Cases of severe or complex entrapment pose significant challenges for prehospital clinicians for several reasons. First, the nature of complex entrapments may mean access to provide lifesaving interventions is limited. Second, extrication techniques may create further hazards to both rescuers and patients, such as destabilisation of surrounding structures. These cases are often associated with road traffic crashes (RTC), but may also result from incidents involving industrial machinery and following structural collapses.

Entrapment can be categorised as physical, in which a patient cannot be removed without intervention to create space, or medical, in which factors such as suspected injuries prevent immediate extrication (Fenwick and Nutbeam, 2018). The rate of physical patient entrapment following an RTC is low. A study of all RTCs in the West Midlands requiring fire and rescue service (FRS) attendance for extrication between October 2010 and March 2012 found the rate of physical entrapment to be 12% (36/296) (Fenwick and Nutbeam, 2018). Nonetheless, the length of the prehospital phase of care has been demonstrated to be a significant factor in mortality following trauma (Brown et al, 2016) and entrapment has been observed to be a contributory factor in extending this time period (Dias et al, 2011; Nutbeam et al, 2014).

Prehospital amputation

In cases in which extrication is not possible within a reasonable time frame to prevent the death of the patient, or because of clinical deterioration or a scene safety emergency, limb or extremity amputation is indicated (Porter, 2010). This procedure may also be performed when the limbs of deceased patients are preventing access to live victims, or to facilitate the removal of a non-survivable limb with minimal attachment that is preventing extrication of the patient (Porter, 2010). These four indications occur extremely rarely and, as such, there is limited available evidence to support decision making.

Incidence

A survey distributed to 200 United States emergency medical service directors by Kampen et al (1995) identified a rate of 0.29 cases per year, and only two out of 143 respondents reported that their agencies had a written policy regarding prehospital amputation. Similarly, Sharp et al (2009) published the experiences of a ‘field amputation team’ established in 1984, which had performed a total of nine prehospital amputations at the time of publication—a rate of 0.36 cases per year. Most recently, a review of requests for trauma surgeons to attend the scene of an incident in the Miami-Dade County area from 2005–2014 reported that prehospital amputation was performed on three patients (Pust et al, 2016).

It is difficult to determine prevalence in settings without established arrangements for a prehospital surgical response, such as following natural disasters. The procedure is reported to have been performed on multiple occasions following several earthquakes around the world (Mustafa, 2010; Ardagh, 2012) but specific details are not provided. There are also several reports of amputation being performed on deceased victims (a procedure called dismemberment) to gain access to live patients (International Search and Rescue Advisory Group, 2011), which requires equally complex decision making.

For rarely performed or novel treatments, analysis of the information in case reports or case series may be an important research contribution (Naik and Abuabara, 2018), especially when experimental investigation is unethical (Nissen and Wynn, 2014).

Scoping reviews may be used to analyse the literature available and identify the main concepts and knowledge gaps in particular subjects (Tricco et al, 2018). The study used this approach to analyse reports of prehospital amputation to gain an understanding of the factors involved and highlight areas for further investigation in this rare, complex procedure.

Methods

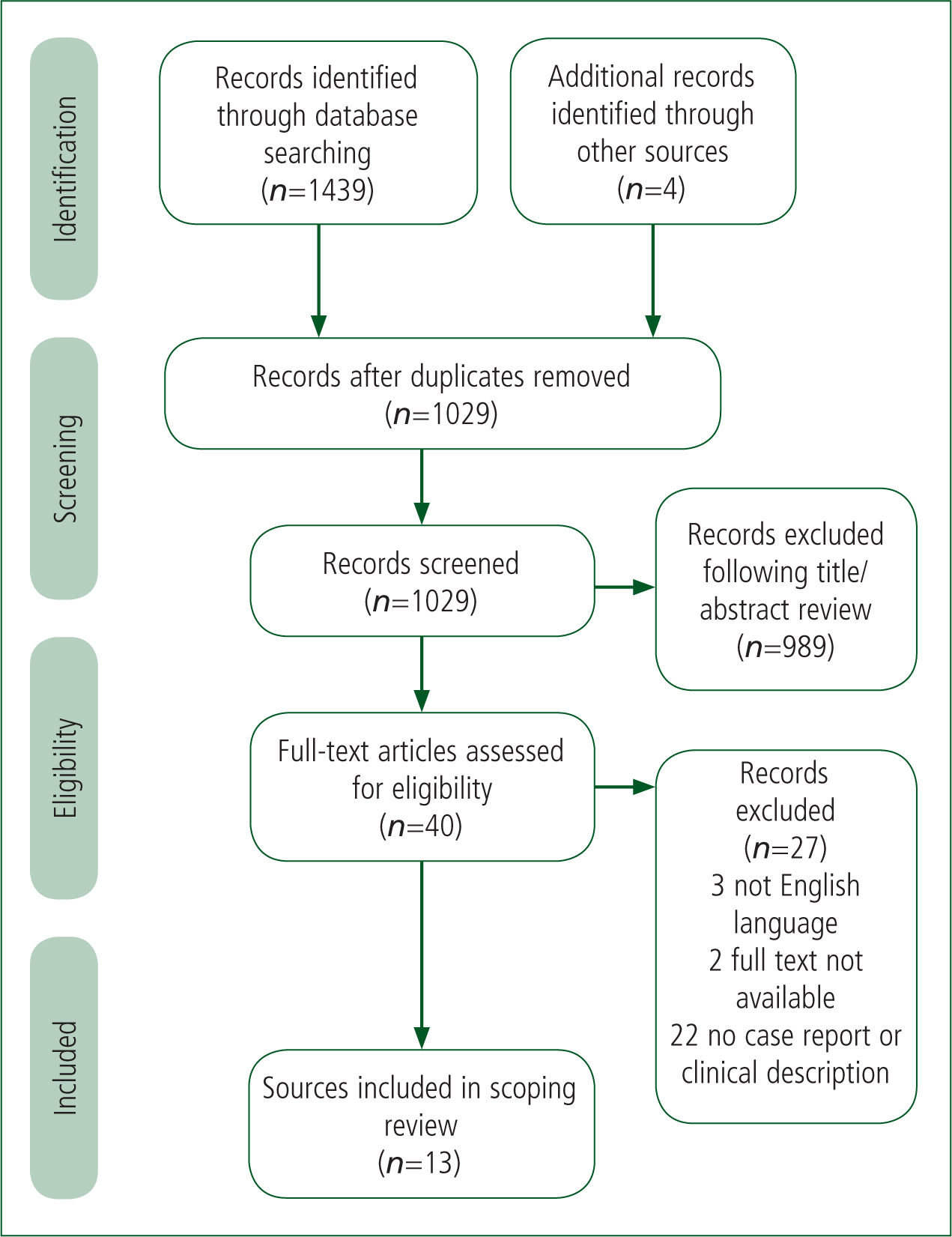

This scoping review is structured in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidance on scoping reviews (Tricco et al, 2018) (Figure 1). To identify reports of prehospital amputation, a systematic search of multiple databases (Allied and Complementary Medicine Database (AMED), British Nursing Index (BNI), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Emcare, Google Scholar and PubMed) was undertaken using a Boolean search strategy. A title and abstract search of the terms shown in Table 1 was performed using the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Healthcare Databases Advanced Search website and Google Scholar. Additionally, grey literature and reference lists of search results were reviewed to identify additional articles. No date parameters were specified so any changes in practice over time could be identified. Articles were selected for inclusion if they featured a case report, case series or clinical description of prehospital amputation. Reports from websites and the media were not included for analysis to reduce the risk of reporting bias and maintain clinical accuracy. Articles were not included if the full text was not available, not in the English language or did not clearly refer to amputation procedures being performed in the prehospital setting.

| ‘amputation*’ OR ‘dismemberment*’ OR ‘limb removal’ OR ‘disarticulation’ |

| AND |

| ‘prehospital’ OR ‘pre-hospital’ OR ‘scene’ OR ‘field’ |

The eligible literature was analysed to obtain data on the incident type, procedure performed, reason for the procedure, equipment used, medications administered and patient outcome. Two reviewers independently reviewed the literature and recorded the data. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion between the two reviewers or further evaluation from a third reviewer. These data variables were chosen as areas of interest to identify factors that may be considered in practice or for further research.

Results

The search strategy produced 1439 results. A further four articles were identified through a review of grey literature. Duplicates were removed, then the titles and abstracts of 1029 records were reviewed for relevance to the subject. During this phase, 989 records were removed, leaving 40 articles to be assessed for eligibility. Three were removed as they were not published in the English language, and the full text was not available for two articles. In addition, 22 records were removed as they did not contain a case report or a description of a case of prehospital amputation. A final total of 13 articles describing 20 cases of prehospital amputation or dismemberment were included.

Incident type

Prehospital amputation or dismemberment was performed following structural collapse in a total of eight cases, which was the most frequently reported scenario in which the procedure was required. Industrial accidents were responsible for six cases, with RTCs described in five cases and rail incidents in one.

Anatomical area

Seventeen cases involved the complete amputation of an extremity and two cases involved the amputation of a distal region—one of the forefoot and one of the digits. One case of dismemberment reported partial removal of a lower limb.

Entrapment by a lower limb was the most common mechanism of entrapment, reported in 15 patients. The surgical completion of a limb that was already partially amputated because of the precipitating event was required in six cases. Amputations requiring bone dissection or disarticulation were performed in 13 patients.

Decision making

Regarding the decision to perform amputation, in six cases, rapid extrication was required because the patient had a time-critical condition. Seven cases reported amputation being performed to facilitate extrication following unsuccessful attempts to release the patient from entrapment or entanglement using traditional methods. Five patients required amputation so they could be removed from a hazardous environment in which prolonged extrication attempts were deemed too dangerous. Two separate cases of dismemberment were performed to identify a deceased victim and to gain access to live patients.

Amputation because of clinical deterioration and the need for rapid extrication was performed most often as a result of an RTC. In comparison, situations in which standard extrication methods were attempted but not possible without amputation occurred most often as a result of industrial accidents.

Equipment

The equipment used to perform the procedure was not reported in 14 cases. Traditional amputation tools such as a Gigli saw, amputation knife and scalpel were used in five cases. The use of a non-traditional tool—a reciprocating saw—was reported once.

Medications

Analgesic and sedative medications administered during the procedure were documented in 15 of the 20 reports of amputation. Of these, morphine was administered as a sole medication four times, and in combination with midazolam and fentanyl on one separate occasion each. Ketamine was administered to five patients, twice as the only medication, twice with midazolam and once with propofol. The use of fentanyl was documented three times, within the same case series, and was used alongside midazolam in all. There was one reported use of a combination of diazepam and inhaled nitrous oxide. Two reports were made of rapid sequence intubation being performed before the procedure; however, the medications used to facilitate this were not stated.

Patient outcome

Patient outcome was documented in 17 cases. Two reports were of dismemberment of already deceased patients, and patient outcome was not described in one case. All 17 patients survived to hospital but one was reported to have died in hospital 3 days after extrication.

Discussion

This scoping review identified 13 sources of evidence reporting prehospital amputation or dismemberment in a total of 20 patients, which were published between 1975 and 2018. Observations from the literature identified provide a good insight into the types of situation in which this procedure may be required and may also indicate several areas for further research, such as optimal methods and tools for amputation.

While procedural methods vary, there appears to be an established consensus on the indications for performing this procedure and the decision-making process is generally well described. The literature search process also highlighted that, although prehospital amputation is rarely performed and documented, a number of media reports and anecdotal accounts have been made of this procedure in recent years, which may hold further valuable information.

| Author | Incident type | Procedure | Reason for procedure | Amputation equipment used | Analgesic/sedative medications administered | Patient outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Finch and Nancekievill (1975) | Rail incident | Above-ankle amputation | Extrication not possible without amputation | Not stated | Ketamine | Unknown |

| Stewart et al (1979) | Structural collapse | Completion of partially amputated right leg performed via knee disarticulation | Prolonged extrication deemed too dangerous because of risk from destabilising structure | Not stated | Morphine | Survived |

| Dunn et al (1989) | Industrial accident | Bilateral disarticulations at the elbow joints of both arms | Extrication not possible without amputation | Not stated | Diazepam, inhaled nitrous oxide | Survived |

| Foil et al (1992) | Industrial accident | Transection of the humerus | Extrication not possible without amputation | Gigli saw | Morphine | Survived |

| Structural collapse | Amputation of the fourth and fifth digits of the left hand | Prolonged extrication deemed too dangerous because of risk from destabilising structure | Not stated | Not stated | Survived | |

| Jaslow et al (1998) | Structural collapse | Completion of a partially amputated right leg | Prolonged extrication deemed too dangerous because of risk from destabilising structure | Scalpel | Morphine | Survived |

| Ebraheim and Elgafy (2000) | Road traffic crash | Bilateral below-knee amputations | Extrication not possible without amputation | Not stated | Rapid-sequence induction (medications not stated) | Survived |

| Ho et al (2003) | Road traffic crash | Above-knee amputation of left leg | Rapid extrication required because of time-critical patient condition | Reciprocating saw, shears, scalpel | Ketamine | Survived |

| Sharp et al (2009) | Industrial accident | Dissection of the soft tissues of the lower right leg | Extrication not possible without amputation | Not stated | Midazolam, fentanyl | Survived |

| Industrial accident | Dissection of soft tissues to complete partial amputation of right leg | Extrication not possible without amputation | Amputation knife | Midazolam, fentanyl | Survived | |

| Industrial accident | Transmetatarsal forefoot amputation | Extrication not possible without amputation | Scalpel, Gigli saw, 3.0 silk ties, haemostats | Morphine, midazolam, fentanyl | Survived | |

| Macintyre et al (2012) | Structural collapse | Amputation of right arm | Prolonged extrication deemed too dangerous because of risk from destabilising structure | Not stated | Ketamine, Midazolam | Survived |

| Structural collapse | Above-knee amputation of the left leg and mid tibia-fibula amputation of right leg | Rapid extrication required because of time-critical patient condition | Not stated | Rapid-sequence induction (medications not stated) | Deceased (3 days after extrication) | |

| Structural collapse | Dismemberment of the lower extremity | Dismemberment of deceased victim required to gain access to live victim | Not stated | Not required | N/A | |

| Structural collapse | Dismemberment of right arm and right hind quarter | Dismemberment required to ensure victim identification | Not stated | Not required | N/A | |

| Petinaux et al (2014) | Structural collapse | Amputation of right arm | Prolonged extrication deemed too dangerous because of risk from destabilising structure | Scalpel, Gigli saw | Ketamine, midazolam | Survived |

| Pust et al (2016) | Road traffic crash | Amputation of right arm | Rapid extrication required because of time-critical patient condition | Not stated | Morphine, midazolam | Survived |

| Road traffic crash | Completion of partial amputation of the left leg and knee disarticulation of the right leg | Rapid extrication required because of time-critical patient condition | Not stated | Morphine | Survived | |

| Emerson and Coogle (2018) | Road traffic crash | Through-knee amputation of the right leg | Rapid extrication required because of time-critical patient condition | Not stated | Ketamine, propofol | Survived |

| Bunyasaranand et al (2018) | Industrial accident | Completion of a partially amputated right femur | Rapid extrication required because of time-critical patient condition | Not stated | Not stated | Survived |

The settings in which prehospital amputation has been described are varied. Entrapment within industrial machinery is frequently documented within the literature. Incidents of this nature pose particular hazards and challenges to rescue teams in relation to both their own safety and patient management. Entrapment may occur in areas of limited access, in which standard extrication equipment cannot be operated or may create a risk of further injury to the patient or rescuers (Foil et al, 1992). The position of the entrapped patient may also present challenges for airway management, haemorrhage control and patient assessment.

The main challenges of working within this environment are perhaps best summarised in an account of bilateral forearm amputation to free a patient from a mechanical grinder by Dunn et al (1989). The authors noted the difficulty in performing a detailed assessment because the entrapped limbs were severely entangled in the machinery and estimating blood loss was hindered by pooling within surrounding materials. Additionally, this case report and several others highlighted crowd control as being an additional complicating factor to rescue efforts in terms of preventing the maintenance of a sterile field around the patient and placing others in danger.

Structural collapse is the commonest situation in which the procedure is reported to have been undertaken, accounting for eight out of 20 described cases. Other circumstances include natural disasters, such as earthquakes, and events such as explosions because of gas leaks or bombings. Victims can sustain multiple injuries and are often trapped under dense rubble and debris for prolonged periods of time, which necessitates expedient medical care and extrication upon discovery (Statheropoulos et al, 2015). However, provision of medical care may be hampered because of the effects of the precipitating event, such as secondary collapse, loss of infrastructure or unavailability of rescue resources (Bartels and Van Rooyen, 2012).

The literature describing cases of structural collapse frequently refers to the risk of using extrication methods that could destabilise structures being a crucial factor in determining the need for amputation to be performed. A case series involving this scenario also provided examples of the need for dismemberment of deceased victims and the additional medico-legal considerations to be made in these cases (Macintyre et al, 2012). The complexities of providing clinical care within collapsed structures are well described and reinforce the need for specialist resource attendance, such as urban search and rescue and hazardous area response teams, at such incidents.

RTCs are also a frequent cause of documented prehospital amputations and are often reported because rapid extrication is needed to treat an immediately life-threatening situation. Similarly to industrial accidents, entrapment or entanglement within badly damaged vehicles may restrict the ability to carry out treatment throughout extrication attempts. The inability to provide adequate clinical care to entrapped patients, such as control of haemorrhage or airway management, is clearly a time-critical emergency. Reassuringly, despite seemingly poor prognosis at the time of initial assessment by medical teams on scene, the cases in which this is described all report patient survival following amputation and extrication.

A paucity of information is available on the equipment used to perform amputations, with the majority of articles not providing this. However, a number of cases involved the dissection of soft tissues only, so it may be assumed that equipment such as a scalpel would have been sufficient to achieve this. When selecting the tool, a number of considerations should be made. Traditionally, a Gigli saw is used to cut through bone and its use is reported on three occasions. However, the use of this tool requires optimal patient positioning and adequate space so it may not be suitable in all settings. One case report refers to the use of a reciprocating saw to perform part of the amputation because space was restricted around the patient. The use of non-traditional tools such as these to perform an amputation provides a thought-provoking scenario for clinicians. FRS extrication equipment, such as powered cutters, have been suggested as a viable alternative to conventional medical devices in life-threatening situations in which only firefighters are able to safely access the patient (Leech and Porter, 2015). Their use, in addition to other novel techniques, is an interesting area of further research.

Administration of analgesia or sedation is frequently described and the range of medications reported in the literature supports the need for a tailored approach based on patient requirements and situational factors. The variety of medications used may be influenced by other factors, such as clinician familiarity and scope of practice, or their availability in the prehospital environment at a particular location or date. Rapid sequence induction is reported twice, with several authors reporting that the procedure was considered but avoided because of a number of factors, including clinical instability or a lack of space for monitoring or airway management. Ketamine was administered in a number of cases and may be a suitable agent because of its favourable haemodynamic profile and analgesic, amnesic and sedative effects (Sheth et al, 2018). No adverse complications as a result of medication administration are noted in the literature.

Details on patient outcome are given in the majority of reports; however, follow-up periods and the level of detail provided vary. No reports describe death from complications solely as a result of prehospital amputation. One patient unfortunately died 3 days after extrication; however, they had been entrapped for more than 48 hours before they were discovered and were reported to be in a critical condition when found.

Clearly, as amputation is often performed as a last resort in critically injured patients, a high level of clinical care is required throughout the extrication phase. Because of the complexity of such cases, this will often mean tbat patient care is provided by a number of agencies. It is therefore important that all emergency services, which are likely to respond to such cases, are aware of the clinical and logistical requirements.

Limitations

This scoping review has several limitations. It is based on a small number of case reports, case series and descriptions of prehospital amputation undertaken in a variety of settings, so findings may not be generalisable to all prehospital systems.

During the search process, a number of media reports documenting incidents involving prehospital amputation became apparent but these were not included with the reviewed studies. Case reports are also at risk of positive-outcome publication bias (Nissen and Wynn, 2014) and, therefore, the literature included within this review may contain a higher proportion of cases with successful outcomes than what is seen in practice.

This scoping review excluded literature that was not published in the English language for ease of analysis. However, this may mean that additional reports of prehospital amputation performed in other international prehospital systems, several of which are physician-led, were not included. This limits the opportunity to make comparisons between areas including decision making, equipment used and medications administered. Although the search strategy was applied to several databases and the reference lists of search results were manually screened for additional literature, it is possible that further eligible sources of evidence may not have been included.

Conclusion

This scoping review has identified a number of reports describing prehospital amputation performed in a variety of circumstances. Although case reports and case series may not provide sufficient detail to draw conclusions on prevalence and epidemiology, several key learning points are consistently identified by their authors and should be emphasised to those likely to respond to such incidents.

Most importantly, because of the frequently complex and hazardous nature of such incidents, informed decision making and shared situational awareness between all agencies involved is paramount. The patients in which this procedure is undertaken are often severely injured and will require the capabilities of advanced trauma teams. This reinforces the need for early mobilisation of such resources to incidents that may result in the need for prehospital amputation.

This review also highlights the requirement for focus on several other areas, including the delivery of clinical care in hazardous environments and multi-agency training in extrication from unusual entrapments.

Clinicians should be aware of the indications for this procedure; however, because of its diverse nature, the development of a well-evidenced universal protocol is difficult. A further review incorporating consensus statements, procedural guidance on prehospital amputation and studies evaluating the use of non-traditional tools may be beneficial.