The Pre-hospital Emergency Medicine Crew Course (PHEMCC) is delivered by the Great North Air Ambulance Service (GNAAS) who are based in the North East of the UK. The course consists of three 1-week modules and is aimed at paramedics and doctors wishing to enhance their advanced pre-hospital care skills. This article will provide an overview of the paramedic author's experience undertaking the course, as well as the content, structure and delivery of each module. It will conclude with a doctor's and paramedic's perspective.

Background

Prior to joining GNAAS in April 2015, I had worked as an NHS paramedic for 9 years. This included several years on the road as both a rapid response paramedic and on the hazardous area response team (HART). In addition, I gained experience as a paramedic for the British Superbike and MotoGP medical teams at a number of race tracks around the country. After successfully applying to join GNAAS, I was enrolled on the PHEMCC as part of my induction training.

Before arriving on the PHEMCC, I had very little knowledge of what the crew course entailed. My preconceived ideas of the course content differed quite significantly from the actual programme. I expected that the main focus would be on providing critical care interventions and studying the evidence base behind them. Although practical training was indeed a key part of the course (particularly performing pre-hospital anaesthesia, thoracostomies, thoracotomies etc.), it was the emphasis on the non-technical aspects like crew resource management (CRM), communication skills, working in close partnership with a senior doctor and developing the interface with other emergency services that surprised me most.

A doctor/paramedic team working together in pre-hospital emergency medicine (PHEM) brings a unique skill mix to a critically-injured patient at the scene. There is increasing evidence to suggest that advanced interventions including pre-hospital anaesthesia, blood component therapy and advanced procedural skills, such as thoracotomy, bring an increased survival benefit to the sickest of patients at the roadside (The Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland (AAGBI), 2009; Chesters et al, 2013).

‘Before arriving on the PHEMCC, I had very little knowledge of what the crew course entailed. My preconceived ideas of the course content differed quite significantly from the actual programme’

Course structure

Having not known much about the course beforehand, I was surprised when I saw that it was split into several distinct components. The course directors explained that the PHEMCC has been derived from the original Helicopter Crew Course that GNAAS had provided to new operational staff since 2004. With the changes to training in pre-hospital emergency medicine, however, the course has evolved and adapted to provide opportunities for non-GNAAS applicants from across the UK. The course organisers intentionally aim for a 50:50 doctor/paramedic candidate ratio, meaning that the training and assessment scenarios ensure a similar skill mix to a normal operational crew. Personally, I thought this approach proved invaluable, as course candidates were able to bounce ideas and experience off each other; often doctors bringing hospital-based knowledge (for instance how to give a general anaesthetic) and the paramedics having a greater amount of experience with primary management of injury and working in the pre-hospital environment.

The course was divided into the following modules:

The final day of the course involved a real-time tactical exercise consisting of multiple casualties and several emergency services working together. This was followed by a high-fidelity scenario using a live casualty and moderated by external assessors.

Due to the complex nature of some of the advanced interventions being taught, the course placed significant emphasis upon the students in recognising the importance of having robust clinical governance structures in place. An example of this was the safe delivery of pre-hospital anaesthesia. The AAGBI highlight that ‘rapid sequence induction (RSI) or pre-hospital anaesthesia of a patient can only be performed by two suitably trained staff with a safe system of work in place’ (AAGBI, 2009). The course adopted these high standards and taught appropriate governance in accordance with the recommended guidelines, and strive to ensure that these standards were met by the candidates even as the complexity of training scenarios increased.

The course faculty was made up of a number of people from various backgrounds, all specialists in their area of expertise. The two course directors are consultants in anaesthesia and emergency medicine who have several years' experience as HEMS physicians in various systems, including the military. Other faculty included senior aircrew paramedics, hazardous area response team (HART) paramedics, pilots and experienced trainers from the fire and rescue service.

Module 1—Airmanship and Aviation Module

The crew course commenced with a week of aviation teaching and assessments. Coordinated by Multiflight at Leeds Bradford airport, the week began with 2 days of ground training. This covered the legal principles and framework for HEMS operations, crew competencies and familiarity with various aircraft types. This phase was followed by basic air navigation skills, meteorology and flight mechanics.

Upon successful completion of an exam covering the theoretical knowledge, the course took to the sky for practical navigation training. Each candidate took the front left-hand seat on a 60–90 minute flight around Yorkshire. Elements of this flight included planning routes, coping with last minute diversions, and gaining familiarity with using various paper and electronic navigation aids.

After completing the flying phase of week 1, arguably one of the most important subjects, crew resource management (CRM), was taught in some detail. CRM is a relatively new concept in the pre-hospital world but has been used in aviation for years. This approach identifies the importance of strong leadership, while encouraging individual team members to speak up in order to share critical information (LeSage et al, 2010). This culture is deeply embedded in modern day flight safety, but prior to this course I was unaware of it. However, this concept is now starting to filter into the medical profession to improve patient care and safety (Crosskerry and Cosby, 2009). Candidates' use of CRM then underpins the training and assessment scenarios for the remainder of the entire PHEMCC.

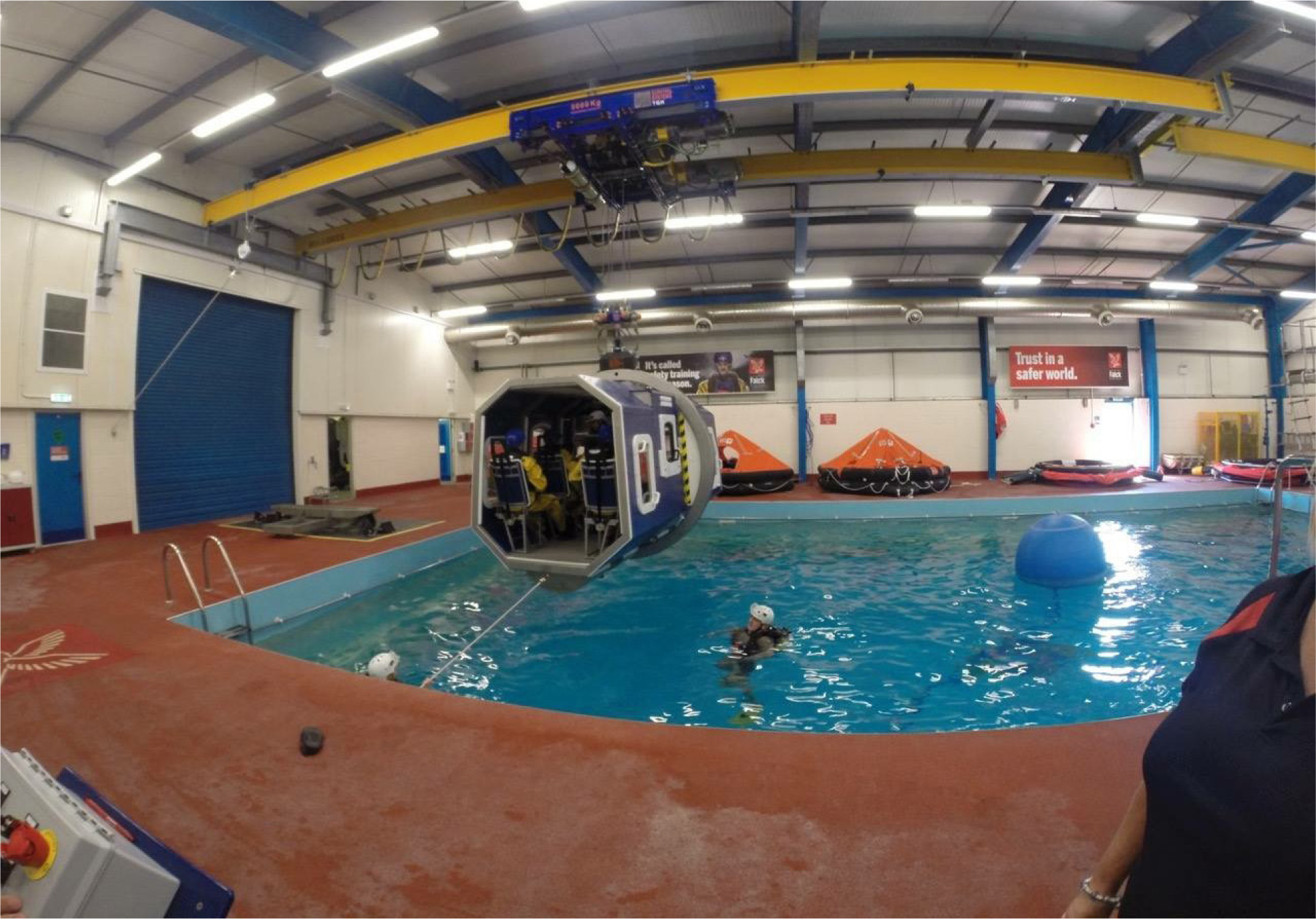

This first module finished on a high note with ‘aircrew underwater escape’ training. This involved being strapped into a simulated helicopter rig, being submerged in a cold swimming pool and flipped upside down. This was a pass or fail drill and you had to be able to remain calm and follow the procedure to escape. This was done four times, simulating various different scenarios, each one more difficult than the last. Following successful escape, the use of a life raft, life jackets and winching was practised, concluding the week.

Module 2—Clinical Week 1 (Clinical Skills)

The course continued with 2 weeks training in the clinical aspects of PHEM. This started with a tour of the highly acclaimed County Durham and Darlington Fire Service training centre at Bowburn. This was the first year that the course has been held at this purpose built facility, and as predicted, it proved ideal for PHEMCC training. It contains firehouses, dual carriageway areas, embankments, confined spaces, breathing apparatus training facilities and is expanding its remit at an exponential rate.

Day 1 consisted of pre-hospital anaesthesia (PHA) course refresher training. Pre-hospital anaesthesia was a large component of the course so an appropriate level of knowledge was essential. This is important from a paramedic perspective as my experience in this area prior to the course was minimal, and I would have struggled without completing the PHA course first. It is recognised that airway management in trauma patients is relatively poor (AAGBI, 2009), and it is highlighted that pre-hospital anaesthesia delivered effectively can improve this aspect of the patients' outcome. Although this course covers a number of topics, trauma management is a considerable part, therefore knowledge of associated drugs and procedures with regards to pre-hospital anaesthesia is paramount.

‘Although this course covers a number of topics, trauma management is a considerable part, therefore knowledge of associated drugs and procedures with regards to pre-hospital anaesthesia is paramount’

The second day took place at the Newcastle University medical school's anatomy lab. The day focused on catastrophic haemorrhage control, starting with the application of tourniquets, celox gauze and military bandages. This progressed on to thoracostomies and resuscitative thoracotomy, all practised on pig carcasses. This was fantastic ‘hands-on’ training, with additional advice given by the experienced faculty who had performed all of the procedures in a pre-hospital environment.

On days 3–5 the course returned to the Bowburn fire training centre where the focus was on ‘what can go wrong does go wrong’. The approach and management of children, the elderly, pregnancy, burns, CBRN and major incidents in the pre-hospital environment were all discussed and practised in progressively difficult cases. All of the training scenarios linked back to CRM and how candidates managed the scene using this philosophy.

Module 3—Clinical Week 2 (Multi-Agency Working)

There was a change of emphasis for the final week of the course. Although the clinical aspects still remained, the course started to develop our understanding of other agencies' capabilities and working practices. This began with a day's training around firearms and traffic operations with the police at the Police Tactical Training Centre in Urlay Nook. Candidates had the opportunity to handle firearms and to gain an appreciation of the tactical and medical implications of firearms incidents.

The following day the course returned to Bowburn, where the fire service delivered some exceptional training. The focus was on gaining an understanding of the capabilities and priorities of the fire service including stabilising vehicles, using cutting equipment and exploring A and B plans for the extrication of patients from road traffic collisions (RTCs). As paramedics this was not a new concept, however in reality, training in these scenarios is limited, with most paramedics doing it once or twice in initial training before being operational. I found the level and depth that the extrication session went into invaluable and not to be underestimated.

Further training was delivered both in terms of working at height and confined spaces, before we were given a ‘whistle-stop’ tour in the use of breathing apparatus (BA), prior to attempting the ‘BA shuffle’. This is a search technique used by fire fighters for locating casualties in a smoke filled room.

The course moved on to a firebox for demonstrations of fire and heat. The temperatures reached 400–500° and we were able to handle fire hoses and more importantly realise just how hot and dangerous fire fighting can be. These awareness modules were all run by either the fire service or the local HART team to give us an understanding and awareness of what each services' role is at an incident. It gave us an insight into what each part of the multidisciplinary team can bring to a case and where doctor/paramedic teams fit into the structure of an incident. As a former HART paramedic, it proved very interesting to look at incidents from a different perspective.

An invaluable learning experience was a ‘night scenario’ that involved multiple live casualties in an RTC. This simulated a car on its roof with multiple casualties and a motorcyclist in a ditch. Due to the added environmental constraints of low light conditions, this scenario tested our situational awareness, CRM and knowledge of the new critical care skills learned in an even more challenging situation.

The final day of the PHEMCC consisted of two parts: a large tactical exercise in the morning involving many fire appliances, police vehicles, ambulance staff and traffic officers, followed by a final assessment. The tactical exercise gave us the opportunity to participate in a 14-car RTC with multiple casualties. The exercise was incredibly good value, as it tested all of the skills we had gained throughout the week. In particular triage, decision-making, critical care skills, CRM and multi-disciplinary team working were all assessed by the faculty. The exercise was debriefed in detail with all of the multi-agency services and highlighted both positive and negative points. The final assessment consisted of a live casualty who had been involved in an RTC with multiple complex injuries. Upon completion, the candidates were individually debriefed on how they performed in the assessments and on the course overall.

Doctor's perspective

As a Royal Navy doctor with over 10 years' experience in various environments worldwide this course really did add so much to my knowledge base. All aspects of the course were excellent from start to finish. With the credibility of the instructors so high, it really was possible to learn so much from all of them.

It was not just the knowledge and technical skills that you gain from this course but I think the key aspects are the CRM and interagency awareness that run as the backbone to the course.

The course enables candidates from both doctor and paramedic backgrounds to work closely together and learn a great deal from each other. The size of the course (max 8-12 people) means everyone can get to know each other and then hopefully work operationally together on various PHEM systems.

I would recommend this course to anyone with even a passing interest in pre-hospital care, as the confidence you gain from having to push yourself cannot be underestimated.

Paramedic's perspective

As a paramedic with 10 years' experience ranging from double-manned ambulance crew and rapid response, to a member of the hazardous area response team, I have completed a number of different training courses, all of which have been invaluable in developing my practice. The PHEMCC is both the most challenging and also the most rewarding one. It is important to have a good base knowledge, in particular with regards to pre-hospital anaesthesia. Having already completed a PHA course I found I could concentrate on the other aspects of this course.

‘The opportunities to learn and improve as a paramedic were fantastic and I would recommend this course to all pre-hospital practitioners’

The lectures were all given by professionals with extensive knowledge in their area of expertise including GNAAS, police, fire and rescue and the ambulance service. This all added to the credibility of the course. Their enthusiasm and commitment to each of their specialties in the lectures made it very easy to listen to and learn from. There were a number of lectures but the majority of the course was practical, being continuously assessed over the course of the 3 weeks. Using the County Durham and Darlington Fire training facility allowed the scenarios to take place in actual pre-hospital environments. This included night exercises and a number of RTC scenarios working with other emergency services, thus in turn providing a realism that I had not encountered on a training course before.

The opportunities to learn and improve as a paramedic were fantastic and I would recommend this course to all pre-hospital practitioners, whether planning to work on a HEMS unit or not. The knowledge, skills and confidence taken from completing such a well organised course is invaluable.