Every week 12 young people die from undiagnosed cardiac conditions (Cardiac Risk in the Young (CRY), 2008). However, most of these conditions could be detected in life by simple compulsory screening. Until that day, there are usually two ways that ambulance staff could discover these undetected conditions: when the young person collapses or fits, or tragically, and sometimes inevitably, through cardiac arrest.

Sudden cardiac death (SCD) is usually arrhythmic, with underlying (subtle) structural heart disease, abnormal conduction, or ‘channelopathies’. If a healthy child or young adult develops cardiac-sounding symptoms or excessive breathlessness during or shortly after exercise, this may be structural heart defect. If a syncopal exercise is atypical, or if it occurs on exertion, this may be arrhythmic.

A 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG) is about 90% sensitive for these conditions, provided it is interpreted with the right expertise.

Subconsciously, we screen patients routinely on a daily basis, but we mainly concentrate on the elderly and historically tend to overlook the younger generation. The misconception is that they are too young to have any cardiac condition as these usually come with age, lifestyle abuse, or through long-term medication (changing this mindset is only a matter of education and more detailed investigations). Whatever you do for a 65-year-old’s chest pains you can do for a 15-year-old with the same.

Most cardiac conditions usually manifest themselves during exertion and exercise, so it goes without saying that if someone has an undiagnosed, inherited or acquired cardiac condition and they lead a reasonably sedentary life, they are less likely to show warning signs and symptoms as someone who is active in sport or exercise. Armed with this knowledge, previous episodes or red flag signs and symptoms become far more relevant, as does family history (such as epilepsy, family members dying, or cardiac conditions at a relatively young age).All this coupled with a 12-lead ECG could unearth a previously undiagnosed cardiac condition. If identified, the whole family could be referred for cardiac screening.

Classification of common heart conditions

Common heart conditions can be separated into two main categories: structural, which are detectable both in life and post-mortem, and chemical, which are detectable only in life. Examples of heart conditions within these categories are as follows:

Structural

Chemical

Common signs and symptoms

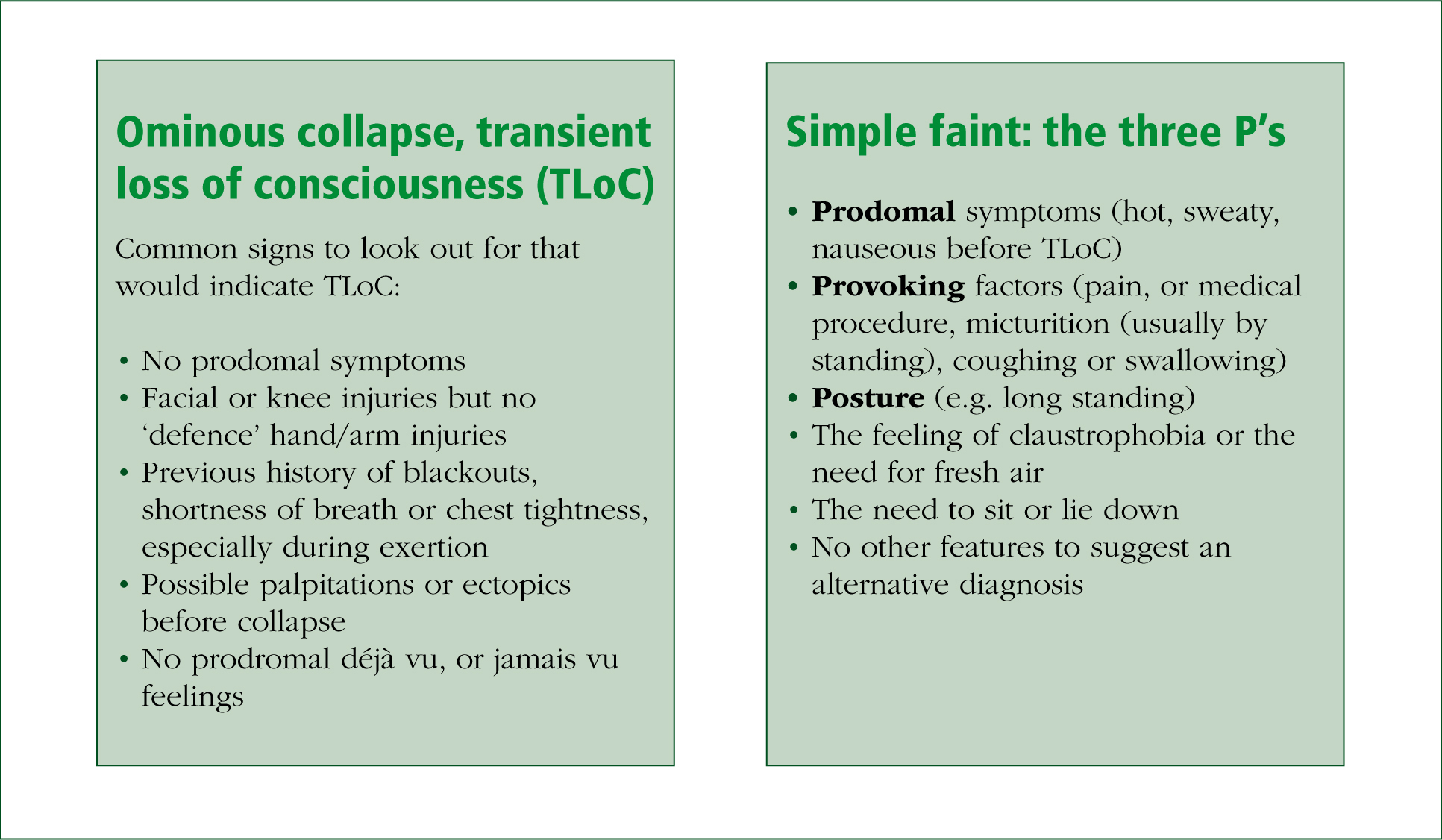

So how do you tell the difference between a simple faint and an ominous collapse, or an epileptic fit from a hypoxic fit? It is important to be able to tell the difference as this will form part of your patient history and may be the vital missing piece of the jigsaw, which could easily be overlooked (Figure 1).

Up to 30% of epilepsy is misdiagnosed (Jeffrey, 2000; Petkar et al. 2006), with a high number of cases that are actually possible cardiac hypoxic fitting. It is therefore possible that a sudden death in an ‘epileptic’ patient could actualy be the result of a possible cardiac event. Also, if epilepsy is misdiagnosed, then the individual could be confined to unnecessary lifelong medication with possible side-effects from these drugs, e.g. a driving ban and career and sport restrictions (Petkar et al. 2006).

Indications of an epileptic fit

The following signs are potential indications to suggest a person is having an epileptic fit (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2010a):

Another area that has been previously overlooked due to insufficient data at present is sudden unexplained drowning, mainly involving ion channels involved in long-QT syndrome (LQTS) and catecholamine polymorphic ventricular tachycardia (CPVT). Currently there is a need for more research in this area (Kenny and Martin, 2011), but LQTS and CPVT need to be considered in situations where a patient is attended who may appear to have suddenly drowned. This is because in many cases of sudden unexplained drowning the cause of death that is first established later proves to be incorrect.

Helpful resources available for the paramedic

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) have published a guideline for TLoC (2010a), with an accompanying ambulance slide set (2010b) to help health professionals implement the guideline. Among the advice offered, the slide set emphasises the importance of the following:

For further information, there are also two free educational training PowerPoint presentations, which are available for download. One is for medical and nursing staff, the other is for community education such as leisure centres, sporting organisations and schools.