Ambulance clinicians are attempting to avoid inappropriate admissions to accident and emergency (A&E) departments in line with the Bradley Report (Department of Health (DH), 2005), but are hampered by the lack of effective 24-hour mental health (MH) cover and referral pathways to places of safety, although improvements are expected. Increased strategic collaboration between MH care providers and ambulance trusts will liberate opportunities to capitalize on any improvements as joint stakeholders.

The Suicide Risk Assessment score currently listed within ambulance guidelines (JRCALC, 2006) is a fairly blunt tool, with poor staff confidence and use, typically resulting in the patient attending A&E. On review, the research panel proposed the adoption of an evidence-based assessment form for ambulance clinicians to use when assessing and referring MH patients.

Clinical governance

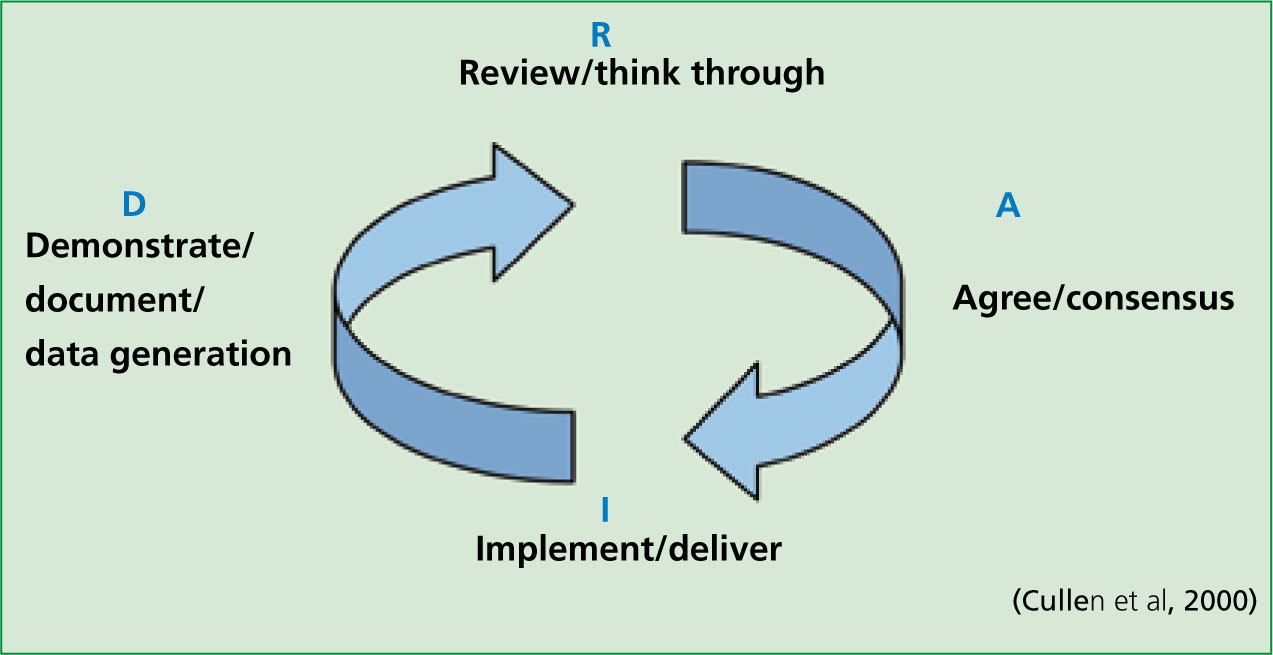

Scally and Donaldson (1998) advocate clinical governance to improve care and quality within the NHS. In line with this, this article will use the review, agree, implement and demonstrate (RAID) (Cullen et al, 2000) quality framework for this assignment (Figure 1). It has been specifically designed as a tool for clinical governance and is easy to use and understand. The process is split into four sections and encourages constant re-evaluation in the pursuit of excellence by its cyclic design.

For the purpose of this report, the review section will incorporate the rationale, literature review and ethics. The discussion will form the agreement section, and, as the result of this report, is a proposal. Its conclusion and recommendations will form the implementation phase. Further discussion and development will complete the cycle and feed into any additional initiatives resulting from the process, with tangible outcomes expected for the future.

Rationale for selection

This report was commissioned by the Strategic Health Authority, and they contracted with the higher education provider to accommodate a group of SWAST employees who had applied for the opportunity to research. The investigation and report are intended to feed back into the SWAST Service Development Strategy 2009–2014. This is designed to support the NHS South West's Strategic Framework for Improving Health in the South West 2008–2011 (2008) which, in turn, takes its lead from the White Paper Our Health, Our Care, Our Say, a new direction for community services (DH, 2006) which makes specific mention of MH service provision.

MH provision is not traditionally a clinical arena within which the emergency ambulance services have been associated, other than in the transportation of patients sectioned under the provisions of the Mental Health Act (1983). With the increase in prevalence and diagnosis of ill mental health, in conjunction with the moves towards care in the community and the introduction of the Mental Capacity Act (2005), ambulance clinicians are increasingly presented with patients requiring MH support. Provision of this support appears to have been outstripped by demand, especially out-of-hours, as patients now often dial 999 for help. Auditing such activity is currently too time-consuming if accurate data is to be obtained, as, unless sectioned under the provision of the Mental Health Act, patients potentially fall into several condition codes, which could also be used for patients without MH diagnoses (Table 1). A similar problem affects advanced medical priority dispatch system (AMPDS) codes.

| Category | Condition | Code | Comment on inclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory | Hyperventilation | M04 | Many patients are distressed and often present with anxiety. Would include genuine respiratory stress |

| Psychiatric | Section 136 (safety) | M30 | Sometimes used if police are on scene, even if not actually declared |

| Poisoning (accidental) | Alcohol | M46 | These could be used, particularly for CO poisoning, instead of deliberate self harm codes |

| Unspecified overdose | M49 | ||

| Gas/exhaust fumes | M50 | Would also include drunkenness and medication errors | |

| Other medical | Unspecified | M58 | A ‘catch all’ code for crews who cannot decide on which best applies |

| Could include many inappropriate cases | |||

| Trauma | Multiple codes | T01 to T16 | Crews could be drawn to serious wounds as most life-threatening and miss precipitating MH issue. |

| Inclusion would raise figures too high | |||

| Social | Social need (unspecified) | S03 | Often used for non-conveyed patients if condition not sufficiently serious or appropriate to convey |

| Inclusion would count non-injury falls, and patients not coping for reasons other than MH | |||

| Existing codes | |||

| Deliberate self-harm | Overdose, hanging and self harm | D01 to D07 | Ideally suited for purpose, but not always the condition that prompts the call or the most obvious element of the incident Excludes deliberate CO poisoning |

The original outline by SWAST was to review all MH issues. This initally raised concerns that the scope was too broad and this precluded sufficiently deep investigation. Preliminary meetings addressed this concern in part by splitting the group into two main teams and allowing individuals to focus on a specific area of study. The philosophical stance that this should not form part of an audit was also reinforced.

Although the topic was not every student's first choice, as clinicians, it was recognized how any initiatives resulting from the project could inform and improve practice. The author's own area of study was initially the wider picture—how do all other English ambulance trusts treat patients with MH problems presenting through the 999 system? Information was sourced from all ambulance trusts’ clinical or MH leads.

Once completed, it was agreed that some insight into decision-making would be useful, particularly if it could be turned into a tool for use by crews. This would be particularly useful in cases of deliberate self harm and threatened suicide, where patients present during the out-of-hours period—thus coinciding with the sparsest provision of specialist support services. These patients often present via the 999 system, and mainly to the ambulance service.

Literature review

Mental health has been predominantly governed by Acts of Parliament, although attitudes have mercifully altered from the original ethos. It is over 100 years since asylums were given the authority to detain ‘lunatics, idiots and persons of unsound mind’ by the Lunacy Act of 1890. Their powers were increased and their actions overseen by a Board of Control after the passing of the Mental Deficiency Act (1913). Wider legislation, in the form of the Mental Health Act (1959), sought to provide a legal framework for this detention, and to provide informal treatment to the majority of those persons suffering from mental disorders. This Act did not adequately clarify the legal empowerment of hospitals to treat MH patients against their wishes, but it was clear that this is necessary to balance the rights of the patient against those of the wider population. Although it appeared to take a long time, opinion and evidence collected throughout the 1970s informed the introduction of a completely new Mental Health Act (1983) to address and update all existing concerns.

The government White Paper Saving Lives: Our healthier nation (1999) targeted a reduction in suicide rates of over 20% by 2010, and fed into ‘12 points to a safer service’ which set standards to achieve this reduction—including rapid access to MH services for patients in crisis and the sharing of information with criminal justice agencies. The Royal College of Psychiatrists guidelines fed into the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) guidelines for deliberate self-harm in 2004, which laid down a framework for early triage and referral for specialist assessment (NICE, 2004).

More recently, the Mental Capacity Act of 2005 has introduced a legal framework for acting and making decisions on behalf of individuals who lack the capacity to make those decisions for themselves. The Mental Health Act (2007) amends previous legislation and specifically alters the provision of care in the community. Throughout this development, both academic and clinical opinion has informed and developed how these Acts are implemented on the ‘front line’. This report will concentrate solely on articles which inform its current debate. Current government guidelines insist on MH providers developing alternative pathways for known MH patients in order to avoid unnecessary police and A&E involvement, and have been funding these for some time.

Ethical considerations

It is imperative to consider ethical perspectives in the area of healthcare provision, as no one strategy is likely to suit every patient. It is important that the benefits of any intervention or initiative should outweigh any adverse factors, such as pain or distress. This principle of beneficence (Beauchamp and Childress, 2001) should ensure that the patients’ best interests are met and, although some MH patients sectioned under the Act may be subject to involuntary admission and treatment, the vast majority are not and remain important stakeholders in their own healthcare.

Gelling (1999) notes the importance of striking a healthy balance between protecting an individual and permitting him/her the freedom and independence to live a full life. Quality is again the watchword. The ideal outcome to a care plan is one which empowers not only the clinician, but also the patient, in a package that allows both to fully commit to their roles in working towards a mutually beneficial outcome. This could be complicated, or even compromized, if outside agencies are involved in crises, although good communication and sensible application of confidentiality should enable interagency cooperation and adherence to care plans with minimal disruption.

In the current climate, it is also crucial to consider the wider picture when focusing on an individual patient's needs and wishes—are there any dependants, such as children or elderly relatives, on whom any decisions regarding the patient would impact. Safeguarding is a fundamental part of any care plan, and not exclusively applicable to patients.

Discussion

With the Mental Health Foundation (2009) estimating the prevalence of mental ill health as affecting one in four people in the UK (Office for National Statistics (ONS), 2011), it is easy to see why this is an important national issue. Likewise, the incidence of adult self-harm is, at 400 cases per 100 000 people, the highest in Europe (Horrocks and House, 2002).

Somerset primary care trust stated that ‘GPs were treating more than 3 500 people for mental health issues and had diagnosed more than 2000 new cases of depression in 2007’ (BBC News, 2007). In consulting with all other English ambulance services, there is only one with a firmly established formal collaboration between mental health and 999 services—the Isle of Wight ambulance service, which is part of the Isle of Wight primary care trust. Unfortunately this is driven by and forged in geography rather than any pursuit of clinical excellence, as alluded to by the DH (2000a).

Government proposals from the DH (2000a) promote the integration of partner organizations to improve quality, safety and achievement of objectives, with a review of progress in 2004. Darzi (DH, 2007) also notes the role that ambulance services can play in streamlining healthcare delivery.

Auditing local incidence of self-harm, and particularly threatened suicide, is difficult via condition codes alone as often the patient presents with a complicated history, which may lead to an interpretive code from the clinician who treats the patient initially (Table 1). Merely culling this data would, perhaps, include some patients who share some clinical similarities with MH patients, but do not actually have a MH element to their current presentation, with the potential to skew the results in either direction.

Local provision of MH services mirrors Table 2 in that SWAST has several providers spread across its operational area, including Somerset Partnership (SP), and thus pan-trust policy is hard to imagine. SP is also managed in four broad areas: Taunton, South Somerset, Somerset Coast and Mendip. Any anticipated collaboration, therefore, would need to be brokered with all four areas and would ideally need to be agreed at county level, as a strategic alliance. As a backdrop to this, there is also concern that the anticipated 50% cut of inpatient MH beds available in the Mendip region will place an even heavier reliance on community services than is already acknowledged by SP (2006). Despite a recent press release declaring a collaboration between SP and the police, which should avoid patients subject to a section under the Mental Health Act (1983) being taken to an A&E department or police cell, there is no provision extended to those patients who present with a requirement that falls short of involuntary sectioning but who are needful of just such a provision.

| Ambulance trust | Formal pan-trust partnerships | Comments |

|---|---|---|

| East Midlands Ambulance Service | No | Ad hoc local arrangements |

| East of England Ambulance Service | No | Call advisors attempt to screen and refer to MH |

| Great Western Ambulance Services | No | Ad hoc local arrangements |

| Isle of Wight NHS PCT | Yes | As one PCT governs island so direct admissions possible. Crisis team out-of-hours |

| London Ambulance Service | No | Very varied. Many PCTs and boroughs. Some direct admissions. Some confidentiality blocking issues |

| North East Ambulance Service | No | Patients mainly go to A&E for assessment. Rare written care pathway already in place for direct admission |

| North West Ambulance Service | No | Some ad hoc arrangements. Mainly A&E admissions |

| South Central Ambulance Service | No | Some ad hoc arrangements. Mainly A&E admissions |

| South East Coast Ambulance Service | No | Call advisors attempt to screen and refer to MH |

| South Western Ambulance Service | No | Mainly A&E assessment. Rare crisis team intervention for known patients only |

| West Midlands Ambulance Service | No | Ad hoc local arrangements |

| Yorkshire Ambulance Service | No | Ad hoc local arrangements |

(The author notes that since the collation and completion of this report, some ambulance trusts have also conducted similar reviews, at least one of which has started to bear fruit in practice.)

These patients would normally contact the crisis team out-of-hours (20:30—09:00) or the home treatment team in hours, although they commonly dial 999 for a more expedient response. There is also a distinction made regarding patients not already known to S P, in that they will not be seen. This puts operational ambulance crews in a position where they are required to decide how serious or real a threat or injury is, and to decide on a course of action most appropriate for the presentation:

| System | Points for | Points against |

|---|---|---|

| TAG | Quick and easy | Document appears daunting (although front sheet only required for initial assessment) |

| Include social and vulnerability considerations | ||

| RAM | Easy to complete initially | Subsequent questions trickier |

| Onus on clinician to estimate severity | ||

| MHA | Similar to above Includes absconding risk | Again requires element of risk interpretation by front-line clinician |

| SRA | Very simple—takes seconds | Perhaps too blunt—outcome disproportionately weighted by some questions |

| RiO | Computer record | Not available offline |

| Good for confidentiality | No ambulance access | |

| No disclosure |

These scenarios are all governed by national and local guidelines; however, if the pathway is not obvious, the crew are engaging in an exercise in risk management.

‘Risk can be defined as an avoidable increase in the probability of an adverse outcome for a patient’

While many other clinical situations have tools to aid risk management within decision making (Ottawa Ankle Rules, thrombolysis, etc.), which have a root in evidence-based medicine, the operational paramedic is limited, in this instance, to the risk assessment tool in the JRCALC guidelines (2006). Any system used by health professionals should be aware of and try to avoid the issue of defensive practice (Harrison, 1997), which such a blunt instrument may engender as a side-effect. Allen (1997) also cautions any process which focuses too rigidly on actuarial indicators, such as gender, age and social standing, at the expense of a broader, holistic assessment. It was decided to explore other available tools in use by other organizations.

Threshold assessment grid (TAG) score

Devised following extensive research by Maudesley Hospital at its King's College site, this concentrated on a 1994 survey by a DH working group (Slade et al in DH, 1996) defining severe mental illness, which precipitated an investigation of the assessment of this severity. Several reviews have evaluated the qualitative impact of assessment and referral by this method with very positive results, culminating in a final report in 2006 (DH). The threshold assessment grid (TAG) system is also described in DH policy (2002).

The advantage of the TAG is that it requires only seven ticks on one form, making it a swift and simple assessment process. For each tick, a weighted score summarizes risk groups from ‘none’ to ‘very severe’ and suggests measures to be taken. A TAG score of greater than 4, or at least two scores of moderate risk, is suggested for best sensitivity while minimizing both false positives and negatives (Institute of Psychiatry, 2011).

Risk assessment matrix (RAM)

The risk asssessment matrix (RAM) was developed in 2004 at Royal United Hospital in Bath to allow A&E staff to rapidly and accurately assess MH patients at first presentation in the department; and has subsequently been positively reviewed (Patel et al, 2009). This assesses two key areas, ‘background history’ and ‘appearance and behaviour’, using a simple tick table with spaces for comment. Boxes are colour coded to guide the user to the degree of risk, which requires their interpretation of the risk category (low, medium or high) before suggestions for action.

Mental health assessment (MHA) form

Developed in collaboration between South West London and St Georges Mental Health Trust; Kingston University; St Georges Hospital Medical School, and Avon and Wiltshire Mental Health Partnership Trust in 2004. The mental health assessment (MHA) form was designed for use in A&E to initially assess patients presenting with MH issues. It considers the possibility of patients absconding from a department, but otherwise concentrates on appearance and behaviour. Questions are colour coded, as before, with clinician interpretation required for overall risk from low to very high. There is a separate section to determine risk of suicide, with more positive responses indicating increased risk. There are guidance notes for the next steps after assessment (these may also be known within departmental policies).

Suicide risk assessment (SRA) tool (SAD PERSON score)

A simple table of 11 responses with one point for each positive response. The threshold for medium risk is 3, but score one each for feelings of ‘isolation’ and ‘low mood’, so only one more is required from the remaining subjects (alcohol/drugs, <19 years of age > 45 years of age, previous Hx) to be guided to intervention. No guidelines to suggested referral pathways are included (JRCALC, 2006).

RiO electronic patient record (EPR) from Somerset Partnership

RiO is a product from CSE Healthcare Systems which provides ‘fully integrated patient administration, paperless clinical records and performance reporting functionality’. It is a fully web-based application developed using Microsoft NET technologies and supporting NHS standards, such as HL7 v3 and SNOMED CT. It has received plaudits from the Healthcare Commission (2005). The assessment section measures 14 different criteria from ‘no risk’ to ‘serious risk’, with a consideration of social factors involving dependants and vulnerable persons. There is, unfortunately, no paper element and is therefore not available for use by ambulance clinicians in primary care.

All systems appear to address the key points for initial assessment of mentally ill patients, such as the exclusion of external non-MH factors and their physical and mental presentation. Some (RAM, MHA) consider the ideation of harm to self or others, while others (TAG, RiO) consider the impact of the current episode on dependants or vulnerable adults (although most of the tools are designed to be used in A&E departments who may not consider this as an immediate priority).

The close correlation between questions and suggested actions hints at a common root in the Royal College of Psychiatrists and NHS recommendations (2004). For any system to be of use on ambulances, the process should perhaps consider capacity initially (DH, 2005) and then exclude other, potentially confusing, factors before assessing MH. A simple tick list would be preferable and more likely to encourage compliance, while also providing a clearly auditable trail linked to evidence based medicine.

Alcohol and mental health

The question ‘Have they consumed alcohol or drugs today?’ appears very early on many tools for MH assessment, and clinicians will be aware how soon it is asked when attempting to refer by telephone. Answering it affirmatively almost invariably results in a journey to A&E for the patient.

If the patient has been deemed to have capacity, is this strict adherence to history relevant, or could a more common-sense approach be explored? Patients who are evidently very drunk will not be appropriate for direct referral, as their compliance would be poor and they are likely to be disruptive; however, a patient who has taken a drink for ‘dutch courage’ before picking up the telephone and remains lucid, polite and compliant would surely benefit more from early referral, rather than spending the night ‘stewing’ until they are deemed sufficiently ‘sober’ to be assessed?

Although alcohol may modify behaviour, there are levels where it does not diminish cognitive ability (Miller, 2007) or motor function (the UK legal limit for driving is still 80 mg%) appreciably, and perhaps this could be woven into the decision-making process at an early stage.

Cost/beneft analysis

Cost-effectiveness is only one of a number of criteria that should be used to debate the introduction of any initiative (Phillips, 2006). With such an essentially qualitative issue, it is difficult to apply a hard cost to any element and to compare these adequately in pursuit of a definitive solution. From a business standpoint, the cost forecast would require a detailed audit of the frequency that MH patients could be referred directly to specialist services or places of safety locally, avoiding A&E, and offsetting this with the expense, both fiscally and on resources, of implementing a system to cope specifically with this scenario.

For the ambulance service, governed as it is by performance measured by response times, the most obvious saving to be made by securing a quick and streamlined referral process for MH patients is that of opportunity cost. This is defined in Collins English Dictionary as ‘the benefit that could have been gained from an alternative use of the same resource’. In this case, it would be the response to the next emergency, which could be seen as a productivity cost. Quantitative costs such as training time would be difficult to estimate, as many sessions would have the time spread over multiple students, and it is likely that these direct costs would be largely offset in the time saved at the roadside. Producing books of self-duplicating forms (similar to the ROLE and CR2 forms already in use by SWAST) would be negligible in the low quantity anticipated, and would benefit all by providing a ft for purpose, auditable record of referrals (Guly, 1996).

On the qualitative side, benefits would include paramedics further honing listening skills and engendering. As Horrocks and House (2002) suggested, an improved therapeutic relationship, which in turn would develop a better patient experience. Donebedian (1980) states that improving quality of care should be the driving force behind changes, a stance that most vocational clinicians would endorse. The costs associated with not improving services are termed ‘intangibles’ which make them hard to account for and are perhaps further from consideration if decisions are heavily influenced by fiscal policy.

Developing such a referral pathway would also encourage collaborative working patterns between MH service providers and ambulance service trusts. The current lack of this co-operation at the strategic level almost certainly hampers both parties’ abilities to achieve their core roles, and this in turn can tend to develop into an ‘us and them’ mentality operationally.

As of this financial year, there is a budget available to MH service providers to create links from the community to places of safety for MH patients to reduce the burden on the police and A&E departments. Many agencies are pointing to this money as an opportunity to remove themselves from the safety-netting of MH patients in the community in order that they focus on their core functions, although strategies are not universally in place to cope in this eventuality. This will surely only place the 999 system under greater pressure—now must be the time to be involved at the outset of change, to best ensure that robust plans are in place that do not rely overly on the ambulance service, and that pathways for MH patients are available on the occasions where this is unavoidable.

Conclusion and recommendations

Admissions to A&E due to mental ill health is on the increase, with MH service providers being encouraged to reduce the number of inpatient beds, which in turn increases the need for support services and access to MH professionals. Currently, there are already patients who find that they cannot source satisfactory help, particularly out-of-hours, and these patients are calling 999 in desperation. In order to best serve these patients and to reduce the impact of this on the ambulance services’ ability to fulfil their commitments to the wider community, the following conclusions and recommendations are proposed:

The key change would be to work in collaboration rather than opposition.