Major trauma is a significant cause of morbidity and mortality globally and, while trauma deaths are more prevalent in less economically developed countries, death from trauma remains a significant issue in the UK. The National Audit Office (NAO) (2010) estimates that there are 20 000 cases of major trauma per annum, resulting in approximately 5400 deaths and pelvic fractures are present in 20–25% of patients who have sustained multi-system trauma (Burkhardt et al, 2014). Pelvic fractures usually result from high-energy trauma such as road traffic collisions, falls from height and crush injuries (Jain et al, 2013), and can result in exsanguination and death.

While the physical and economic impacts of major trauma are clear, the human cost is less visible and the effect of such experiences on the individual and their mental health, as well as their families, should not be underestimated.

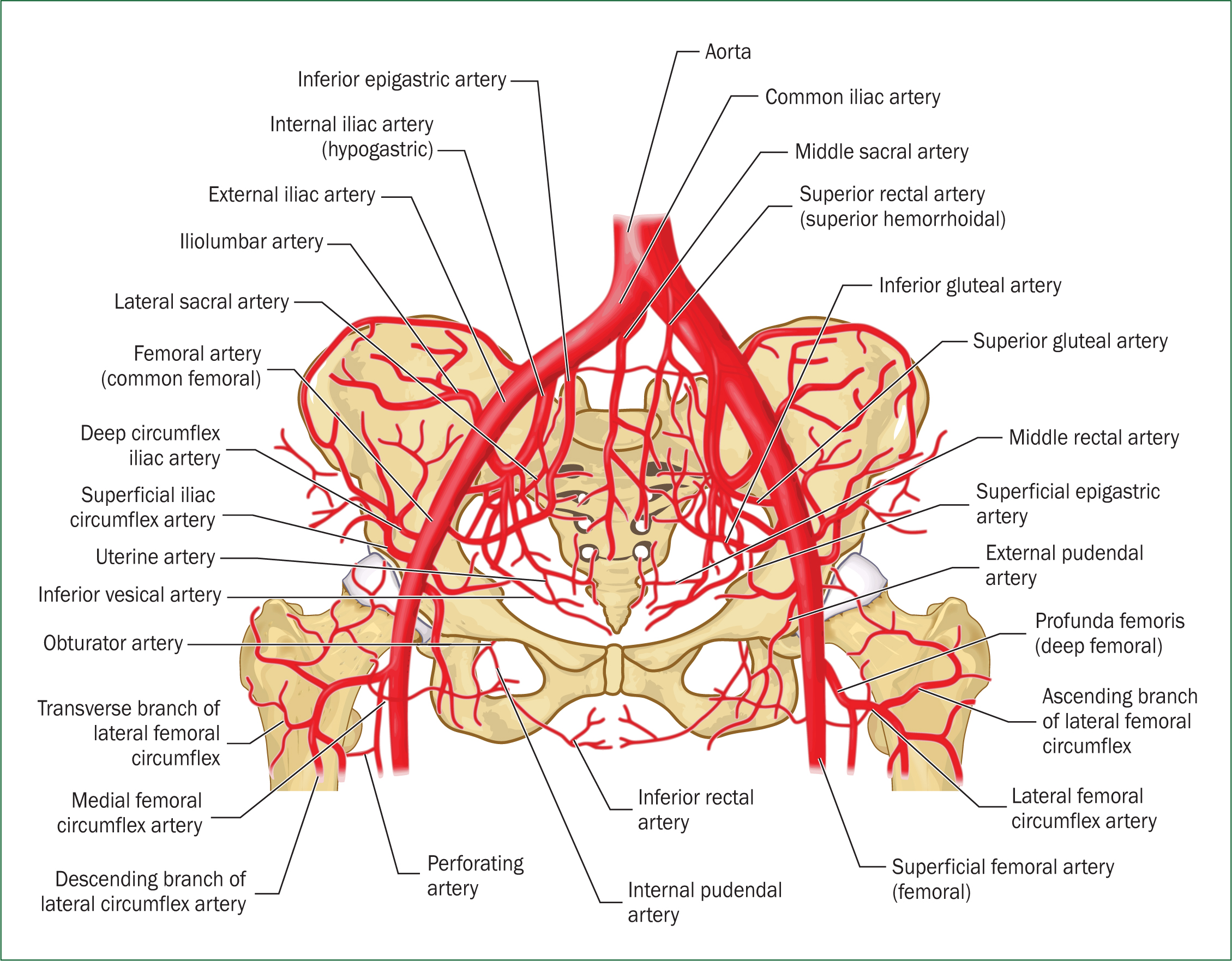

To better appreciate the nature of pelvic injuries, it is imperative to have a good understanding of the underlying anatomy. The pelvic ring is a bony ring that is formed by the ligamentous juncture of the sacrum and both innominate bones (Burkhardt et al, 2014). This normally provides a stable structure for the neurovascular and visceral structures of the pelvis. The anatomy of the pelvis with its vascular system is shown in Figure 1.

When pelvic fractures occur, haemorrhage typically stems from structures such as the iliac arterial branches, the presacral venous plexus or the large bulk of cancellous bone (Naseem et al, 2018). Disrupted compartments in the retroperitoneal space have limited capacity to tamponade and there is a high risk of exsanguination. Indeed, unstable pelvic fractures can lead to hypovolaemic shock and traumatic cardiac arrest resulting from exsanguination. An estimated 9–15 units of blood can be lost which, in some adults, equates to their entire circulating blood volume (Veith et al, 2016). Other causes of mortality include concomitant injuries, multi-organ failure and acute respiratory distress syndrome (Scemama et al, 2015). It is critical that a high index of suspicion is maintained for all patients who present with major trauma to ensure these injuries are identified early and that interventions are initiated with minimal delay.

Pelvic trauma should be suspected in all patients who have experienced a significant mechanism of injury and clinical gestalt should be employed. If pelvic fracture is suspected, initial management should be started in accordance with the Advanced Trauma and Life Support guidelines (American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma, 2008) and, for prehospital practitioners, the Joint Royal Colleges Ambulance Liaison Committee (JRCALC) (2019) guidelines.

Haemorrhage control should be prioritised and this is best achieved by manual stabilisation of the pelvic ring through the expedient application of a pelvic binder. While the pelvic binder may not reduce arterial haemorrhaging (because of an insufficient tamponade effect within the deep pelvic tissues), it does produce sufficient tension if applied correctly to reduce haemorrhage from the presacral venous plexus to have an impact. The application of pelvic binders is thought to tamponade bleeding by diminishing the pelvic volume and accelerating the clotting of a pelvic haematoma (Hsu et al, 2017). The risk of secondary haemorrhage can also be reduced as the binder prevents bony elements from shifting and further disrupting pelvic vasculature.

If the pelvic binder is to be effective in reducing symphysial diastasis and arresting haemorrhage, accurate placement is critical. Pelvic binders have been shown to be most effective when applied at the level of the greater trochanters (Bonner et al, 2011).

However, multiple studies have demonstrated that pelvic binders are often applied suboptimally. In a military setting, inaccurate placement was reported in 50% of cases, with 39% of all binders being placed superior to the optimal trochanteric region (Bonner et al, 2011). This was also found in a civilian setting where accurate placement was assessed using computerised tomography (CT); here, 40.9% of binders were found to be have been placed too high and 10% too low (Naseem et al, 2018).

The reasons for inaccurate placement are multifactorial and may be attributed to the difficulties of working in austere environments or a lack of underpinning theoretical knowledge. This was assessed in a 2013 study, which concluded that only 38.9% of emergency department (ED) registrars were able to identify the greater trochanters as the key anatomical landmarks for pelvic binder application (Jain et al, 2013). These studies sought to assess the accuracy of pelvic binder application using radiological methods within the EDs. It could be argued that such binders were placed accurately on scene and shifted during evacuation to secondary care. This seems unlikely, and the more convincing explanation for poor pelvic binder placement seen using radiological methods in EDs is that the pelvic binders were placed incorrectly on scene by prehospital practitioners.

Thus, the aim of this study is to investigate the initial placement of pelvic binders by a cohort of UK student paramedics with a null hypothesis that a high degree of misplacement will be observed consistent with the existing evidence base.

Methodology

Purposeful convenience sampling was used to recruit student paramedics at the College of Paramedics' UK National Student Conference and one UK higher education institution between November 2018 and December 2018. The research team indiscriminately recruited student paramedics from all three academic levels and this heterogenous cohort had a spectrum of experience, from those who had recently started their studies to those who had spent time in clinical practice and had nearly completed their programme.

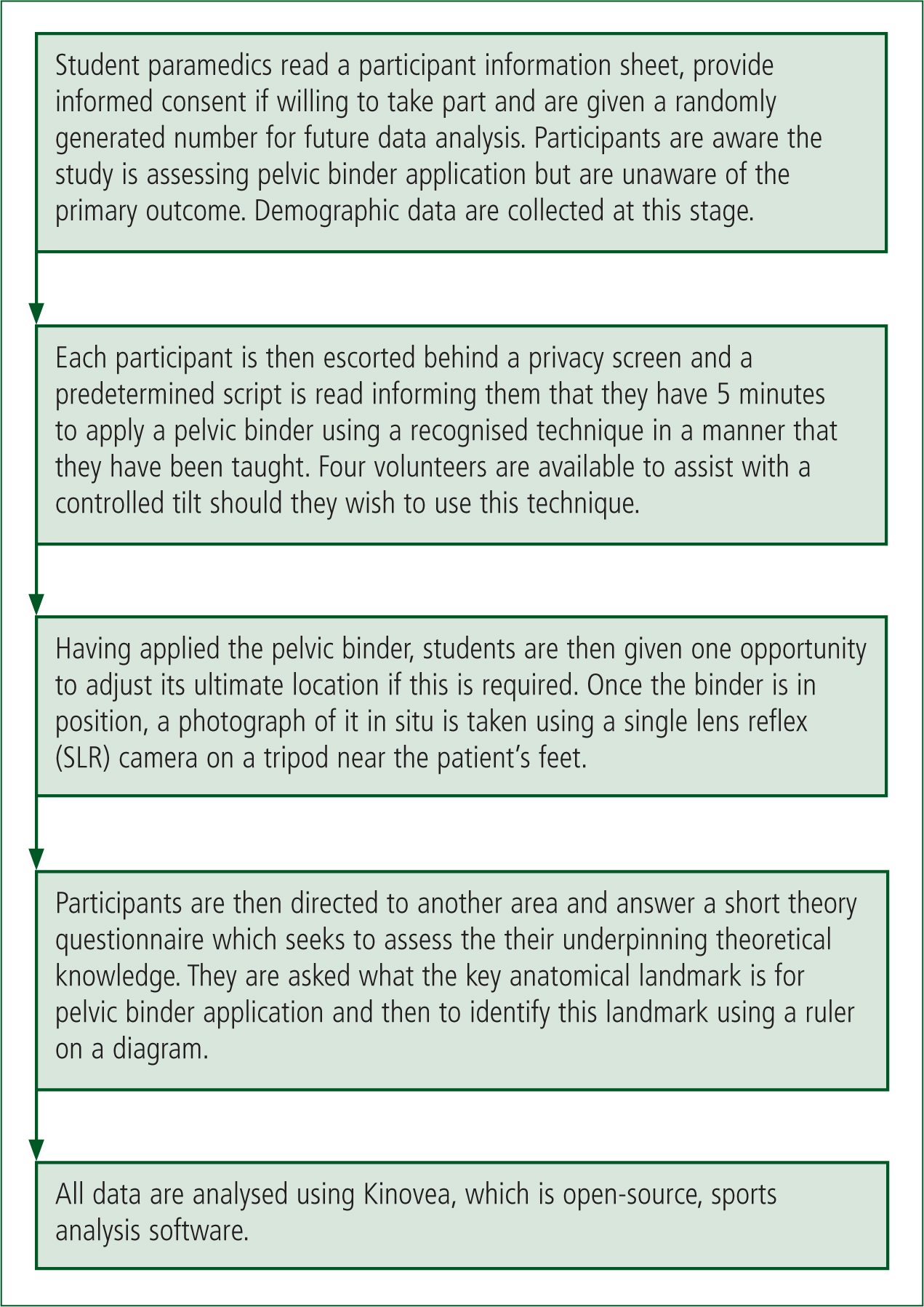

Participants were given an information sheet and asked to give consent before the study started. Demographic data were collected and students were directed to the practical stage of the research. Although participants were informed that the research team was assessing pelvic binder application, they were blinded to the specific primary outcome.

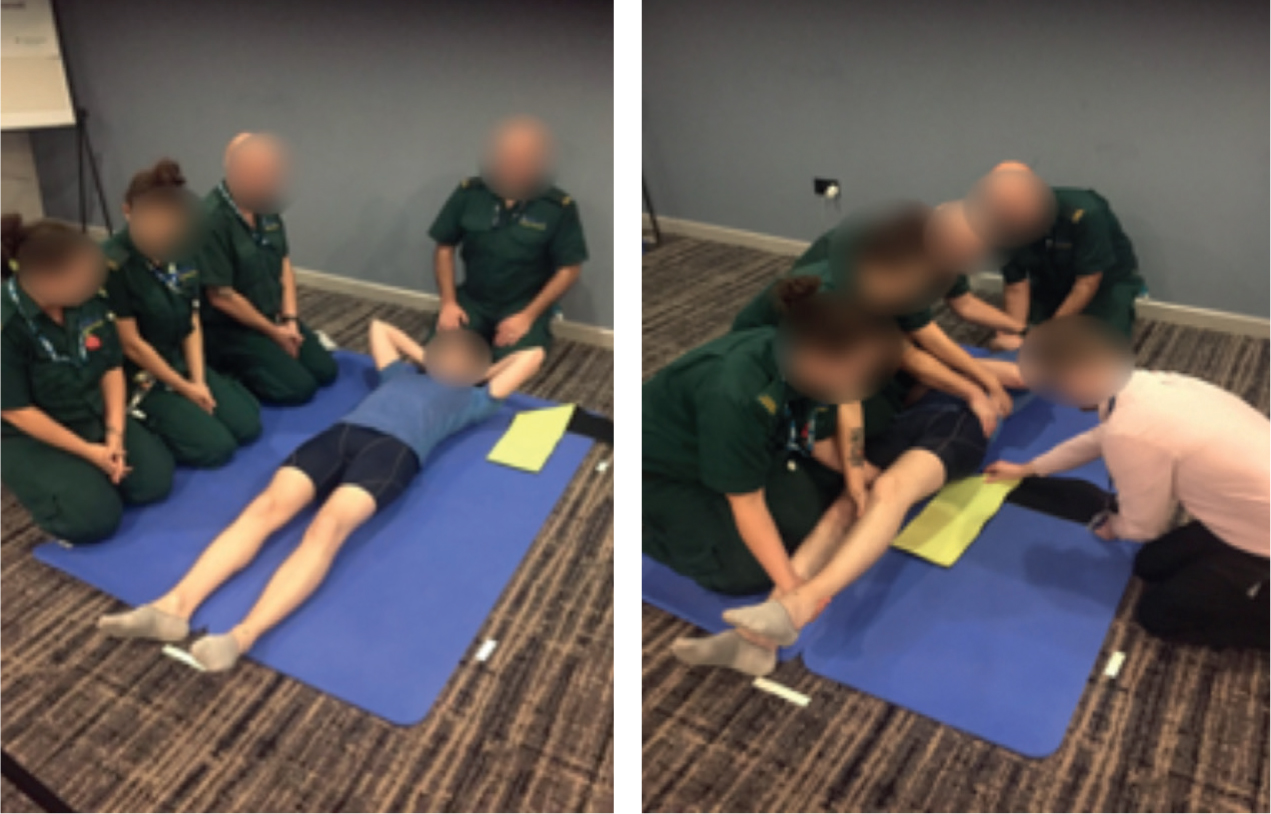

A healthy, adult, male subject with a body mass index (BMI) of 21 agreed to assist with the research and he was positioned supine on a cushioned sports mat. Although pelvic binders should be applied directly to the skin to prevent the development of pressure ulcers, this was deemed inappropriate and the subject wore tight-fitting cycling shorts to ensure maximal palpation of the greater trochanters was possible while maintaining his dignity.

Four volunteers were positioned close to the subject, one superiorly and three laterally. A commonly used type of pelvic binder had been pre-cut to fit the patient and was placed next to his shoulder (Figure 2). Near to the subject's feet was a high-resolution single lens reflex (SLR) camera mounted on a tripod, which was used to take high-resolution photographs of the pelvic binder placement by the participants. The cushioned sports mat was secured in place to prevent movement and two crosses, 1500 mm apart, were marked on the mat to act as a calibration reference point for digital distance measurement after the binder had been applied.

| Mean | SD | 95% CI | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left trochanter (mm) | −4.8 | 60 | −122.5–112.8 | −136.6–141.9 |

| Right trochanter (mm) | −8.2 | 64.1 | −133.9–117.5 | −141–158.3 |

| Mean positioning (mm) | −6.5 | 61.8 | −127.7–114.7 | −138.8–150.1 |

| Application time (s) | 149.4 | 48.4 | 54.6–244.3 | 61–270 |

A physiotherapist registered with the Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC) who had expertise in musculoskeletal physiotherapy assessed the subject and located the lateral malleolus and greater trochanters on both lower limbs. The distance between these two bony landmarks was measured and recorded.

A pelvic binder was then applied to the subject by two senior lecturers in paramedic science and expert consensus was sought to assess the accuracy of the application. A photograph was then taken of the optimally positioned pelvic binder and the median distance from the subject's lateral malleolus of both right and left lower limbs to the midpoint of the pelvic binder was measured using Kinovea, an open-source sports analysis software programme. This acted as the reference value for the optimally applied pelvic binder. This distance was 842 mm and the pelvic binder was deemed to have been applied correctly if the midline of the pelvic binder was positioned within the 792–892 mm range. This zone of acceptable application was based on an educated estimate of what the authors considered to be the distance between the greater and lesser trochanters in this subject.

Secondary outcomes sought to assess the underpinning knowledge of student paramedics and this was assessed after the pelvic binder had been applied. In this two-stage, paper-based assessment, student paramedics were asked to state the key anatomical landmarks required for effective pelvic binder application and, second, to locate these landmarks on a prepared diagram of pelvic anatomy by drawing a horizontal line where they thought the midline of the pelvic binder should be placed. The methodology's processes are shown in Figure 3.

Ethical considerations

The research received ethical approval from the research ethics committee of the University of Wolverhampton. All subject data were completely anonymised, confidentiality was maintained throughout, and all data were stored in accordance with the General Data Protection Regulation.

Results

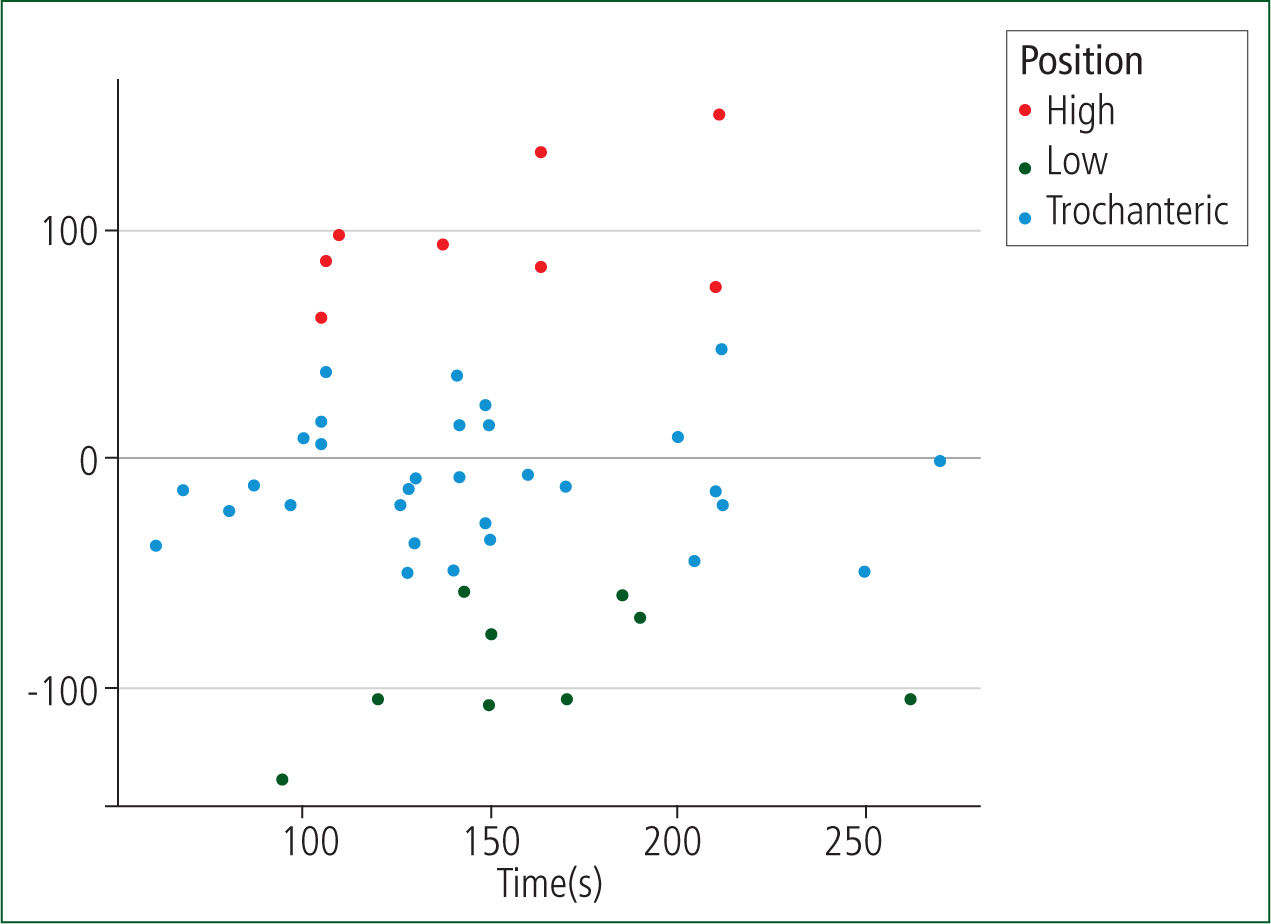

Fifty people took part in the study, of whom 20 (38%) were recruited at a national conference attended by student paramedics from NHS ambulance services and higher education institutions from across the UK, and 32 student paramedics (62%) were recruited from one UK higher education institution. Two participants were unable to apply the pelvic binder within the allotted time frame and incomplete data were recorded for one other participant, so these were eliminated, leaving 49 participants in the study. Of the remaining 49 participants, 32 (67%) applied the binder correctly. Of those who placed the pelvic binders incorrectly, nine (18%) applied it too low and eight (16%) too high (Figure 4).

Discussion

The primary outcome measure for this research project was the accuracy with which student paramedics are able to apply pelvic binders. A high degree of misplacement was evident, with 34% of student paramedics being unable to optimally apply a pelvic binder. While this is generally consistent with published research and corroborates the existing evidence base, there were some clear differences regarding the results obtained in the current study.

Previous research demonstrated a significant percentage of inaccurately applied pelvic binders and, while many binders are applied too high (Bonner et al, 2011; Naseem et al, 2018), in the present study, 18% were deemed to be too low and 16% too high. Although the reasons for this are unknown, it is likely that the recruitment of a high number of participants from one university may have influenced the results as they may have been aware that pelvic binders are often placed too high so compensated accordingly. Secondary outcomes were used to assess the underpinning theoretical knowledge of student paramedics and 75% of participants were able to identify the greater trochanters as the key anatomical landmarks for pelvic binder application. This would suggest that many student paramedics are aware of where the pelvic binder should be placed but that this does not translate into locating these landmarks in a controlled setting. Similarly, after student paramedics were asked to identify this landmark by drawing a horizontal line using a ruler on a diagram of pelvic anatomy, only 37% of student paramedics were able to do so. This result was similar to the number of student paramedics who were unable to optimally apply a pelvic binder to a human subject within the practical element of our research project (34%), although the authors have not established a causal relationship. It would appear that a theory-practice gap exists where student paramedics have some insight into the theory underpinning pelvic binder application but this knowledge is poorly applied, even in a simulated setting.

This study has not determined the reasons why student paramedics are unable to locate these anatomical landmarks. This is likely to be multifactorial, and causative factors may include any or all of the following: incorrect initial teaching; inconsistent teaching resulting from the involvement of visiting lecturers in clinical skills teaching; a result of peer-supported learning if peer supervisors have not fully grasped key concepts; poor knowledge/skill retention by student paramedics; failure to emphasise and understand the implications of poor pelvic binder application; and suboptimal practice-based education from practice educators. A lack of exposure to patients presenting with major trauma is another potentially contributory factor. Between 1 April 2016 and 31 March 2017, the London Ambulance Service (2017) responded to 6068 patients with major trauma, which accounted for just 0.5% of the service's workload, and this lack of exposure to major trauma is reflected nationally.

If student paramedics are not applying pelvic binders correctly, even in a controlled setting, this raises two key questions that might form the basis of future research:

Limitations

A number of limitations may have affected the dataset obtained in the current study. Previous studies have used radiography and CT to locate both greater and lesser trochanters (Bonner et al, 2011; Naseem et al, 2018) but financial constraints, and the ethical considerations of unnecessary radiation exposure without clinical necessity, meant that the researchers in this study had to use clinical expertise and expert opinion to estimate the location of the lesser trochanters as a surrogate for the zone of acceptable application. The lack of radiological imaging may have affected the accuracy of the results, as radiography or CT are more reliable in locating anatomical landmarks (Naseem et al, 2018).

Furthermore, paramedic students were recruited from just two sites—a national conference and a single higher education institution—resulting in some degree of selection bias (Bonner et al, 2011). The sample is small and is not powered to reach statistical significance.

Although the authors believe their results are interesting and provide some important insight into the ability of this cohort, the generalisability and external validity of this study could be questioned.

Conclusion

This research has sought to assess the accuracy with which student paramedics apply pelvic binders and, although limitations exist, this study contributes to the existing evidence base.

The results demonstrated there was a high degree of misplacement in this cohort, with 34% of pelvic binders being placed outside the zone of acceptable application. This appears to be consistent with previously published research and the null hypothesis. However, why pelvic binders are not being placed accurately has not been determined.

Secondary outcomes were used to assess the underpinning knowledge of student paramedics. Many of them were able to state what anatomical landmarks were required for accurate placement of pelvic binders and it is therefore a possibility that a theory-practice gap exists and student paramedics are simply unable to locate these landmarks in real patients. This represents both a challenge and an opportunity for UK higher education institutions to review the manner in which pelvic binder application is taught to the next generation of prehospital practitioners.