The future direction of emergency care will extend ambulance service responsibilities and increase the need for evidence-based paramedic-initiated interventions (NHS England, 2015). Although services welcome opportunities to improve patient care, paramedic involvement in the development of new treatments and processes is hindered by a number of factors including traditional professional boundaries and a lack of standardised training that reflects pre-hospital clinical and research responsibilities (Wood, 2012; Ankolekar et al, 2014).

For instance, it is expected that clinicians supporting research will regularly complete good clinical practice (GCP) training to reinforce and update principles of research governance, but as the content originates from hospital-based pharmaceutical trials, it does not routinely include study designs used in the pre-hospital setting or specifically focus upon the narrower role played by ambulance service personnel. Many influential pre-hospital trials do not involve traditional consent processes, or randomisation to a new medication. The research responsibilities of ambulance personnel are further constrained by time-limited contact with patients, and in the context of clear guidance from modern study protocols, they are unlikely to need the same in-depth knowledge of research governance frameworks as a hospital-based investigator.

It is also an important practical consideration that within the broad clinical population served by ambulance services, only a relatively small proportion of patients will be eligible for a specific study. A large number of paramedics usually require training for ambulance Trusts to assist with efficient study completion, but due to high service demands it is extremely challenging to ensure that the workforce is constantly up to date using traditional classroom delivery (Burges Watson et al, 2012). A requirement for all ambulance service personnel to regularly undertake formal GCP training will impede growth of the pre-hospital evidence-based practice, and may not be necessary in the context of new study designs and well-defined roles and responsibilities.

Aims

This project was funded by the North East and North Cumbria Academic Health Science Network, with the aim of developing easily accessible research governance awareness training tailored towards the role played by paramedics and other ambulance personnel. This was achieved through an initial systematic literature review to establish research training practices across the pre-hospital domain. Secondly, a national survey of paramedics ascertained their level of preparedness to assist with clinical research. Finally a Delphi-style exercise was performed to achieve consensus among ambulance research leads and academics regarding the content of generic governance training materials.

Methods

Systematic review

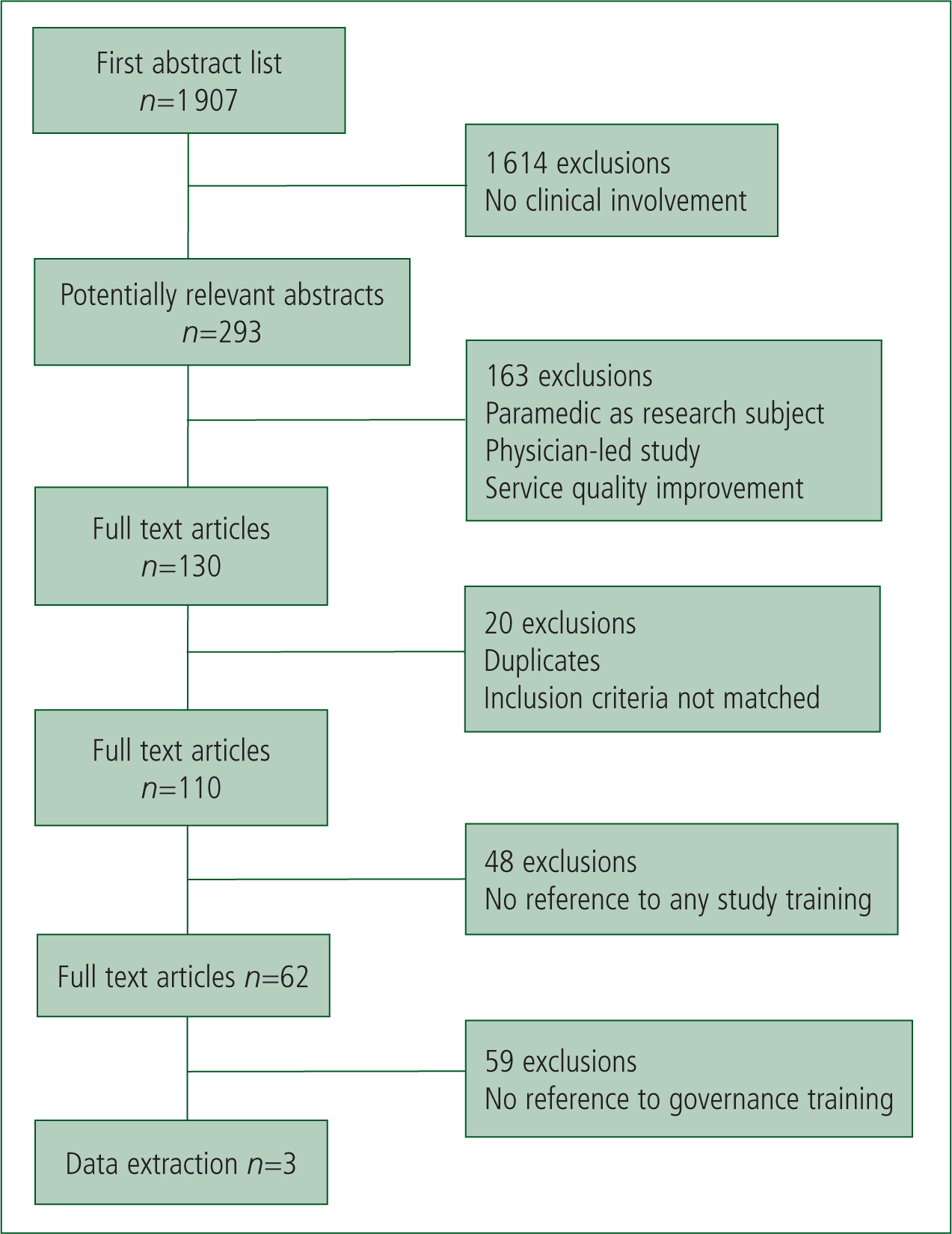

Searches were completed of both Medline and EMBASE electronic databases using a strategy reflecting a combination of MeSH terms and keywords: Prehospital OR Pre-hospital OR out-of-hospital OR ambulance-based AND clinical research. Filters applied were: Human; English language and publication dates falling between 1 January 1994 and 6 November 2014. There was no restriction on the country of origin or study type. Hand-searching of reference lists and citation searching of studies which fulfilled eligibility criteria were also undertaken, along with a search of grey literature identified from Internet searches and contact with content experts (e.g. College of Paramedics (COP), National Ambulance Service Medical Directors (NASMeD), Paramedic Evidence-Based Education Project (PEEP)). A single researcher screened a total of 1 907 abstracts against the inclusion criteria. Only studies in pre-hospital emergency care delivered outside of a hospital environment and involving clinical personnel were retained. Figure 1 illustrates the full screening process according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) convention (Moher et al, 2009).

Of 293 abstracts matching the basic inclusion criteria, 163 were subsequently excluded because they did not directly involve patients, were physician led, focused on quality improvement rather than generation of new evidence, or were relevant only to aviation medicine. Full texts of the remaining 130 abstracts were screened by two researchers. Following the removal of duplicates (n=8) and full articles that clearly did not fit the criteria (n=12), 110 were examined for their relevance to study training. This was enhanced electronically using the following word search terms in manuscripts: ‘train’ (e.g. trained, training); ‘brief’ (e.g. briefing, briefed); ‘educat’ (e.g. education, educate); and ‘instruct’ (e.g. instruct, instruction). Some type of study training was described by 62 studies. This does not imply that training did not take place in the other 48 studies, but simply that it was not documented. Of the 62 studies identified as possibly relevant, 34 outlined only the training needed to provide an intervention and did not refer to wider protocol issues (e.g. consent processes) or research governance content. Although the remaining 28 articles described training that included one or more general aspects from the research protocol, only 3 made a specific reference to provision of research governance training, all using the term good clinical practice or its abbreviation GCP (Table 1). The content was not available but as described below, the materials used to provide abbreviated GCP training to paramedics for the PIL-FAST study were used as the basis for the consensus exercise (Shaw et al, 2013).

| Study | Reference to research governance training |

|---|---|

| Jost et al (2010) | Broad pre-trial training was conducted with a reminder of good clinical practice |

| Brooke Lerner et al (2011) | Training included good clinical practice guidelines |

| Shaw et al (2013) | The training day included good clinical practice training |

Survey

An online survey was conducted across ambulance trusts between January–March 2015 in order to determine NHS paramedics' experiences of clinical research training. Participants responded to advertisements hosted by all NHS Ambulance Trusts and the College of Paramedics. Thirty questions were split into six sections. The first section asked for a personal training history, including whether or not individuals had received certificated research governance training, while section six offered the opportunity for free comments about experiences of clinical research. Sections two to five asked identical questions relating to the nature, mode and effectiveness of training received in respect to studies of any new drug treatment, device, patient assessment or other intervention as specified by the respondent. Although the response rate was low (n=120) the results indicated that training to prepare paramedics for a role in clinical research was inconsistent. Table 2 illustrates that when training was provided it was predominantly classroom based, with limited support materials, e.g. printed leaflets. Across the different types of study, the proportion of respondents who felt fully prepared to assist with assessing the new intervention were 52% for a drug, 65% for a device and 69% for a new clinical assessment. Only one in eight respondents had received GCP training.

| Study type | Number assisting | Attended training | Mode of training | Felt prepared after training | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Classroom | Online | Literature | ||||

| Drug | 20 | 19 | 17 | 1 | 6 | 11 |

| Device | 33 | 31 | 31 | 1 | 10 | 20 |

| Assessment | 15 | 13 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 9 |

| Other | 14 | 10 | 9 | 1 | 5 | 8 |

Expert consensus exercise

In order to develop appropriate pre-hospital training materials a Delphi-style exercise was conducted. The Delphi technique, described by Linstone and Turoff (1975) as a structured group communication method, facilitates consensus without the need for group members to meet in person. By seeking independent views it also prevents groupthink (Janis, 1982), i.e. pressure to conform rather than deviate from the dominant opinion.

Panel members were identified following a presentation of the systematic literature review and online survey results at the National Ambulance Research Steering Group (NARSG) meeting in May 2015. They included ambulance Trust research leads, senior paramedics, university academics and GCP trainers. A formal invitation and explanation of the process was extended by email. Although three iterations or rounds of opinion are typical for a Delphi exercise (Hsu and Sandford 2007), this was reduced to two because of a high degree of agreement between panel members in this case.

Round one took place in early June 2015. The 17 panel members were invited to rate the content and format of 29 generic slides used during the training of paramedics to assist with the PIL-FAST trial (Shaw et al, 2013). This was a pre-hospital feasibility trial of lisinopril versus placebo to lower high blood pressure during suspected acute stroke, which required paramedics to identify suitable participants, seek consent, provide the intervention (sublingual lisinopril or matching placebo) and complete study documentation. The adapted slides, grouped into six distinct sections, described the clinical research process paying close attention to the underpinning regulations and standards. They highlighted the core principles of GCP (Box 1), including informed consent, additional circumstances relevant to research in the pre-hospital environment, safety reporting and the importance of clear documentation. Slides were cross-referenced with current GCP materials.

The panel was asked to rate each slide using a scale, where 1 indicated no training value for ambulance personnel and 5 indicated high value and must be included. Free text comments about each slide were also collected. Fourteen respondents rated slides with scores from 1 to 5 with 5 being the mode value, indicating that the material was generally of high training value. Written feedback did not suggest that other material should be included, but minor improvements were made to 25 slides. Round two took place in August 2015 following revision of the slide set. All 17 original participants were also asked to comment on 12 multiple choice questions (MCQs) and answers to assess learning. Feedback was obtained from 12 respondents leading to minor adjustments to 6 slides and 3 MCQs. The resulting slide set and MCQs are now hosted online and can be found at http://tinyurl.com/gcp4para or alternatively www.neas.nhs.uk/our-services/research-and-development/research-training. Upon successful completion of the test, learners can download a certificate for their CPD portfolio.

Discussion

Increasing EMS clinical research activity is recognised as a national priority (Department of Health, 2010), but pre-hospital barriers include time pressures, service demands and traditional professional boundaries (Myers et al, 2008; Burges Watson et al, 2012). Training will assist with the latter, but this is challenging for two main reasons. The first is shift-based service delivery, which makes scheduling conventional face-to-face training sessions difficult, especially across large geographical areas (Ankolekar et al, 2014). The second is traditional use of standard GCP materials, which do not take into account the nature of pre-hospital research roles and evolving study designs (National Institute for Health Research Clinical Research Network, 2013). To help overcome these, we aimed to create specific training materials for paramedics and other ambulance personnel that could be delivered face-to-face or electronically, facilitate refresher training and stimulate involvement in research (Wood, 2012). This also addresses the concern expressed in the PEEP report (Lovegrove and Davis, 2013) that education and training for paramedics lacks a standardised approach, and instead provides an opportunity to undertake research governance awareness training with consistent content.

The systematic review failed to identify a benchmark for pre-hospital research governance preparation. Training was generally understated but the importance of alternatives to face-to-face sessions (e.g. video materials) was noted (Ankolekar et al, 2014). As the survey of paramedics across England confirmed training inconsistencies, it was considered imperative to develop materials via consensus. The slide presentation used during preparations for the PIL-FAST trial (Shaw et al, 2013) contained a modified GCP approach for a paramedic-led pharmaceutical trial, and offered a reasonable starting point. Slides were modified twice by clinical and academic experts in pre-hospital research, in order to provide a contemporary description of research aims, design, roles, responsibilities, legislation, standards, informed consent, safety reporting and documentation. These headings overlap with GCP topics, but the content has been abbreviated and contextualised as appropriate.

Although GCP training is traditionally regarded as an essential prerequisite for CTIMPs (Clinical Trial of Investigational Medicinal Products) (Health Research Authority, 2015), research governance awareness training is desirable for all types of studies in the pre-hospital setting. This would increase confidence in the research process by sponsors, EMS personnel and the public. These stakeholders may also be encouraged that an assessment was developed alongside the materials, comprising 12 MCQs endorsed by the expert panel. By offering participants the opportunity to gain a certificate of completion to bolster individual CPD portfolios, we hope to encourage interest and to benchmark an initial standard that can be reviewed during the ongoing evolution of pre-hospital studies and their related governance requirements.

Limitations

The main limitations for our project were a relatively low response rate to the online survey, and the small number of articles identified during the systematic review. However, this also reflects the uncertainty surrounding this topic and a lack of standardisation. There was insufficient information and time to contact individual study authors to enquire whether their training materials did actually include principles of GCP or research governance in practice, but the expert consensus ensured that no obvious resource was overlooked.

Conclusions

Using a structured approach, we have developed training materials specifically to facilitate an understanding of research governance during pre-hospital care. It will still be necessary for some ambulance personnel, particularly those acting as principle investigators, to regularly complete formal GCP training, but there is now a flexible and accessible alternative that can be adapted for individual studies.