance clinician's perception of the session.

Focus groups

Focus groups, conducted after the educational session, aimed to explore ambulance clinicians' perceptions of the education session along with their personal experiences of dealing with children's distress during clinical procedures. Collecting this qualitative data aimed to gain an understanding to inform practice (Then et al, 2014) and enabled an exploration of the beliefs, perceptions and subjective experiences of participants (Moule and Goodman, 2009). Ambulance clinicians were able to use their own words to develop ideas and questions based on incidents they had attended. The focus group discussions were informed by a semi-structured guide, which focused on ambulance clinicians' perceptions of the education session and experiences of caring for children undergoing procedures in pre-hospital care. The focus groups were moderated by two advanced paramedics who had in-depth knowledge and experience of pre-hospital care, but who were not directly linked to the delivery of the educational session. The focus groups were conducted concurrently in two large rooms, with sufficient space between each group to avoid overhearing other conversations; each group discussion was audio-recorded.

Sampling and recruitment

This project engaged with a convenience sample of ambulance clinicians who attended a regional clinical quality forum—a regular educational initiative. The attendees had a range of ages, gender, clinical experience and skills. This maximum variation was intentionally used to gain differing perspectives from participants (Creswell and Clark, 2011). Attendees registered for an educational forum advertised in a Trust-wide bulletin and were formally invited to participate in the project at the opening of the educational session.

Ethical considerations

As the project was focusing on local practice, and would be developing a baseline of practice, the Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership (HQIP) guidance (HQIP, 2011) defined it as service evaluation. The project was approved by the relevant Trust and university research and ethics committees. The participants were provided with an information sheet about the project before attending the education session. The completion of the questionnaires, and the participant's involvement in the focus groups, was voluntary. The completion of the questionnaires was anonymous and consent was assumed by their return. Written consent was obtained from those who participated in the focus groups and clear ground rules were established prior to data collection.

Analysis

The quantitative data from the questionnaires was analysed using simple descriptive statistics (Vaismoradi et al, 2013) through the use of frequencies and percentages. The focus group discussions were transcribed verbatim and checked for accuracy. The qualitative data was analysed using thematic analysis (Green and Thorogood, 2004); this involved the coding of data by ascribing labels to sections of text, followed by the organisation of the codes and data into themes (Vaismoradi et al, 2013).

Findings

The questionnaire and focus group data will be presented as two separate sections.

Questionnaire data

In total, 28 ambulance clinicians attended the education session. The pre-session questionnaire achieved a response rate of 92% (n=26). Ambulance clinicians were given the option to disperse following the education session; this meant the post-test questionnaire achieved a diminished response rate of 65% (n=17). For transparency, the numerical data includes both the response and number of respondents.

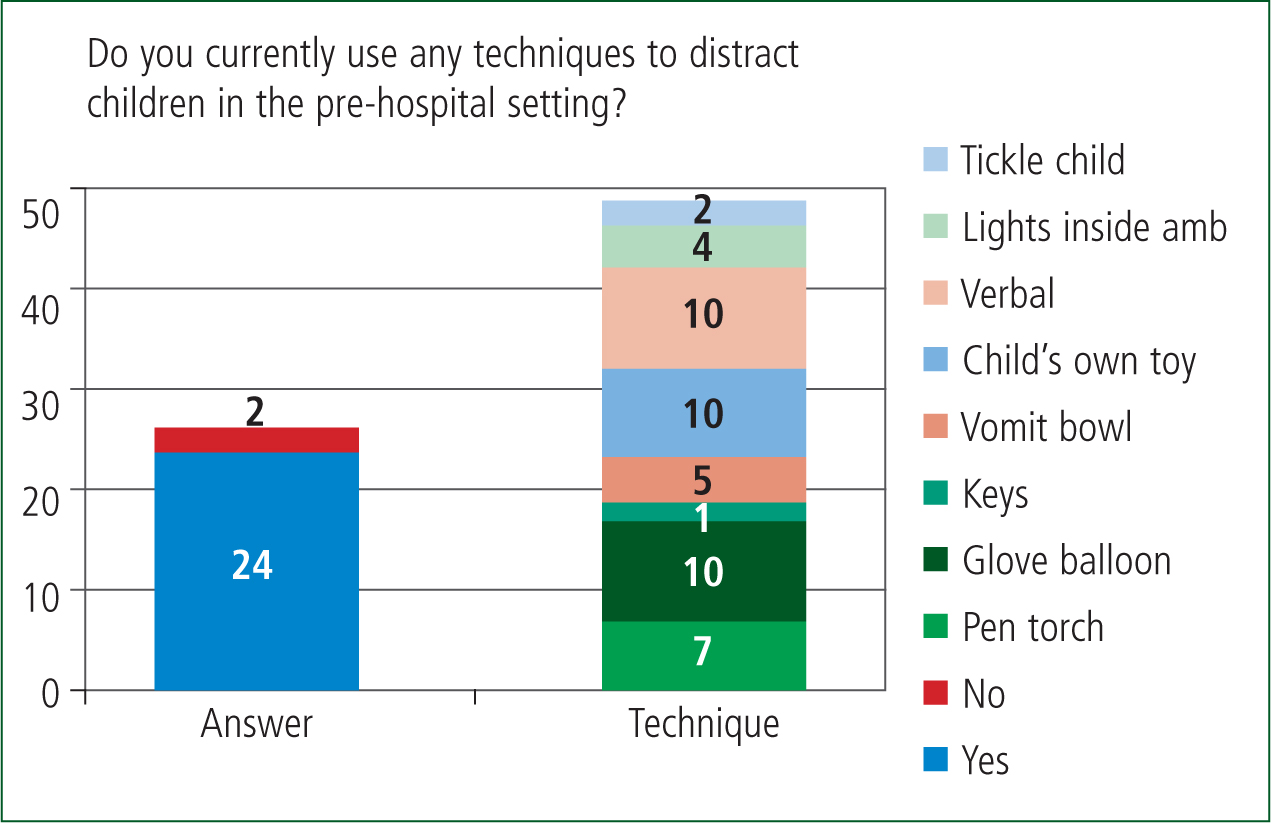

Ambulance clinicians were asked before the education session, in a closed question, how often they used distraction techniques and if they did, what equipment they used. The data shows that ambulance clinicians report using distraction techniques widely (92%, n=24/26) and techniques have been adapted to suit the pre-hospital environment. In the absence of specific distraction equipment, ambulance clinicians described the use of vomit bowls, keys and children's own toys in an attempt to generate a positive care experience for children (Figure 1).

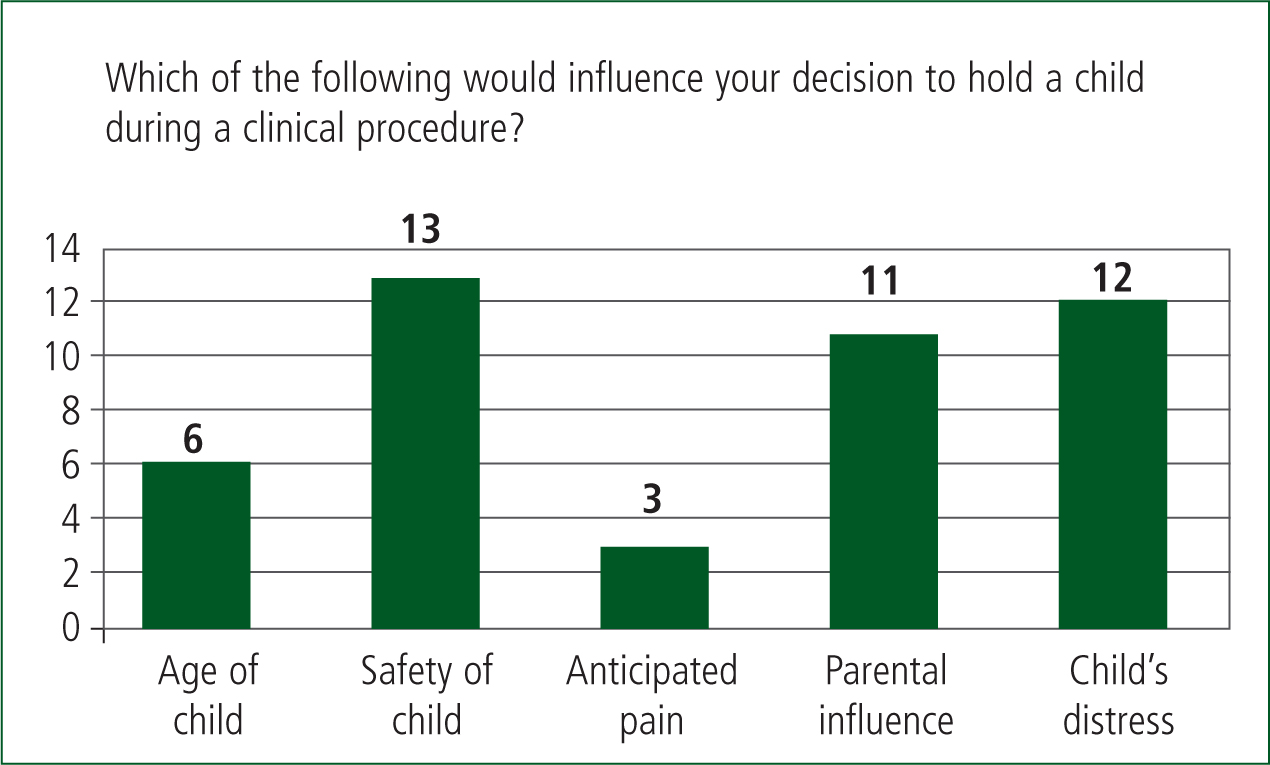

The participants were asked in a multiple choice question: ‘If a child needed to be held for a clinical procedure to be completed whom would usually do this?” Most ambulance clinicians (96%, n=25/26) answered that they would ask a parent or carer to hold their child in order for a clinical procedure to be undertaken. They were then asked: ‘Which of the following would influence your decision to hold a child during a clinical procedure?’ (Figure 2). The possible responses were: the child's age, safety of the child, anticipated pain, parental influence, and the child's distress. The safety (n=13) and distress (n=12) of a child were the most frequent responses, although ambulance clinicians acknowledged the influence of parents on how children were held during procedures (n=11).

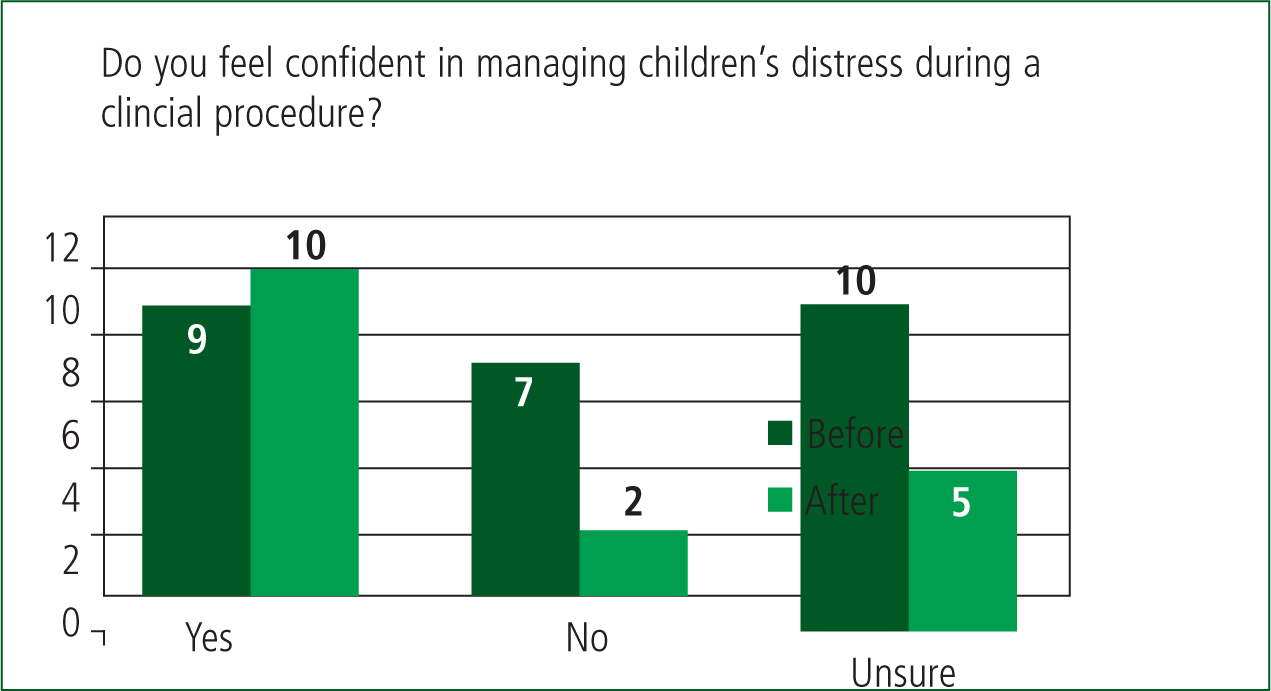

Ambulance clinicians were asked before and after the education session to score on a Likert scale how confident they felt in managing children's distress during clinical procedures (Figure 3). A decrease in response rate between the first (n=26) and second (n=17) questionnaire should be kept in mind when interpreting the results within this project. Following the education session there was a decrease of those who felt unsure (26%, n=7/26 before to 14%, n=2/17 after) or lacked confidence in dealing with children's distress (38%, n=10/26 before to 14%, n=2/17 after) and a slight increase in those who felt confident (n=9, 35% before, n=10, 58% after) (Figure 3).

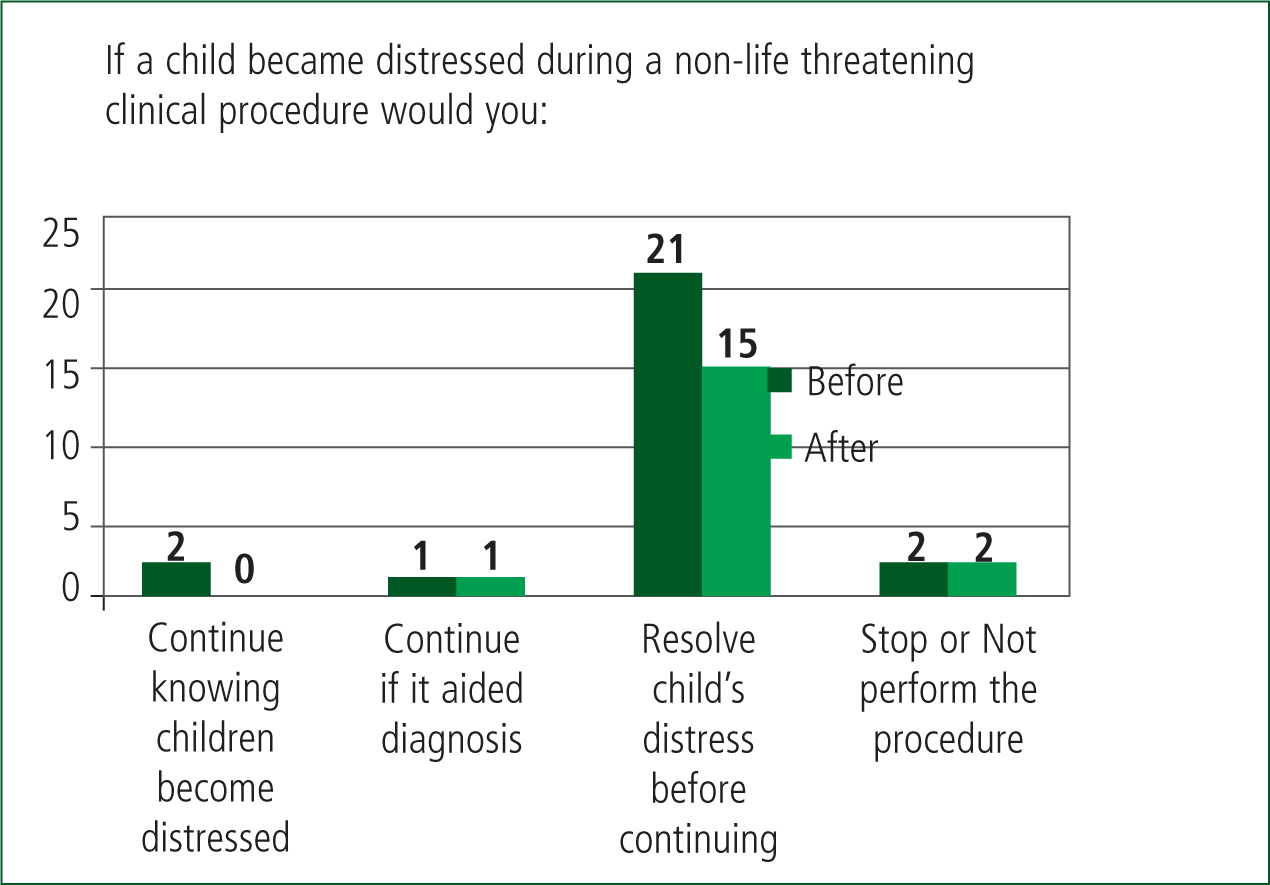

The ambulance clinicians were also asked in a multiple choice question before and after the education session how they would respond if a child became distressed during a non-life threatening clinical procedure. There was little difference noted in how ambulance clinicians would respond before or after the educational session (Figure 4), although there was a slight decrease in those who would continue with a procedure despite high levels of distress (n=2 before, n=0 after).

Focus groups

Four focus groups were held with a total of 20 participants (20/28, 76%); the four groups had six, five, five and four participants in each. The findings are presented under the three main themes which developed from the analysis: current practice, distraction techniques and clinical holding. Much of the discussion which ran through the focus groups related to the challenge of balancing the value of a procedure against the potential distress caused, and the ambulance clinicians discussed at length the aspects of current practice which could cause tensions or difficulties. They discussed specifically how the education session had been useful in prompting them to challenge one aspect of current practice, the taking of blood glucose (BM) samples from children.

‘I get quite irritated by staff members that just routinely do a BM on a child, they don't consider the history or even think about why they're doing it, it's just a figure that they want to put in a box to make sure that they pass audit’ (FG3).

Many of the ambulance clinicians discussed that the presence of the national febrile children audit had led them to carry out procedures without exercising any critical thought or common sense. This contrasted with the accounts of some ambulance clinicians who highlighted how it was important to balance the diagnostic or therapeutic value of a procedure against the potential distress it may cause a child.

‘Most important is…don't do it if you don't need to’ (FG3).

Each of the focus groups included a discussion around the use of distraction techniques and how any distraction equipment would need to be designed specifically for use in the pre-hospital setting.

‘Well maybe rather than something that's portable, because portable things get lost and small things, but if we had something that was built into the ambulance like a controllable light’ (FG1).

The ambulance clinicians discussed how there were specific issues to working in pre-hospital settings which made established distraction techniques such as bubbles not appropriate.

‘Now you've got the health hazard with bubbles, slip and trip. More slip than trip’ (FG1).

There was limited discussion of children having to be held for clinical procedures and interventions, although the ambulance clinicians did acknowledge that in some cases parents lacked the confidence to hold their child during a clinical procedure.

‘Yeah and the kids sat there like: “I'm fine”. I've had a mum get off the ambulance before while I've cannulated the kid I know because she was so scared of needles her kid was about seven and needed chlorphenamine’ (FG4).

This supports the questionnaire data which suggest that ambulance clinicians rely on parents to hold their children during clinical procedures. It is unclear whether the lack of discussion was because this is not a feature of pre-hospital care or whether it is an invisible and unquestioned part of practice.

‘Both questionnaire and focus group data suggest that ambulance clinicians felt more confident and had an improved understanding of children's distress following the education sessions’

Discussion

This project set out to evaluate the influence of an education session on the reported confidence and ability of ambulance clinicians to engage, treat and deal with children undergoing clinical procedures in the pre-hospital setting. The use of mixed methods supported both the collection of numerical data and a more focused exploration of ambulance clinicians' qualitative perceptions of the education session and their experiences of managing upset and distress in children who require clinical procedures.

Ambulance clinicians report frequently using distraction during procedures with children, and seem adept at adapting common, everyday items for this purpose. The ambulance clinicians in this project recognised the worth of distraction in reducing children's anxiety and upset during clinical procedures (Koller and Goldman, 2012; Sadeghi et al, 2012). The environment of the pre-hospital setting provides unique challenges to using distraction techniques—space is limited and techniques which are used widely in acute settings would not be suitable for use in an ambulance. This creates difficulty in the translation of evidence from acute services to the pre-hospital environment. This project has highlighted that ambulance clinicians are keen to engage in distraction techniques and there are opportunities to develop context specific equipment. Further work is needed to more clearly define the extent to which distraction techniques permeate pre-hospital practice in the UK.

This project aimed to evaluate the influence of an education session on ambulance clinicians' understanding of children's distress and the use of distraction. Both questionnaire and focus group data suggest that ambulance clinicians felt more confident, and had an improved understanding of children's distress, following the education sessions, although for some aspects this was minimal. This supports previous work which has shown that education can positively influence the clinical skills of ambulance staff (Byars et al, 2011; Deluherey et al, 2011). Although it is recognised that brief education sessions are an adjunct to improving confidence and competence, they need to be supported by continued input and practice-based training, to ensure that learnt skills and knowledge directly impact on the development of a more compassionate approach to pre-hospital care provision, as described within current political agendas (Francis, 2013; NHS England, 2013). Frequent skill application should still be considered the gold standard, as education is no substitute for technical expertise gained through clinical practice with children (Glasper et al, 2009).

A key aspect of practice discussed by many of the ambulance clinicians, was the need to balance causing upset and distress in children against undertaking necessary clinical procedures. Part of a national clinical performance indicator (CPI) metric for pre-hospital care requires a blood glucose measurement on all febrile children. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) (2013) guidance on febrile children makes no such recommendation, thereby calling into question the inclusion of this invasive and sometimes distressing procedure within a pre-hospital care quality metric. Participants discussed how they felt more confident after the education session to delay a procedure if it was likely to cause a child distress, but felt tension against the perceived need to complete key audit data.

Ambulance clinicians did not report any tensions relating to children being held for clinical procedures, although seemed averse to holding children themselves for clinical procedures. Data gained during this project indicates that the majority of ambulance clinicians look to parents/carers to hold their child for clinical procedures. The discussion during the focus groups indicated that holding children for clinical procedures occurs frequently but is an unexplored area of practice in pre-hospital care. Work is now underway to address concerns that the practice of holding children appears to be openly uncontested in pre-hospital care.

Limitations

The term ambulance clinician has been used throughout this work, due to a mix of clinical grade across participants. It is therefore not possible to describe the findings as representative of paramedic practice, but more broadly indicative of pre-hospital practice. The complexity of literature surrounding holding children for clinical procedures meant that participants were not guided on a definition of holding. This could mean that ambulance clinician's perceptions of holding were inconsistent, which may undermine some of the responses provided. The small sample size and geographical spread of participants may limit the generalisability of these results. The study is limited by only accessing the views of ambulance clinicians who actively chose to attend an education session, and did not collect data from the wider ambulance service.

Conclusions

This project has demonstrated that ambulance clinicians can be uncertain of how to manage children's distress during clinical procedures, but report the wide use of distraction techniques to try and reduce any distress and provide a positive experience for children in their care. This small project suggests that education sessions can have value in helping ambulance clinicians to question their practice, and highlights the need for additional empirical work to examine how clinical procedures involving children are managed within the pre-hospital setting.