Death by suicide among ambulance staff is rising and mental ill health symptoms are widespread (Mars et al, 2020). Increasing professional responsibilities, continual demand for emergency medical services and the COVID-19 pandemic have further increased the risk of mental ill health (Greenberg et al, 2020).

Ambulance staff across the globe provide emergency and urgent care, saving lives and managing medical crises. Frontline positions such as paramedic, emergency dispatch and call-taker personnel provide communication, coordinate response and manage direct patient care. An array of non-frontline roles including cleaning teams, mechanics and human resource personnel support the frontline response. Managerial teams provide frontline clinical aid.

Ambulance employees are regularly exposed to emergencies that could arouse intense distress, which may need to be suppressed to enable the delivery of patient care (Jonsson et al, 2003). Whether exposure is primary (face to face, as when a paramedic is on scene), vicarious (through an emergency call taken by the emergency call-taker) or secondary (managing the aftermath such as cleaning teams removing blood and matter from ambulances), detachment and dissociation are common coping mechanisms (Clompus and Albarran, 2016).

These can lead to later emotional consequences or immediate interference with functioning, which may result in mental ill health for some individuals (Austin et al, 2018). Evidence suggests that symptoms of mental ill health can negatively influence judgement, empathy and emotion regulation—factors key to prehospital care (Lawn et al, 2020).

It is therefore unsurprising that, in the UK, ambulance services report the highest rates of sickness absence among any NHS staff group (NHS Digital, 2022). Anxiety, stress, depression and other psychiatric illnesses are consistently the most reported reason for sickness absence. This consequently affects productivity and emergency service capability and can compromise patient outcomes (Maben et al, 2012).

Organisational support is a distinct construct that signals an organisation's commitment to employees and includes concepts of effort-reward expectancies, supervisor support, job satisfaction and procedural justice (Eisenberger et al, 1986; Ahmed et al, 2015). Research demonstrates that ambulance staff wellbeing is associated with access to organisational support (Gouweloos-Trines et al, 2017). Such support has been found to reduce the severity of symptoms, prevent suicide and enable staff experiencing mental ill health to continue to work (Milner et al, 2015).

The South Western Ambulance NHS Foundation Trust (SWASFT), one of the UK's largest ambulance trusts, developed a bespoke employee assistance programme, the Staying Well Service (SWS). This service embodies the concepts of organisational support by enabling all staff to ask for help and to be signposted to support services, such as counselling, when required.

However, staff perceptions of organisational support and avoidant coping may affect its uptake. Symptoms of avoidant coping include self-isolation, undue emotional restraint or trying not to think or talk about events (Penley et al, 2002).

Objectives

This study was designed to meet five objectives, the first of which was to investigate work-related stressful events and how they relate to staff characteristics, such as job role and gender, and avoidant symptoms.

The second was to investigate mental health sickness absence and whether the reasons for absence were disclosed to employers.

The third objective was to examine whether staff would use organisational mental health support and, if not, why not. Furthermore, the study investigated whether experiences of support were positive or not and how characteristics such as gender and unsocial hours (hours worked after 19:00 and before 07:00 and at weekends from Friday 19:00 to Monday 07:00) related to support utilisation and experiences.

The fourth objective was to investigate attitudes to employee support and any relationship to help-seeking, avoidant symptoms, age and gender.

Finally, the fifth objective was to assess employee perceptions of a mandatory time to talk session (time scheduled by the employer for staff to talk about and reflect upon work-related events) that could be offered at work to improve wellbeing.

Methods

Study design and setting

This voluntary, cross-sectional study used a survey of SWASFT employees. Because of the variability in the availability and quality of staff mental health support across UK ambulance organisations at the time, SWASFT was chosen as the setting for this study as the organisation had an employee population with access to a well-established mental health support service (SWS).

SWASFT operates 98 ambulance stations, three emergency number control centres (clinical hubs) and six air ambulance bases in south west England.

Patient and public involvement

A staff reference group worked with the authors to refine the research question, design the study and assist in interpreting and disseminating the results.

Participants

The survey was advertised once via Twitter and on SWASFT's closed Facebook group. No incentives were offered and all 4683 employees were sent the online survey invitation and participation information sheet via their work email address on 5 September 2018. Two follow-up emails were sent 7 and 21 days later. The survey remained open for eight weeks from 5 September 2018 to 31 October 2018 to maximise participation.

The power analysis for this study was based on Elhai et al's (2008) study investigating Attitudes Towards Seeking Professional Psychological Help. Elhai et al's (2008) study demonstrated a difference in attitudes about help-seeking between college students who had recently used mental health services and those who had not, with a medium effect (Cohen, 1988) (d=0.74). Setting power at 0.80 and alpha at 0.05 for a medium effect size suggested that a minimum of 60 participants would be required to investigate differences in perceptions between staff who have and have not used organisational support.

Participants gave informed consent, confirming that they understood the participation information sheet and met the eligibility criteria of being a SWASFT employee who had not taken part in the survey piloting. Staff consulted in the piloting of the survey before it was distributed were excluded from analyses to reduce familiarity bias.

Measures

Where validated scales did not exist, items were created with support from a staff reference group, and pilot tested with 24 staff and three expert advisers. Online Surveys was used to administer the survey (https://www.onlinesurveys.ac.uk). Adaptive logic led participants to answer between 17 and 40 fixed-answer and three free-text items.

Demographics

Seven items were included in the survey to assess gender, age, job role, part- or full-time status, working hours, geographical location and length of service.

Work-related stressful events

The impact of work-related events was measured with the Impact of Events Scale-Revised, Avoidance subscale (IES-R-A) (Weiss and Marmar, 1997). The full IES-R is a measure of symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) following a traumatic event. Since evidence suggests that avoidance is the most important factor associated with help-seeking (Kantor et al, 2017), the authors administered the IES-R-A only, which correlates highly with the other subscales (Beck et al, 2008).

If a participant answered ‘no’ to a single item asking whether a work-related stressful life event had been experienced (defined as ‘distinct experiences that disrupt an individual's usual activities, causing a substantial change and readjustment’ (Dohrenwend, 2006)), adaptive survey logic meant they skipped IES-A-R items. If they answered yes, the eight items of the IES-R-A assessing the degree of distress associated with symptoms of avoidance in the past 7 days were provided. Items were rated from ‘not at all’ (0) to ‘extremely’ (4) with higher scores indicating greater distress.

Participants were asked to complete the IES-R-A in relation to their most significant work-related stressful life event. They were also asked to indicate when the event happened on a 6-point scale reflecting time points from ‘within the last 3 months’ to ‘more than 20 years ago’ and to indicate if they had experienced one, two, three, four or five or more events in their time with the ambulance service.

The IES-R-A demonstrates good internal consistency (Cronbach's α range 0.74–0.87; test-retest reliability across a 6-month period in a range of 0.89–0.94) (Beck et al, 2008). The internal consistency found in this study was high (Cronbach's α=0.84).

Mental health sickness absence

Staff were asked about mental ill health sickness absence in the preceding 12 months as well as whether they disclosed the reason for the absence to their employer and if not, why not.

Perceptions and experiences of organisational mental health support

A 10-item questionnaire derived from Fischer and Turner's (1970) original scale assessed attitudes towards seeking professional psychological help (Fischer and Farina, 1995). A modified version of this scale, in which the Likert endpoint anchors refer to strongly disagree (0) and strongly agree (3) rather than ‘partly disagree’ and ‘partly agree’ was used. The shortened version correlates highly with the original scale (r=0.87), has been widely used and demonstrated good internal consistency in our sample (Cronbach's α=0.82).

Following pilot testing and feedback, outdated language of ‘mental breakdown’ was amended to contemporary terminology of ‘mental health crisis’. Since the perceptions of others’ willingness to seek help has previously been shown to influence one's own perceptions and behaviours related to help-seeking (Shakespeare-Finch and Daley, 2017), perceptions of colleagues’ willingness to seek help were assessed with a single additional item: ‘My colleagues would want to get psychological help if they were worried or upset for a long period of time’. Higher scores reflect positive attitudes towards help-seeking.

Staying Well Service feedback form

Since no validated scales were identified to assess experiences of organisational support, SWASFT's SWS feedback form (unpublished) was amended to include five items for this purpose.

Three of these items were positive (e.g. ‘Contacting the service had a positive effect on my mental health’) and two were negative (e.g. ‘I didn't feel supported by the Staying Well Service’).

Items were rated on a Likert scale from ‘strongly disagree’ (0) to ‘strongly agree’ (3). Negative items were reverse scored.

The scale demonstrated good internal consistency in this sample (Cronbach's α=0.78) Higher scores represent more positive SWS experiences (Appendix 1).

Acceptability of mandatory time to talk

A single item explored whether offering a mandatory time to talk session at work about work-related stressors would be acceptable to ambulance staff. Response options included ‘yes’, ‘no’ or ‘don't know’.

Statistical analysis

Data from completed survey responses were analysed with IBM-SPSS version 24. The only missing data related to optional demographics (7% of participants opted to skip). To protect against deductive disclosure, response groups of fewer than five were collapsed into a single category.

Total mean scores were tested for assumptions of normality with skewness and kurtosis values <1.96, eta-squared statistic's (η2) were calculated to indicate effect sizes and content analysis was used to categorise and quantify free-text responses. The following analyses were then performed specific to each objective.

Work-related stressful events: staff characteristics and impact

To investigate the association between work-related stressful events, job role and gender, chi-square (χ2) analyses were conducted. To investigate the impact of work-related stressful life events, independent sample t-tests were calculated to measure the differences in avoidant symptoms when the sample was divided into two groups that reflected whether staff had experienced mental health sickness absence, and then whether they would or would not contact the SWS for support.

A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted to compare avoidant symptom scores for groups reflecting the categories measured for the recency of the most significant work-related stressful event (six categories) and the frequency of work-related stressful life events (four categories).

Mental health sickness absence

To investigate mental health sickness absence, the percentage of staff who did and did not require such absence in the preceding year and whether or not the reasons for absence were disclosed to employers were calculated. Content analysis was then used to quantify and categorise the reasons for non-disclosure.

Experiences of employee mental health support

Independent sample t-tests were conducted to compare SWS total scores for groups, reflecting the categories for gender, unsocial hours, full- or part-time working, mental ill health sickness absence and whether staff would or would not contact the SWS for support.

Pearson r correlations were used to test the strength of relationship between avoidant symptoms and experiences of support.

Attitudes to mental health support and help-seeking

To investigate staff perceptions of employee mental health support and potential relationships to help-seeking, age and gender, ANOVA tests were conducted. These compared perception total scores for groups reflecting the categories measured for the following variables: willingness to contact SWS; age; and gender. Pearson product-moment correlations were calculated to assess the strength of relationships between perceptions and experiences of support as well as the relationship between avoidant symptoms and the perceptions of support.

Acceptability of mandatory time to talk at work

To investigate the association between the acceptability of mandatory time to talk and gender, mental health sickness absence, use of the SWS, length of service and job role, χ2 tests were conducted.

Findings

In total, 540 eligible ambulance staff completed the survey, an estimated response rate of 11.5%. There was an even gender split, and the majority of respondents worked full time (n=395; 73%) and unsocial hours (n=420; 77%). More than half worked in an ambulance (n=307; 57%), with the others working in an office or call centre. Over half were aged 31–50 years and all geographical locations with the ambulance trust's area were represented (Table 1).

| Demographic information summary table | ||

|---|---|---|

| Variable | Frequency (n=) | Per cent |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 255 | 47.2% |

| Male | 248 | 45.9% |

| Prefer not to say | 1 | 0.2% |

| Other, prefer to self-describe | 1 | 0.2% |

| Declined to complete the question | 35 | 6.5% |

| Age | ||

| 16–20 | 7 | 1.3% |

| 21–30 | 95 | 17.6% |

| 31–40 | 125 | 23.1% |

| 41–50 | 179 | 33.1% |

| 51 and over | 99 | 18.3% |

| Declined to complete question | 35 | 6.5% |

| Job role | ||

| *Frontline ambulance | 307 | 56.9% |

| **Clinical hub 999 or 111 | 84 | 15.6% |

| ***Support | 60 | 11.1% |

| ****Manager | 46 | 8.5% |

| Other | 7 | 1.3% |

| Declined to complete the question | 36 | 6.7% |

| *Frontline ambulance includes roles such as paramedic, ambulance technicians, emergency care assistants and specialist clinical roles such as air ambulance clinicians including ambulance doctors and hazard area response team staff (who respond to both usual 999 demand alongside any special category events such as multi-casualty incidents. **Clinical hubs are either 999 UK emergency call centres or 111 UK non-emergency medical advice call centres. ***Support roles include non-clinical roles such as human resources, finance, information technology, administration and cleaning teams. ****The majority of manager roles include frontline patient-facing clinical work. | ||

| Contracted hours | ||

| Full time | 395 | 73.1% |

| Part time | 91 | 16.9% |

| Bank | 19 | 3.5% |

| Declined to complete the question | 35 | 6.5% |

| Unsocial hours worked? | ||

| Yes | 420 | 77.8% |

| No | 82 | 15.2% |

| Declined to complete the question | 38 | 7.0% |

| % of unsocial hours regularly worked | ||

| 1–25% | 85 | 15.7% |

| 26–50% | 160 | 29.6% |

| 51–75% | 148 | 27.4% |

| 76–100% | 28 | 5.2% |

| Declined to complete the question | 119 | 22.0% |

| Length of service | ||

| Less than 1 year | 27 | 5.0% |

| 1–2 years | 40 | 7.4% |

| 3–5 years | 87 | 16.1% |

| 6–10 years | 93 | 17.2% |

| 11–15 years | 104 | 19.3% |

| 16–20 years | 83 | 15.4% |

| 21 + years | 67 | 12.4% |

| Declined to complete the question | 39 | 7.2% |

| Geographical location | ||

| Predominately rural area | 173 | 32.0% |

| Cornwall/Isles of Scilly | 44 | 8.1% |

| North and east Devon | 87 | 16.1% |

| Somerset | 42 | 7.8% |

| Predominately metropolitan area | 323 | 59.8% |

| Bristol North Somerset and South Gloucestershire | 114 | 21.1% |

| Dorset | 53 | 9.8% |

| Gloucestershire | 41 | 7.6% |

| South and west Devon | 59 | 10.9% |

| Wiltshire | 56 | 10.4% |

| Declined to complete the question | 44 | 8.1% |

Work-related stressful events: staff characteristics and Impact

The majority of participants reported experiencing a work-related stressful life event (n=444; 82%), with 53% (n=236) experiencing five or more events. A significant association between job role and work-related stressful life events was identified, (χ2(4)=38.44; P=0.001). Frontline ambulance staff (n=265; 86%) and managers (n=43; 93%) were more likely to report experiencing a work-related stressful life event than those in other roles, with managers most likely to experience repeated exposure (n=33; 76%). No significant association with gender was found (χ2(1)=0.81; P=0.36).

IES-R-A scores were significantly higher among staff who reported mental ill health sickness absence (mean=14.76, SD=7.06) compared with staff who did not (mean=11.58, SD=6.79; t(442)=4.16; P=0.001; η2=0.03), and for staff who would not contact the SWS for help (mean=13.84, SD=7.26) compared to those who would (mean=10.59, SD=6.52; t(264)=3.56; P=0.001; η2=0.03).

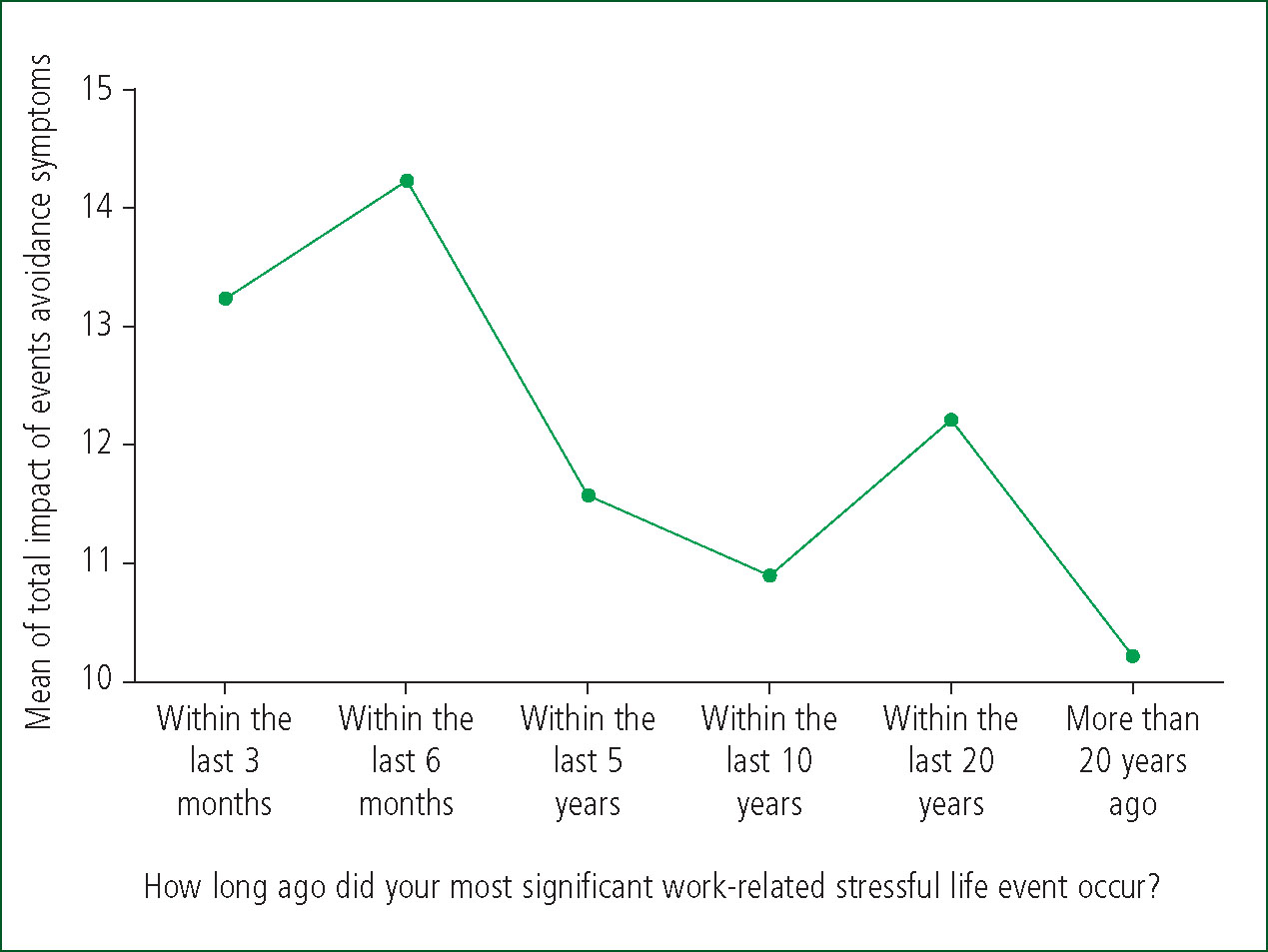

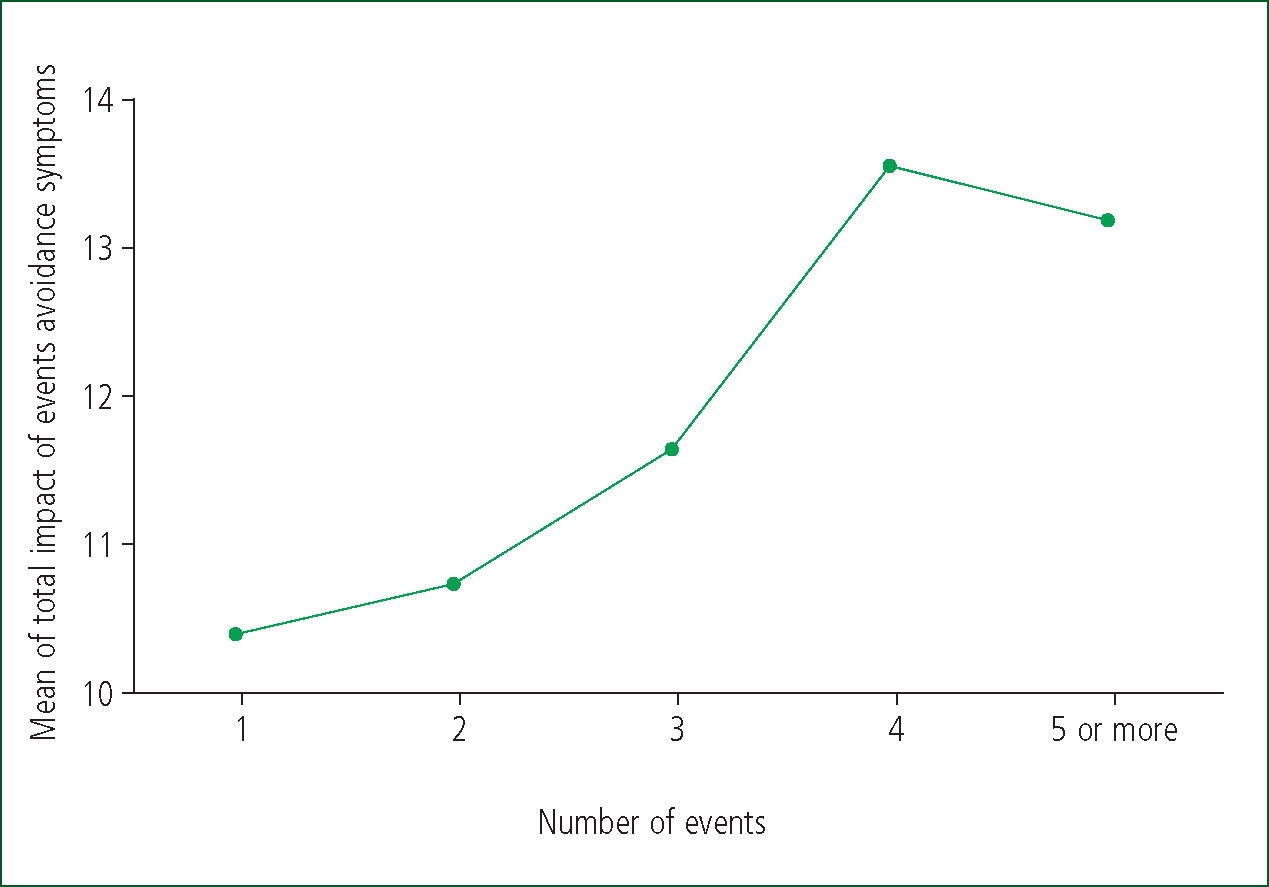

There was a statistically significant difference in impact-avoidance scores by recency of the most stressful life event (F(5, 438)=2.4; P=0.03) (Figure 1) and the number of events experienced (F(4, 439)=2.9; P=0.01) (Figure 2), although the difference in mean scores between the groups was small (η2=0.02).(Cohen, 1988), Posthoc Tukey Honest Significant Difference (HSD) tests indicated that IES-R-avoidance scores were significantly higher when stressful life events occurred ‘within the last 6 months’ (mean=14.24; SD=6.38), and ‘within the last 5-years’ (mean=11.57; SD=7.14).

Mental health sickness absences

One-fifth (n=117; 22%) reported mental health-related sickness absence in the preceding 12 months, of whom 35% (n=41) did not disclose the true reason for their absence to their managers.

Content analysis identified five themes: embarrassed/‘it will affect my career’; perceived lack of organisational support; stigma; initial physical symptoms resulted in mental ill health; and ‘I don't want to disclose’.

Experiences of employee mental health support

Most participants were aware of the SWS (n=503; 93%) and more than one-third (n=195; 36%) reported making contact for mental health support since its opening in 2015. Women were significantly more likely than men to report help-seeking from organisational support (χ2(1)=14.99; P<0.001) and the majority of staff reported positive experiences.

Independent t-tests revealed no significant differences between mean SWS experience scores and gender, unsocial hours, full- or part-time working, mental ill health sickness absence and whether staff would or would not contact the SWS for support.

Several participants commented on positive and, on occasion, life-saving experiences including: ‘Talking to Staying Well stopped me from dying by suicide’. Others remarked on how SWS use was hampered by inconsistent staffing, unsupportive management, stigma and previous poor experiences.

The majority of the remaining participants (n=345) who had not used SWS mental health support reported that they would contact the SWS if needed (n=249; 72%). The participants who would not reported that they would seek help from other sources such as friends, family, GP or blue-light charity services. Only four participants reported that they would seek help from informal organisational support (such as from peers).

No significant linear or curvilinear relationship was found between avoidant symptoms and experiences of organisational support (r(178)=–0.020; P<0.786).

Perceptions of employee mental health support

A significant difference in attitudes towards help-seeking was identified between participants who would contact the SWS for help (mean=19.50, SD=3.9) and those who would not (mean=14.80, SD=4.3; t(11.13); P=0.001). The magnitude of the difference in the means (mean difference=4.69; 95% CI [3.86–5.52]) was large (η2=0.18), suggesting that participants who reported positive attitudes to help-seeking were more likely to report willingness to contact the SWS.

Perceptions towards help-seeking were unrelated to age (F(5, 499)=0.596; P=0.70; η2=0.0005) or length of service (F(6, 494)=1.6; P=0.13; η2=0.01). However, men (mean=18.01; SD=4.45) and women (mean=18.88, SD=4.45 did significantly differ in their attitudes towards help-seeking, although the magnitude of the differences was very small (η2=0.009).

Participants perceived colleagues to be significantly less likely than themselves to seek professional help (t(540)=7.22; P=0.001; d=0.31). A medium strength positive correlation was identified between perceptions of help-seeking and experiences (r(195)=0.45; 95% CI [0.34–0.57; P<0.001), suggesting that positive perceptions of support were associated with positive experiences of it. The coefficient of determination (R2=0.20) indicated that 20% of the variance in experiences could be explained by perceptions.

There were no differences in the strength of this relationship between men (n=57; r=0.369) and women (n=103; r=0.402; z=–0.23; P=0.818). A weak yet significant relationship was identified between avoidant symptoms and perceptions of support (r(444)=–0.16; 95% CI [–0.26, –0.06]; P<0.001; (R2=0.02)) with more distressing avoidant symptoms being related to more negative perceptions of support.

Mandatory support

The majority (n=400; 74%) of participants agreed that introducing mandatory time to talk about the impact of work-related stressors would be acceptable, 14% (n=76) disagreed and 12% (n=64) did not know.

Mandatory support acceptability was higher among women than men (χ2(1)=7.87, P=0.005) and in staff who reported mental health-related sickness than those who did not (χ2(1)=10.8; P=0.001); acceptability was also high in staff who had not used the SWS, but would make contact for mental health support if needed χ2(1)=5.17; P=.023).

Job role significantly influenced the perceived acceptability of mandatory time to talk (χ2(4)=11.93; P=0.018) as did length of service (χ2(6)=18.40; P=0.005). Support staff (n=39; 65%), management (n=31; 67.4%) and staff who had worked for 11–15 years (n=65; 62.5%) reported lower acceptability than clinical hub staff (n=73; 86.9%), road staff (n=219; 71.3%) and staff who had worked for <1 year (n=25; 92.6%).

Discussion

This study focused on work-related stressful life events and the perceptions and experiences of organisational support among UK ambulance staff working for one English ambulance trust. Most participants reported having experienced a work-related stressful life event with associated avoidant symptoms that persisted for many years and became more distressing with cumulative events.

Positive perceptions towards organisational support were associated with whether staff would seek help for mental ill health if they needed to and with positive and even life-saving experiences when organisational support was used.

Undisclosed mental ill health sickness absence caused by embarrassment, fear and stigma was identified.

Overall, English NHS ambulance employee sickness rates of 9.4% appear to be higher than the NHS average of 5.4% and the UK general population overall sickness rate of 2.2% at the time of this study (NHS Digital, 2022; Office for National Statistics, 2022).

The reasons for mental ill health, sickness absence and reluctance to seek help among ambulance staff are complex, although increasing emergency call volume, responsibilities, exposure to traumatic events, both from a clinical perspective and those that result in moral injury, and ambulance culture are likely contributory factors.

Everyday challenges, such as complex procedures, autonomous decision-making, pressure to ‘see and treat’ rather than transport patients to hospital and unprecedented events, such as terrorism and COVID-19, increase the risk of physical, psychological and moral injury (Williamson et al, 2018).

In the present study, avoidant symptoms were significantly associated with mental ill health sickness absence and a reduced likelihood of help-seeking from organisational support services. Stigma, a leading cause of suicide, also prevented some of this study's population from help-seeking (Carpiniello and Pinna, 2017).

Ambulance culture combined with repeated exposure to stressful events may account for the widespread avoidant symptoms reported in this study (Lewis, 2018). Avoidant coping could be viewed as a form of self-preservation and Mikulincer and Shaver (2011) suggest that those with avoidant symptoms may view themselves as self-reliant and do not wish to rely on others to help them cope with life's demands. However, evidence suggests that emergency employee mental wellbeing outcomes improve if staff confront rather than avoid their reactions to stress (Arble and Arnetz, 2017).

Overall, participants reported positive perceptions towards help-seeking and perceptions were identified as the most significant factor in determining uptake of organisational support. According to organisational support theory (Eisenberger et al, 1986) staff perceptions about whether their employer cares about their wellbeing inform their general beliefs about the organisation. When employee socio-emotional needs are met and experiences of workplace support are positive, staff attitudes towards the organisation improve.

Conversely, regardless of whether avoidance of support is a coping mechanism, a symptom of PTSD or a function of being an ambulance service employee with cultural barriers to help-seeking requires further research.

Evidence suggests that emergency services, such as police and fire services, and staff in the wider healthcare system face similar risks of stressful event exposure alongside cultural and organisational barriers to mental health discourse and help-seeking (Quirk et al, 2018; Mind, 2019).

Accounts from health professionals arising from the coronavirus pandemic suggest their emotional support needs are high. Systems where employee perceptions and experiences of organisational support are not intrinsically enhanced may have profound ramifications for both employee outcomes and patient care.

Consistent with Karaffa and Tochkov's (2013) police study findings, participants perceived that their colleagues were less willing to seek support than themselves. This adds weight to evidence that cultural issues exist within this study's population. Current ambulance support systems place the burden on the individual to ask for help, and mandatory staff support removes this burden. Counsellors and some police and intelligence services have already integrated mandatory support into everyday practice and appear to find the practice useful for normalising mental health discourse and promoting help-seeking in the workplace (Ministry of Defence, 2017; College of Policing, 2018).

In the UK, a well-established ambulance service practice of allocating time for mandatory education days for patient care already exists. It may be helpful to apply this mandatory approach to staff wellbeing to ensure that staff are given space to talk and reflect upon their experiences. This approach may help to reduce the stigma associated with mental ill health and help-seeking and support staff to thrive at work, which could benefit patient care, especially in emergencies. Such an approach aligns with recommendations for ambulance staff wellbeing policy that interventions and education occur at individual, organisational and government levels (Lawn et al, 2020).

Key Points

CPD Reflection Questions

Strengths and limitations

This study was successful in capturing a snapshot of perceptions and experiences across a mobile, dispersed workforce. Its self-report, cross-sectional design prevents causal inferences from being drawn.

The relatively low response rate and confining the survey to one UK ambulance service may limit generalisability to other organisations with different cultures, diversity and support services. In hindsight, since only 7% of participants declined to complete the demographic questions, this section could have been made mandatory, although offering the option of a shorter survey for time-pressured staff was an important aim informed by pilot feedback.

Most participants reported experiencing work-related stressful life events, which could suggest a high incidence of event exposure in this population or may suggest that only those with lived experience of stressful life events participated in this study. This potential self-selection bias of respondents may skew the responses and therefore not be entirely reflective of the total population.

Finally, the only mental ill health issue addressed was the avoidance domain of PTSD and no formal psychiatric clinical diagnostic tools were administered.

Conclusion

This study provides a unique insight into the perceptions and experiences of staff mental health support in one English ambulance trust.

Positive perceptions towards help-seeking were reported, although stigma, fear and ambulance culture may prevent some staff from seeking help. Frontline ambulance staff and managers were more likely to report experiencing work-related stressful life events.

Women reported more positive perceptions of organisational support, were more likely to seek help and were more likely to find mandatory support acceptable than men. However, when support was used, the majority reported positive experiences, regardless of gender.

Mental ill health symptoms following work-related events may take many years to emerge, and result in sickness absence, something that not all staff are confident to disclose. It is therefore recommended that ambulance service organisations consider prioritising wellbeing programmes to improve perceptions through the normalisation of mental health discourse at work. This may help to improve staff experiences of mental health support when accessed.

Mandatory regular time to talk is a potential support service of value, which should be evaluated in future research to ensure this is a representative view of ambulance organisations and all ambulance service employees.