When presented with a patient with an undiagnosed neurological condition, how do you decide how to proceed? In the challenging out-of-hospital environment intuition or experience may be your main resource, but could also be a hindrance. It is difficult to define intuition, but it is often seen as incorporating rapid perception to make decisions, and not being aware of the processes involved (Gobet and Chassy, 2008). With paramedics being required to make more and more decisions as part of their practice, including discharging at scene, treat and refer systems and ultimately not transferring all patients to the ED, it is vital to understand the decision-making processes undertaken. By thoroughly understanding the processes that paramedics undertake, education can be targeted to incorporate these. Training practitioners to actively avoid the pitfalls of these techniques should help to reduce the likelihood of error in the future.

Background

Firstly, it is important to consider why particular decisions are made, whether diagnoses are correct and what assumptions are made about the patient. It is pertinent to reflect on whether there were any errors and the reasons for them, in order to guide future practice.

A common place example faced by paramedics might be a patient presenting with, or following, an unresponsive episode. It is easy to make assumptions and to make an initial diagnosis. This article will provide a succinct description of a case from clinical practice, highlighting why the decision-making process is important to patient outcomes, how this is undertaken and the role that experience.

Case presentation

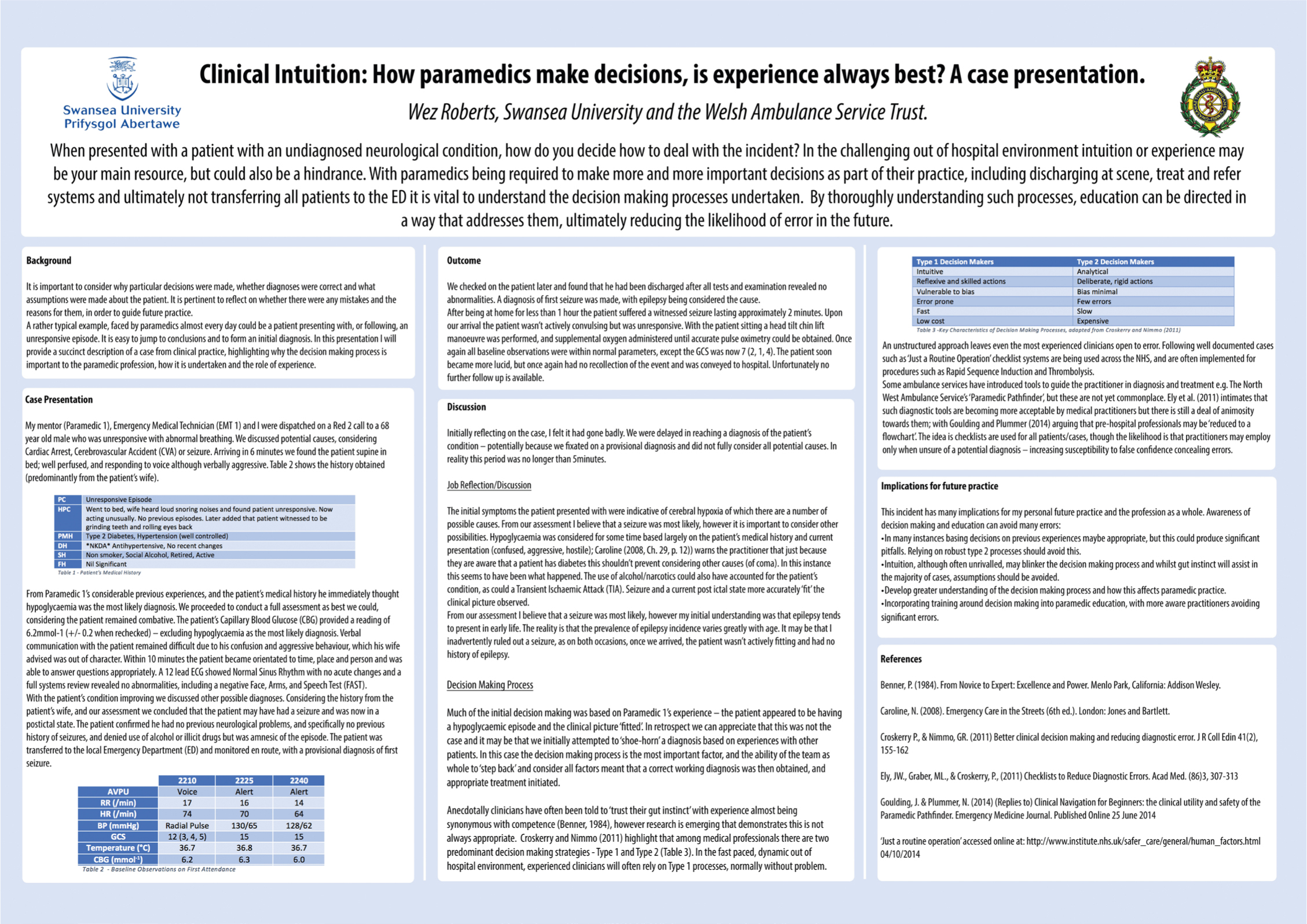

My mentor (Paramedic 1), emergency medical technician (EMT 1) and I were dispatched on a Red 2 call to a 68-year-old male who was unresponsive with abnormal breathing. We discussed potential causes, considering cardiac arrest, cerebrovascular accident (CVA) or seizure. Arriving in 6 minutes we found the patient supine in bed, well perfused, and responding to voice although verbally aggressive. Table 2 shows the history obtained (predominantly from the patient's wife).

| PC | Unresponsive Episode |

| HPC | Went to bed, wife heard loud snoring noises and found patient unresponsive, now responsive but acting out of character—aggressive and non-communicative. No previous episodes. Later added that patient witnessed to be grinding teeth and rolling eyes back. No preceding trauma. |

| PMH | Type 2 Diabetes, Hypertension (well controlled) |

| DH | *NKDA* Antihypertensive, No recent changes |

| SH | Non smoker, Social Alcohol, Retired, Active |

| FH | Nil Significant |

| 2210h | 2225h | 2240h | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AVPU | Voice | Alert | Alert |

| RR (/min) | 17 | 16 | 14 |

| SpO2 (%) | 96 | 97 | 97 |

| HR (/min) | 74 | 70 | 64 |

| BP (mmHg) | Radial pulse | 130/65 | 128/62 |

| GCS | 12 (3, 4, 5) | 15 | 15 |

| Temperature (°C) | 36.7 | 36.8 | 36.7 |

| CBG (mmol-1) | 6.2 | 6.3 | 6.0 |

From Paramedic 1's considerable previous experiences, and the patient's medical history he immediately thought hypoglycaemia was the most likely diagnosis. We proceeded to conduct a full assessment as best we could, considering the patient remained combative. The patient's capillary blood glucose (CBG) provided a reading of 6.2 mmol-1 (±0.2 when rechecked at 15 minute intervals)—excluding hypoglycaemia as the most likely diagnosis. Verbal communication with the patient remained difficult due to his confusion and aggressive behaviour, which his wife advised was out of character. Within 10 minutes the patient became orientated to time, place and person and was able to answer questions appropriately. A 12-lead ECG showed normal sinus rhythm, at a rate of 70/min with no acute changes and a full systems review revealed no abnormalities, including a negative face, arms, and speech test (FAST).

With the patient's condition improving we discussed other possible diagnoses. Considering the history from the patient's wife, and our assessment, we concluded that the patient may have had a seizure and was now in a postictal state. The patient confirmed he had no previous neurological problems, and specifically no previous history of seizures, and denied use of alcohol or illicit drugs but was amnesic of the episode. The patient was transferred to the local emergency department (ED) and monitored en route, with a provisional diagnosis of first seizure.

Outcome

We made enquiries on the patient later and found that he had been discharged after all tests and examination revealed no abnormalities. A diagnosis of first seizure was made, with epilepsy being considered the cause.

After being at home for less than 1 hour the patient suffered a witnessed seizure lasting approximately 2 minutes. Upon our arrival the patient wasn't actively convulsing but was unresponsive. With the patient sitting a head tilt chin lift manoeuvre was performed, and supplemental oxygen administered until accurate pulse oximetry could be obtained. Once again all baseline observations were within normal parameters, except the GCS was now 7 (2, 1, 4). The patient soon became more lucid, but once again had no recollection of the event and was conveyed to hospital. A formal diagnosis is unavailable as we were unable to follow up on the patient's treatment.

Discussion

Initially reflecting on the case, I felt there was significant room for improvement. We were delayed in reaching a diagnosis of the patient's condition—potentially because we fixated on a provisional diagnosis and did not fully consider all potential causes. Although, realistically this period was no longer than 5 minutes.

Job reflection/discussion

The initial symptoms the patient presented with were indicative of several conditions that Caroline (2008) indicates could cause cerebral hypoxia, such as a cerebrovascular accident or transient ischaemic attack, seizure, poisoning, head injury or cardiac arrest. From our assessment I believed that a seizure was most likely; however, it is important to consider other possibilities. Hypoglycaemia was considered for some time based largely on the patient's medical history and current presentation (confused, aggressive, hostile); Caroline (2008, Ch. 29: 12) warns the practitioner, just because they are aware that a patient has diabetes this shouldn't prevent them considering other causes (of coma). In this instance this seems to have been what happened. The use of alcohol/narcotics could also have accounted for the patient's condition, as could a transient ischaemic attack (TIA). Seizure and a current postictal state more accurately ‘fit’ the clinical picture observed.

From our assessment I believed that a seizure was most likely; however, my initial understanding was that epilepsy tends to present in early life. The reality is that the prevalence of epilepsy incidence varies greatly with age. It may be that I inadvertently ruled out a seizure, as on both occasions, once we arrived, the patient wasn't actively having a seizure and had no history of epilepsy.

‘Some ambulance services have introduced tools to guide the practitioner in diagnosis and treatment, e.g. the North West Ambulance Service NHS Trust's ‘Paramedic Pathfinder', but these are not yet commonplace’

Decision-making process

Much of the initial decision making was based on Paramedic 1's experience—the patient appeared to be having a hypoglycaemic episode and the clinical picture ‘fitted’. In retrospect we can appreciate that this was not the case and it may be that we initially attempted to ‘shoe-horn’ a diagnosis based on experiences with other patients. In this case the decision-making process is the most important factor, and the ability of the team as whole to ‘step back’ and consider all factors meant that a correct working diagnosis was then obtained, and appropriate treatment initiated.

Anecdotally, clinicians have often been told to ‘trust their gut instinct’ with experience almost being synonymous with competence (Benner, 1984); however, research is emerging that demonstrates this is not always appropriate. Croskerry and Nimmo (2011) highlight that among medical professionals there are two predominant decision making strategies: Type 1 and Type 2 (Table 3). In the fast paced, dynamic out-of-hospital environment, experienced clinicians will often rely on Type 1 processes, normally without problem.

| Intuitive | Analytical |

| Reflexive and skilled actions | Deliberate, rigid actions |

| Vulnerable to bias | Bias minimal |

| Error prone | Few errors |

| Fast | Slow |

| Low cost | Expensive |

An unstructured approach leaves even the most experienced clinicians open to error. Following well documented cases, such as that seen in the film ‘Just a Routine Operation’ (Thinkpublic, 2008), checklist systems are being used across the NHS, and are often implemented for procedures such as rapid sequence induction and thrombolysis.

Some ambulance services have introduced tools to guide the practitioner in diagnosis and treatment, e.g. the North West Ambulance Service NHS Trust's ‘Paramedic Pathfinder’, but these are not yet commonplace. Ely et al (2011) intimates that such diagnostic tools are becoming more acceptable by medical practitioners but there is still a deal of animosity towards them, with Goulding and Plummer (2014) arguing that pre-hospital professionals may be ‘reduced to a flowchart’. The idea is checklists are used for all patients/cases, though the likelihood is that practitioners may employ them only when unsure of a potential diagnosis—increasing susceptibility to false confidence concealing errors.

Implications for future practice

This incident has many implications for my personal future practice and the profession as a whole. Awareness of decision making and formalised education around this topic, both during initial training and as part of a CPD commitment can avoid many errors: