Gout. The very name often conjures images of an elderly, rather stout, port-drinking gentleman of the upper classes. Gout has a tendency to affect men more than women, and some myths still linger around it. Such myths focus on gout being largely an affliction of wealthy, obese men, and this article aims to dispel thesemyths surrounding the increasingly common and debilitating condition. The article will present a historical and physiological background to gout prior to addressing the presenting symptoms. It will then outline a potential framework for pre/out-of-hospital assessment and management of gout, based on the latest evidence, while also outlining a background to the condition, its incidence and aetiology.

Gout is a condition that may not initially appear to be significantly relevant to paramedic practice; however, by providing a comprehensive overview to this misunderstood and very painful condition, it will become clear that the paramedic can play a significant role in the care of patients presenting with an acute gout attack.

Background to gout

While gout is becoming an increasingly prevalent condition, it has its background many thousands of years ago. The Egyptians first identified gout in 2 640 BC, and in the fifth century, Hippocrates rather aptly referred to gout as the ‘unwalkable disease’. The presenting symptoms of gout remain unchanged, and evidence suggests that the common treatment in past millennia was an alkaloid derived from the autumn crocus (Colchicum autumnale). This drug is still used today, although it is perhaps better known by its current name, colchicine. Colchicine was initially used as a purgative in ancient Greece, but was not administered specifically for gout treatment until the sixth century AD by the Christian physician Alexander of Thralles (Nuki and Simkin, 2006).

What is gout?

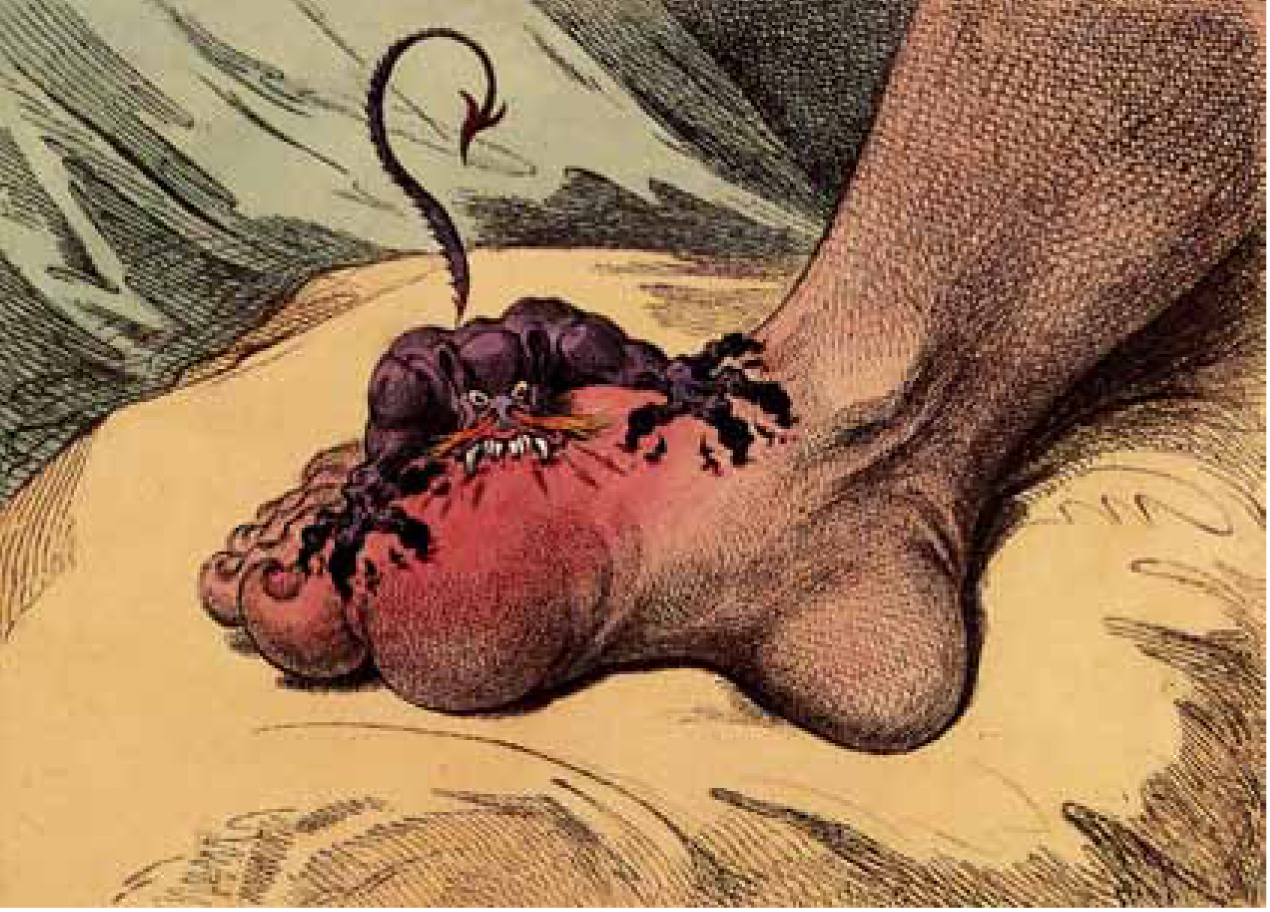

Gout is a very painful and common form of acute arthritis, which is becoming increasingly prevalent in many Western societies. The arthritis (joint inflammation) associated with gout is caused by a disorder of the body’s purine metabolism, resulting in raised serum uric acid level, known as hyperuricaemia, and the subsequent deposition of the urate crystals in joints and soft tissues. The famous image of gout, from a 1799 caricature by James Gillray (Figure 1) gives the reader an idea of the acuteness of the arthritis and key affected joint.

The word ‘gout’ is derived from the Latin word ‘gutta’, which literally means ‘to drop’, as it was believed in the 13th century that the poison dropping into affected joints caused gout (Suresh, 2005). Although gout has been a diagnosed disease for many millennia, there remains gaps in clinical knowledge in relation to its treatment and management. Some of the causative factors for gout are well established, e.g. the tendency for gout to affect the older population, particularly obese patients and others with rather negative lifestyle habits, such as a high alcohol intake (Underwood, 2006). Over the centuries, the lifestyle of excessive alcohol intake, a diet of rich foods and subsequent obesity were reserved exclusively for those able to afford such luxuries—namely the wealthy and socially important—and therefore this was originally a disease exclusive to the upper social classes, supporting some of the myths surrounding this disease. Historical texts suggest that Henry VIII and Alexander the Great both suffered from gout, the former probably as a result of his love of rich foods and excessive alcohol intake.

Epidemiology

In the UK, gout is estimated to affect 1% of the population—usually men aged over 45 years. While this incidence rate may not initially appear significantly high, it is worth noting that Parkinson’s, coeliac disease and schizophrenia have similar rates of incidence in the UK. The incidence rate of gout increases with age, with a 7% rate reported in men aged over 65 years. Gout is predominantly a male disease, particularly in the under 65 years age group. However, gout also affects woman to a ratio of 1:4 (female to male), and in the 65 years age group and over, this ratio drops to 1:3. The reason for this gender difference is not fully understood; however, research suggests that oestrogen lowers serum urate levels but serum urate levels can rise after menopause (Dirken-Heukensfeldt et al. 2010).

Aetiology

Gout is an ancient and common form of inflammatory arthritis, and is the result of the deposition of uric acid crystals in tissues and fluids within the body. This deposition is sometimes referred to as ‘podagra’ or ‘gouty arthritis’ and results from the overproduction or the under secretion of uric acid (Centre of Disease Prevention and Control, 2011).

In an overproduction of uric acid crystals, the crystals deposit in the joints when the bloodstream becomes saturated with urate, a condition known as hyperuricaemia. Hyperuricaemia is therefore the imbalance between the production and excretion of urate either from urate underexcretion, overproduction or both. Underexcretion of urate is the most common cause of hyperuricaemia, accounting for 80–90% of gout cases. Hyperuricaemia may also be triggered by an excessive breakdown of cells and a subsequent build up uric acid crystals—sometimes referred to as monosodium urate crystals (MSU). These crystals become deposited in the tendons, joints, occasionally the kidneys and other organs, and it is this deposition of uric acid crystals that leads to gout (Centre of Disease Prevention and Control, 2011). A rather unusual anomaly of gout is that patients with hyperuricaemia may never suffer from gout and some gout patients never suffer hyperuricaemia. The reason for this is not entirely clear.

Purines

Purines play an important role in gout and it is worth outlining this in more detail. Purines are natural substances, found in virtually all foods and as they form part of our genetic chemical structure, including all plants and animals, purines are therefore hard to avoid in any diet. However, purines are also produced naturally when our body cells die and are completely metabolised as uric acid. Our bodies do require purines to help prevent damage to blood vessel linings and therefore a continuous supply of purines is vital for our cardiovascular systems. Although higher purine intake may play a part.

Uric acid

Uric acid also plays an important role in gout, the end result of the purine metabolic pathway. All mammals (except higher primates such as humans) express uricase, which is an enzyme that converts uric acid to allantoin and as a result, humans have higher urate levels than other mammals. The evolutionary loss of this uricase gene in humans is thought to potentially impact on blood pressure control and some metabolic syndromes, although this is still debated (So, 2008). However, recent research in epidemiological and animal studies would suggest that hyperuricaemia has an important role in hypertension and metabolic syndromes. Some studies have also linked the excessive consumption of fructose to hyperuricaemia and metabolic disorders (Nakagawa et al. 2005). There is an established link between hyperuricaemia and cardiovascular diseases; hypertension is one of the most common comorbidities of gout (Choi et al. 2012), while hyperuricaemia is an independent risk factor for the development of hypertension (Feig et al. 2006).

Hyperuricaemia

Hyperuricaemia, or raised uric acid levels, can therefore be influenced by a number of factors such as genetics, diet and metabolism (Table 1).

| Diet | Medication | Diseases | Other factors | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factors increasing serum uric acid levels |

|

|

Those increasing purine turnover: |

|

| Factors decreasing serum uric acid levels |

|

|

Presentation: acute attacks

Gout has a rapid onset, usually presenting as an acute inflammation of a single joint, often waking the patient from sleep (Suresh, 2005; Underwood, 2006). In more than 70% of gout patients, the most commonly affected joint is the first metatarsophalangeal (MTP) or big toe joint, sometimes referred to as ‘podagra’ (literally meaning ‘foot catch’). However, other joints can also be affected and include the mid-foot (25–50%) and the ankle (18–60%) (Roddy et al. 2007). Larger joints such as the knee, wrist, finger and elbow joints are also potential gout sites since uric acid crystal deposition tends to occur in cooler aspects of the body (Suresh, 2005). Gout usually presents when the serum is saturated with uric acid—serum urate levels are at a concentration of 430 mmols/L for adults males and 360 mmols/L for adult females.

However, Underwood (2006) warned that asymptomatic hyperuricaemia is also common and that only a minority of patients with hyperuricaemia develop gout. As paramedics and other pre-hospital practitioners currently have limited access to point-of-care testing or the ability to collect and request laboratory testing, this may appear to be a mute point. However, it is useful to have some level of knowledge to educate and advise patients, suggesting that they are assessed for their uric acid levels at some stage.

There are two key presenting symptoms in gout: pain and arthritis, which will often occur simultaneously.

Pain

One of the key presenting symptoms of gout is the sudden onset of severe, acute pain in a single joint, or a monoarthritis. Patients will often describe the pain as ‘excruciating’ or ‘unbearable’, to the extent that even the weight of a bed sheet on the affected joint is intolerable. The pain is usually very localised over the affected joint, with virtually little or no pain reported in surrounding areas. Pain usually presents rapidly, taking as little as 24 hours from the first symptom of slight joint soreness or stiffness to the peak of the attack. Although the cause of the severity of the pain in gout is not fully understood, recent research suggests that the urate crystals provoke an inflammatory response from leucocytes and synovial cells, which trigger the release of cytokines that further intensify the local inflammatory reaction, and may therefore be the cause of such intense pain (So, 2008; Busso and So, 2012).

Arthritis

The second key gout symptom is arthritis, or joint inflammation. Gout-affected joints will appear erythematous, warm/hot to touch, often with some associated oedema, with pain reported on passive movement. As the joint will be exquisitely painful to touch, the best approach is to observe rather than attempt to palpate the joint if at all possible—the patient will be unlikely to let you do anything else.

The key joints affected are:

Pyrexia

Patients may also present with a pyrexia (core body temperature over 37.5°C), particularly if more than one joint is affected. However, pyrexia is not always a presenting symptom and can indicate other joint conditions (see Differential diagnosis).

Risk factors

Although some studies have identified a genetic link for hyperuricaemia-linked diseases, this only accounts for a small fraction of cases related to hyperuricaemia and gout (So, 2008). As with most long-term or chronic conditions, lifestyle plays a role in some of the risk factors. The European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) produced evidence-based guidelines in 2006, identifying the following risk factors for gout (Table 2).

| Male gender |

| A diet that is rich in meat and seafood |

| Alcohol, particularly beer and spirits (10 or more grams per day) |

| Diuretic therapy |

| Obesity |

| Hypertension |

| Coronary heart disease |

| Diabetes mellitus |

| Chronic renal failure |

| High triglycerides |

| Chemotherapeutic drugs |

| Joint morbidity and trauma. Previous disease and joint is affected injury may infuence which joint is affected |

Older patients may also develop oligoarticular or polyarticular gout—gout affecting several joints. Although such presentations are less painful, the gout can affect joints already affected with osteoarthritis, further complicating diagnoses (Suresh, 2005).

Phases in gout

The natural history of gout presents in three distinct phases:

Tophi in gout is usually best visualised via computerised tomography (CT) scanning and is the deposition of urate crystals in the synovial capsule. Although generally painless, tophi can trigger local inflammation (Burns and Wortmann, 2012). Initially considered an unimportant feature of gout, the ability to detect and measure gouty tophi will provide objective assessment of tophus size, thereby improving disease and treatment monitoring (So, 2008).

Diagnosis

The diagnostic features of gout are outlined in Table 3 below.

|

Previous attacks

|

|

Age of onset:

|

|

Possible risk factors for developing gout:

|

|

Associated comorbidity:

Hypertension Renal impairment Diabetes mellitus Myeloproliferative disease, e.g. disease of the bone marrow Hyperlipidaemia (especially hypertriglyceridaemia) Vascular disease Severe psoriasis Enzyme defects, e.g. hypoxanthine guanine phosphoribosyltransferase (HGPRT) deficiency and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6Pd) deficiency |

Assessment of gout

History, observation and palpation

From a paramedic perspective, the assessment of a suspected attack of gout will be the traditional approach of taking a history of the presenting symptoms (acute onset of pain and monoarthritis) and including the patient’s past medical history (PMH), which may provide further information relating to any previous attacks of gout. This may have been several months, or even years, previously. Recording and documenting the patient’s blood pressure, even if a negative history of hypertension is reported, and also a comprehensive list of any current medications (prescribed and otherwise), will be useful. Observation will probably be the key mode of assessment; as detailed earlier, such is the intensity of pain, that palpation directly over the affected joint will be best avoided. However, remember that, specific to gout, the surrounding joint area (usually equivalent to a 50 pence piece size) outside the joint may well be (gently) palpable. Observation will usually be a foot that is already exposed (hobbling patients wearing flip flops in winter is a good sign) and remember that patients are often unable to bear even the slightest pressure. The joint will be inflamed, erythematous, maybe with some oedema (Figure 3).

Joint fluid microscopy and culture

For the definitive diagnosis of gout to be established, the gold standard approach is the aspiration of the affected joint or tophus with the confirmed identification of MSU crystals (Burns and Wortmann, 2012). However, aspiration of joint fluid is not indicated unless there is doubt regarding the diagnosis of gout or a septic arthritis is suspected. Obviously, joint aspiration in the acute phase would be an invasive and painful procedure, undertaken under local anaesthesia by an appropriately qualified practitioner. The presence of urate crystals in the aspirate would confirm the diagnosis of gout and the absence of evidence of white blood cells would rule out a septic arthritis.

A Clinical Knowledge Summary (CKS) review rated the quality of evidence supporting the use of microscopy to detect urate crystals as ‘bronze’ (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, 2012). The bronze standard relates to no randomised controlled trials (RCTs) being established and/or reported on the effect on clinical outcomes for testing for urate crystals in synovial fluid or tophus. This particular test can have false positives and false negatives, and the quality of the test depends on the quality of both the laboratory providing the test and the specimen itself (Schlesinger and Schumacher, 2004). Clearly this is not a procedure that would be undertaken by a paramedic, but does provide some useful clinical information for the patient, particularly if there is some doubt regarding a gout diagnosis.

Serum uric acid or plasma urate

The serum uric acid (SUA) is usually measured 4–6 weeks after an acute attack of gout to confirm hyperuricaemia. In the UK, the upper limit of the reference range is usually taken as 140–360 mmol/L for males and 200–430 mmol/L for premenopausal females (Pathology Harmony Group, 2011).

However, this laboratory result may not necessarily be helpful as hyperuricaemia may be present without gout; this is a particularly common feature during the acute attack, when plasma urate levels initially fall. Equally (and as a rather odd anomaly of gout), the presence of hyperuricaemia does not necessarily equate to a gout diagnosis, since most people with hyperuricaemia may not ever develop clinical gout (Burns and Wortmann, 2012). In addition, further laboratory testing for renal function, cholesterol levels and fasting blood glucose may be appropriate if clinically indicated, particularly if there are concerns regarding some of the risk factors (Table 3).

Treatment for gout

Without specific treatment, an acute presentation of gout usually resolves spontaneously within 7–10 days. After an initial acute attack, patients may be free of symptoms for months, or even years. Patients developing recurrent attacks of gout may also be symptom-free for varying time periods between attacks, referred to as Phase 2 (or the ‘intercritical’ period). Gout attacks can also increase in both frequency and severity, affecting different joint sites, becoming monoarticular (one joint) or polyarticular (several joints). Some patients may go on to develop more frequent gout attacks, a few eventually developing chronic tophaceaous gout or permanent joint damage, or both, often referred to as Phase 3 (Roddy, 2011).

Pharmaceutical treatment

Gout is a self-limiting condition; however, due to the level of pain, the aim of therapeutic treatment is to reduce pain and hasten recovery. Anti-inflammatory agents are the initial key drug of choice, and should be commenced as soon as possible to suppress the acute inflammation (Suresh, 2005, Zhang et al, 2006; Burns and Wortmannm, 2012). The key analgesic options are available for paramedic or paramedic practitioner administration via the Joint Royal College Ambulance Liaison Committee (JRCALC, 2006), although not all treatments are currently available to paramedics. However, this may be useful clinical information for both practitioner and the patient.

The key therapeutic treatment options for gout are: l Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

NSAIDs

NSAIDs (such as aspirin, ibuprofen, indomethacin and naproxen) can be administered by paramedics (as per local and/or national guidance) provided there are no contraindications, e.g. known hypersensitivity or allergy, renal impairment, active gastric ulcer disease, congestive cardiac failure or anticoagulant therapy. NSAIDs work by blocking the production of prostaglandins. Prostaglandins are chemical messengers responsible for the pain and swelling in a range of inflammatory conditions. In an acute attack of gout, paramedics are able to administer ibuprofen for the first-line management of pain, as outlined in the JRCALC guidelines for the management of pain in adults (JRCALC, 2006).

Cyclo-oxygenase-2 (COX 2) inhibitors are specific NSAIDs that reduce the risk of gastric ulceration, which is a common side effect of traditional NSAIDs. Cox 2 inhibitors target the enzymes responsible for inflammation and pain, and include drugs such as celecoxib and rofecoxib, although some gout patients may be at higher risk of side effects from the traditional NSAIDs or COX-2 inhibitors (Underwood, 2006).

Colchicine

As referred to earlier, colchicine is a very old drug, but nonetheless remains a very effective treatment in acute gout. Colchicine works by inhibiting the acute inflammatory response, such as inhibiting neutrophil adhesions, motility and mast cell histamine release, which are thought to contribute to the inflammatory response in gout (Suresh, 2005; Burns and Wortmann, 2012).

Colchicine is a prescription only medicine (PoM), which should be prescribed at 0.5 mg or 0.6 mg (500–600 mcg) hourly until symptoms subside and/or nausea, vomiting and diarrhoea develop. The failure for symptoms to respond to colchicine can rule out the diagnosis of gout. However, due to the commonly occurring and rather unpleasant side effects of colchicine, dosing at 2–6 hours has been demonstrated to reduce these side effects, which can often be difficult to endure in association with acute pain in a condition also limiting mobility, and should be prescribed in lower doses in patients with renal insufficiency (Suresh, 2005; Burns and Wortmann, 2012). However, these dosing regimes vary depending on the practitioner, and the recommendations for colchicine dosing acts as a guide, based on patient and practitioner past experience (Zhang et al, 2006). Patients who have suffered previous gout attacks may already have a colchicine supply prescribed for any future attacks occurring out of hours and it may be worth checking if the patient has a current colchicine supply available (check the drug is in date before administration).

Intra-articular corticosteroids

Although intra-articular corticosteroids are not currently prescribed or administered by paramedics for gout, it is useful to have a brief overview of the role of these drugs for clinical awareness and for patient information/education.

Intra-articular corticosteroids are administered to patients where medium-size joints (e.g. wrists or elbows) to larger joints (e.g. knees or ankles) are affected, and in the confirmed absence of septic arthritis. Intra-articular steroids may also be administered if a patient is unable to tolerate NSAIDs or colchicine. The dose is 40 mg for medium-sized joints and 80 mg for large-sized joints, and pain relief is anticipated within 24–48 hours (Suresh, 2005).

Systemic corticosteroids

In patients with polyarticular gout (where many joints are affected) or in severe cases of gout, systemic corticosteroids may be prescribed. A single dose of methylprednisolone 80–120 mg is effective or a divided dose of 20–40 mg/daily initially; reducing the dose over 10 days to prevent any rebound attacks is recommended. Even a ‘short, sharp’ courses of corticosteroids can impact on blood pressure and blood glucose control, and patients should ideally be monitored for both blood pressure and serum glucose and provided with a steroid ‘blue card’ to inform other health care professionals of the patient’s current corticosteroid drug therapy. Some paramedic practitioners may have the ability to administer systemic corticosteroids in a range of conditions.

Prophylactic treatments

Gout is a recurrent disease; 62% of patients experience a recurrence within one year, 78% within two years and only 7% of patients have no further episodes for 10 or more years (Suresh, 2005). Prophylactic treatments are often prescribed to patients with frequent attacks of gout, chronic tophaceaous gout and with radiological appearances of erosion. Prophylactic medication should be commenced three to four weeks following the acute episode, to prevent prolonging any acute attack. The drug group of choice is the hypouricaemic drug group, that is aimed at reducing the serum urate concentration.

As 90% of gout patients underexcrete urate and less than 10% overexcrete, the two most commonly prescribed drugs are xanthine oxidase inhibitors, which reduce uric acid production, e.g. allopurinol, and uricosurics, which increase urinary uric acid excretion, e.g. probencid and sulphinpyrazone (Perez-Ruiz et al. 2002).

Allopurinol, rather than uricosurics, is almost always prescribed as a prophylactic agent as it lowers the uric acid levels in all patients, can be given in one daily dose, and is comparatively safe. Allopurinol is commenced at a lower dose (100 mg/day) and is increased over several weeks (up to 600–900 mg) to slowly lower urate levels and avoid acute attacks.

Colchicine can also be prescribed at a 500 mcg dose twice daily as a preventative measure. NSAIDs may also be prescribed as a prophylactic measure until at least four weeks following the serum urate levels returning to their normal levels (Suresh, 2005).

This medication information is useful for paramedics and paramedic practitioners and therefore can have a vital role to play in patient compliance.

Non-therapeutic treatments

Patients presenting with recurrent gout attacks usually do so as a result of poor compliance with prophylactic treatment and/or lifestyle risk factors and some of the key risk factors (previously outlined in Table 2) can be addressed by paramedics and pre-hospital practitioners. A large retrospective study over a 12-year period of almost 50 000 males reported an increased risk of gout in patients whose diets were rich in beef, pork or lamb and seafood. Choi et al (2004) reported a lower incidence of gout in patients with a high consumption of low-fat dairy products. A smaller more recent study by Zhang et al (2012) supported this theory, concluding that acute purine intake increased the risk of recurrent gout attacks almost fivefold among existing gout patients. The avoidance or reduction of purine-rich foods, particularly of animal origin, appeared to reduce the incidence of gout attacks.

Diet

The key dietary aim of gout patients is the reduction of purine-rich foods. However, a rigid purine-free diet is largely unpalatable, impracticable and difficult to maintain, since purines are found in most foods. Choi et al (2004) demonstrated that while purines derived from meat and fish clearly increased the risk of gout, the plant-originated purines failed to increase gout attacks.

In a case of severe or advanced gout, dietitians will often ask individuals to decrease their total daily purine intake to 100–150 g. A 3.5 ounce (or 100 g) serving of some foods can contain up to 1 000 mg of purines, including some of the foods outlined in the Table 4.

| Foods with very high purine levels (i.e. up to 1 000 mg of purines per 3.5 ounce/100 g serving) |

Meat:

|

| Foods with high and moderately high purine levels (5–100 mg per 3.5 ounce/100 g serving) |

Meat:

|

Alcohol consumption is also an important factor in gout. Excess alcohol intake can exacerbate hyperuricaemia, and chronic alcohol ingestion also stimulates purine production. In particular, beer contains high levels of purine, more than spirits and wine, and the evidence also suggests that patients consuming alcohol tend to be less compliant with their medications (Choi et al. 2004).

Management of gout

The British Society for Rheumatology (BSR) has published some useful guidelines for gout management in the UK (summarised in Table 5). The BSR guidelines have been included since they may be a useful tool on which to base local paramedic clinical guidelines. This guidance proposes that the paramedic’s management approach would be:

| Rest affected joints and commence immediate anti-infammatory drug therapy. Continue for 7–14 days |

| Administer fast-acting oral NsAids at maximum doses where there are no contraindications (e.g. patients with increased risk of peptic ulceration, bleeds or perforations, who should also be prescribed gastro-protective agents) |

| Colchicine is an effective alternative (but slower to work than NsAids) and provided at doses of 500 mcg twice daily, every day, to avoid side-effects |

| Allopurinol should not be commenced during an acute attack. Patients already taking allopurinol should continue dose (treat acute attack conventionally) |

| Opiate analgesics can be administered as adjuncts |

| Corticosteroids are very effective in acute gouty monoarthritis (by any route) |

| Corticosteroids can be effective in patients unable to tolerate NsAids and other treatments |

| Hypertensive patients on concurrent diuretic drugs should be prescribed alternative antihypertensive agents |

| Patients in cardiac failure should remain on diuretic therapy |

As outlined in the treatment section, the paramedic could administer a NSAID in addition to an opiate (which may be appropriate in severe cases and/or if the patient is in extreme pain) as per JRCLAC guidelines (2006). In addition, rest and elevation of the affected joint can prove very useful. If this is the patient’s first attack of possible gout, the patient will require urgent referral to a GP for further treatment and management, including a prescription for colchicine and possible oral corticosteroids as required.

Gout commonly presents in the primary care setting, and this primary care management of patients is in an increasingly large aspect of paramedic practice. This has been recognised and reflected by many of the UK’s universities, who now offer foundation and first-level degrees and various programmes of study in minor illness and injury. These are valuable educational packages since these ‘minor’ and non life-threatening or urgent conditions are often the ‘bread and butter’ of everyday paramedic clinical practice. This article therefore aims to highlight just one of these conditions, with the objective sharing the latest information and evidence to a wider audience.

Imaging in gout

An X-ray of an affected joint (especially wrist or knee) to observe for chondrocalcinosis (calcification of cartilage within joints, which can be associated with gout) is useful (Bencardino and Hassankhani, 2003). Signs of swelling within a joint on X-ray, combined with observed asymmetric swelling on examination, can also be indicative of gout. This is useful information, as some paramedic practitioners may have the ability to request radiological imaging.

Ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in gout have more recently been used to identify and manage patients with long-term gout; however, further studies are required to assess their usefulness in the diagnosis and management of gout (So, 2008).

Differential diagnosis

As gout is an acute form of arthritis, the presenting symptoms can appear similar to a range of other conditions, and should be considered in the differential diagnosis. The two key conditions to be considered as a differential diagnoses are an infectious arthritis, such as septic arthritis, or other crystal-induced synovitis, such as pseudogout (Burns and Wortmann, 2012).

Septic arthritis

Septic arthritis must be considered in any person who is systemically unwell (with or without a pyrexia) and an acutely painful, hot, swollen joint, particularly when other joints apart from the MTP joint are affected (e.g. a larger joint such as knee or ankle). Gout and septic arthritis can co-exist and it is important to diagnose septic arthritis promptly, as late recognition can be fatal. If septic arthritis is suspected or a gout diagnosis is at all unclear, always refer to the appropriate emergency department swiftly for emergency joint aspiration and culture (Suresh, 2005).

Pseudogout

Pseudogout is also known as calcium pyrophosphate deposition disease (CPPD) and is characterised by elderly onset, and a predilection for knees and wrists (Suresh, 2005).

Potential complications of gout

The most common complication of gout relates to tophaceaous joints. Tophi may create problems with activities of daily living, particularly in an older person when joints become inflamed, exude tophaceous material, or develop secondary infection.

Other complications, sometimes referred to as ‘gout comorbidities’, are frequently linked with gout, including diabetes, hypertension and renal insufficiency (Puig et al, 1991). However, hypertension and diabetes have a greater prevalence in female gout patients (Meyers and Monteagudo, 1986). Renal insufficiency also appears to be a predominately female gout-associated disease, particularly in post-menopausal women (Harrold et al, 2006).

Conclusions

Gout is a common form of acute arthritis that presents as an acute inflammatory arthritis, predominantly in the MTP joint. Gout is a disease largely affecting men under 65 years of age and is caused by the build-up and deposition of uric acid crystals in the joints, occurring when the bloodstream becomes saturated with urate—a condition known as hyperuricaemia. Hyperuricaemia is essentially the imbalance between the production and excretion of urate either from urate underexcretion, overproduction or both.

Gout can be extremely painful and although the cause of the pain severity is not fully understood, recent research suggests that the urate crystals provoke an inflammatory response from leucocytes and synovial cells, which trigger the release of cytokines that further intensify the local inflammatory reaction, and therefore pain (Busso and So, 2012).

Recommended treatment for gout includes NSAIDs, colchicine and corticosteroids, the latter administered either orally, intramuscularly or intra-articularly. Preventative treatments include allopurinol, which aims to lower uric acid levels, and are commenced once the patient’s acute gout attack has passed. The definitive diagnostic test for gout is via aspiration of the joint or tophus and the confirmed identification of MSU crystals (Burns and Wortmann, 2012). The presence of urate crystals confirms a diagnosis of gout, and the absence of evidence of infection will rule out septic arthritis.

As gout is an acute form of arthritis, the presenting symptoms can also appear similar to a range of other conditions and should be considered in the differential diagnosis. The key differential diagnosis in gout is septic arthritis and should be considered in any person who is systemically unwell (with or without a pyrexia) and has an acutely painful, hot, swollen joint, particularly when other joints apart from the MTP joint are affected, such as a knee or ankle joint.