This literature review aims to summarise and critically appraise the relevant available evidence relating to cooling burn injuries, with a particular focus on the pre-hospital setting. The literature around knowledge and awareness of cooling, pre-hospital management of burns and the effectiveness of cooling interventions will be explored. A gap in the evidence base will direct further research needs in the field. For the purpose of this article, the term ‘burn’ will refer to thermal injuries only, owing to variations in management of burns with different pathologies.

Search strategy

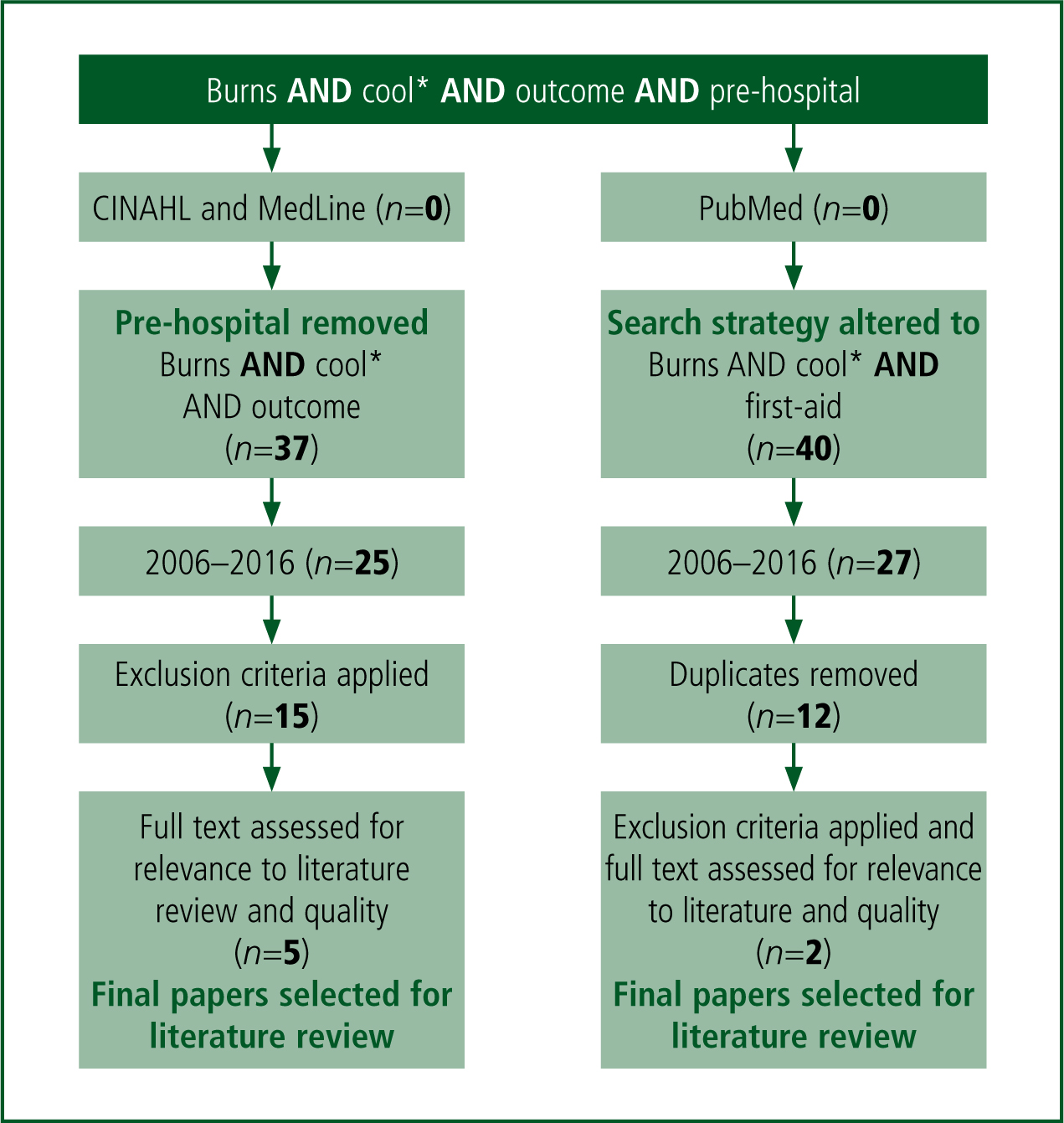

The use of the PICO technique (O'Connor et al, 2008) determined initial keywords around the topic and further synonyms were then generated. The chosen search strategy was ‘burns AND cool* AND outcome AND pre-hospital’. These keywords were searched for in the abstracts to help refine results.

Three databases were searched in order to obtain relevant articles for the literature review. CINAHL, MedLine and PubMed were chosen for their relevance and accessibility (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2017). A flow diagram detailing the search strategy can be found in Figure 1.

As a consequence of limited articles relevant to the chosen topic, the search strategy was altered for use in PubMed. ‘First aid’ (FA) was a common key word encountered in the other articles so this replaced ‘outcome’ in further searching.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied to the articles in order to focus the literature review and can be found in Table 1. Irrelevant articles were those that discussed prevention of burns, subsequent wound care for burns, or were not focused on direct initial management of burns. Once inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied, seven articles were identified as suitable for the literature review. Three key themes emerged from these articles:

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Less than 10 years old | Older than 10 years |

| Peer-reviewed | Irrelevance |

| Full text available | Animal studies |

| English language | Guidance for practice |

Theme 1: lay public knowledge

Patients and carers are often the first and only people present at the time of burn injury; therefore their knowledge of appropriate interventions is key to ensuring that FA is delivered. Cooling burns with cool running water (CRW) for the correct duration can assist in accelerating the wound healing process, and achieving improved cosmetic outcome and reduced tissue damage (Nguyen et al, 2002; Venter et al, 2007; Hamdiya et al, 2015; Stiles, 2015). In order to improve knowledge and awareness through education, it is key to first determine any existing gaps in understanding.

Two articles identified by the literature review used structured interview methods to determine participants' knowledge of appropriate FA and cooling for burns. As their sample population, Graham et al (2012) selected parents of children attending the outpatient department of one hospital. Alomar et al (2016) selected a sample consisting of parents and carers of children attending four paediatric emergency departments (EDs). In both studies, none of the children were attending hospital for burn-related injuries; therefore, it is unlikely that any parental knowledge on the subject was predetermined by being at the hospitals. However, the convenience sampling method may have biased the sample population as parents unable or unaware of how to access local medical services were not included.

Graham et al (2012) found that 73% of participants were aware of the need to cool burns with running water. However, only 35% would have carried this out for a duration of 10 minutes or more, which is defined by the authors as appropriate duration but not reflected by the British Burns Association (BBA) (2014). It is assumed that an even lower percentage of participants would have followed the 20 minute recommendation for cooling set out by the BBA. Alomar et al (2016) reflected the findings of Graham et al (2012) in producing data which demonstrated poor knowledge and awareness of cooling. In the Alomar et al (2016) study, 41% of participants had an awareness of CRW as an FA intervention—only 3% of those participants knew the appropriate duration of cooling required. Surveys such as these provide insight from the service user's perspective.

The chosen interview designs may have resulted in a larger sample size as opposed to the use of a written questionnaire, which historically has a low response rate (Williamson and Whittaker, 2014). The use of an interviewer may have introduced an element of bias, affecting validity. Not only are participants more likely to provide socially desirable answers but interviewer characteristics, such as age or gender, may also affect participant responses (Aveyard, 2014; Parahoo, 2014).

A possible limitation of the study design is that the interviews were conducted in a calm environment, allowing participants time to think carefully about their actions. In practice, FA compliance may actually be lower than the studies concluded on account of the distress associated with a painful injury. Similarly, the false interview environment lacks ecological validity (Moule and Hek, 2011) and, subsequently, may not reflect how participants would react with visual and emotional cues.

Regardless of flaws in both studies, however, they should not be overlooked as various other articles have reflected similar findings. A UK-based study carried out by Davies et al (2013) found that 43% of participants had poor or no knowledge of appropriate FA and cooling. Not only are the lay public not cooling burns as recommended, various studies have reported that 22–32% of people still treat burns with inappropriate remedies such as egg whites, toothpaste, butter, honey and ice (Ji et al, 2012; Hamdiya et al, 2015; Alomar et al, 2016).

Sadeghi Bazargani et al (2013) developed a qualitative methodology upon the findings of Graham et al (2012) and Davies et al (2013). Focus groups were conducted discussing how individuals would deliver FA and why. Many participants thought that contact with water for more than a short period may be harmful; however, the reasoning behind this belief was not further explained—possibly suggesting poor education or understanding of burns FA. Inappropriate remedies were thought to have antibacterial and analgesic effects according to the traditional and cultural beliefs of the participants. Little explanation or insight was gained by the focus groups regarding the lack of knowledge and awareness regarding cooling burns and appropriate FA. The sample size was determined through data saturation (Parahoo, 2014) and selected from burns patients in Iran. While there is limited generalisability of these findings to the UK, it should be acknowledged that qualitative research does not aim to be generalisable (Aveyard, 2014).

Theme 2: pre-hospital practitioners

Pre-hospital practitioners are often the first contact in the chain of care for burn-related emergencies. In light of poor knowledge and awareness of appropriate FA among patients and carers, it is key that pre-hospital practitioners provide the correct interventions in order to improve patient outcomes. Fianderio et al (2015) found that out of 90 patients presenting to the ED with severe burns, only 25.6% received any form of cooling before attendance. None of these patients had received cooling for an adequate duration. They concluded that the pre-hospital practitioners were providing inadequate FA; however, it is unclear how many of these patients had interventions from pre-hospital practitioners. It could also be argued that the study's findings provide weak evidence as a result the small sample size. Rea et al (2005), Breederveld et al (2011) and Tay et al (2013) also found there to be a lack of knowledge and provision of burns FA among various health professionals, including pre-hospital practitioners.

Retrospective data collected by Baartmans et al's (2016) observational study contradicted the findings of Fianderio et al (2015). Primary findings showed that direct transfer from pre-hospital practitioners resulted in higher frequency of burn cooling; however, little detail is given on the method or appropriate duration. As a secondary finding, Baartmans et al (2016) concluded that pre-hospital practitioner intervention was a strong predictor of patients not receiving analgesia. Alison and Porter (2004) also highlighted inadequate administration of analgesia. It should be noted that Alison and Porter (2004) dates back more than 10 years, and practice may have changed significantly in this time; they are however also supported by Baartmans et al's (2016) more recent findings.

Both studies looking at pre-hospital management of burns (Fianderio et al, 2015; Baartmans et al, 2016) focused on severe burns. Pre-hospital practitioners may have higher compliance in cooling and provision of analgesia in less severe burns. In severe burns, management priorities are altered and more attention is required to attend the immediately life-threatening elements such as airway compromise and fluid replacement therapy (Association of Ambulance Chief Executives (AACE), 2016).

Theme 3: effective interventions

As a result of poor compliance with FA recommendations, Wood et al (2016) investigated the impact of cooling burns with CRW prior to attending hospital. There was a significant reduction in hospital length of stay, probability of intensive care unit admission, and probability for graft surgery in patients receiving pre-hospital cooling compared with those who did not. The only variable found not to be significantly affected by cooling was mortality—there was no increase or decrease in mortality.

Current evidence already supports the benefit of CRW (Yuan et al, 2007; Bartlett et al, 2008; Cuttle et al, 2008a; 2010; Hamdiya et al, 2015). However, previous research into this area has been conducted on porcine models. While pig skin has been demonstrated to be very similar to human skin in many ways (Sullivan et al, 2001), stronger evidence comes in the form of human research. The validity of Wood et al's (2016) findings are strongly supported by a large sample of 2320 patients (Williamson and Whittaker, 2014). However, it is documented in the article that approximately 50% of patients were directly transferred to burns units. Immediate specialist care has a beneficial impact on patient outcome (Al-Mousawi et al, 2009); it is possible that this acts as a confounding variable.

Another limitation of Wood et al (2016) is that the outcomes measured are no longer considered valuable. It is now encouraged that a more holistic view be taken and factors such as cosmetic appearance, relationships and psychological wellbeing hold more importance in burns research (Falder et al, 2009; Stavrou et al, 2014; Stiles, 2015).

Wood et al's (2016) research indicates the importance of pre-hospital cooling for burns patients; however, this particular study only looked at CRW as a method of cooling. In environments where this is not available, other cooling interventions may need to be used. Cho and Choi (2017) conducted a randomised clinical trial to evaluate the effectiveness of three cooling interventions: tap water; burn cool spray; and burn shield.

Despite different brand names, burn shield, burn aid and hydrogel dressings are all a similar composition of dressings impregnated with aloe vera gel (Cuttle and Kimble, 2010). The efficacy of each cooling method was measured by skin temperature and reported pain scores. It is acknowledged by the authors that cooling should be measured using dermal temperatures (Wright et al, 2015); ethically this was not possible owing to its invasive nature.

The results found that skin temperature was significantly reduced using tap water compared with the burn spray or the burn shield. The burn shield method actually increased the skin temperature by 0.6oC. Cuttle et al (2008b) found that scar size increased with the use of a similar gel dressing. It is possible that the gel dressings retain heat from the initial injury allowing the burning process to continue. Shorter applications with frequent dressing changes may help to overcome this potential issue.

A systematic review conducted by Goodwin et al (2015) found no evidence to support the pre-hospital use of hydrogel dressings, as a cooling intervention, in burns patients. Hydrogel dressings are widely used by pre-hospital providers despite a lack of documented cooling benefit (Walker et al, 2004; Cuttle and Kimble, 2010; Fein et al, 2014). Cho and Choi (2017) provided some evidence to support the use of such dressings with data showing a significantly reduced pain score in participants receiving hydrogel dressings, compared with the other interventions. However, no additional analgesia was given during the study in order to maintain control. Adequate pharmacological analgesia may negate the need for gel dressings. A clear critique of this study is the conflict of interest created by the company who makes the coolants providing them to be used in the study (Moule and Hek, 2011).

Conclusion

The literature search has identified a need for improved education for the lay public, especially parents and carers, on FA for burns in order to help improve patient outcomes. Appropriate cooling and analgesia provision from pre-hospital practitioners has been shown to fall short of best practice—this highlights an area for improvement and calls for further research to understand causation. The beneficial effects of CRW were further demonstrated by the literature review while bringing into question the use of hydrogel dressings as a cooling intervention in the pre-hospital field. A larger evidence base is required in order to draw firm recommendations for practice.