On 15 August 2014, NHS England announced that ministerial approval had now been granted to commence preparatory work to take forward the proposal to introduce paramedic independent prescribing (PIP) to the public consultation phase, which commenced on 26 February 2015 and will cease on 22 May 2015. The consultation documents, entitled Proposals to introduce independent prescribing by paramedics across the United Kingdom (NHS England, 2015), invites comments on the proposed extension of prescribing, supply and administration of medicine responsibilities for UK-based paramedics, and is being undertaken alongside three other allied health professions (AHPs) medicines proposals, which include: independent prescribing by radiographers, supplementary prescribing by dietitians, and the use of exemptions by orthoptists. This article evaluates how prescribing rights for advanced paramedics (APs) has the potential to facilitate safe and efficient access to medicines, affording a robust rationale to support its introduction, and illustrates some of the potential benefits for service-users, the paramedic profession, healthcare providers/employers, and service commissioners.

Background

Paramedics traditionally operate in high-risk and often unpredictable environments, dealing with a range of illnesses and injuries from the critically ill, to those patients with low acuity, yet often challenging medical/psychological disorders. Historically, the training of ambulance personnel primarily prepared them for dealing with a cohort of life-threatening emergencies with specific emphasis on rapid transport to hospital. Such calls account for approximately 10% of all 999 calls made to the ambulance service. Consequently, 90% of patients have an urgent or social care need, many of which could be effectively managed at the scene by ambulance personnel (Darzi, 2008). Many such patients require either advice on self-medication/care, simple treatment in the community, ambulance transportation, make their own way to a healthcare facility, or necessitate a home visit to access ongoing care and medicines. Over the last decade, the number of calls received by the ambulance service has risen significantly from 4.9 million to over 9 million, 7 million of which resulted in emergency ambulance journeys (NHS England, 2013a). Of those transported to the emergency department (ED), over 40% were discharged home requiring minimal or no treatment at all (NHS England, 2013a). Published data suggests there are over 1 million avoidable admissions annually, and estimates nearly half of all 999 calls requiring an ambulance dispatch could be effectively managed by paramedics at the scene (NHS England, 2013a).

The NHS is expected to achieve £20 billion in cost-efficiency savings by the end of 2015 (NHS England, 2013b), through processes such as the Quality, Innovation, Productivity and Prevention (QIPP) Initiative, designed to drive forward quality improvements while achieving such savings (Department of Health (DH), 2011; NHS England, 2013b). Although significant progress has been made despite increased demand, mounting public expectations and costly technological/drug advances, efforts are still continuing, with the added pressure to achieve even greater savings in forthcoming years. Current planning assumptions by the DH (2013) have indicated a zero increase in funding for the next five years to 2020/21. External factors such as fiscal constraints and overriding political agendas create tensions within the NHS healthcare system, exacerbated by ageing populations with complex chronic conditions; immigration growth and infectious disease management (Health Protection Agency, 2011); and a reduction in junior doctors' working hours following revision of the Working Time Regulations Section 18(b) in 2003 (2003 No. 168). Such challenges have motivated the economic re-evaluation of conventional methods of service delivery, and have incentivised the introduction of pioneering new roles and broadened scope of practice for existing AHPs. Once a practitioner operating solely in pre-hospital care, the skills of paramedics are being increasingly recognised by other providers/employers, which has led to the creation of innovative new roles for paramedics throughout the healthcare sector.

The use of ambulance services for low-acuity clinical complaints, which could otherwise be dealt with by community care providers, such as GPs and pharmacists outside of the 999 system are increasing annually (NHS England, 2013a), which presents a significant challenge for many NHS ambulance Trusts. In many cases, paramedics are the first AHPs to assess the clinical and social needs of patients and play a crucial role in the provision of integrated care, managing acute illness/injury and chronic conditions in a range of settings. As such, APs possess the ability to dramatically reduce the number of preventable hospital admissions each year, significantly contributing towards the QIPP Initiative (Middleton, 2012). Undeniably, the paramedic role has witnessed dramatic changes over recent years from the traditional drivers of ambulances to expert clinicians delivering high-quality care. Historically, the training and scope of practice for UK paramedics varied widely nationwide, and was commonly facilitated in local training establishments with a distinct lack of outcome-focused research. Undergraduate paramedic training, in conjunction with experienced APs undertaking post-graduate courses, coupled with the introduction of tailored university-based courses, are collectively readdressing this balance, and producing greater quantities of published research, which informs evidence-based practice and enhances patient care delivery. Consequently, many paramedic education/training programmes have had to evolve to meet these needs and now provide education in a number of core competencies similar to that of medical students. Such changes were implemented to equip paramedics with the necessary knowledge and skills to undertake advanced practice roles in the future, and will make it easier for healthcare employers and commissioners of services to fully appreciate the potential utility of this cohort of clinicians.

The Department of Health Social Services and Public Safety (DHSSPS) defines three UK prescriber categories (DHSSPS, 2013:1):

The introduction of PIPs would require legislative changes, but presents an opportunity to challenge the traditional boundaries of paramedic practice, optimise service redesign opportunities, and support the evolutionary development of APs into senior clinical positions. PIP would engender a more flexible workforce, and facilitate a service that is more responsive to the needs of patients. Senior positions in many other acute and secondary care settings, such as the advanced clinical practitioner (ACP) are open to paramedic applicants, and are becoming increasingly popular with healthcare employers and commissioners nationwide. However, in the absence of prescribing rights, the paramedic profession is unfairly disadvantaged when compared to other AHP applicants, who by virtue of their role possess the legal rights to prescribe medicines. Accordingly, the introduction of PIP is pivotal if the positive predictive impact of such innovation is to be fully realised.

Current methods of drug administration by UK paramedics

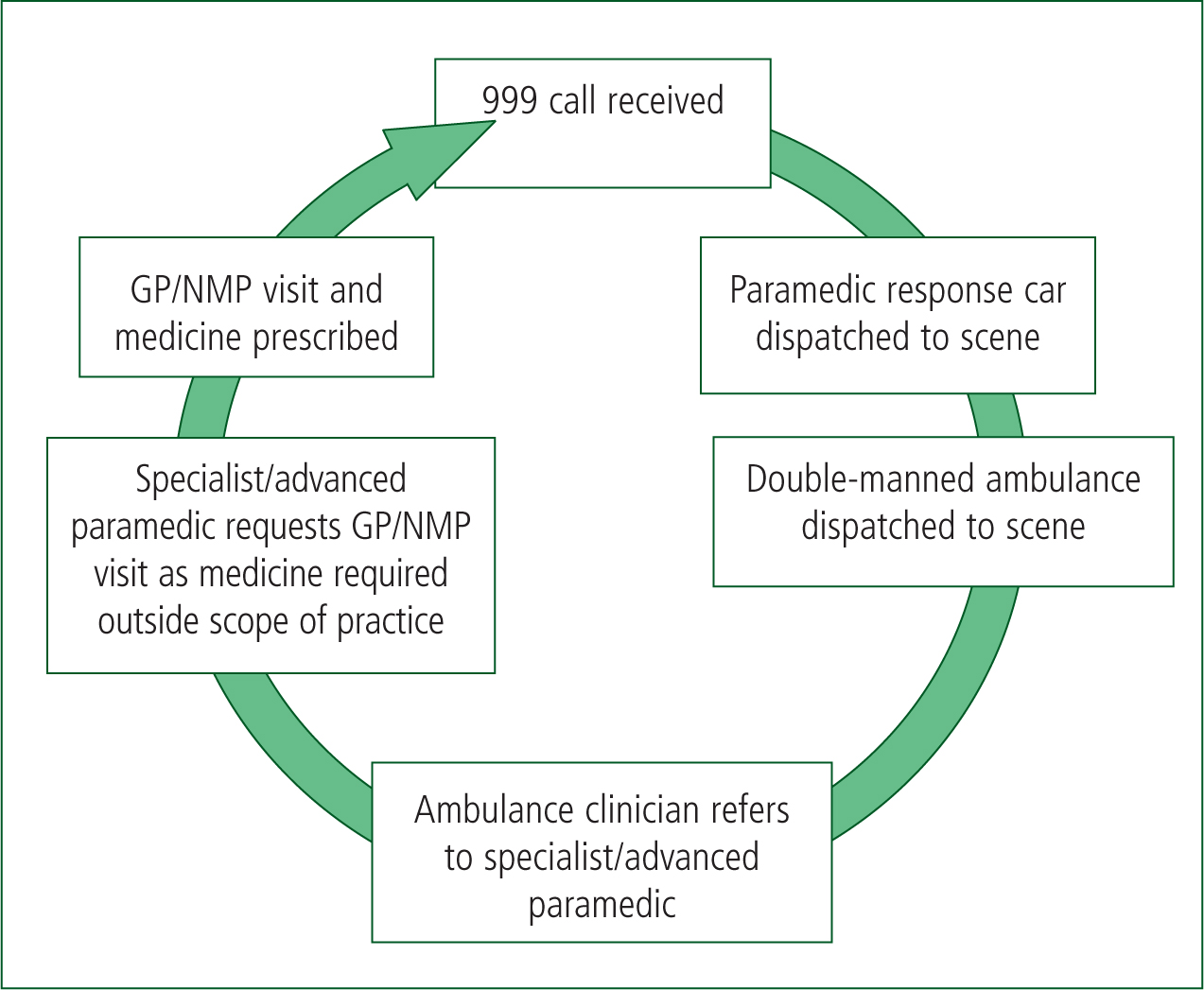

The Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (2013) have published a list of medications that registered paramedics can legally possess and administer on their own initiative for the treatment of patients in the absence of a prescription or under the advice of a prescriber. At present, UK-based paramedics administer a select number of medicines under nationally approved Joint Royal Colleges Ambulance Liaison Committee (JRCALC) guidance, complimented locally by patient group directions (PGDs), which vary significantly between ambulance Trusts. A PGD is a written instruction for the supply or administration of medicines to certain groups of patients, which has previously been authorised by a senior doctor/dentist and pharmacist. However, the creation of a PGD is often a lengthy and bureaucratic process, which are often too restrictive by design, and on many occasions present barriers for patients accessing specific medications due to their limited scope, often catering for only a small number of serious or life-threatening clinical scenarios. While PGDs do facilitate a means of administering specific medicines, they are simply not dynamic, nor responsive enough to be effective in many clinical settings given the diversity of medical conditions encountered. All AHPs/APs aspire to deliver optimal patient-centred care in a single care episode with greater autonomy, but are often hampered from doing so by current methods of medicine provision. In the context of local practice, paramedics routinely undertake history-taking and clinical examination proficiently to reach a preliminary diagnosis, and then consult with colleagues, other AHPs or medical/dental practitioners to obtain the required medication that is not available through a PGD. Consequently, the effective management of many conditions in the community requires multi-disciplinary input, often resulting in unnecessary conveyance to treatment centres, placing added strain on limited resources, and impacting adversely on acute and/or unscheduled care services in the UK (DH, 2010). An example of how recurrent inefficiencies can occur is detailed in Figure 1.

In total, five staff and three vehicles were involved during this single care episode. This is just one example of the recurrent inefficiencies witnessed daily in pre-hospital care nationwide. Attendance of a solo PIP may well have negated the involvement of other clinicians, thereby improving patient care/experience, optimising the use of limited resources, achieving cost-efficiency savings, while enhancing overall service resilience.

The future vision of healthcare provision

There are five distinct operating environments where the implementation of PIP has the potential to influence care provision. Each of the following arenas possess their own inherent benefits and unique challenges, and are detailed below:

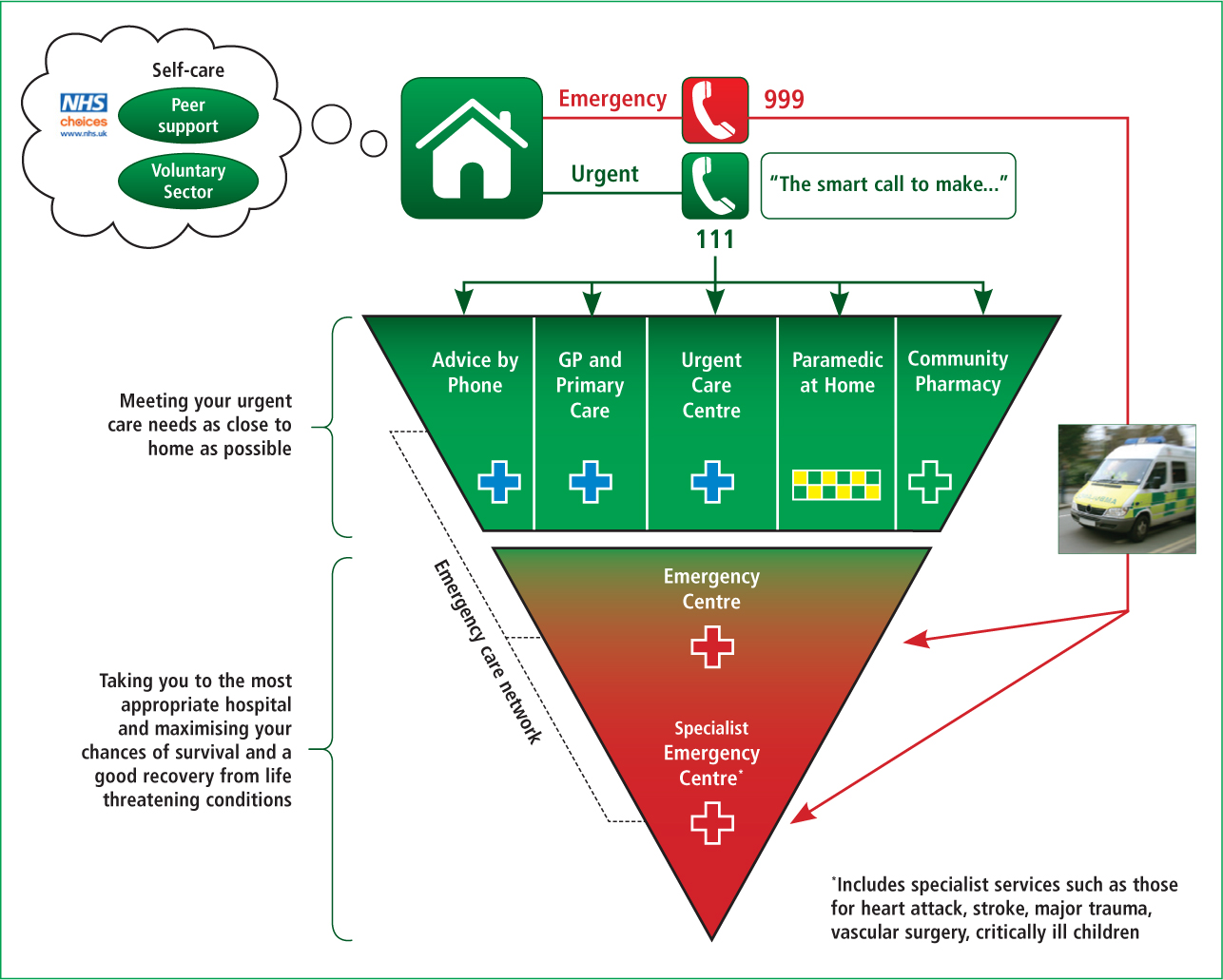

A visual representation of the future urgent and emergency care system (NHS England Urgent and Emergency Care Review Team, 2014: 8) can be seen in Figure 2. Given the growth in employment opportunities, APs/PIPs have the potential to contribute towards universal cost-efficiency savings in all key clinical arenas.

Although significant benefits are probable in the pre-hospital arena, the greatest predicted impact is in remote medicine, GP, PCCs, UCCs, or ED settings where a greater volume of patients are consulted. ED-based paramedic ACPs in possession of prescribing rights would be able to facilitate holistic care without the involvement of a third-party prescriber to complete a care episode, thereby enhancing patient/prescriber safety, and engender greater professional autonomy.

Non-medical prescribing (NMP) educational programmes: overview

Many professional groups have liaised with education providers and professional/regulatory bodies responsible for approving training courses to develop tailored programmes with standardised themes (Table 1) at either degree or post-graduate level. These courses necessitate attendance at university one day per week over a six-month period, plus 12 days of supervised clinical practice, with distance learning as an integral component.

| Clinical examination and diagnostic reasoning skills |

| Consultation and decision-making skills |

| Psychology of prescribing and factors influencing practice |

| Impact of prescribing, principles of patient monitoring and pharmacovigilance |

| Principles of clinical pharmacology and therapeutics |

| Professional standards and evidence-based practice |

| Managing risk and errors in prescribing |

| Legal, professional and ethical aspects of prescribing |

NMP courses: entry and supervision requirements

Course programmes and entry requirements differ between educational establishments. Although the core competencies remain largely generic, most undergraduate/degree schemes require evidence of literacy and numeracy skills at GCSE Grade C or above, combined with specific vocational qualifications. Many stipulate that applicants possess a minimum of 3 years' post-qualification experience, be registered with a regulatory body, and be legally permitted to prescribe medicines within their profession. Post-graduate applicants would typically possess a primary degree or equivalent qualification, and/or be able to demonstrate evidence of relevant professional experience. NMP courses require the student to produce a signed agreement from an appropriate doctor who has agreed to be the designated medical supervisor (DMS), who has experience pertinent to the student's field of clinical practice. Funding is commonly sourced centrally through clinical commissioning groups, employing NHS Trusts, Learning Beyond Registration (LBR) schemes or privately financed.

Critique of the literature assessing the capability of other NMPs

The demonstrable capabilities of other AHPs who now possess prescribing rights are well publicised, which mainly relate to nurses and pharmacist prescribers. Gielen et al (2014) appraised the impact of nurse versus physician prescribing, and critiqued over 35 publications. Of these, only 12 were UK based, and were predominantly undertaken within a primary care setting. The outcome measures included a comparison of the quantities and types of medications prescribed, patient satisfaction, and evaluated how these correlated with their physician colleagues. The study concluded that nurses prescribe in comparable ways to physicians, including the types, quantities, and dosages of medications (Gielen et al, 2014). Although nurses appeared to equal or exceed in terms of clinical parameters, perceived quality of care and patient satisfaction. The nurse prescriber's own perceptions included the delivery of patient-centred care, achieved time efficiencies and convenience for service-users, and delivered comparative levels of care (Gielen et al, 2014).

Daughtry and Hayter (2010) undertook a qualitative study of practice nurses' prescribing experiences and found improved efficiency, primarily associated with timely, high-quality care, with speedy access to appropriate medicines. These and other well conducted UK-based studies by Smalley (2006), Stenner et al (2009; 2011) and Tinelli et al (2013) all found widespread acceptance of NMP, which not only demonstrated consistently high levels of patient satisfaction, but also safe and effective medicines provision. In addition, a significant number of small studies evaluating NMP in primary care settings emphasised other potential benefits, such as enhanced professional/patient relationships, and a greater understanding of the patient's medical history, which enhanced overall patient experience. Arguably, such benefits primarily lend themselves more towards primary/urgent care settings where patients are consulted on more than one occasion, rather than pre-hospital care or EDs where clinicians commonly undertake a single short period of consultation and/or treatment.

In contrast to many of the published benefits, some studies implied that pharmacists undertake insufficient patient contact and lack the diagnostic skills necessary to prescribe safely (Tonna et al, 2007: 555; Cooper et al, 2008). The paramedic profession retains an advantage in this area of practice, as paramedics must be able to demonstrate competency in clinical examination, diagnostic reasoning and decision-making as part of basic and regular update training. Concerns that some AHPs, including future PIPs, may prescribe outside their level of competence are apparent. However, these should not present a barrier to the introduction of PIP, but instead invoke the implementation of proactive monitoring with regular review/revision, comprehensive support/training, and robust clinical governance mechanisms, capable of identifying, and if necessary, reprimanding offenders across all professions. That said, such palpable success over two decades of NMP should be duly considered, and the wealth of knowledge and experience should be used to inform commissioners of healthcare services to develop implementation strategies for PIP nationwide.

Many of the issues affecting other AHP groups who are either seeking, or who have recently acquired prescribing rights, are indeed common to the paramedic profession; some of which are detailed in Table 2.

| Overwhelming willingness of APs to become PIPs |

| Established ability to safely deliver medications in a diverse range of settings |

| High predicted benefits for patients through improved access to consultations and medications |

| Extension of NMP rights to other AHPs, including paramedics, is featured in the NHS modernisation agenda |

| Political drivers to support the expansion of NMP rights to paramedics |

| Increasing public support and acceptance of NMP |

| Resistance from medical colleagues to expand prescribing rights to AHP groups due to a perceived lack of confidence—mainly attributable to the lack of training standardisation comparable to that of a medical degree |

| Work semi-autonomously/autonomously—concerns over the ‘loose cannon’ in unsupervised practice situations. |

Undeniably, accurate diagnosis, prompt access to medicines and lifelong lifestyle changes play a fundamental role in the prevention and management of illness and disease (NHS England, 2013b). Although legislative changes have slowed the momentum for the introduction of PIP, the fact remains that NHS ambulance services continue to provide unprecedented levels of high-quality unscheduled care to many acutely and chronically-ill patients every day, actively diagnosing and safely treating a diverse range of clinical conditions.

However, there is significant scope for APs with enhanced clinical examination skills, diagnostic interpretation skills, and PIP to make an enhanced contribution to the care their patients receive in a climate of heightened demographic and economic change. Paramedics play a pivotal role in the emergency and urgent care system, often acting as a conduit for other NHS services, and considering the multiplicity of specialist roles available to it, the paramedic profession has the potential to play a hugely significant role in the future redesign of modern healthcare systems. However, these roles must be introduced strategically and under strict governance if maximum impact of such roles is to be achieved.

Some ambulance Trusts have begun to deliver short ‘in-house’ or ‘top-up’ courses for their existing paramedics, and then applying titles such as advanced or specialist paramedic, in lieu of completing nationally recognised university-accredited courses. Many would argue that a large number of these courses simply enrich existing skills, and provide little in terms of enhanced scope of practice, which introduces confusion for service-users, potential employers and service commissioners. The apparent lack of formal governance currently in place, which details what knowledge and skills constitute the award of each title is concerning. The College of Paramedics provides clear guidance on curricula competency and scope of practice for paramedics, and as part of the development of the proposal to introduce independent prescribing by paramedics, a paramedic profession specific draft Practice Guidance has been produced (College of Paramedics, 2015). This will inform the requirements for paramedics in practice, along with the Outline Curriculum Framework for AHPs who prescribe.

Many AHPs, including paramedics, undertaking advanced clinical roles are Master's-level educated practitioners with wide-ranging clinical experience, and yet are severely limited in the care they can offer their patients in the absence of prescribing rights. PIP would underscore the evolution in autonomy for paramedics, and facilitate a means of providing holistic, seamless, less fragmented episodes of care for patients in a much broader range of clinical settings. PIP would add a tier of experienced APs capable of delivering both a reactive and proactive approach to health care provision. Autonomous practice would also create employment opportunities, improve role satisfaction, provide personal and professional development, and enhance the reputation of the paramedic profession. However, if the anticipated benefits of PIP are to be fully realised (Table 3), radical ambulance service redesign, including the re-commissioning of many traditional services to achieve long-term universal benefits, is essential.

| Patient | Clinician |

|---|---|

| Prompt access to medicines and consultation | Optimise patient care through improved access to medications |

| Single clinician involvement per care episode | Greater professional autonomy |

| Experience patient-centred care | Delivery of patient-centred care |

| Reduced morbidity/mortality through timely access to medicines | Improved employability into advanced practice roles—greater role diversity |

| Improved care in the community—fewer avoidable hospital admissions | Greater role visibility and improved acceptability (public and professional) |

| Greater patient safety through early management of illness and disease | Improved inter-professional collaboration |

| Fewer ambulance journeys to hospital | Reduced patient/clinician risks, compared with third party prescribing |

| Reduced need for multi-disciplinary involvement | Greater professional accountability and role satisfaction |

Conclusions

In summary, the author's recommendation is that HCPC-registered APs who have successfully completed higher education at Master's level, who are practising at an advanced level, and who have successfully completed an approved NMP programme with an integral period of supervised practice under the guidance of a medical practitioner, be afforded independent prescribing rights. Such innovation is paramount if APs are to actively contribute towards tackling the burden of unprecedented demand, limited resources and the relentless necessity to achieve cost-efficiency savings within the modern NHS.

Implications for future practice

The NHS is one the UK's most valued institutions, but predictive trends of increased demand and the necessity to achieve cost-efficiency savings threaten its sustainability (NHS England, 2014). Consequently, to remain safe and fit for the future, the NHS must proactively evolve and challenge the traditional boundaries of professional practice, re-evaluate existing service delivery strategies, and innovate future care provision models (NHS England, 2014). Table 4 summarises the potential impact of PIP on future practice.

| Delivery of high quality, patient-centred care by an autonomous practitioner = cost-efficiency savings and enhanced role satisfaction |

| Improved NHS efficiencies: 1. A single clinician response per care episode 2. Reduction in avoidable ambulance journeys = staff/fuel/servicing/wear/time efficiencies 3. Improved resilience 4. Reduced burden of avoidable admissions |

| Reduced morbidity/mortality through early access to medicines |

| Enhanced credibility among peers, stakeholders and service-users—improving public perception and professional reputation |

| PIP may well achieve cost-efficiency savings when compared to the provision of additional out-of-hours/locum GP cover |

| Improved employability within both the pre-hospital and in-hospital settings |

| Protracted on-scene times, replication of services and tensions between AHP groups |

| Service-user education promoting appropriate use of healthcare services remains a significant challenges for service design managers |

Milestones and future hurdles

The timeline detailed in Table 5 is purely indicative, and the proposal process may end at any time. Should each stage be successful, it is anticipated the remaining steps of the process should be complete within a 12-month period.

| Milestones and future hurdles | Date |

|---|---|

| DH/NHS England and MHRA agreed case for need | Completed May 2014 |

| DH/NHS England NMP Boards to review/approve professional applications detailing cases of need | Completed July 2014 |

| Ministerial approval for the commencement of preparatory work to take PIP forward to public consultation | Completed August 2014 |

| The College of Paramedics, Association of Ambulance Chief Executives and Health Education England recruit a project officer to work with NHS England AHP Medicines Project Team | Completed November 2014 |

| Public consultation process commenced: 26 February–22 May 2015 | Ends 22 May 2015 |

| Analysis of data and public opinion—presentation of a consultation report | Mid/late 2015 |

| Submission of consultation findings to the Commission for Human Medicines who will give final endorsement for PIP and will then formulate ministerial recommendations | Decision expected by autumn/winter 2015 |

| Ministerial processes to implement changes to legislation and statute permitting PIP | Dependent on the decision of CHM |

| The first APs may well be able to access NMP courses to become future PIPs | Late 2016 |