The following article is a case presentation of a patient encountered by the author whist working in the Emergency Department (ED). The patient presented with low back pain, and had been treated in primary care conservatively with analgesia. However during his assessment in ED he was found to have symptoms suggestive of Sepsis, and following further investigations an Ileopsoas Abscess (IPA) was discovered. A brief overview of the case if presented along with a discussion of the pathophysiology and management of IPA. Whilst IPA is a rare presentation, this case articulates the importance of red and yellow flags in the assessment of low back pain.

Case presentation

A 19 year old man attended an ED in Wales (UK) with an eleven day history of low back pain. Following a five mile walk he developed bilateral heaviness in his legs, one day later he experienced gradual onset of left sided low back pain radiating into his left buttock. He attended his GP who prescribed oral analgesia and diazepam. His pain increased in the following days, and he was advised to lie on the floor, which he did for the following three days. He later became unable to stand, and reported passing dark coloured offensive urine. The patient reported no saddle anaesthesia, incontinence, or paraesthesia.

Examination revealed: Pulse 112, temperature 37.5 º C, grade 4 power in left leg. Urine dipstick was +ve for blood, nitrites and protein 1+, otherwise it was unremarkable. Within an hour of this examination his temperature had risen to 39 º C. Initial management for sepsis included: Paracetamol 1g IV, oxygen, Augmentin 1.2 g intravenious (IV), Blood cultures, full blood count (FBC), urea and electrolytes (U&E’s), liver function tests (LFT), glucose, clotting, lactate, IV 0.9 % normal saline, CXR.

Outcome and follow up

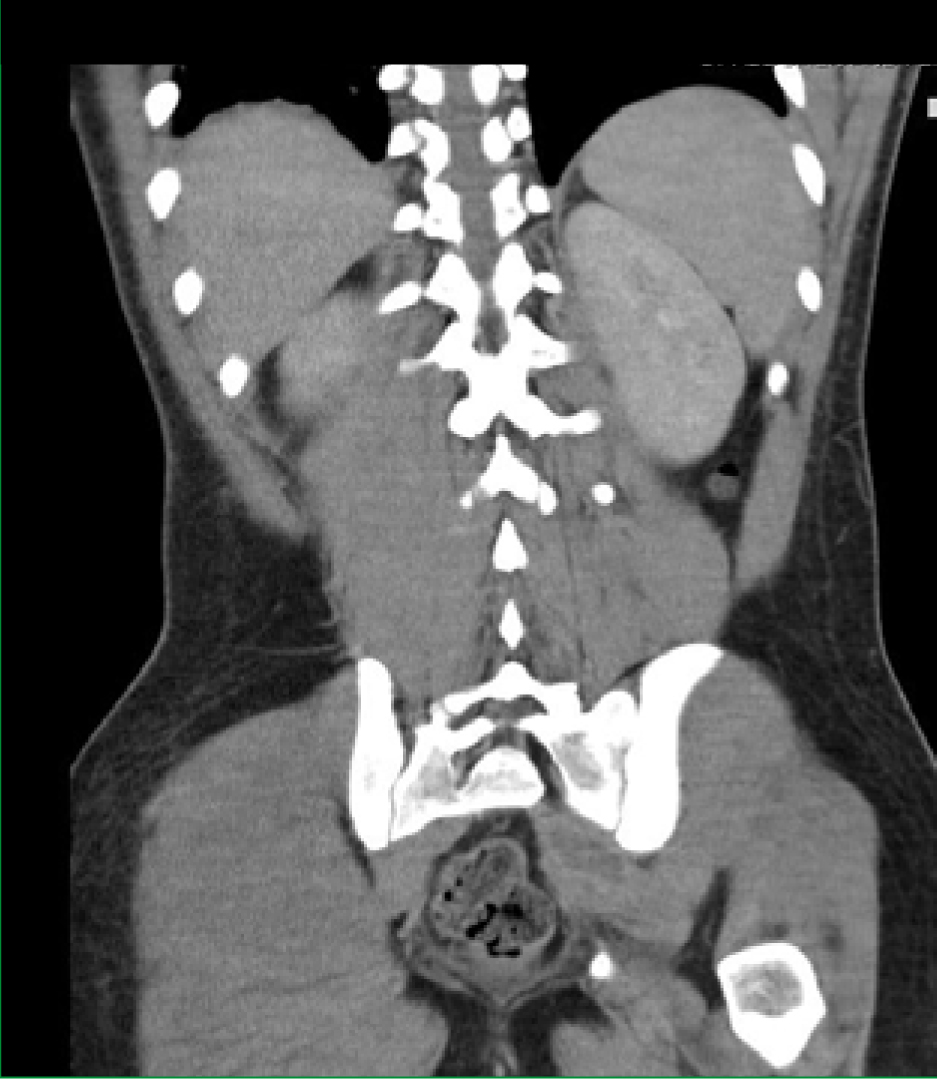

Computed tomogrphy (CT) pelvis and lumbar spine revealed a left ileopsoas abscess (Figure 1 and 2).

The result of the blood cultures found gram positive cocci, possibly staphalococcus.

Discussion

The first report of an acute inflammation of the psoas muscle in the literature was made by Mynter (1881) who described to the Buffalo Medical club a peculiar pyogenic abscess of the psoas muscle. An ileopsoas abscess (IPA) is a collection of pus in the psoas compartment, and, while the incidence has increased from an estimated 3.9 cases per year worldwide in 1986 (Ricci et al. 1986) to 12 cases annually in 1992 (Grunewald et al, 1992), the true incidence of IPA is unknown and probably underreported (Garner et al, 2006). Rather than a true increase in the incidence of IPA, the rise in cases is attributed to abscesses being diagnosed and reported more frequently by use of computed tomography (CT) scans to evaluate patients with unknown foci of sepsis (Taiwo 2001; Wael et al, 2008). The high mortality and morbidity in IPA is associated with its variable and nonspecific presentations, subsequently a misdiagnosis or delayed diagnosis is frequently made (Walsh, 1992). IPA can be primary or secondary; generally primary IPA are those that have no clear aetiology, while secondary IPA are a consequence of direct extension of infection from adjacent organs. Prior to improvements in hygiene and the advent of anti-tuberculosis (TB) drugs in the developed world, the commonest cause was by direct spread from spinal TB (Harrigan et al. 1995), however, reductions in TB in many parts of the world have affected both its epidemiology and aetiology (Walsh et al. 1992). Crohn’s disease is now said to be the most common cause of secondary psoas abscesses in the western world (Leu et al, 1986; Procaccino et al. 1991). In Asia and Africa approximately 99.5 % of psoas abscesses are primary, compared to 61 % in the US and Canada, and 19 % in Europe (Ricci et al. 1986)

Primary IPA:

Secondary IPA:

(Van Dellen, 1980; Spotkov, 1985; Gruenwald, 1992; Desandre et al. 1995; Orrison, 1997).

Anatomy

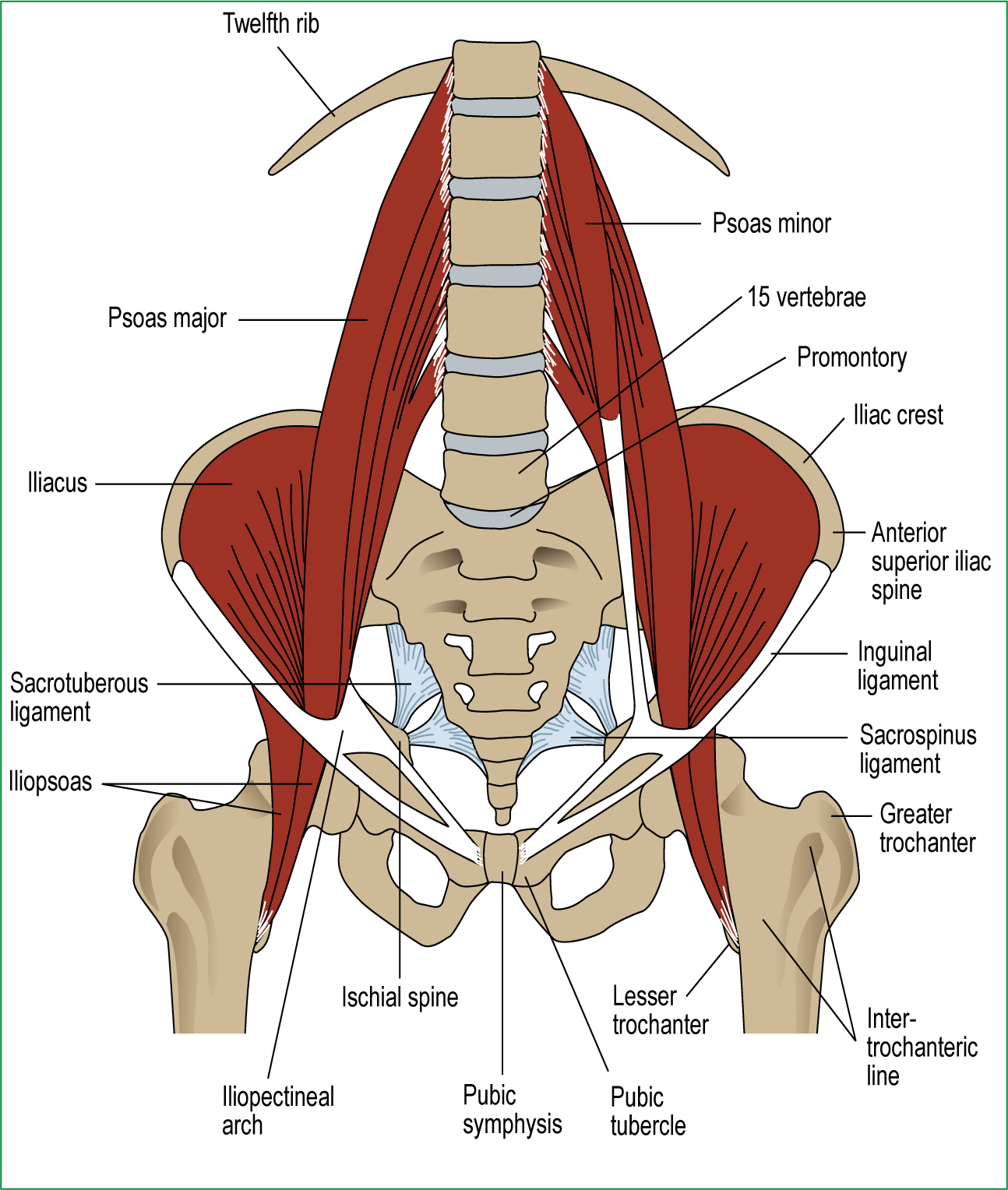

The clinical manifestations of the psoas abscess can be explained by understanding the anatomy. The psoas muscle lays retroperitoneal, close to the sigmoid colon, jejunum, appendix, ureters, iliac lymph nodes, abdominal aorta and the hip capsule (Figure 3).

Therefore, infections in these organs can spread to the iliopsoas muscle (Mallick et al. 2004). It originates from the lateral borders of the 12th thoracic to fifth lumbar vertebrae and ends as a tendon that inserts into the lesser trochanter (Cronin, 2008). It has a rich vascular supply that is believed to predispose it to hematogenous spread from sites of occult infection (Riyad et al. 2003)

Diagnosis

Mynter in 1881 described the ‘classic tria of fever, pain and limp in patients with IPA, despite this, such classic findings present in only 30 % of patients’ (Kao et al, 1998). The symptoms can be insidious and nonspecific, and while patients often present with a limp, fever, weight loss, and flank or abdominal pain, they are classically more comfortable lying supine with the leg slightly flexed and externally rotated, and the pain is often exacerbated by flexing the hip against resistance (Dala-Ali et al. 2010). Therefore, a good clinical examination is the key, followed by a CT scan to definitively identify the abscess and its possible aetiology.

Management

Until microbiology cultures of the abscess fluid hone in on the specific anti-microbial sensitivities broad spectrum antibiotics should be initially commenced. Percutaneous puncture or open drainage is then done followed by appropriate antibiotic therapy.

Back pain

Low back pain is the leading cause of activity limitation and work absence throughout much of the world (Lidgren 2003). It is both common and costly, in personal, healthcare and societal terms (Maniadakis and Gray, 2000; Van Tulder et al. 2002). It has significant socio-economic consequences, not only for patients and their families but also for the whole of the UK, with the most recent annual estimated associated costs reported to be five billion pounds (General Registrars Office, 2009). Despite low back pain being such a common condition, as in the present case; it can be the manifestation of more sinister pathology. With this in mind, guidance is available to support ones decision making (NICE, 2009) (Table 1).

| Red flags are possible indicators of serious spinal pat hology: | |

|

|

|

| Yellow flags are psychosocial factors shown to be ind icative of long term chronicity and disability: | |

|

|

|

When reflecting on the case, the patient presented with the red flags of under the age of twenty and fever, he also had the yellow flags of reduced activity levels, and an expectation that passive, rather than active, treatment will be beneficial. Such red and yellow flags should alert the practitioner to the possibility of a more serious under lying cause to the back pain, and guide subsequent actions.

Sepsis

The patient developed symptoms suggestive of sepsis, and while Ricci et al (1989) found that primary IPA rarely resulted in death (2.5 %), they noted in every case therapy was inadequate or delayed. Conversely, Ricci et al (1989) also found that secondary abscesses, carried a higher mortality regardless of the patient’s nation of origin (18.9 %), and sepsis was the primary cause of death. The causative organism is Staphylococcus aureus in over 88 % of patients with primary IPA, whereas secondary IPA is usually caused by enteric bacteria (Ricci et al, 1989). This was also found by Lopez et al (2009) along with abscesses of skeletal origin (35.2 %). In our case, staphylococcus aureus was the causative organism.

Conclusions

Low back pain commonly presents to practitioners, and the vast majority are benign, requiring conservative management. However, low back pain can be the manifestation of more sinister underlying pathology.

The present case turned out to be an IPA, which are a rare phenomenon. However, this case is an example of how an awareness of the red and yellow flags for back pains, along with the recognition and prompt management of sepsis is of greater importance in the emergency presentation than the final diagnosis. Nevertheless, if a practitioner suspects IPA prompt action is called for, as death from psoas abscess results from undue delay, and inadequate therapy. Management should include accurate diagnostics provided by CT scanning or ultrasonography, avoiding diagnostic delays, and a high index of suspicion must being maintained.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and any accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editor of this journal.