Pain is a common symptom associated with injury and illness, and is frequently the primary reason a patient will seek support or guidance from healthcare services. Despite the prevalence of pain, it is acknowledged that children's and adolescents’ pain is poorly assessed and managed (Friedland and Kulick, 1994; Hennes et al, 2005; Swor et al, 2005; Izsak et al, 2008; Brown et al, 2017; 2019).

Prehospital services’ encounters with children, including those of a traumatic nature, commonly involve paediatric patients in pain (Samuel et al, 2015). Despite this, evidence suggests that very few children in this setting receive adequate analgesia even though there is potential for skilled clinicians to deliver such care (Hennes et al, 2005; Swor et al, 2005; Shaw et al, 2015; Whitley and Bath-Hextall, 2017).

Considering the aim of all healthcare is to ease suffering and assist the patient to control their symptoms or disease to their identified or desired goals, it stands to reason that management of pain is a key concept within ethically sound care (Beauchamp and Childress, 2001).

There is, however, a lack of consensus between the various guidelines in the UK and internationally regarding the management of pain in those aged <16 years. For example, the Joint Royal Colleges Ambulance Liaison Committee (JRCALC) describes the approach but lacks specificity and tailored guidance across presentation (Brown et al, 2019). Guidance on choosing a specific analgesic for children is also absent in key published documents such as those by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2013; 2015).

While previous research has assessed the level of evidence about the safety and efficacy of pharmacological interventions in children (Samuel et al, 2015), there is a dearth of evidence exploring factors that influence clinicians’ decision-making in the assessment and treatment of out-of-hospital pain within a paediatric cohort. To date, only one small qualitative study carried out in Canada reporting emergency medical services (EMS) providers’ perspectives, barriers and enablers to paediatric analgesia has been published (Rahman et al, 2015). However, the authors acknowledge work by Whitley and Bath Hextall, 2017; Whitley, 2018; Whitley et al, 2019a; 2019b; 2021a; 2021b), which helped inform the context of this original research, and have subsequently published independent research that complements the current findings (Whitley et al, 2021a), as well as recent work by the current authors (Downs et al, 2022).

Such studies highlight the impact of adverse patient affect with ineffective treatment, and the lack of recording of non-pharmacological treatments and the impact of these on clinicians, patients and witnesses.

Aims

The aim of this study was to explore UK paramedics’ experience of treating paediatric patients in pain.

Materials and methods

Interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA), the method chosen for this study, can be described as a researcher ‘making sense of the participant, who is making sense of ‘x’ (Smith et al, 2009). Within the current study, ‘x’ is the clinical care of a child in pain.

IPA is said to be designed ‘bottom-up’, meaning that code is generated from the data, rather than using pre-existing theory to identify codes that might be applied to the data. This acknowledges that researchers may have different perspectives to participants and that this contributes to the value of analysis of the account, providing that there is shared thought; this means the researcher can look for meaning or influence that may not be directly articulated (Smith et al, 2009: Pietkiewicz and Smith, 2012; Tuffour, 2017).

While thematic analysis (TA) could also be considered for the analysis of interpretive and descriptive data, the authors felt that IPA held an idiopathic quality that TA lacked, when considering the identified niche profession. The emphasis on the detailed analysis of each account before consideration of the complete set within IPA may limit the overall generalisability of the themes identified by a researcher but may also permit themes to be challenged more robustly (Smith et al, 2009: Pietkiewicz and Smith, 2012).

By focusing on the insights of the individual, it can be argued that the reader may evaluate the extent to which others with similar context share perceptions, giving theoretical transferability (Smith et al, 2009; Pringle et al, 2011).

IPA has been critiqued due to studies being almost entirely descriptive with minimal interpretation; as such, it is recommended to restrict sample size and question numbers to facilitate more profound analysis (Giorgi, 2009; Hefferon and Gil-Rodriguez, 2011; Denscombe, 2014; Tuffour, 2017).

It is advocated that researchers endeavour to elicit rich and meaningful participant-researcher communication to enable meaningful phenomenological interpretation of collated data (Tuffour, 2017).

Giorgi (2010) accused the process of IPA of failing to translate phenomenology from philosophy to scientific method. McWilliam (2010) furthered this, concluding that phenomenology is the most subjective and confusing of all qualitative methodologies. This can be attributable to the absence of a prescribed method, and criteria for data analysis that may mean that emergent themes are those that the researcher has constructed from their predeterminations and opinions (Giorgi, 2009).

McWilliam (2010) concluded that we should laud the subjective nature of the participant-researcher relationship rather than critique it, They note that disputes over methods of qualitative research are dynamic, and if such produces analysis that is representative of the data and provides theoretical insights for the reader, with a clear explanation of their data analysis, then it is fit for purpose (Melia, 2010; Denzin and Lincoln, 2011).

Sampling

Recruitment comprised a social media drive (using Twitter, Instagram and Facebook), detailing the topic and the primary investigator and inviting eligible interested parties to take part in the research, providing a convenience sample.

The recruitment strategy resulted in a homogenous population. Eligibility criteria were: UK registration, a minimum of 2 years’ qualification and employment within an NHS ambulance service; these served to reduce the influence of preregistration education.

Adopting an IPA approach, where it is recognised that there is no fixed sample size or restriction, a sample of 6–10 participants was believed to be optimal (Pietkiewicz and Smith, 2012). This is a suitable size for the semi-structured nature, and scope, of the current project. Recruitment of 12 was feasible within the timeline, and exceeded the literature-recommended recruitment number.

IPA develops themes from individual narratives, and differs from other qualitative approaches in that patterns across the complete set of data are assessed at a later stage of the analytic process; this can result in ‘descriptive’ presentation (Rapley, 2011).

Ethical considerations

Informed, voluntary and continued consent was required from all participants (Griffiths, 2012; Denscombe, 2014). The participants were all given full information and consent forms at least 5 days before being interviewed, and were able to withdraw consent at any point up to pseudo-anonymisation of the transcript data.

All interviews were conducted via secure videoconferencing. Participants were advised that, if they became distressed, the researcher would suspend the interview before signposting to appropriate services and individuals.

NHS Research Ethics Committee approval (Health Research Authority, 2018) was not required to undertake this study. Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the University of Surrey (EGA ref 20-21 2017 FHMS).

Data collection

In total, 12 paramedics were interviewed for the study. Semistructured interviews were conducted between January 2021 and March 2021, via videoconferencing software because of COVID-19 social restrictions. Interview duration was within a range of 20–47 minutes. Data saturation was achieved, and no new themes appeared through comments, although this cannot be guaranteed during any qualitative exploration.

The topic guide, informed by the literature (Smith et al, 2009; Neubauer et al, 2019), focused upon past experience, notable encounters and individual knowledge. An initial pilot interview was undertaken to develop familiarity and confidence for the primary researcher. This was reviewed with supervisors and reflected upon to improve subsequent interviews and develop richness and depth of discussion.

Data analysis

Interviews were recorded using a secure device and transferred to a secure encrypted hard drive. Transcription was performed by the researcher and checked for clarity by supervisors (Adams, 2015). Subsequent IPA of transcripts was undertaken to analyse and process the data (Smith et al, 2009).

The primary researcher of this study was a practising paramedic which facilitated awareness, insight and the ability to interpret the meaning of data. Such a background does, though, have the potential for preconceived ideas and previous encounters to influence how meaning can be interpreted and, to counteract this, member checking and reflexivity methods were employed under the supervision of co-authors.

Results

Data were analysed to explore the stated experiences and feelings of UK paramedics and their attitudes to the provision and withholding of analgesia to children in the emergency setting, giving the phenomenological perspective of the identified cohort.

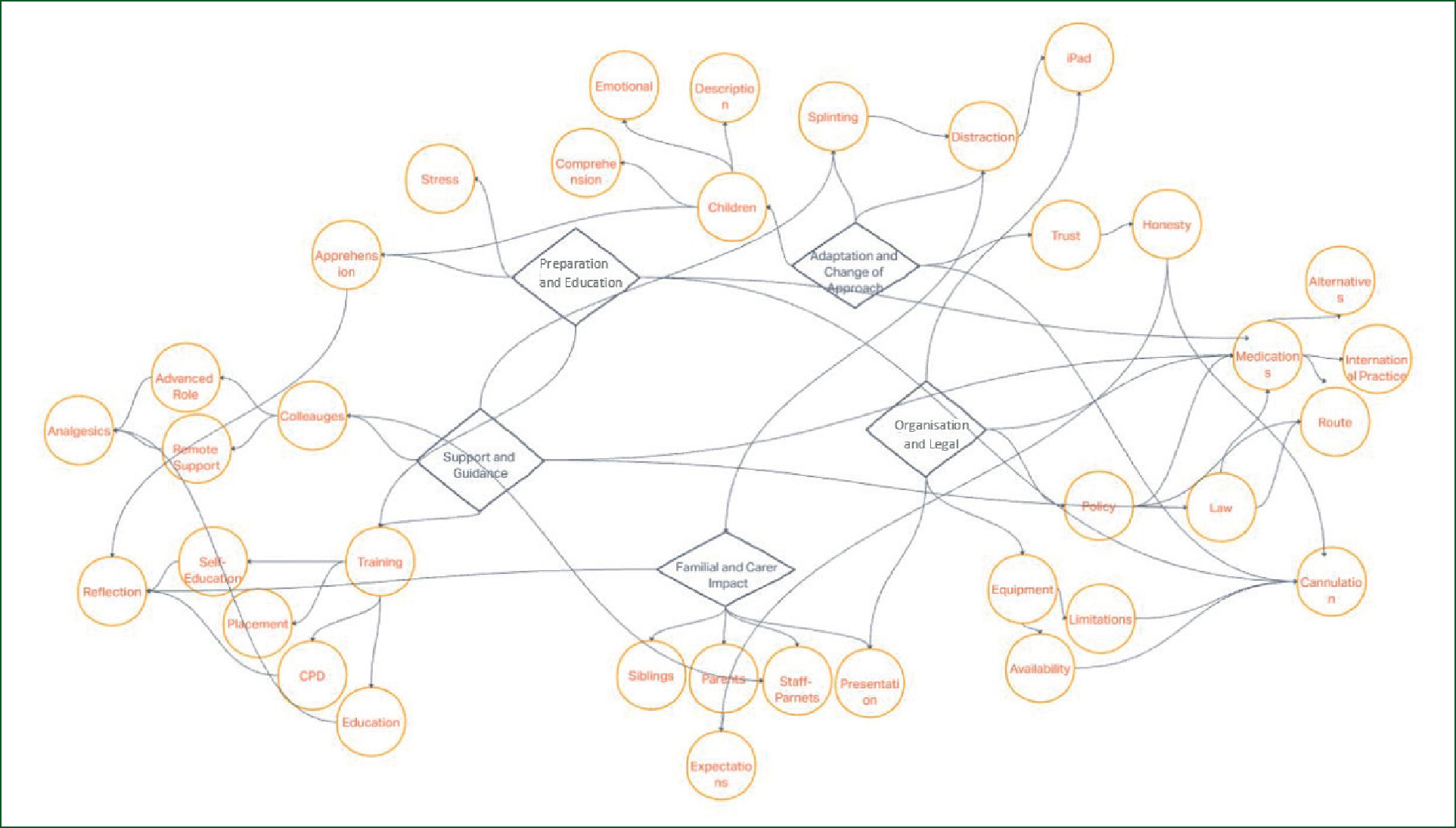

Five themes became apparent throughout analysis—preparation and education; adaptation and change of approach; organisational and legal factors; support and guidance; familial and carer impact—with some crossover between themes.

Of the 12 participants (Table 1), seven were women and five were men. The median (interquartile range) age was 28 years (25–33.5 years); the median (interquartile) length of professional experience was 5 years (2–5.4 years).

| Sex | Experience (years) | |

|---|---|---|

| P1 | Female | 6 |

| P2 | Male | 8 |

| P3 | Female | 7 |

| P4 | Female | 2 |

| P5 | Male | 3 |

| P6 | Female | 11 |

| P7 | Male | 2 |

| P8 | Female | 3 |

| P9 | Female | 2 |

| P10 | Female | 2 |

| P11 | Male | 4 |

| P12 | Male | 2 |

Theme 1. Preparation and education

All participants discussed the nature of education and preparation they had received with regards to the assessment and management of pain in children; the majority (8/12) felt that these had been suboptimal and that there was a lack of focus on this area of care.

Many felt this formed the root cause of any lack of confidence in treating children in pain; the anxiety that existed during their training never truly subsided as regular or continued training specifically on this was not provided and because of the generalist nature of the clinical role.

‘When I was at university, I don't think too much was done on paediatrics, and especially on their pain management. I think it was very much, “These are the drugs in JRCALC, use them".’ Participant 8

Numerous participants explained that techniques they found effective to assist children in pain were picked up from observing practice educators or hospital staff.

‘Just little tricks and paediatric-trained people just know how to calm children down.’ Participant 9

Continued professional development (CPD) and ongoing training were commented upon by six participants. The majority identified a lack of directed, ongoing education from employers and had to organise their own learning. It was felt this approach restricted the availability of education and opportunities to learn:

‘[Training should be] delivered by quality education by specialists in that field. [Those who] understand our job, not just what [we] do, they've got understand our job, they [hospital staff] often only see a packaged and calm patient presented, not the environment that preceded such.’ Participant 3

Theme 2. Adaptation and change of approach

Ten participants said they felt that gaining and maintaining children's trust was fundamental to their ability to care for and positively affect the treatment of the paediatric patients they encountered in pain.

Three participants said they needed to be explicitly honest with their paediatric patients regarding treatment and how they were going to care for them:

‘[I] think it is worth being honest to say, “This will pinch a little bit, but then we're going to give you something to get you comfortable” … If we're not honest and truthful with them, then I think that can have quite a lot of negative learning.’ Participant 11

Eleven participants said it was more challenging to treat pain in children than adults; the methods, skills and equipment used for adults were less practical because of the size and physiology of younger children.

Cannulation was almost unanimously discussed (11/12 participants) and was a point of apprehension and/or avoidance. Participants expressed reservations about the infliction of pain during the procedure and a lack of confidence in their likely success of obtaining access:

‘You don't want to miss [a cannula] in a child, whereas [in] an adult you don't want to miss anyway but it's a bit different because you can explain yourself… They look up to you, don't they? And, if you miss one thing, I know it's not the end of the world but putting a needle in a child is a big thing.’ Participant 9

All participants highlighted the need to change the approach they took in the assessment of paediatric patients in pain, acknowledging the comprehension of children differed depending on age. Participants said they altered the speed at which they undertook their management of children in pain when compared to adults, and also that care provided to children varied:

‘For a slightly older child, I might just try and simplify it a bit. If it's a four-year-old or that sort of age, then you can say, “Does it hurt anywhere? Is it really bad?” The Wong-Baker FACES as well, they are quite good. If they're a bit older than that, then you can say, “Mild, moderate, or severe?” Try and match that up to 0–10.’ Participant 10

All participants discussed the need or use of non-pharmacological methods of treatment and care for paediatric patients. Examples were given of distraction using bubbles or TV programmes and, specifically, methods of splinting and reassurance. Participants explained how they placed greater emphasis and effort into such methods with children, and that these were important because of the perceived inaccessibility of ‘usual’ methods.

Eleven participants described the use of distraction, and nine highlighted how the advent of electronic patient clinical records on tablets had meant they could employ these devices to use TV shows as means of distraction, with Peppa Pig and Paw Patrol specifically receiving a mention.

Three participants acknowledged the use of knowledge of such subject matter (or pop culture) as means to engage young patients, although one acknowledged that, as a child ages, this becomes of less use and that normal conversation is more appropriate.

Four participants highlighted the use of non-supplied aids to reward and engage with children, such as the use of blowing bubbles and stickers to reward and encourage children to permit assessment of illness and injury. Three explored breaking communication barriers with children, including animal glove puppets and the use of the blue trauma light within the ambulance rear to entertain children. Many said they preferred such methods of treating pain over invasive or pharmacological interventions:

‘Peppa Pig is as effective as morphine for a lot of pain. I'm super happy if they are just watching Peppa Pig on the iPad.’ Participant 6

Theme 3. Organisational and legal factors

All participants discussed and identified organisational barriers to their care. These were limited primarily to equipment and their perception of the purpose of their role, with feelings of being a stop-gap to definitive care or that trust policy dictated the need to take children under certain ages to hospital regardless of condition and, in cases of minor injury/ailment, that it was not their job to attend these.

Participants described how trust policy regarding the management of children affected care and treatment. The perception that a child would be conveyed regardless was perceived to change the attitude of clinicians and, as a result, less assessment and management would be undertaken:

‘Naturally, clinicians get a bit complacent and, in ones under the age [of] 1, they've got to go in anyway. Therefore, does that mean they're not assessing and managing and treating a patient appropriately just because they know they've got to go in anyway as per policy?’ Participant 3

The use of medicines was commented upon, with all acknowledging the medications they can currently administer in UK practice and that they felt these were not optimised for the treatment of children.

Participants felt that this disparity between paediatric and adult patients influenced how they approached treating pain in children. The use of oral suspensions was unanimously recognised; participants explained that they often found prior administration of such analgesics by parents somewhat disabling. When able to administer these, participants expressed frustration with issues of ensuring ingestion for optimal effect and the difficulty this presented when children were distressed:

‘They're trying to fight your way, they're trying to spit out the medication and just completely like against the idea.’ Participant 2

Participants felt that alternative routes would enable them to administer analgesia with greater ease and frequency. Three participants (P5, P6 and P11) discussed the legal restrictions surrounding this under UK law, which prohibits these practices for UK paramedics. The unavailability because of formulary restrictions caused frustration.

‘There's half of me that's going “You really should be giving something stronger.” There's half of me that's going “Don't do it. Don't do it. It's going to go wrong.” The jump is just too big, and morphine is just too scary. Something slightly higher up the scale but not morphine. Also, if the in-between step also doesn't require cannulation as well, that would be even better.’ Participant 10

Theme 4. Support and guidance

Discussion of the role of JRCALC in the assessment and management of paediatric pain was mixed. Participants expressed a variety of opinions on the value of the guidance provided in national guidelines (Brown et al, 2019), with some commenting on the simple easy-to-navigate guidance while others felt it was limited and added little value to their practice.

Specific comments were made about the explicit guidance for dosing of medication and how this reduced error and cognitive load (information that the individual is trying to process), but participants highlighted concern that these fixed doses also meant patients were frequently underdosed:

‘JRCALC generally doesn't have the best guidance in [Age per Page]. It's a bit of an ad-hoc weight calculation to work out the amount of morphine to give.’ Participant 11

‘And so, we've got the PGDs [patient group directives], really strict so can't deviate from them by the nature that they're PGDs.’ Participant 6

Six participants expressed how the input of colleagues in senior or specialised roles assisted their decision-making around pain management in terms of providing specialist care on scene or providing remote assistance to fact check ideas, considerations and treatment plans.

Furthermore, the provision of specific support desks within trusts appeared to be significant for participants, with the ability to lighten the cognitive load during potentially stressful situations. The ability to speak to senior colleagues and to ask about treatment options, the administration of drugs and the appropriateness of these was stated to reduce stress and aid decision-making.

Participants said that with greater exposure, if not an expanded scope of practice, they could bring more to patient care.

An awareness of the potential for alternative medications that are available to these teams also appeared to influence behaviour when presented with patients with potentially more significant injury, illness or pain:

‘I always call the critical care desk that we have in our area and tend to talk it through with them… they have a different scope of practice, but they don't have a different skillset for children, it's just someone who maybe sees sick kids more often than I do, but I think you have to weigh it up.’ Participant 8

Theme 5. Familial and carer impact

Aspects of trust and honesty have previously been discussed but 10 of the 12 participants also considered the impact of family and carers on their experiences of caring for children in pain. All discussed the impact of parental emotions on children, and the need to manage these carefully to manage the child successfully.

The explanation that children draw emotion and reaction from those they are familiar with meant that such reactions could be beneficial when managed well by clinicians or when the parent was calm:

‘As long as mum's calm, then the child tends to be calm unless they're at an inconsolable level. Mum and dad very much have a big bearing on what the child's going to feel like.’ Participant 10

Discussion

The current study shows that paramedics are aware of multimodal techniques for managing pain in children but are often less confident in the use of pharmacological than non-pharmacological management methods.

Advances in the use of technology in practices (such as electronic patient care records on tablet devices) have given clinicians alternative ways to engage with children and assist in the management of their pain. However, while using these methods, paramedics lack confidence that they are meeting social expectations of their roles.

The findings of this study are in line with recent research by Whitley et al (2021b) and Handyside et al (2021), reflecting growing concerns and the need to support paramedics in this area of practice.

Feelings of ill-preparedness

Paramedics held a universal desire to be able to care for paediatric patients to the best of their abilities; those with fewer years’ experience were more likely to express concerns about their ability to meet the needs of children in pain. Negative experiences and increased stress were associated with dealing with children in pain, and frequently attributed to a perceived lack of ability to adequately achieve the desired outcome.

Concerns were raised about the adequacy of preregistration education as well as subsequent CPD in trusts, which was reported to lack a paediatric focus and did not support participants’ development or confidence in treating children in pain. Rahman et al (2015) reported similar findings among more educated participants, who reported higher stress and lower confidence than those who held lower education qualifications and less scope of practice (Kruger and Dunning, 1999). This indicates that, while education is not the only contributory factor, the findings of the present study correlate with those of Murphy et al (2014), who found participants expressed their paediatric education as limited with a bias towards adults in education providers.

While educational drivers such as the Health and Care Professions Council (2017) and the College of Paramedics (2019) stipulate the need to consider healthcare across the lifespan, there is, given the epidemiology of illness, heavy weighting on disease and illness pathologies that present at older ages. The findings suggest that educational providers should review input for preregistration students to bridge this gap.

Non-pharmacological interventions

It was acknowledged that care could often be suboptimal. Participants identified that a lack of familiarity or ability to adequately assess and monitor pain in children prevented paramedics from treating it.

The absence of age-appropriate equipment has historically been acknowledged in the literature (Houston and Pearson, 2010), but does not appear to have been adequately addressed. Where services have acted on this, participants have perceived improvements in the care of children to be inconsistent and non-standardised, which highlights potential disparities in the provision of basic care to children (Roberts et al, 2005; Shaw et al, 2018).

Participants expressed the belief that in UK medicines legislation, permission and exemptions limited options to address pain in children. They discussed their desire for alternative means of administering medications, with suggestions of intranasal and per-rectum potentials.

This is supported by findings from other countries with similar EMS set-ups whose regulations permit other medicines and routes, which have been shown to increase the administration of analgesia to children and to reduce clinician aversion to attempts to manage pain (Bendall et al, 2011; Jennings et al, 2015; Whitley et al, 2021a; 2021b).

Whitley et al (2019a; 2019b) also found participants described organisational barriers regarding medicines included and routes of administration. Furthermore, they highlighted that facilitators to management included interaction with colleagues/others, exposure, being a parent and the use of technology.

Participants believed that familiar people influenced the management of paediatric patients experiencing pain in both positive and negative manners. The ability to use such persons to aid the management of the child, environment and the pain experience was frequently described, and is advocated by Brown et al (2019) as an effective provision for analgesia and scene control. It is further theorised that the reaction of the child is influenced, in part, by the reaction of those around them in ‘learned phenomenon’, and that the control of highly emotive reactions by familiar persons will assist in the management of pain (Melzack, 1965 and Wall; Whitley et al, 2019b).

Strengths and limitations

Sampling by invitation through social media enabled a wide audience to be invited in a short time frame and an accessible manner. However, this is likely to produce a sample that shares an interest in this subject, and restrict potential participants to those who are active on social media or people who are made aware (Flick, 2014).

This does not mean that the experiences of this sample are not important for analysis. Furthermore, the participant sample is taken from across a variety of UK ambulance services, reducing the potential of geographical bias (Denscombe, 2014).

Because of the small sample size, the findings may not represent the views and experiences of all paramedics but give insight into the experiences of those who took part and can be used to inform practice and future exploration of the care of children in the out-of-hospital setting. The participants may, however, have unconscious bias that could have influenced their responses.

Individual interviews were used to generate the data set and is limited in this respect; it is possible that the use of alternative or additional methods may have supported further credibility (Williams et al, 2012).

Because of the study's qualitative nature, the results are not considered generalisable to other populations or contexts. However, there is an element of conceptual generalisability and transferability.

Conclusion

The present study has highlighted that paramedics feel ill prepared for their role in managing children in pain. Despite this feeling, they have accrued skills and expertise within this area that permit them to effectively care for and manage these patients and situations.

To improve the level of confidence, a more robust approach to preparation is needed at the preregistration stage and throughout preceptorship and beyond; and ongoing education for pain management in children is required.

Alongside providing further psychological support, some potentially simple changes that trusts could make to further enable staff to feel more confident and reduce mitigating stressors for such encounters may include the following:

Further recommendations could include but are not be limited to: age-appropriate equipment; opportunities for CPD and bespoke training; and access to apps that can be used for distraction for children during care episodes.