LEARNING OUTCOMES

After completing this module, the paramedic will be able to:

If you would like to send feedback, please email jpp@markallengroup.com

In total, across all ages, places and causes, approximately 1% of the UK population dies each year (Office for National Statistics, 2010). Most people who are approaching the end of their life will be living in the community with chronic incurable disease (Office for National Statistics, 2009) and deteriorating health.

Ambulance crews may attend and provide care to these patients and their families for a variety of reasons. They may include care in response to a crisis; emergency care; and transportation between different settings (Munday, 2007; Ingelton et al, 2009). The complexity of care required and the frequency of encounters with these patients means that ambulance clinicians are vital to delivering high-quality end-of-life care to people in the community setting (National End of Life Care Programme, 2012).

The current article presents an overview of some of the key issues that impact upon the delivery of care by ambulance clinicians to patients at the end of life. By way of addressing these issues, the article then outlines an online education package in end-of-life care which was specifically designed for ambulance clinicians working within one ambulance service in the UK, in response to an analysis of their end-of-life care education needs (Pettifer and Bronnert, 2013).

Ambulance clinicians and end of life

There is little research or published data outlining the number of people who are known to be approaching the end of their life who are encountered by ambulance clinicians working in the UK. A survey across the West Midlands Ambulance Service demonstrated that attending to patients at the end of life makes up a significant part of the work: just over 33% of responders estimated that they are called to a patient who is terminally ill at least once in every shift, and a further 29% once every two to five shifts (Munday et al, 2011a).

Why might an ambulance be called?

Exactly why patients who are terminally ill or their families call an ambulance is not extensively discussed in the literature. As part of a broader study, Ingelton et al (2009) identified that urgent ambulance services were commonly dispatched to patients approaching the end of their life in response to a sudden change in their condition; a change in a carer's capacity to cope; and/or a perceived ‘threat to life’ assessments made by emergency call handlers and general practitioner (GP) out-of-hours service providers. This fits with the authors' own clinical experience.

When patients who are approaching the end of their life come into contact with ambulance clinicians, they may have one or many of a diverse range of issues. In addition to clinical needs, patients and families may be distressed; have particular preferences about how they wish to be cared for; and/or have difficulty accessing the care they need (National End of Life Care Programme, 2012).

Each of these has implications for ambulance staff who are aiming to provide quality end-of-life care. Additional issues such as obtaining relevant information about these patients, limited formal education and limited practice guidance in end-of-life care add to the complexity so that encountering patients at the end of life can be challenging.

It is beyond the scope of the present article to discuss all of these areas in depth; therefore, it will focus on the following key issues:

In response to each of these issues, the article will go on to describe an educational initiative that aims to equip ambulance clinicians in responding to calls from patients approaching the end of life.

Care in the last few days of life

Patients at the end of their life may have a variety of symptoms or urgent care needs. Pain, nausea/vomiting, agitation, breathlessness and terminal respiratory secretions are commonly experienced when a person is dying (Solano et al, 2006; Teunissen et al, 2007). Where possible, families and patients are made aware that these symptoms may develop, and steps are taken to ensure appropriate medication to treat each symptom is available in the person's home. Other urgent care issues may be less predictable. These include falls, overwhelming emotional distress and symptoms such as seizures or bleeds (Nauck and Alt-Epping, 2008).

How ambulance clinicians manage patients with urgent care needs will depend upon factors such as symptom severity, and what care the attending ambulance clinician is able to offer in a time-critical community situation. Care preferences and coordination of care also have an important impact on how urgent care issues are managed.

Care preferences

When patients have strong preferences about any aspect of their care, or when health professionals think it will help to plan and coordinate care, a formal record of the patient's wishes may be created. The National End of Life Care Strategy (Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC), 2008) supports this approach. One of the things that may be recorded, if it is important to the person, is their preference for place of care.

Documents about care preferences usually stay with the patients and form part of their care plan; they should ideally be available to all health professionals who care for, or may care for, these patients. The Mental Capacity Act 2005 requires clinical staff, including ambulance clinicians, to take these documents into account when making decisions about a person who no longer has the capacity to express his or her own wishes.

Appropriate place of care

The appropriate place of care for a person who is dying is determined based on a number of factors. This includes their own preferences; their clinical needs; and the organisational capacity to provide their care in a particular setting such as community, hospital or hospice (Murray et al, 2009).

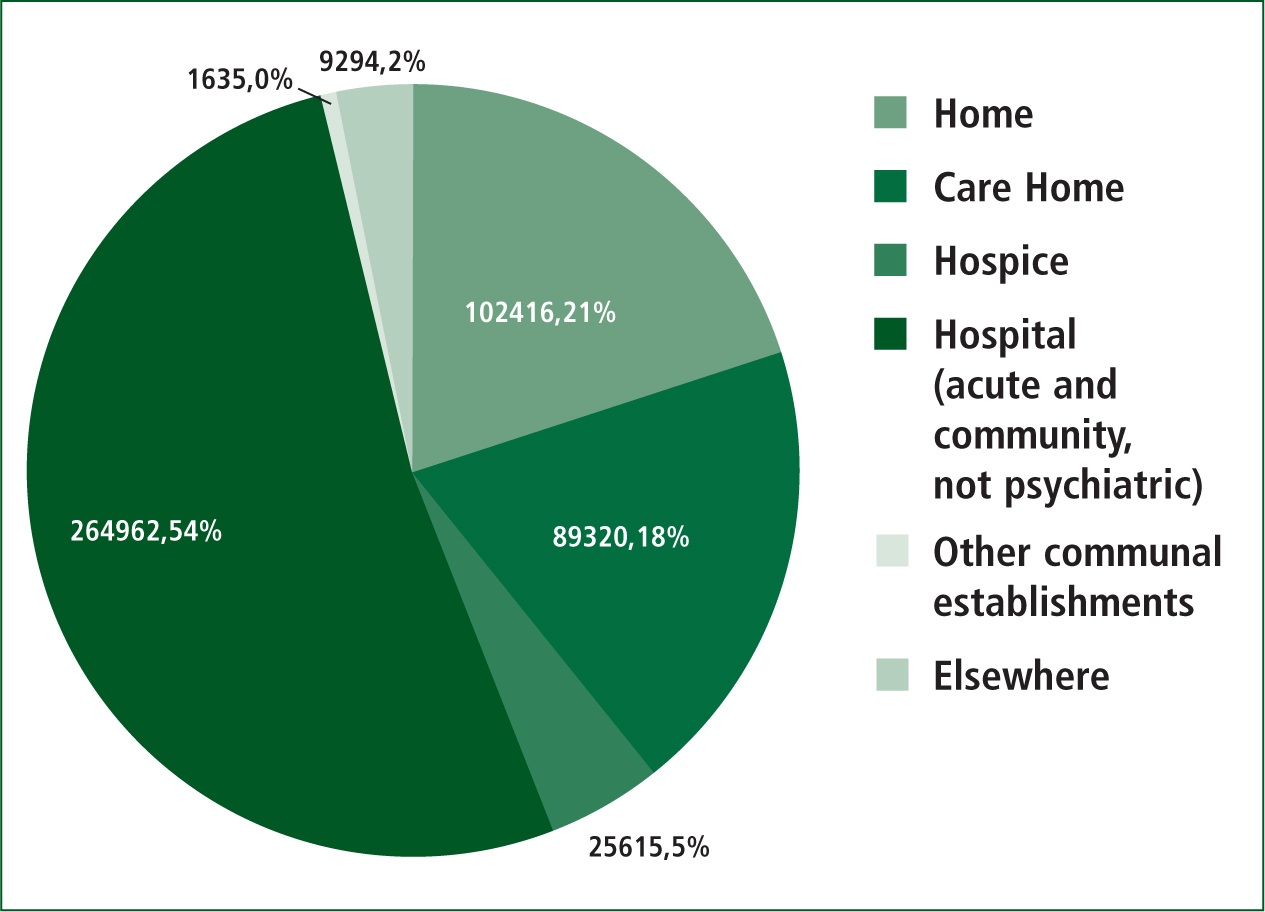

Research has established that the majority of people would prefer to die in their own home providing they can be cared for adequately (DHSC, 2008; Higginson, 2009). Despite this preference, however, the majority die in hospitals (Gomes and Higginson, 2008; National End of Life Care Intelligence Network, 2008–2010). Figure 1 outlines the place of death of people in England and Wales.

Preferred vs. actual place of death

The reasons for the discrepancy between preference and attainment of place of death are complex. Predicting when somebody will die is inexact. Some patients may deteriorate suddenly or more quickly than health professionals may anticipate (Gadoud and Johnson, 2011); other people change their preferences for care options as they deteriorate (Everhart and Pearlman, 1990).

Factors which have been found to increase the likelihood of a patient dying at home include the frequency of healthcare provision in the home; informal carers living in the home; and access to other informal support beyond it (Gomes and Higginson, 2008). Given the complexity and limited maneuverability of many of these factors, it may not always be possible for the primary healthcare team to have optimal end-of-life care in place to enable patients to be cared for at home.

Place-of-care decisions

For ambulance clinicians, decisions about place of care usually revolve around whether or not to transport the patient to another care setting. Although research is sparse, it tends to suggest that ambulance clinicians commonly transfer patients at the end of their life to hospital.

Seale and Kelly (1997) and Munday (2007) found that many hospitalised patients at the end of their life were admitted following unplanned emergency contact with the ambulance service. Furthermore, Seale and Kelly (1997) found that 33% of patients with cancer who died in hospital had been admitted as a result of a 999 call. In response to a hypothetical scenario involving an acutely unwell terminally ill patient, 64% of responding ambulance clinicians indicated they were likely to transport the patient to hospital (Munday et al, 2011a). Clinical factors, and whether appropriate support for the ambulance clinicians and/or patients and their families is available, will heavily influence decisions about transport. A patient's preferences should also be taken into account. In some cases, unwanted transfer may be avoidable if care needs can be met in the home.

Coordination of care

Assessing end-of-life care urgently at home

The number of multidisciplinary health professionals involved in the care of a dying person can be considerable. For example, a patient dying of cancer may have regular encounters with a palliative care clinical nurse specialist, community staff nurse, GP, oncologist, occupational therapist and social care professional. Coordination of care is an important challenge for health care.

Quality standards from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) emphasise that nominated informal carers of people who are known to be approaching the end of life should have information about how to access urgent care in the event of a crisis at any time of day or night (NICE, 2011). However, in a crisis situation, not knowing or remembering who to contact, or how to access their help quickly, may be very frightening for some patients and relatives. It is usually more difficult to access professionals who are familiar with the patient's situation outside of normal working hours because primary care and specialist end-of-life care services often operate a reduced service (DHSC, 2008). Consequently, because of the memorable number and rapid response, an ambulance may be called instead of contacting other professionals (National End of Life Care Programme, 2012). This means that ambulance clinicians become frontline responders to issues relating to end-of-life care.

Improving access to information

Prompt access to information about a patient en route or soon after arrival on scene may help ambulance clinicians when they are making decisions about care for patients. However, integration and coordination of care across different health and social care organisations is often weak (DHSC, 2008).

Patients and families may not realise that ambulance staff usually have limited access to information about the condition of the patient in advance of arrival on scene. It may be distressing for all involved if ambulance clinicians are not aware of decisions that have been made in conjunction with other health professionals, e.g. care planning or do not attempt cardiopulmonary resuscitation (DNACPR) decisions. Fortunately, there are initiatives at local and national level, which aim to improve access to information and coordination of care for patients who are approaching the end of their life (Cheung and Riley, 2012; National End of Life Care Intelligence Network, 2013).

Accessing specialist support

The variability of specialist end-of-life care services in different areas (West Midlands End of Life Clinical Pathways Group, 2009) and the number of professionals involved in delivering end-of-life care both pose difficulties for ambulance clinicians responding to a call. Unless ambulance clinicians are familiar with the services available and their referral criteria, or they can obtain this information quickly, it will remain difficult to access the advice and support from other professionals that they and the patient may benefit from.

End-of-life care education project

In 2009, the West Midlands End of Life Care Clinical Pathways Group identified that enhanced primary care services operating outside of normal working hours, stronger integration and coordination of care across different health and social care organisations and education and training could potentially enable more people to achieve their preference of dying at home. While some local initiatives to develop and deliver education to ambulance clinicians have occurred (Callaghan and Ford-Dunn, 2010), end-of-life care education in the national ambulance curricula is minimal.

In recognition of the challenges that ambulance clinicians face, the West Midlands Strategic Health Authority funded a collaborative project led by Coventry University to develop education in end-of-life care. The project group was made up of representatives from two universities, an ambulance service and a local hospice.

The end-of-life care education project for ambulance clinicians was conducted over five phases:

Education needs analysis

A multifaceted education needs analysis was carried out. Current literature concerning end-of-life care delivered by ambulance clinicians was reviewed. Although studies have concluded that further education in end-of-life care is required (Wiese et al, 2009; 2012), no detailed published literature considering the end-of-life care educational needs of ambulance clinicians was found.

Consequently, a survey was undertaken to provide an evidence base of the educational needs of ambulance clinicians. A survey of ambulance clinicians across one NHS Ambulance Trust was carried out to provide an evidence base. This established that end-of-life care is a significant part of their workload and that the majority of ambulance clinicians did not feel confident in their knowledge and skills in clinical management of terminal care (Gakhal et al, 2011).

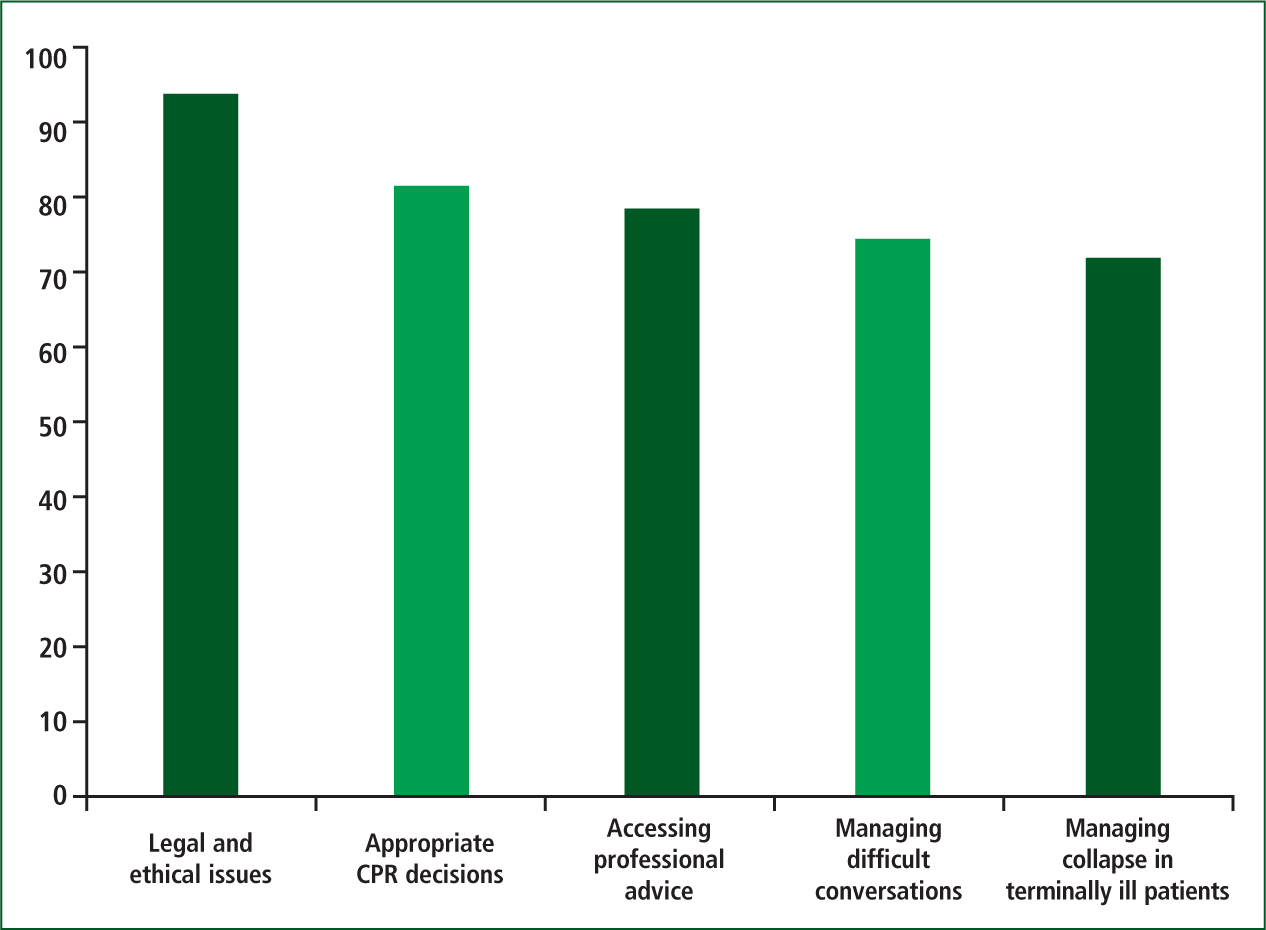

Areas of training most welcomed were: legal and ethical issues (94%); appropriate CPR decisions (80.7%); accessing professional advice (79.5%); managing difficult conversations with patients and relatives (74.7%); and managing collapse in terminally ill patients (72.3%). Training in clinical symptom management—a mainstay of palliative care practice—was rated as less welcome (Gakhal et al, 2011) (Figure 2).

Beyond the literature review and survey of educational needs, consideration of relevant local and national policy and the clinical and educational experience of key advisors added to the needs analysis. The key advisors included practising ambulance clinicians, palliative care medical and nursing staff and a GP.

Educational initiative

An online learning package based on four fictitious cases, which consider pertinent issues in a user-friendly way, was developed. The education includes:

Each case takes approximately 40 minutes to complete. Sources of further reading are given and students can download a certificate of completion on successfully meeting the learning outcomes. Table 1 shows an outline of the cases and associated learning objectives that comprised the education package. The education became mandatory for all ambulance staff in an independent decision-making role working in the target NHS Ambulance Trust (Pettifer and Bronnert, 2013).

|

1. Mr and Mrs Johal

|

|

|

2. Edith Webb

|

|

|

3. Mrs Bates

|

|

|

4. Jo, Mark and Ellie Harding

|

|

Evaluation

Preliminary evaluation of the education was positive, with 71% of students strongly agreeing or agreeing that the education would change their practice. Similar numbers indicated their confidence in delivering end-of-life care improved (Pettifer and Bronnert, 2013).

The level of detail was ‘about right’ for 65% of students with an approximately even number of the remainder considering the level of detail too little or too great for their learning. Some students found the online tool overly text-based and issues of access to study time and computers arose. However, 67% students reported positive overall satisfaction with the learning tool.

Students' comments indicated that they would value follow-up face-to-face teaching to discuss the issues raised in end-of-life care, paper reference materials to act as ‘aide memoirs’, and practical reference materials. A separate project led by Warwick Medical School has piloted a decision support tool for ambulance clinicians (Munday et al, 2011b).

Accessing relevant of end-of-life education

Sources of education about end-of-life care can be found on the End of Life Care for All (e-ELCA) section of the national e-Learning for Healthcare (2018) website. The learning packages hosted here are designed to be relevant to all clinical staff engaged in delivering end-of-life care. Ambulance staff can register to access the learning materials, which include modules in advance care planning and communication, and relevant case studies.

Conclusions

When patients are approaching the end of their life, they and their families are likely to have a range of needs. Urgent issue management and care preferences including place of care and coordination of care are important and relevant to ambulance clinicians who may be required to deliver care to a patient approaching the end of their life. An educational initiative specifically designed for ambulance clinicians has been developed. It is hoped that this will equip ambulance clinicians with increased knowledge about end-of-life care, and that this will enhance their practice and positively influence the care of those at end of their lives who are living in the community.