In November 1989, the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCHR, 1989) was opened for ratification by all member countries. The UK ratified the convention in December 1991 (Children's Rights Alliance for England, no date). This has led to a number of initiatives, policies and research in Scotland which have initiated positive changes placing the child's well-being first (Scottish Executive, 2004a; Scottish Executive, 2004b; Scottish Government, 2008a; Scottish Government, 2010a).

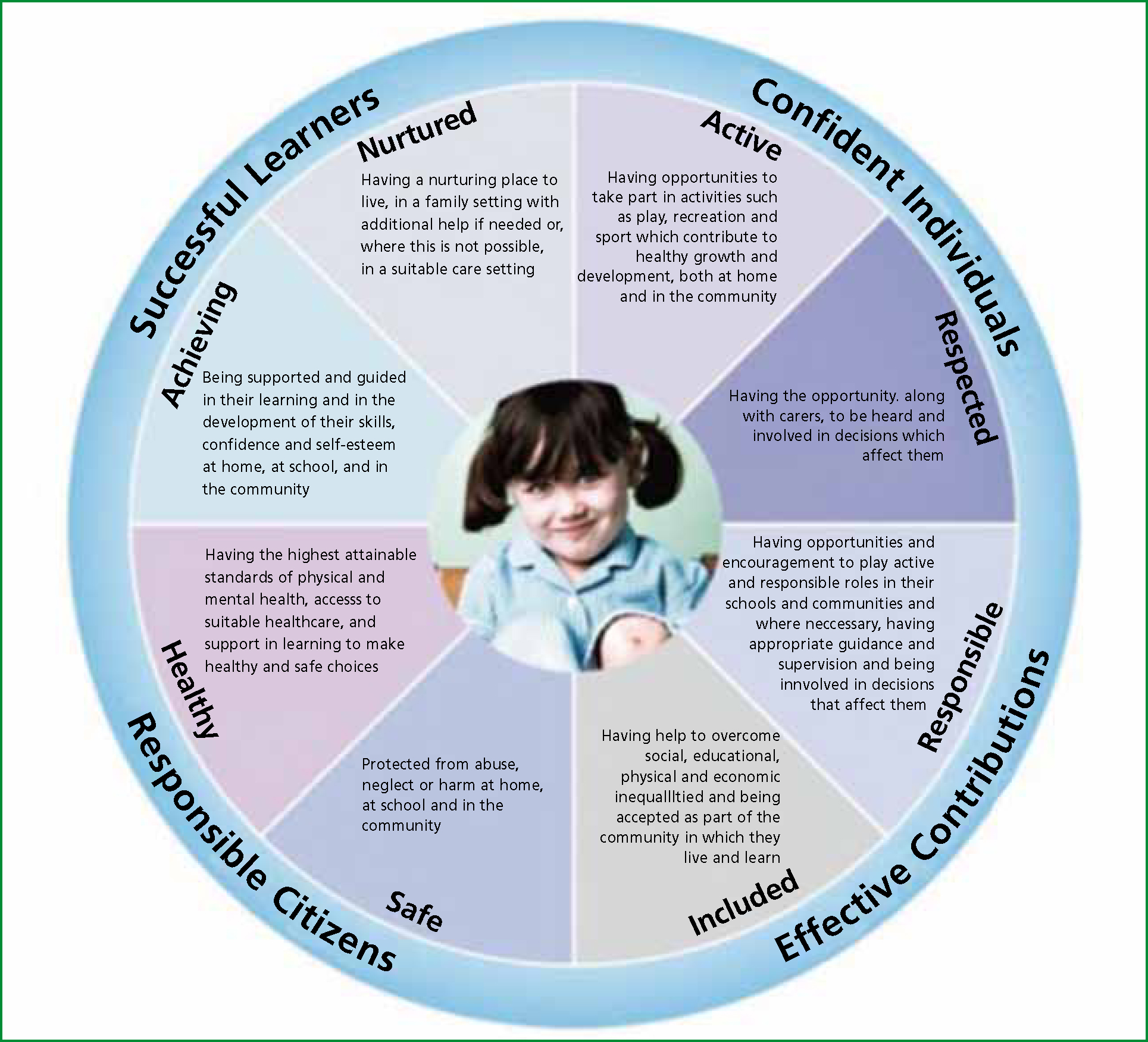

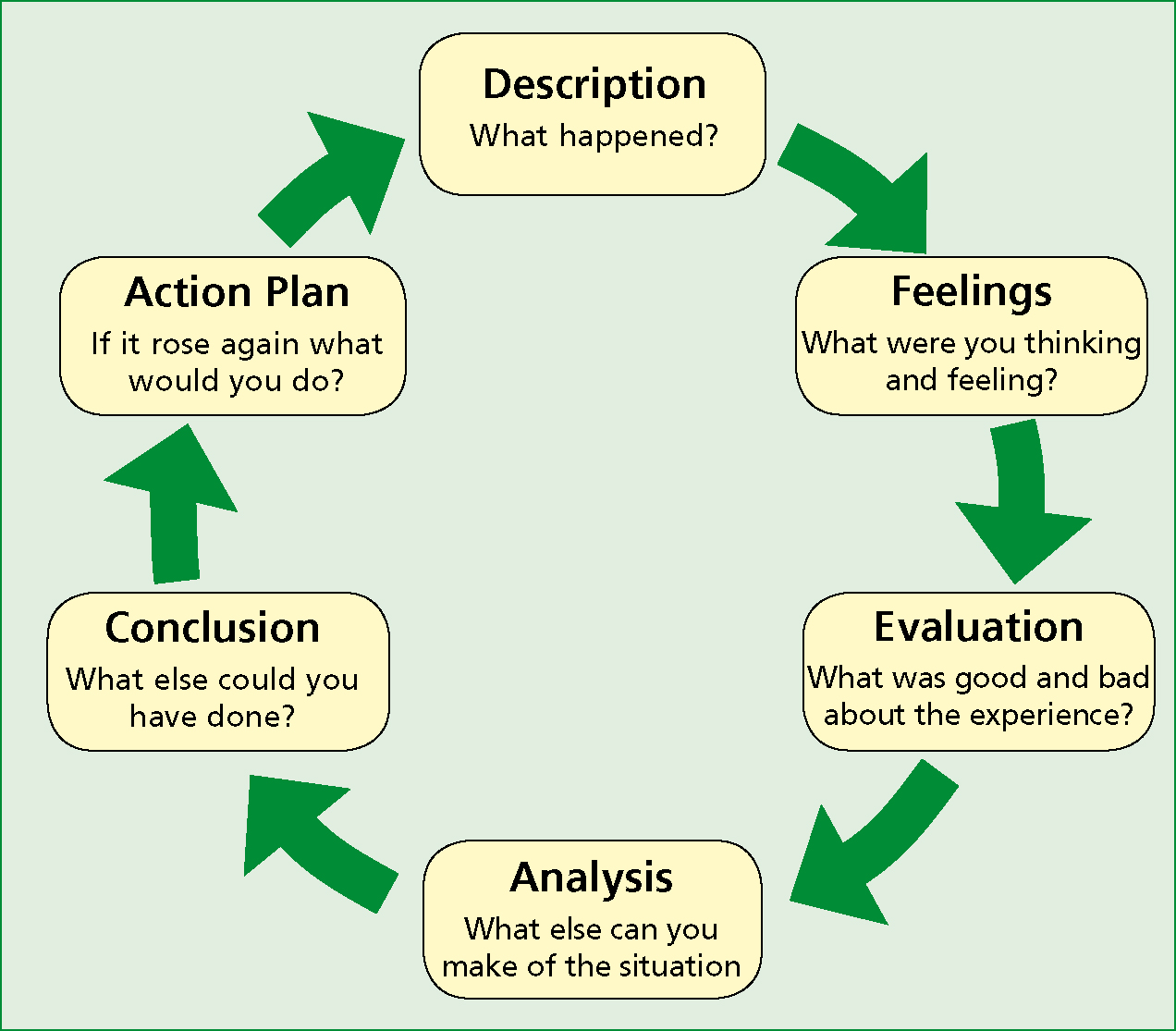

This has ultimately led to Getting it Right for Every Child (GIRFEC), the Scottish Government's key initiative aimed at creating a professional inter-agency approach to improving outcomes for all Scottish children. It envisages a fully integrated system where all children in Scotland are healthy, achieving, nurtured, active, respected, responsible, included, but above all, safe (Scottish Government, 2001) (Figure 1). There are challenges in the GIRFEC approach for health care professionals working in a multi-cultural society; one challenge is that of inclusion, empowerment and enabling shared decision-making. The following article presents a case in the form of a reflective account, which was particularly challenging in terms of these important factors in delivering safe and effective care. This reflective account is presented using the Gibbs reflective Practice Cycle (Gibbs, 1998) (Figure 2).

Description

I was called to an accident in a home environment involving a 14-year-old female in which a kitchen appliance had fallen onto her foot causing a large laceration and possibly a fracture. She and her family were from a south Asian country and had been in the UK for 5 years. She spoke very good English, but her parents’ English was not so good. During the incident, her mother mostly stayed in another room with siblings, only entering the room at a later stage to gather up some of the patient's belongings. Her father stayed in the room with her during the examination, but he seemed distant and lacking in compassion and did not display any comforting behaviours one might expect of a parent in this type of situation.

During the incident, he communicated with her mainly in their native language. After establishing that she had an isolated injury to her foot and informing her of my findings, I described the options available for pain relief and asked about how she felt about pain medication before leaving for the hospital. At this point, she communicated with her father, again, in their native language.

In his response, it seemed to me that he was encouraging her not to accept that offer, gesturing with his hand in a way I took as dismissive and shaking his head. She then declined pain medication to me in English. I accepted her opinion with very little further discussion, except to say ‘Are you sure?’ and doing my best to display a little concern with an appropriate facial expression. I dressed the wound appropriately and offered reassurance of a positive outcome. She was informed of the options of scene removal to the ambulance but despite being informed of the risks of exacerbation of the injury, she chose not to be carried down the stairs in a chair. She walked down two flights of stairs and was clearly in pain doing so. She spent the journey in some pain which she described as very minor.

Feelings

I felt that I had facilitated informed consent around the specifc issues of available treatments, as required by the Health Professions Council (HPC) Standards of conduct, performance and ethics (HPC, 2004). However, because I had been excluded from the further discussion (because of communication in a language I did not understand), I felt that I could not offer any further advice. I felt that interjecting, or asking what had been discussed may have been disrespectful to their perceptions of how I should interact with their family. After all, had this conversation been in English, I would have understood the father's comments and would have been able to offer further advice had I felt he had said anything that disempowered his daughter.

I also felt that she had not been fully informed of her right to have parents included (or otherwise) in issues relating to her health, due to my inexperience of their culture. I felt that her father had instructed her not to accept pain medication. I felt unable to discuss this with them due to my uncertainty about raising an issue which might have a cultural overtone. However, she was smiling and seemed to remain positive about the experience.

Evaluation

I can make more sense of this situation now by thinking about families from other regions in the world and how cultural differences make family dynamics vastly different to those that I am used to. Paternal influences may vary substantially depending on individual and cultural values (Lamb, 2004). and she clearly lives within that framework and cultural ethos. This was demonstrated by her wearing of traditional Asian clothing, communicating in her native language and having her father (not her mother) in the room during this event. She has grown up around this social ecology and may have had a strong attachment to her father.

‘Most Asian cultures are patriarchal, with men thought to be superior to women. Traditionally the man is the leader of the household and the main decision-maker’ (Tseng and Verklan, 2008),

Attachment figures are influenced by cultural patterns (Maldonado-Duran, 2002); but it is more likely, that she was displaying respect to her father as the main decision-maker in the family and this is likely to be the case in adverse circumstances or a situational crisis (Tseng and Verklan, 2008). I also have to consider that I may have been wrong in my interpretation of her father's hand gestures and head shaking. To me, this is a signal of disapproval or an adjunct to a dismissive comment, but this may not be the case in their cultural ecology.

Analysis

Health care workers have to be sensitive to the fact that in other cultures it may not be the mother who is the primary attachment figure (Daniel et al, 2010). Fathers and other family members may play a greater part in child cognitive development in some cultures. It has long been recognized that children develop along several dimensions and with many influences (Department of Health (DH), 2000) and that there are key stages of development (Aldgate et al, 2006). There is an abundance of literature, which discusses the key stages of child development, attachment, resilience and parenting capacity.

In his popular work: Developmental Psychology Childhood and Adolescence, Shaffer (1989) describes development as: was clearly resilient. It is important to discuss adversity and resilience together as many authors have identified a clear link between adversity and resilience (Shaffer, 1989; Bowlby, 1998; Rutter, 1998; Lease, 2002; Ding and Littleton, 2005; Aldgate et al, 2006; Daniel et al, 2010).

‘The systematic changes in the individual between the moment of conception and the day one dies’ (Shaffer, 1989),

Again, these authors mainly present research that has been carried out in ‘western’ cultures. There is a theme in the literature that presents adversity as a negative influence. For example:

‘By three years of age children at higher risk of poorer outcomes can be identified by their chaotic home circumstances, their emotional behaviour, their negativity and poor development’ (Scottish Government, 2008b),

The clearly negative phraseology in this extract from the Scottish Government's publication The Early Years Framework (Scottish Government, 2008b) is indicative of a general theme of viewing resilience built up by children in adverse situations as negative. Challenging this view are Luthar et al (2000) who assert that resilience can be regarded as a ‘dynamic process encompassing positive adaptation within the context of significant adversity’, and Wolin and Wolin (1999) who assert that there is a clinical bias toward identifying pathology in affected children. The latter was research in relation to the children of alcoholic parents, but this raises the question of whether this exists, and whether it is a wider phenomenon.

The resilience the patient displayed in this case could have been because of poor parental attachment or adversity in childhood, or it simply could be that it is part of her cultural ecology and regarded as a positive attribute in her social structure. Whatever view of child developmental psychology, identity, independence of mind, adversity and resilience one takes, it must be assumed that the patient in this case had a clear sense of identity, displayed independence and was clearly competent enough to accept or decline any treatments offered. The Joint Royal Colleges Ambulance Liaison Committee (JRCALC) states that ‘valid consent to treatment is therefore vital to all forms of healthcare’ (JRCALC, 2006).

Quite apart from the legal element of informed consent, it is an essential part of inclusion and shared decision-making. It is important for young people to feel included (Scottish Government, 2008) and have shared decision-making (Scottish Government, 2010c), but circumstances like these also have to be taken into account during consultations. I also had to consider that I had a duty to act in the best interests of the child as set out in the Children (Scotland) Act 1995 (HMSO, 1997) and that under the terms of the The Age of Legal Capacity (Scotland) Act (HMSO, 1991), she was a competent child. This meant that she had the right to choose whether to decline any treatments and whether to include her parents in decisions affecting her health and well-being (in England and Wales, the best example of a similar framework is the Gillick Principle (Gillick v West Norfolk and Wisbeach Health Authority, 1986). It is also important to understand that a competent child must be allowed to make these decisions within their own ecology and to show respect for that ecology.

On further analysis of her interactions with her family and the ambulance crew, I have to consider that although she was outwardly polite, respectful and seemingly positive, she may have been displaying elements of an anxious avoidant insecure attachment disorder described by Daniel et al (2010). They assert that the primary care giver or main focus of attachment in situations like these can often appear cold and distant and the child is often rewarded by parental approval for independent, self-caring behaviours. This may explain why she declined pain medication and declined to be carried down the stairs by the crew. However, children and families should be valued and respected at all levels in our society and have the right to have their voices sought, heard and acted upon by all those who support them and who provide services to help them (UNCHR, 1989).

Conclusion

A child's interaction with a parent may be vastly different in differing cultures. In this case, communicating and sharing decisions with her father seemed to be her preferred and most comfortable way of familial interaction and decision-making. I considered that it may not be in her best interests to refuse pain medication and to walk down some stairs, but it seems I had been thinking about how I would act as a 14-year-old in my cultural ecology. In not confronting the apparent disempowerment, I had mixed feelings, but my approach enabled appropriate decision-making within the framework she was used to. This reduced the potential for increased stress in a situation, which was already upsetting for her and her family.

This also showed respect for cultural diversity and for the importance of her family in her social ecology. I was able to demonstrate an awareness of needs and risks (i.e. her need to show independence and to walk down the stairs, but also her need for medical attention and the low risk of exacerbating the injury). Her need for medical attention had to be balanced with her need for empowerment, inclusion, independence and the need to make health-related decisions within her social structure. There may be a question as to whether she declined pain medication completely independently, but with the cultural and language barriers in this case it is almost impossible to draw a firm conclusion.

There are many factors to consider when planning treatments and informing and enabling decision-making. Not least the age of the child (a child of 7 for example clearly would have different cognitive capacity than a 14-year-old) and the nature of the injury (minor injuries like this clearly require a different approach than major injuries). There are a number of implications for practice, for example: if proper evaluation of all of the circumstances of each situation does not take place then we may disempower young people or offend people from cultural backgrounds we are unfamiliar with. Did I seek this child's voice well enough on this occasion? I have come to the conclusion that this was her ‘social framework’ and it was right for her.

Action planning

If a similar situation arose in the future I do not think I would do very much differently, except consider discussing treatment options at a more opportune time, perhaps when the parent/s were not in the room. This would allow a child to assess the information and the options involved, including how much involvement parents should have in the subsequent decision-making. But I also have to consider whether this might cause disagreement amongst the family and upset to the child. With improved knowledge I would now feel more confident in discussing the wider issues around consent with a child of a similar age and in similar circumstances.

Confidentiality statement: all reasonable steps have been taken to ensure patient confidentiality. The nature of the injury sustained has been changed. The incident was at a location well outside my normal operating area. No country-specifc details have been included; instead the term ‘Asian’ has been used throughout. Some other details have been changed; these do not obvert proper refection.