Transient loss of consciousness (T-LOC) (also known as ‘blackouts’) is a loss of consciousness with complete recovery after the event (National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE), 2010). Sometimes there may be a prodromal period in which various symptoms (e.g. light headedness, nausea, sweating, weakness, and visual disturbances) warn that T-LOC is imminent. Often, however, the loss of consciousness occurs without warning (Task Force for the Diagnosis and Management of Syncope et al, 2009).

T-LOC is common, affecting up to 50% of the population at some point in their lives, and there are three major categories of causes: cardiac (which is the most common), neurological (such as epilepsy), and unknown aetiology. As such, T-LOC patients are seen by a multiplicity of health professionals, including ambulance clinicians (NICE, 2010). Lobban (2013) surmises that accurate and timely diagnosis following T-LOC is frequently not achieved and that not all of the potential causes of T-LOC are explored. Patients' symptoms are frequently ignored or dismissed as trivial. For patients, T-LOC can be confusing and cause anxiety or fear (Lobban, 2013), therefore it is also important from a non-clinical perspective that any potentially serious underlying causes are ruled out prior to discharge. Identification of patients most at risk should be possible with a detailed history and electrocardiogram (ECG) (Khoo et al, 2013). Ambulance clinicians can play a pivotal role in ensuring these patients are conveyed appropriately for diagnosis and management.

Background

In August 2010, NICE published guidance on the management of T-LOC in adults and young people. The NICE guidance aims to ensure T-LOC patients are directed along the appropriate pathway to receive the correct diagnosis as quickly as possible (NICE, 2010).

To help determine the cause of a patient's T-LOC, a thorough history and clinical examination should be undertaken and an ECG acquired. If it is unknown whether the patient actually experienced T-LOC, then T-LOC should be assumed until proven otherwise. NICE has an expectation that a 12-lead ECG post T-LOC is undertaken and that ambulance clinicians are competent in identifying a range of abnormalities (NICE, 2010). Historically, not all ambulance clinicians were routinely educated on the specifics of history taking, ECG pattern recognition, assessment and referral options specific to T-LOC. However, T-LOC is now included in paramedic training and some clinicians have completed higher education modules relating to T-LOC (e.g. cardiology or advanced ECG modules). Still, Thoburn (2013) questions whether paramedics are ready to adopt the NICE T-LOC guidelines.

If a capacitant patient declines hospital, NICE recommend they are referred to their general practitioner (GP) directly (NICE, 2010). It may be inappropriate to convey the patient to hospital if there is no evidence to raise clinical or social concerns, and a diagnosis of uncomplicated faint or situational syncope is made for the patient (due to strain on the autonomic nervous system provoked by: coughing, micturition, laughing and swallowing, for example) (NICE, 2010). However, the patient should still be directly referred to their GP and the justification for this decision clearly documented. In all other cases, T-LOC patients should be conveyed to hospital. The patient should be advised to take a copy of their clinical record and the ECG to their GP. If an ECG has not been recorded, NICE recommend the GP arranges an ECG within 3 days.

T-LOC can be reported to the ambulance service in many ways, therefore the frequency of T-LOC is currently unknown.

Aims

This clinical audit aimed to assess the compliance of ambulance clinicians against the NICE guidance on the management of patients with T-LOC.

Methodology

Setting

This clinical audit was undertaken in a large ambulance service in England that covers a geographical area of 1 580 km2 (610 m2) with a population of 8.2 million people. The service receives approximately 1.6 million calls annually, attending more than 1 million incidents (London Ambulance Service NHS Trust, 2014).

Patients' pre-hospital clinical records were retrospectively reviewed by a paramedic to assess compliance with NICE guidance on the management of patients with T-LOC (NICE, 2010).

An opportunist sample of 94 clinical records was collected over a 2-week period from the North East area of London. T-LOC coding was poorly used on the clinical records therefore any records with evidence of T-LOC were manually selected from other likely codes (no illness or injury, seizures (non epileptic), dizzy/near faint/loss of coordination, and collapse—reason unknown).

Where available, ECGs conducted on these patients were also reviewed. Data was entered onto an Excel spreadsheet and analysed using descriptive statistics.

Results

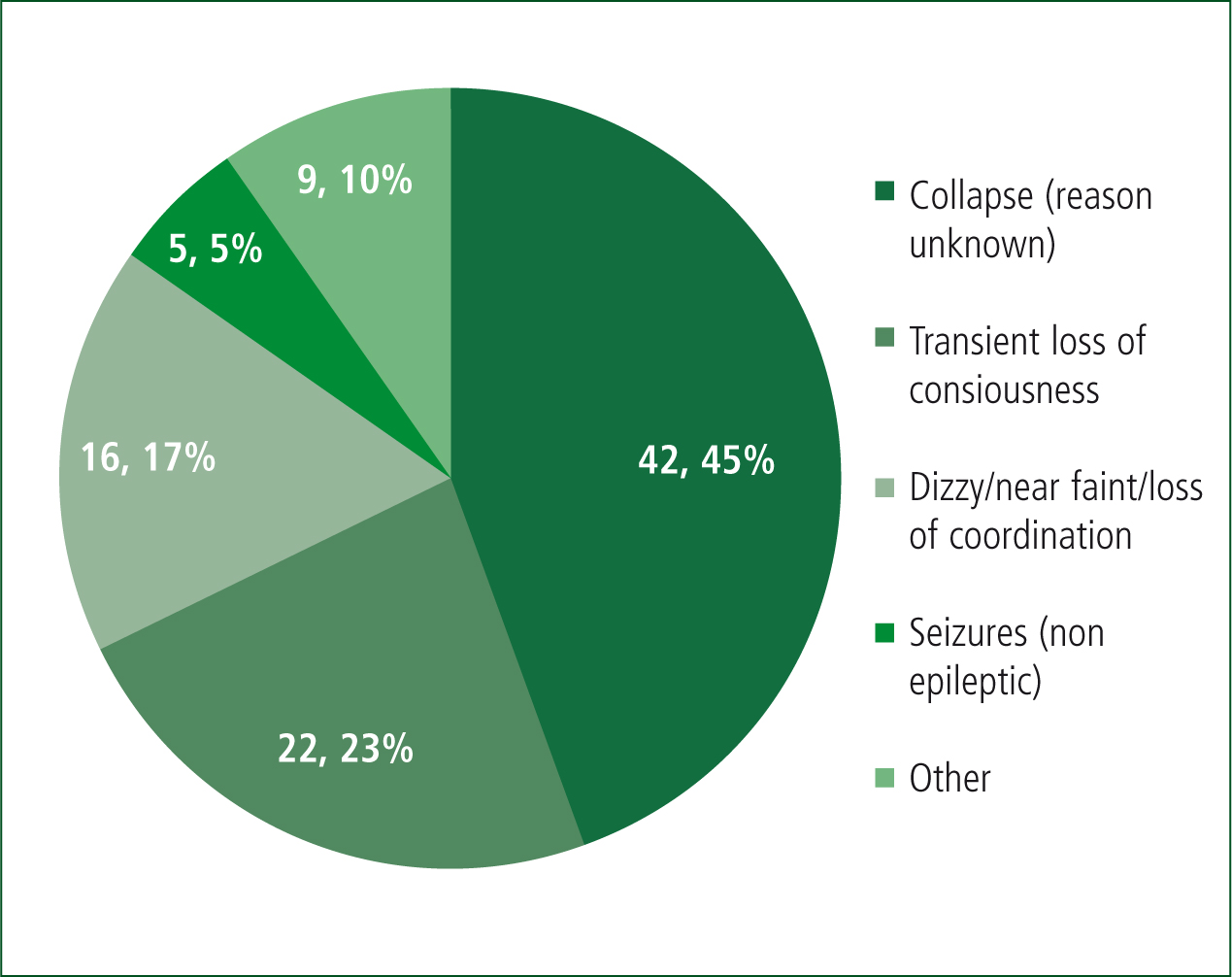

Patients most commonly presented as ‘collapse—reason unknown’ (n=42, 45%), and although ‘transient loss of consciousness’ was documented on every record, the T-LOC code was used on only 22 clinical records (23%) (Figure 1).

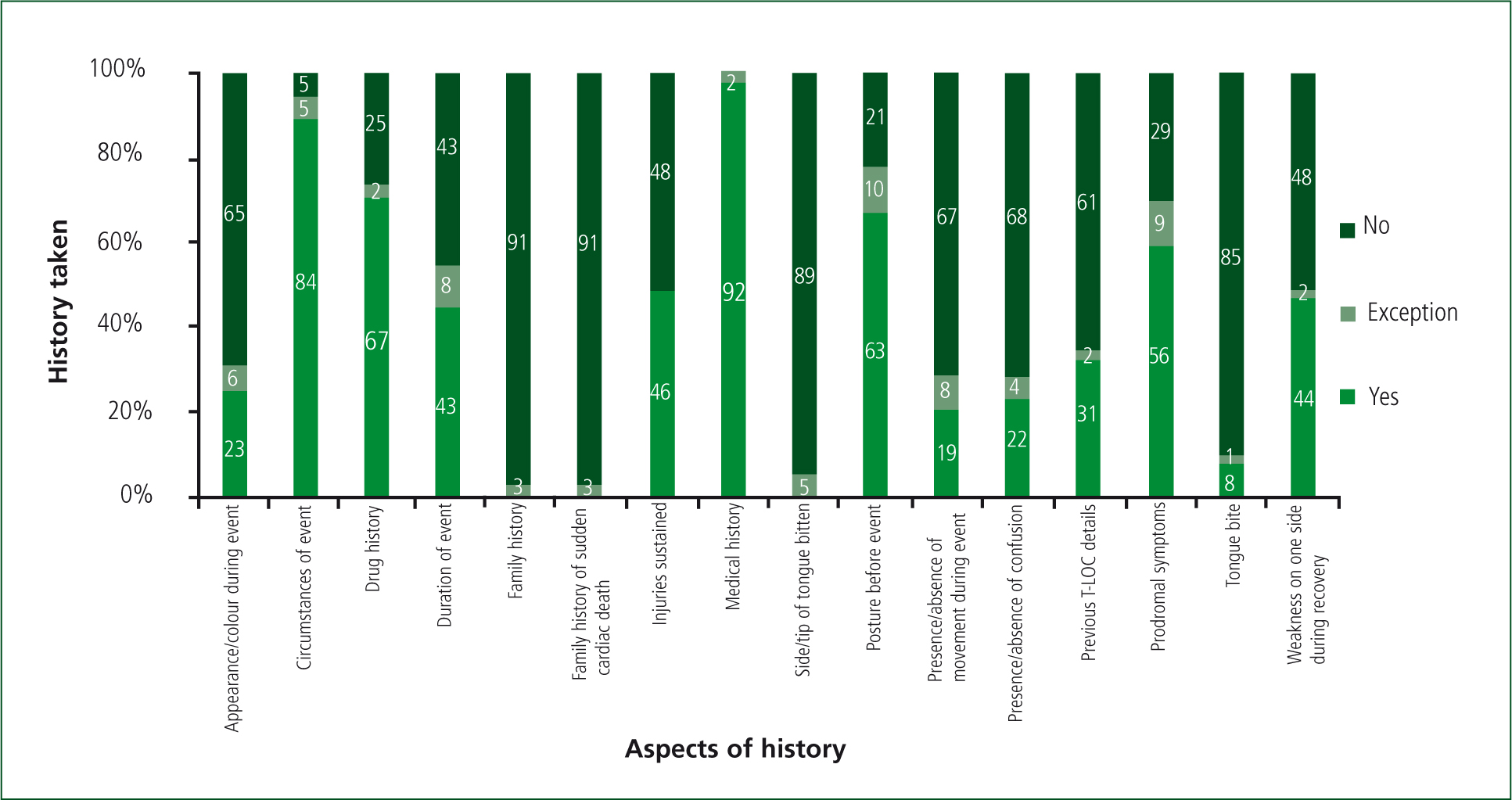

Medical history was recorded for every patient (100%, n=94) and history of the event for most (95%, n=89). However, more specific aspects of history which apply to T-LOC patients were not often asked. Ambulance clinicians did not ask about the patients' family history for any patients (including family history of sudden cardiac death) although three patients refused to communicate with the ambulance clinicians. Further information on history recorded is shown in Figure 2.

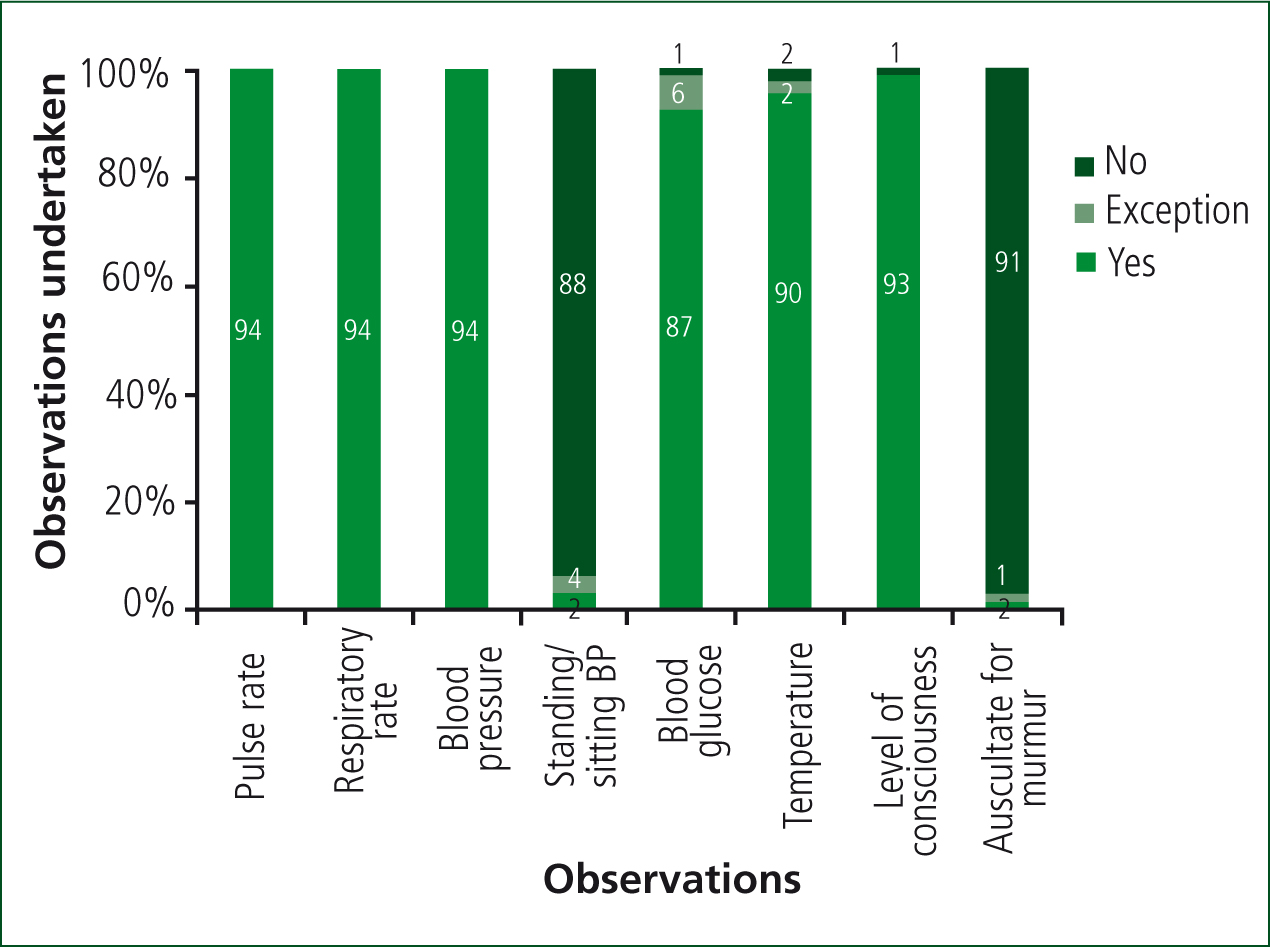

Clinical assessments that applied to all patients (pulse rate, respiratory rate, and blood pressure) were taken for all patients (100%, n=94). However, T-LOC specific observations were not undertaken for most patients: standing/sitting blood pressure (6%, n=6) and heart sounds auscultated (3%, n=3). Further information regarding assessments is shown in Figure 3.

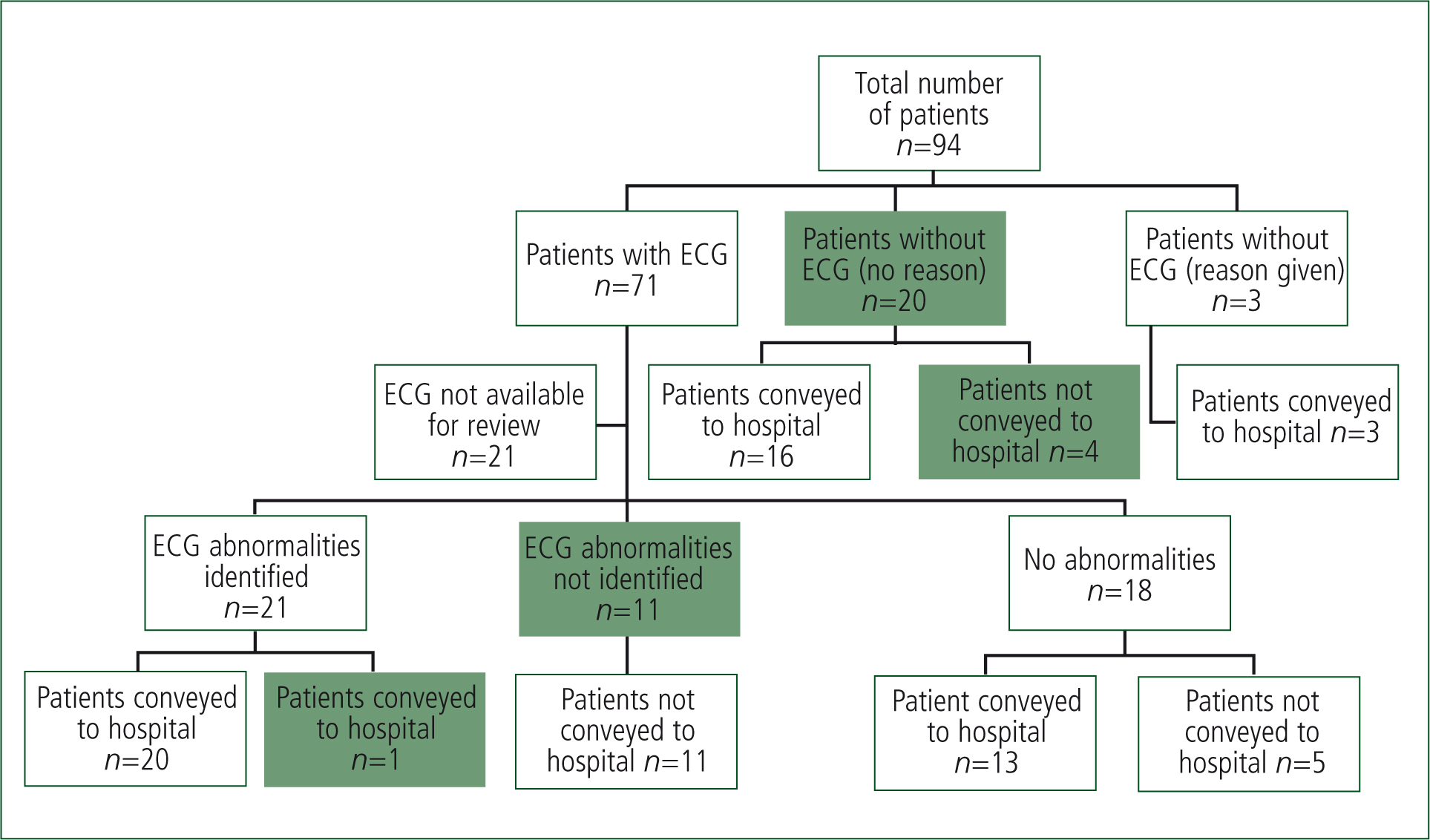

An ECG was done for 76% of patients (n=71), with an additional three patients for whom an ECG was not possible as they were either shaking too much or refused an ECG (all three patients were conveyed to hospital). The remaining 20 patients did not have an ECG, four of whom were left at home.

The ECGs were not available for review for 21 patients. For the remaining 50 patients, abnormalities were correctly identified for 21 patients, 20 of whom were appropriately conveyed to hospital. However, a further 11 patients had ECGs which showed abnormalities that were not identified by ambulance clinicians—all of these patients were conveyed to hospital. Details of the abnormalities identified/not identified are shown in Table 1. Eighteen patients (19%), for whom ECG was available to review, had no abnormalities and were documented as such (Figure 4).

| ECG abnormalities identified | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Bradycardia (HR <60) | 5 |

| Left bundle branch block* | 5 |

| Premature ventricular or atrial contractions | 4 |

| Long QT (QTc >460 mm/s) | 3 |

| Left ventricular hypertrophy (Sokolow-Lyon Criteria) | 3 |

| 1st degree atrioventricular block | 2 |

| Bi and trifasicular block | 2 |

| Right bundle branch block | 2 |

| Other T wave abnormalities | 2 |

| 2nd degree type 1 AV block | 1 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1 |

| Atrial flutter | 1 |

| Complete heart block | 1 |

| P-pulmonale | 1 |

| Sinus tachycardia | 1 |

| Left ventricular hypertrophy (Sokolow-Lyon criteria) | 4 |

| 1st degree atriventricular block | 3 |

| Bradycardia (HR <60) | 3 |

| Long QT (QTc >460 mm/s) | 2 |

| Left bundle branch block | 2 |

| Premature ventricular or atrial contractions | 2 |

| T-wave inversion | 1 |

| Right ventricular hypertrophy | 1 |

| Junctional rhythm | 1 |

87% of patients (n=82) were appropriately conveyed to hospital. The remaining 12 patients (13%) were left at home: 10 (83%) were advised to see their GP but without a direct referral, one patient received an appropriate direct referral to the GP, and one refused GP referral.

Discussion

This clinical audit showed that some elements of care given to all patients were consistently of a high standard; however, other elements specific to T-LOC need improvement. The more specific T-LOC elements that were undertaken rarely are vital for informing an initial clinical diagnosis and subsequent decision making. The risks to the patient of not having the full investigations are compounded, when in addition they have been left at home with no direct referral made to their GP. Many ‘red flags’ which aid diagnosis of T-LOC and determine the need for specialist attention are dependent on the findings of these specific features (NICE, 2010).

For T-LOC patients, ECGs are also important for enabling ambulance clinicians to distinguish between the uncomplicated faint and more serious underlying conditions. Therefore further areas of concern are the number of patients for whom an ECG was not taken, and the number of patients where it was taken but abnormalities indicated were not identified. Edwards (2012) warns of the lack of evidence of paramedics' ability to exclude ECG abnormalities to allow them to distinguish T-LOC from the uncomplicated faint. In this clinical audit, several abnormalities were not identified, including some long-term conditions (such as left ventricular hypertrophy and left bundle branch block) and conditions that are either common on normal ECGs or in isolation not a serious concern (such as 1st degree atrioventricular block, premature ventricular or atrial contractions and T-Wave inversion). Although these ECG abnormalities were not correctly identified on the paperwork, none of these conditions are dangerous and therefore it is unlikely these patients were put at risk.

If an ECG is not conducted, clinicians further limit their opportunity to identify any abnormalities that may aid the diagnosis of a cardiological cause for the T-LOC (NICE, 2010). A lack of ECG also means clinicians are not fully informed as to whether the patient is safe to be discharged at scene. The ECG is, for these patients, one of the best tools available to ambulance clinicians when deciding the next steps for the patient, and therefore by not taking the ECG and/or not recognising any abnormalities, this could prevent the patient getting the appropriate definitive care.

The majority of patients were conveyed to hospital, but when the patient was not conveyed, direct referral was rare and the reason for this is unclear. The benefits of a direct referral include a clear and seamless handover process and it allows concerns of the ambulance clinician to be raised directly to the GP.

Improvements

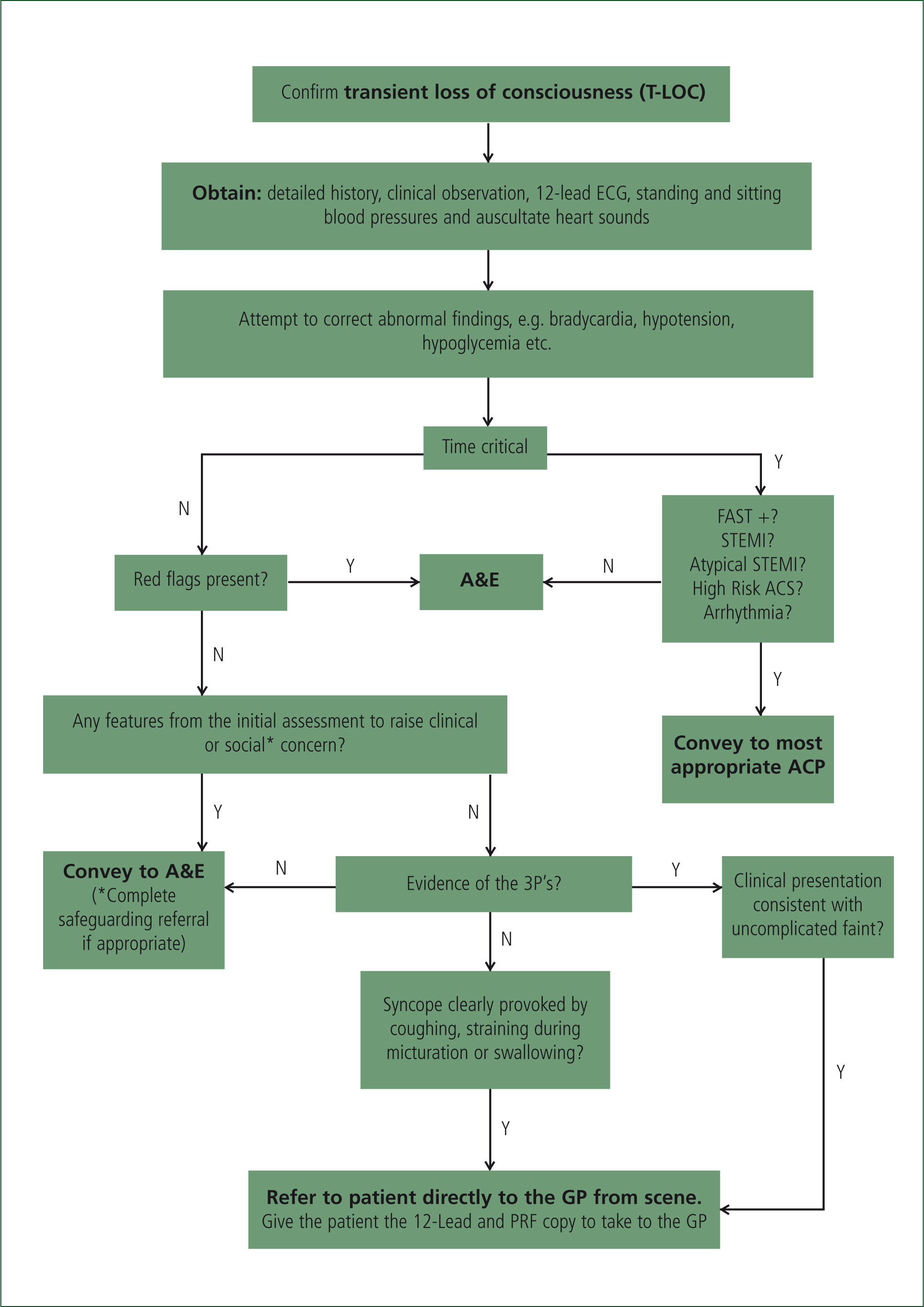

T-LOC by its nature has a quick onset, short duration, and spontaneous complete recovery; this makes it challenging to manage (Viqar-Syed et al, 2013). While there are different tools that have been proposed for use in hospital to distinguish individuals who can be safely discharged from those who warrant a prompt hospitalisation, it is acknowledged that less work has been undertaken in the pre-hospital setting (Costantino and Furlan, 2013), and there is little help for pre-hospital clinicians making conveyance decisions (Edwards, 2012). A prompt card (Box 1) and flow chart (Figure 5) have been developed as a result of this clinical audit to assist ambulance clinicians managing T-LOC patients.

| Detailed history: |

|

|

Standing blood pressures:

|

Heart sounds:

|

|

The 3 P's

|

Don't forget:

|

|

Examine the ECG for the following:

|

|

|

Red Flags:

|

Diagnosis:

|

|

GP or hospital?

|

|

The prompt card aims to encourage a full analysis of the patient's history with questions specific to T-LOC and remind ambulance clinicians of the need to measure both standing and sitting blood pressure, and listen to patients' heart sounds. The prompt card also lists common ECG abnormalities and allows for recognition of ‘red flags’ for T-LOC patients, as well as a recommended management plan for these patients. In addition, the flow chart reinforces the requirement to ensure that patients whose ECGs show abnormalities receive a speciality referral as soon as possible, to determine the underlying cause of the T-LOC. Most patients with T-LOC have fully recovered by the time they are first seen by a medical practitioner in hospital (Benditt and Adkisson, 2013), therefore the pre-hospital record is vital to ensuring all of the information is available for an informed decision to be made.

The flow chart will encourage more direct referrals so that GPs are well informed of their patient's history, assessment and ECG at the time of the incident, allowing them to appropriately manage the patient (NICE, 2010).

More recently, NICE have also released a quality standard aimed at ambulance clinicians, as well as primary and secondary care professionals, that includes six statements focusing on history taking, assessment, ECG interpretation and referral, which aim to improve care provided to patients who have experienced T-LOC (NICE, 2014; Wise, 2014).

Limitations

The clinical audit was conducted on a small sample in a select area of London. However, we have no reason to believe that the rest of London would be any different.

Conclusions

Overall, the clinical audit showed that standard clinical practice was high but has also identified areas of practice more specifically to T-LOC that require improvement. T-LOC is not given enough consideration in the pre-hospital setting, meaning that those patients whose T-LOC has a potentially serious underlying cause may not be identified and managed appropriately. It is hoped that the use of the prompt card and flow chart will lead to improvement.