The term resilience comes from the latin ‘resili’ meaning ‘to spring back’. It describes an ability to recover readily from adverse events, such as illness; accidents; traumatic incidents; and in more extreme cases, disasters. A resilient community is one that has capacity to anticipate and provide a degree of protection against risks, to limit the impact of, and cope with adverse events, and bounce back rapidly. Community resilience is generally interpreted in relation to health as this broad concept. Bartley's definition (2006) is widely used:

‘The process of withstanding the negative effects of risk exposure, demonstrating positive adjustment in the face of adversity or trauma, and beating the odds associated with risks.’

Research indicates that resilience varies between and within communities. For example, two similarly located/sized settlements may differ in how resilient they are, and their capacity to cope with problems and emergencies. It has been suggested that resilient factors can afford some protection against the disadvantages of socio-economic deprivation, whereby some poor communities have lower rates of mortality than others (Mitchell, 2009).

Efforts to help strengthen resilience seek to create a supportive environment to help community members prevent or mitigate the adverse impact of negative events. Besides identifying current deficits in being able to meet population needs, it is particularly important to work with the community to foster the ‘assets’ available to develop and apply solutions. Positive attributes of community members, such as their skills; knowledge; connections, the actions they can take, and the ways they can be involved in meeting community needs can be viewed as ‘assets’ (Kretzmann and McKnight, 1993). These ‘assets’ are key to helping communities to help themselves.

The way services and support are provided by public agencies, voluntary organizations, and the private sector, can support this (Box 1). There are common factors that make resilience possible and increase people's capability. These mostly have to do with the quality of human relationships, and with the quality of public service responses to people with problems (Bartley, 2006).

Resilience can be interpreted by emergency services and government emergency planning departments in a much more specific way, as protection against large-scale civil emergencies and major incidents (Scottish Resilience Development Unit, 2011). This is an important aspect of Scottish Ambulance Service (SAS) work. In the context of major incident response planning, resilience relates to risks/events that occur relatively infrequently but have major impact. The developments outlined in the community resilience strategy will enhance the capacity of communities and services to cope with major incidents. Importantly, however, the strategy addresses the broader concept of community resilience. It sets out how SAS will work with community members and public and voluntary sector partners to enable the development of more sustainable ways to deal with ‘everyday’ health emergencies and urgent health problems to lessen their impact, and increase preventive initiatives (SAS, 2011).

Community members as promoters of resilience

Community members themselves can have a major role in promoting resilience, through their actions as an individual, and in their connections with others—family, neighbours, and the wider community. They also can promote resilience by working with public agencies, voluntary organizations and businesses to address issues affecting their community. ‘Social capital’ is a particularly important factor in terms of community members being able to support and develop resilience. It has been suggested that it can have a buffering effect, whereby areas with higher ‘social capital’ have some protection against risks to health and wellbeing (Friedli/World Health Organization (WHO) Europe, 2009).

Definitions of ‘social capital’ vary, although generally describe features of a community that enable mutually beneficial collective action (Halpern, 2005). The Edinburgh Health Inequalities Standing Group definition (2009) draws together the key themes—’Social capital ‘encompasses the resources people develop and draw on to increase their sense of self-esteem, their sense of connectedness, belonging, and ability to bring about change in their lives and communities.’ One important element is ‘social support’, including informal support, e.g between family members, friends, and neighbours; and formal support, e.g volunteer befrienders and community first-aiders. Second is the extent people are informed and involved—awareness of issues and resources in their community, as well as willingness and opportunity to participate and influence decisions affecting their community.

How can public services and the voluntary sector enable the development of community resilience?

Community resilience cannot be ‘produced’ by public or voluntary organizations, instead their actions can enable and support local people in developing the resilience of their communities. Resilience can, however, be supported and enhanced by the way public services are provided, and the services and support given by the following:

Co-production: working together

For each of these activities to be effective and sustainable, it is crucial that they are planned and delivered in partnership with local people. This can ensure services more closely address community needs. Importantly, it can also support and develop the resources provided by local people themselves. This is ‘co-production’. It involves an ‘active relationship between public agency staff and service users as co-workers’ and ‘engaging the assets within communities (that is) the resources of community members, e.g skills, knowledge, experience, time’ (New Economics Foundation, 2008). Community and voluntary organizations can play an important role in enabling and supporting community members to take a role in co-production. Businesses may also seek to support community resilience, support client and employee wellbeing, and fulfil ‘social responsibility’ objectives.

The co-production approach is pivotal to strengthening community resilience. One example is where SAS held discussions in 2010 with community members and other local services on the island of Luing in Argyll, seeking a practical, cost-effective solution to provide faster patient evacuations by air. The resulting ‘co-produced’ service involves local fire-fighters deploying landing lights to enable an air ambulance to land, and using a field as a landing site with the cooperation of a local farmer.

The development of many ‘community first responder’ schemes provides another illustration. Often community members have approached SAS with a request to establish a volunteer scheme to provide an immediate response to local health emergencies. Local people have then been recruited and trained to provide immediate lifesaving support prior to the arrival of SAS resources. Schemes are run by community member co-ordinators, with support from voluntary and public organizations, as well as SAS. In this way, SAS is enabling local people to be directly involved in enhancing their communities’ resilience.

Why is the Scottish Ambulance Service engaging in this agenda?

Policy context

Community resilience was identified as a key objective in the SAS strategic framework Working together for better patient care (SAS, 2010). This commitment can be seen in the context of wider policy and health system developments. In Better Health, Better Care (Scottish Government, 2007), the Scottish Government outlined its vision for the NHS—a shift in the balance of care from acute to primary and community care; equity of access; greater prevention and health improvement, and partnership with patients. All are sub-themes of the community resilience agenda, as will be illustrated later in the article.

The concept of ‘co-production’ was identified as a key mechanism by which services and communities can work together as partners to better address community needs (Scottish Government, 2007). The actions outlined for strengthening community resilience also put into practice the principles of the NHS Scotland Quality Strategy (Scottish Government, 2010): collaboration, communication, continuity of care and clinical excellence.

Seeking solutions to the challenges of improving patient care

Nonetheless, it is proposed that the primary driver for SAS in seeking to enable and strengthen community resilience is the pressing need to address challenges in delivering patient care. These relate to geography, demand, changes in the wider health and social care system, and in society more broadly. For example:

The complexity of these challenges requires a more holistic response, not solely focused on the point at which they are currently encountered by the ambulance service. The breadth of the issues and actions need the active involvement of community members and partner agencies. Strengthening community resilience has the potential to deliver a range of important benefits for community members, as well as to enhance the effectiveness and sustainability of SAS functions, and reduce pressure on the wider NHS and social services.

Building blocks: how we can contribute to strengthening community resilience

Five areas of opportunity for SAS to enable and support the development of community resilience have been identified. Together they offer a ‘whole system’ approach to community resilience: from engagement, to primary and secondary prevention, to service delivery in ordinary circumstances (scheduled and unscheduled care) and in extraordinary conditions (major incident response).

Developing new and integrated service delivery models

Emergency and urgent care

This process considers how SAS can enhance its capacity to address service delivery challenges, working with community members and partners to create a more integrated system of emergency health support. A governmental working group (the remote and rural implementation group) has developed templates for service delivery, which SAS and local NHS boards will discuss with rural communities and develop local implementation plans.

A similar process will explore new emergency response models for urban areas, particularly regarding times and areas of high demand. The models encompass new ways of delivering SAS services—for example, retained services, ‘see and assess/treat’ paramedics, and ‘professional to professional’ phone support between paramedics and medical staff. Community member initiatives may also be developed to strengthen particular points in the system before or after patients are seen by SAS. These include community first responders, increasing community member first-aid skills, and providing public access defibrillators.

The air ambulance re-procurement process for 2013–20 is one illustration of community and stakeholder engagement directly influencing the ambulance delivery model, clinical care, patient experience, and the patient journey through the NHS system.

For example, ways to improve access and experience for patients with disabilities were identified. The feasibility of including improved wheelchair storage in the clinical aircraft specification is being explored, while work with service users and health boards is underway to establish a more consistent and seamless patient journey for guide dog users.

Clinical patient transport

To ensure the quality and sustainability of the patient transport service for scheduled care for patients with clinical need, SAS will work first with partners to ensure the criteria for using its patient transport service—focused on patients with clinical need, are applied consistently by referrers. Second, SAS has a role in local discussions about how to create a system of alternative transport options for patients who do not meet the clinical criteria, to ensure patients receive optimal support.

One example of how this may be achieved is the collective model developed by community transport providers in Perthshire and provides patients with a ‘one stop shop’, linking the ambulance system for booking clinical transport to support to find suitable alternatives when required.

Enabling easier access to appropriate care

A vital supporting activity is developing ‘help literacy’ among community members and referrers to enable them to make informed and appropriate decisions about the help/support they require. This has considerable potential to enable community members to receive appropriate support more directly, and to reduce inappropriate use of SAS as an emergency service. An illustration of the need for the latter is that over 12 months of 2009–10, SAS received 17 710 ‘emergency’ calls, subsequently reclassified as minor issues requiring a non-emergency response.

Developing ‘help literacy’ requires general public information in conjunction with other service providers. However, information alone may not address problematic service use in some areas/ among some population groups. Targeted work will be undertaken to identify how to enable better help-seeking and priority groups who may require particular support to access services.

In one example from North Ayrshire, SAS worked with the local authority to deliver sessions for residents and carers in nine sheltered housing schemes, giving simple emergency first aid advice, advising what to expect if they call a GP or 999 in an emergency, and how to help an ambulance crew reach patients quickly at a sheltered housing complex. This division is also a partner in the Renfrewshire ‘Message in a bottle’ scheme. The initiative places a bottle in the fridge of vulnerable individuals, containing family contact and medical information, enabling better emergency care and ensuring patients have support during and after the health emergency.

Supporting prevention activities

Developing the community's capacity to prevent and mitigate the impact of health problems that otherwise would require emergency/urgent care is vital for community resilience. Targeted prevention activity will contribute to reducing emergency and urgent calls and acute admissions, and has potential to contribute to improved community health. Other NHS boards and organizations lead on this, but SAS can make an important contribution as a partner supporting specific initiatives.

Historically, ambulance personnel have supported specific local initiatives, such as community education on road traffic accident prevention and drug abuse. Yet generally these activities have been occasional, ad hoc and out of service time. The community resilience strategy will facilitate the integration of specific prevention activities into local service delivery plans, tailored to account for service capacity and area needs. The priority issues for SAS have been identified by analysis of service use data, including highest call volume issues and issues with greatest potential for SAS involvement to complement activity by other agencies.

Examples include SAS staff engaged in self-care education for long-term condition patients and referral to appropriate support; SAS involvement in national campaigns or educational activities e.g drug/alcohol misuse; coronary heart disease (CHD) primary and secondary prevention; road traffic accidents; and supporting elderly fall prevention schemes. For example, drug and alcohol misuse is a priority for East Division and SAS has supported several partnership initiatives.

Anticipatory care

By broad definition, anticipatory care means undertaking activities intended to prevent or lessen the impact of ill health. This can include health screening, for example, via health checkup appointments for people deemed at risk who are provided with advice and referred or signposted to support. Anticipatory care may also be more opportunistic when health professionals see a patient, identifying additional risk factors and potential problems and offering advice and directing to help resources.

Anticipatory care can support community resilience by enabling community members to address health issues that may otherwise develop into serious problems. This can reduce demand for emergency and urgent care, and provides an opportunity to link people to local support resources. In several ‘pilot’ areas, SAS crews have been undertaking health checks as part of the national ‘Keep Well’ programme. There is potential for ambulance crews more widely to undertake anticipatory care screening as part of their role, particularly in areas/at times when emergency calls are fewer.

Opportunistic anticipatory care advice, referral and signposting to further sources of support can also be developed as a standard when attending to patients at home/in the community to address non-emergency issues. In one case example from analysis of frequent caller data, a patient who had called 76 times in 3 years was unable to manage their diabetes and exacerbations in their condition. Modelling the kind of response that could be undertaken in future for similar cases when first seen; the local crew visited the patient, provided diabetic self-management advice, notified the local GP, and signposted the patient and family to further support. SAS is working with partners currently to develop a care pathway for frail elderly people who fall.

Major incident resilience

Strengthening the community resources for dealing with emergency issues such as developing first-aid skills among community members, providing public access defibrillators, and developing first responder schemes also strengthens the infrastructure available to manage major incidents which have multiple casualties. This local and immediate support can support and enhance the response from the statutory emergency services, and provide a way for community members to contribute.

To effectively harness these resources to deal with a major incident requires a system of being able to quickly contact, mobilize and co-ordinate these ‘assets’. Basic public access equipment for major incident management, e.g. stretchers, could also be provided, particularly in remote communities. Deploying community first responders to support SAS and other emergency services during a major incident would be valuable. Additional major incident training and terms of reference for their support role would enable this.

Outcomes

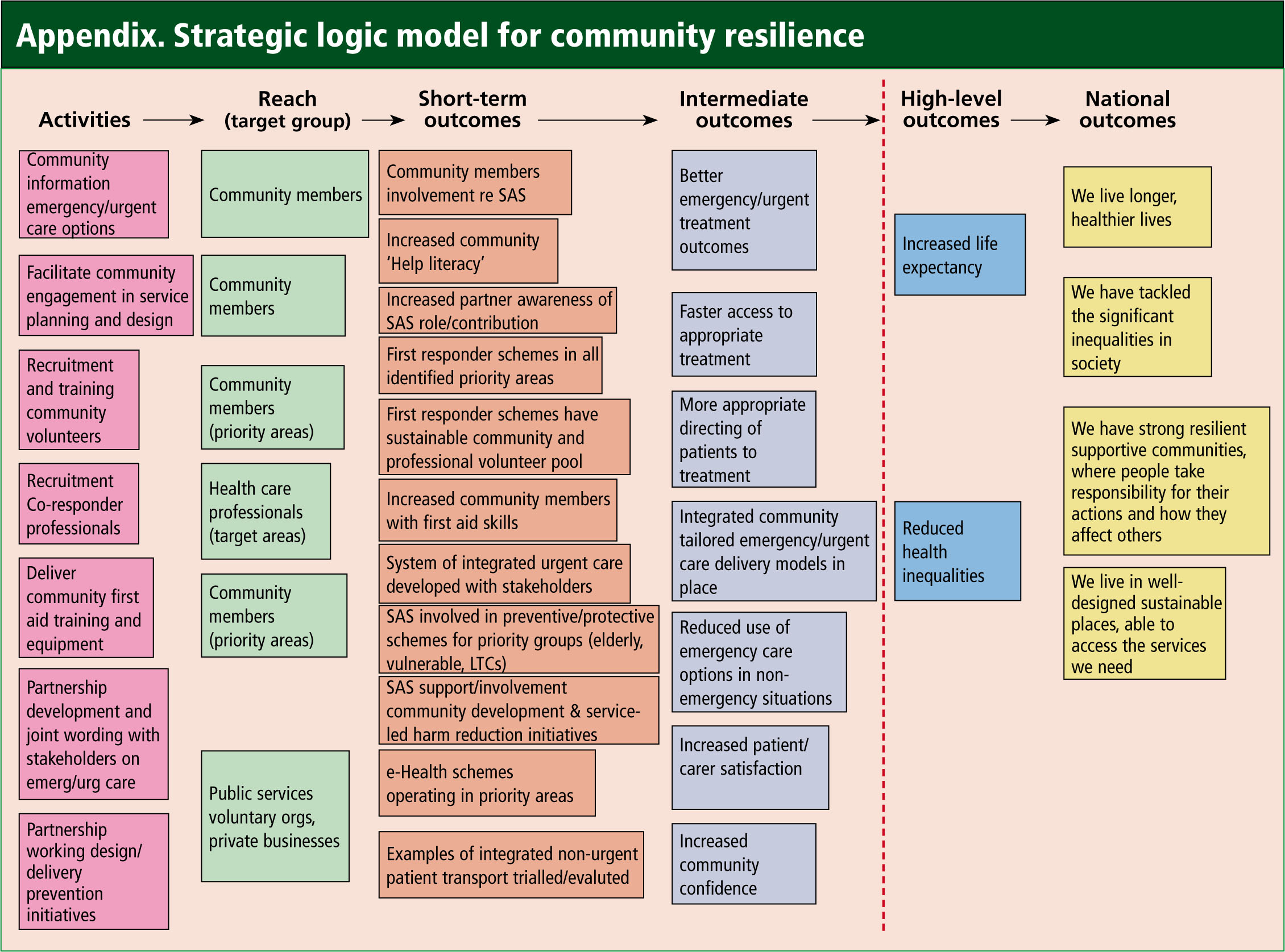

The Appendix displays a logic model for the work that will enable and support community resilience. It shows how the main areas of activity by SAS, in partnership with the community and stakeholders and system/service developments, will generate short-term outcomes. These can be expected to produce the ‘intermediate outcomes’, which together comprize the vision of a resilient community. The model shows then how progress towards community resilience can contribute to the high level national outcomes of the Scottish Government's national performance framework in relation to health, inequalities and sustainable communities.

Opportunities and challenges

Scottish policy is encouraging public services to adopt a co-production agenda and this provides a lever for agencies to work with SAS. Ironically, the scale and complexity of some of the difficulties facing partners, such as escalating hospital admissions, also provides an incentive to work with SAS to look at problems from a new angle and consider root causes. It is the case that the efficiency savings that NHS boards and other public sector agencies are required to make may influence their capacity to work with SAS to find ways to support community resilience. Voluntary organizations additionally may be constrained due to financial pressures.

Nonetheless, SAS has found partners excited and willing to work together on this agenda. Moreover, some public sector representatives appear to view the economic climate as an impetus to work more closely with others, pooling resources, and seeking solutions that tackle the root causes of costly problems that have hitherto been sidestepped or resistant to improvement.

Inevitably, community resilience is one of various competing priorities for the ambulance service, partners and even community members. SAS, like many other services, has evolved rapidly in recent years, both in the way it works and the way it works with others, and various major service are being undertaken concurrently. This could stretch capacity to deliver but on the other hand the wider changes offer an opportunity to consider how they can each support the community resilience objective. Additionally, community resilience is seen as an element of each of the service's workstreams: unscheduled care, scheduled care, e-health, workforce development, and engagement. This provides a means to influence these areas and avoid being seen as an esoteric strategic aspiration with limited practical application.

At a workforce level, there are staff resource pressures in some areas. For example, urban stations with high-demand, and community resilience actions will need to be tailored to refect this. Yet, in remote areas, resource under-utilization offers a valuable opportunity for wider action. Concerns about, and desire to have more control over safety and wellbeing are generally high priorities for community members. Nonetheless, finding ways to make involvement attractive and easy, and co-ordinating with partners to avoid confusing or bombarding a community with opportunities, are needed. Working closely with partners and community members is the essential ingredient for taking advantage of these opportunities, and developing mutually acceptable ways to overcome obstacles.

In developing its community resilience strategy, the SAS is positioning itself as an ‘enabler’ of community resilience. It is not attempting to ‘do’ or ‘fx’ communities with weak resilience, but seeks to work with community members to strengthen resilience—both by remodelling service delivery and supporting community members to take action themselves and be involved.