Respiratory failure following a chemical, biological, radiation or nuclear (CBRN)incident is primarily due to the direct affectsof the agents used (Baker, 1996), but it may also be due to hypoxia from associated non-cardiogenicpulmonary oedema, or airway obstruction secondaryto reduced conscious levels (Muskat, 2008). CBRNinduced respiratory failure is amenable to prompttreatment resulting in successful resuscitation ofcritically ill patients (Okumura et al, 1996; Stacey etal, 2004) but delays in treatment can be devastating(Schiermeier, 2002). Although treatment mayfacilitate successful resuscitation the performanceof emergency skills are complicated by the need ofthe responding rescue personnel to wear bulky andcumbersome CBRN-Personal Protective Equipment(CBRN-PPE) which is known to adversely affectfne motor skills (Castle et al, 2009). However, failure to wear CBRN-PPE can result in health careprofessionals becoming casualties (Nozaki et al,1995; Nakajima et al, 1997; Geller et al, 2000; Stacey et al, 2004).

A cuffed endotracheal tube (ETT) is consideredto be the gold standard airway for casualties withrespiratory failure associated with reduced levels ofconsciousness with delays in intubation resultingin increased morbidity (Liisananntti et al, 2003).However, wearing CBRN-PPE has a negative impacton intubation performance (Flaishon et al, 2004;Castle et al, 2009) which may in turn increase patientmortality/morbidity by worsening hypoxia. To date, only Talbot and colleagues (2003) have lookedat intubation aids while wearing CBRN-PPE bycomparing standard intubation with intubation viathe Intubating Laryngeal Mask (ILMA). MacDonald et al (2006) allowed the use of stylets but this wasnot as part of a randomized controlled evaluation, whereas Garner et al (2004) provided both styletsand gum elastic bougies during their CBRN-PPEstudy, but did not record whether clinicians utilizedthese devices.

Therefore, 25 clinicians (Table 1) all of whomhad been recruited into a previous researchstudy looking at performing intubation and otheremergency skills while wearing CBRN-PPE (Castle etal, 2009; 2010a) were interviewed to ascertain their opinions as to what types of intubation aids mayimprove intubation performance. The purpose of thisstudy was to identify intubation aids that warrantedfurther evaluation for use in a CBRN environmentand a qualitative research methodology was chosento minimize the impact of the authors perceptionson choice of intubation aids.

Total interviewed: 25 from a population of 75 potential participants from Castle et al (2009)

Methods

This was a qualitative, interviewed-based studydesigned to gauge the opinions and views of agroup of UK based non-homogenous cliniciansregarding what intubation aids should be evaluatedfor use while wearing CBRN-PPE. Twenty-fveclinicians (Table 1) were recruited. All participantshad previously been recruited to a manikin-basedresearch study looking at the feasibility/diffcultiesof performing intubation, insertion of a laryngealmask, intravenous cannulation and insertion of anintraosseous needle while wearing the currentlyissued National Health Service (NHS) CBRN-PPE.

Participants were asked questions as part of a semi-structured interview and individual responseswere then further explored. All responses weretaped, transcribed and then coded with themesbeing identifed (Chiovitti and Piran, 2003). Tominimize the risk of interviewer generated bias arefective journal was maintained and followingeach interview the researcher reviewed the tapes tomonitor for leading questions (Chiovitti and Piran,2003). Tapes were erased as per research protocol.

A minimum of two clinicians (Table 1) fromeach of the professional subgroups recruited intotwo studies previously conducted by Castle et al(2009; 2010a) were recruited. Interviews continueduntil the minimum numbers of interviewees wererecruited and no new devices were identifed, thereby achieving theoretical saturation (Chiovitti and Piran, 2003). To minimize the risk of recruitmentbias all participants who come forward duringthe recruitment phase were interviewed untilminimum numbers across all professional groupswas achieved. This resulted in over recruitment insome subgroups (Table 1). All interviewees gave written informed consent and this study receivedethical approval from the Surrey Research EthnicsCommittee (no 08/H1109/224).

Results

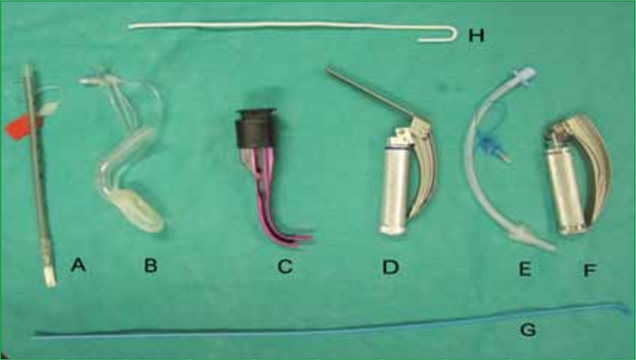

Five intubation aids (Table 2) were identifed withvarying frequency during the interviews (Figure 1). In addition to intubation aids participants alsoidentifed the importance of correct/optimal patientpositioning, practising intubation while wearingCBRN-PPE and the availability of a skilled assistant.With the exception of patient positioning andpractise all techniques were identifed with bothpositive and negative comments. Two intervieweesalso identifed surgical airway.

The gum elastic bougie was the most populardevice (23/25) described as

‘…essential equipment’ MP (consultantanaesthetist) ‘…I use one for all my intubations’ J (EMtrainee) ‘…I don’t intubate without a bougie beingavailable’

However, six interviewees highlighted that the lossof dexterity due to wearing CBRN-PPE gloves wouldaffect the use of a bougie

‘…picking it up with the butyl gloves would bediffcult’ participant D (anaesthetic trainee) ‘…it will be diffcult with the thick gloves’participant (J resuscitation offcer (RO)) ‘…I don’t think it would help it’s too fddly’.

Interviewee PK (consultant anaesthetist) identifedthat the design of the bougie was not ideal for usewhile wearing CBRN-PPE

‘…it needs to be thicker’.

In addition, two interviewees identifed that thegloves would remove the sensation obtained whenintubating with a bougie

‘…you wouldn’t feel the clicks as bougie passesover the tracheal ridges’ interviewee N (EMconsultant).

Interviewee N also noted that an assistant wouldbe required for optimal use of a bougie but alsohighlighted that the assistant would also be requiredto wear CBRN-PPE. Interviewee M (paramedic)identifed that a bougie would not assist withintubation if the intubator’s vision was obscured bythe visor (Figure 2).

Both the stylet and the Airtraq™ were identifed by15 interviewees. The main rationale for the stylet wasthan it would minimize the fne motor skill requiredto intubate

‘…would make intubation a gross skill’interviewee S (pre-hospital care doctor) ‘…the stylet will give you a bit more rigidity’

Two interviewees highlighted the ability of thestylet to pre-shape the ET-tube

‘…if you can get it angulated you can gostraight in to the trachea’ interviewee G (EM trainee) ‘…its less wiggle than a bougie and you canpreshape the tube’ interviewee D (traineeanaesthetist).

A number of issues were identifed with regardsto the use of a stylet to include the risk of localizedtrauma

‘…you can damage the trachea’ interviewee Y(trainee anaesthetist) ‘…they are more traumatic’

Three consultant anaesthetists stated a personaldislike of stylets

‘…a ridge introducer should never be used’interviewee K (anaesthetist) ‘…may help to get the tube where youwant it to go because you are more clumsywearing CBRN-PPE’ interviewee P (consultantanaesthetist).

The negative comments regarding the stylet maypotentially refect UK anaesthetic practise

‘…stylets aren’t very popular in the UK’interviewee H (RO).

Two interviewees identifed potential diffcultiesin placing the stylet into the ET-tube while wearingCBRN-PPE due to loss of fne motor skills anddiffculty in opening packaging

‘…as long as the stylet was already in the tube’interviewee S (EM consultant) ‘…but need to be pre-packed in the ET-tube’.

Interviewees identifed the Airtraq™ stating thatthey believed that the improved vision of the larynxwould improve intubation success

‘…you get direct vision of the cords’ interviewee S (consultant anaesthetist)

Interviewee B (anaesthetic trainee) stated it

‘…maybe fddly but it will give you a perfectview’ ‘…because you are not having to co-ordinate alaryngoscope in a suit’.

Three interviewees stated that they had found theAirtraq™ particularly easy to use while intubating innormal clothing

‘…have found it a lot easier to use than alaryngoscope’ interviewee M (paramedic) ‘…I didn’t fnd them easy without a suit so Idon’t think it would help’.

Interviewee Y (anaesthetic trainee) highlightedthat

‘…people aren’t familiar with the Airtraq™and you need to practise with it every day’.

The ILMA was highlighted by ten intervieweesas a potential intubation aid with interviewee M(paramedic) stating

‘…it’s pretty fit for purpose’.

Two interviewees referred to its potential as anintermediate airway and this was supported byinterviewee Y (anaesthetic trainee)

‘…would be useful because if you can’tintubate you can still use it to ventilate’.

A number of potential issues with regards tointubating via the ILMA were identifed

‘…putting in the ILMA is easy but getting thetube through the cords can be diffcult…it canget stuck’.

Interviewees S (consultant anaesthetist) said thatremoving the ET-tube was fddly

‘…Its tricky getting the tube out of the ILMA…probable leave the LMA in and remove it later’.

The concept of leaving the LMA in situ onceintubation had been successful achieved was furthersupported by interviewee B (anaesthetic trainee)

‘…and you can leave in the LMA as you don’thave to fddly taking it out’.

In general the ILMA was believed to be awkwardto insert and this was confrmed by interviewee D(anaesthetic trainee)

‘…ILMA may help but it would be fiddly’.

In addition, clinicians may not be experiencedwith its use

‘…not a lot of experience with using it’ interviewee M (consultant anaesthetist).

As with the stylet a degree of personal preferencewas also expressed

‘…I don’t like them very much’ interviewee PK(consultant anaesthetist).

The McCoy laryngoscope was identifed by fveinterviewees with interviewee Y (anaesthetic trainee)stating

‘…McCoy, stylet and bougie are all methods fordiffcult intubation’ ‘…McCoy laryngoscope would make intubationeasier’ ‘McCoy might be helpful…but they don’tconvert a diffcult situation to a perfect onethey sometimes just improve the situation’.

The only negative comment was from intervieweeC (EM consultant) who noted that using the McCoylaryngoscope would imply

‘…multiple laryngoscopes would need to beavailable’.

Of the non-intubating aids practise and trainingwere identifed by eight interviewees. Interviewee B(paramedic) stated

‘…training is essential…practise is the key…you need to get the suit on and practise’.

Interviewee J (EM trainee) stated that a

‘structured training programme would reduceanxiety’ ‘…people get used to intubating the manikin’.

Interviewee J was supported by interviewee B(paramedic)

‘…people need to invest the time puttingthe suits on…half a day every four to sixmonths…you’re also got to moulage unless youdone that then training is a tick box exercise’.

Patient positioning was identifed as a keyelement in achieving successful intubation by sixinterviewees. Interviewee B (paramedic) states

‘…moving them off the foor should bestanding operating procedure’ ‘…if I had the luxury I would chose to use atrolley’.

Interviewee B (paramedic) added

‘I would immediately go for an LMA and thenoptimise the position of the patient before goingto intubation’.

Discussion

The issue of optimal pre-hospital airwaymanagement is subject to continued discussion andmuch of traditional paramedic airway managementtechniques pre-dates the development of thenumerous supra-glottic airway devices that arenow available. A number of supra-glottic airwayswere identifed in the 2010 European ResuscitationCouncil Guidelines (Deakin et al, 2010) asalternatives to intubation during the management ofcardiac arrest. Castle et al (2011b) recently publishedresults of a manikin-based randomized control trialcomparing a number of different supra-glottic airwaydevices following a similar interview-based study(Castle, 2010c).

Currently within UK pre-hospital care supra-glottic airway devices and intubation aids are usedwith variable frequency by both paramedics andother pre-hospital clinicians. The aim of this studywas to identify which intubation devices cliniciansbelieved may improve intubation performance whilewearing CBRN-PPE and therefore warranted furtherevaluation in a randomized controlled study. All theclinicians interviewed in this study had previouslyattempted intubation (of a manikin) while wearingCBRN-PPE (Castle 2009; 2010a).

A number of key factors were identifed duringthese interviews beyond the use of intubation aidsalone. A key belief being that prior to intubation, patients should be positioned in the optimal positionand that intubation on the foor while wearingCBRN-PPE should be avoided. All intervieweeshad previously taken part in a study by Castle et al(2010) that demonstrated intubation on the foor wasmore diffcult to perform when wearing CBRN-PPE.Subsequently, Castle et al (2011a) also evaluated intubation on the foor compared with intubationon an ambulance trolley, further demonstratingthe importance of patient position on intubationperformance.

The importance of training in emergency skillswhile wearing CBRN-PPE was also highlighted asclinicians tended to improve skill performance byrepeating skills while wearing CBRN-PPE (Geller et al, 2001; Castle et al, 2009; 2010b), and thisimprovement in skill performance occurred acrossall disciplines to include experienced intubators.Krueger (2001) highlighted the importance of‘realistic’ CBRN-PPE training due to the negativeimpact of CBRN-PPE on skill performance. Theoptimal frequency of training while wearing CBRN-PPE is yet to be determined, though evidence fromresuscitation training demonstrates that clinicalskills (e.g. basic life support) deteriorate withintwelve months (Castle et al, 2007; Soar et al, 2010)with skill deterioration being noticeable after threemonths (Soar et al, 2010). Interviewee B (paramedic)recommended a training frequency of between fourto six months which has been shown to improveresuscitation based skills (Soar et al, 2010).

With regards to intubation aids, the gum elasticbougie was identifed by nearly all of the participantsrefecting its role within UK intubation practice(Henderson et al, 2004). It is generally believedthat bougie assisted intubation improves both thespeed and success of diffcult intubation (Gataure et al, 1996; Noguchi et al, 2003; Messa and Kupes,2011; Marugama et al, 2011), however, Woollard et al (2009) noted that the bougie, when used byparamedics, was slower to use and had a lowerintubation success rate when compared with a stylet.

A number of interviewees identifed issueswith picking up the bougie and one intervieweehighlighted the requirement for an assistant. Animportant consideration identifed by a number ofinterviewees is that the butyl gloves would removethe ‘feel’ of the bougie passing over the trachealrings which is used as an indicator that the bougiehas entered the trachea (Henderson et al, 2004).The deterioration in tactile sensation and loss of fnemotor movement due to wearing CBRN-PPE is asignifcant factor in skill performance. Krueger (2001)noted that hand steadiness reduced by 30 %, two-handed fne dexterity by upwards of 55 % and single-handed dexterity by 30 % due to the thickness of thebutyl gloves (Krueger, 2001). In addition, the CBRN-PPE’s visor can affect clarity/depth of vision (Figure2) as found in Castle (2010a). Despite these issues, the bougie remains integral to the UK’s diffcultairway protocol and is considered to be superior tothe stylet. (Gataure et al, 1996; Noguchi et al, 2003)

The stylet was less popular than the bougiepotentially refecting the clinical background of the interviewees who were all practicing clinicians in theUK although some of the interviewees had receivedtheir training outside the UK. Two paramedics weretrained in South Africa where the use of a stylet isstandard practice and one anaesthetist was trainedin Australia and another trained in the Ukraine. TheUkrainian anaesthetist had primarily been trainedin the use of the stylet (within the Ukraine) butfollowing exposure to the bougie, within the UK, now states a preference for its use.

Two interviewees stated that for optimalperformance the stylet should be pre-positionedwithin the ETT as opening sterile packaging requiresthe retention of fne motor skills which is reducedby the CBRN-PPE butyl gloves (Coates, 2000). Theresearch by Krueger (2001) is equally pertinent tothe stylet as it is the bougie. The principle beneftof the stylet as identifed by the interviewees is thatthe stylet can be used to pre-form an ETT into anoptimal intubating shape (Noguchi et al, 2003; Walls et al, 2008). Interviewees also highlighted that thestylet would make the ETT more ridged and less‘clumsy’, although the risk of localized trauma washighlighted (Walls et al, 2008; Austin, 2010).

The ILMA and the McCoy laryngoscopes areboth established diffcult intubation aids (AmericanSociety Anesthesiology; 2003Henderson, 2004;Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthesia,2011), and typically these devices are used onlyfor the management of diffcult airways which mayreduce the frequency that an intubator gets to usethese devices. Until recently, both the ILMA and theMcCoy laryngoscope were only available as multipleuse devices and were therefore relatively expensive.Both devices are now available as single-use itemsmaking them cheaper which may result in theirgreater availability.

A number of interviewees believed that the ILMAwould be as easy to insert as a LMA because LMAinsertion is easier to perform while wearing CBRN-PPE than traditional intubation (Flaishon et al, 2004;Castle et al, 2009; 2010a). However, a number ofinterviewees stated that the ILMA would be ‘a fiddle’to use as a blind intubation device with two issuesbeing identifed; diffculty in blindly passing theETT into the trachea and the process of removingthe LMA over the ETT once intubation had beenperformed. Two of the interviewees stated that theywould leave the ILMA in situ and remove it in moreideal conditions and this appears to be a potentialcompromise.

The success rate for blind intubation via anILMA is variable with Menkenzies and Manji (2007)reporting a 100 % successful insertion rate in aparamedic manikin study but Choyce et al (2000)reported a success rate of only 67 % on the frstattempt, rising to 95 % by the third, findings alsosupported by Wahlen et al (2009).

Interviewees identifed that using an ILMA wouldfacilitate prompt ventilation prior to successfulintubation by allowing a number of breaths to begiven via the ILMA. Menkenzies and Manji (2007)highlighted this function of the ILMA in a ‘simulated’diffcult airway model and reported time to frstbreath (as an LMA) of 34 seconds (24–116 range) andthe blind placement of an endotracheal tube withina mean of 75 seconds (53–254 range). In all of thesecases, traditional intubation had failed. Currentlythe ILMA is the only device within the context ofCBRN-PPE that has been evaluated against standardintubation within a randomized controlled trial.

The main issue identifed with regards to theMcCoy laryngoscope was the potential need toprovide numerous laryngoscopes. This could be circumvented by just using the McCoylaryngoscope for all intubation attempts as theMcCoy laryngoscope can be used like a traditionalMacintosh blade if the intubator prefers, simply bynot engaging the ‘leveller’ that lifts the tip of thelaryngoscope blade. However, the loss of fnger/thumb dexterity caused by wearing CBRN-PPE maywell have a negative affect on the intubator’s abilityto activate the lever which lifts the epiglottis.

The Airtraq™ was identifed by 15 interviewees asa potential device for use while wearing CBRN-PPE, primarily because it provides an excellent view ofthe larynx. Woollard et al (2008) demonstrated thatin a diffcult intubation model, qualifed and studentparamedics performed better with the Airtraq™than with a standard Macintosh laryngoscope.This ease of use and improved intubation successachieved with the Airtraq™ has also been confrmedin the obese patient (Ndoko et al, 2008), patientsat increased risk of diffcult intubation (Maharaj etal, 2008), as well as demonstrating an improvedsafety profle when intubating patients with cervicalfractures (Hirabayashi et al, 2008). In a non-CBRNstudy of a diffcult intubation Maharaj et al (2007)noted that the Airtraq™ was more popular withnovice intubators and faster to use than the McCoylaryngoscope or the ILMA. However, Maharaj et al(2007) reported that both the McCoy and the ILMAwere faster and easier to use when compared totraditional intubation resulting in a higher intubationsuccess.

Despite gaining excellent views of the larynxwith the Airtraq™, intubation is not ensured if theintubator does not modify their intubation techniquewhen using the Airtraq™ (Dhonneur et al, 2009).This issue was identifed during the interviews andhighlights the importance of practise with the devicebefore utilizing it for intubation following a CBRNincident.

Surgical airway was identifed by two participants, both serving military anaesthetists. This refectscurrent UK military practice to use surgical airwayover traditional intubation by ‘infrequent intubatorswithout access to intubation drugs’, however, outsidemilitary confict, airway management surgical airwayis more traditionally seen as a failed intubation skill(American Society Anesthesiology, 2003Henderson;2004; Australian and New Zealand College ofAnaesthesia, 2011).

Internationally diffcult airway guidelines differslightly with the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists (2010), referring to all ofthe devices highlighted during these interviews. TheUK (Henderson, 2004) and the American guidelines(American Society Anesthesiology, 2003) refer to allof the devices with the acceptation of the Airtraq™(or other similar devices), although this is likely to refect when the guidelines were published and nota reflection on the Airtraq™, as the Airtraq™ andother optical intubation aids are gaining popularity.

Future research

The intended purpose of this qualitative studyand the similar study published by Castle (2010c)is to identify further areas of research (Table 3).A qualitative approach was chosen to minimizeresearch-based bias in the selection of the devices tobe reviewed.

Conclusion

This interview-based study has identifed a numberof established intubation aids that clinicians believemay assist with the speed and success of intubationwhile wearing CBRN-PPE. Following analysis ofthis data it is intended to complete a manikin-basedrandomized control trial comparing the impact ofa gum elastic bougie, Airtraq™, stylet, IntubatingLaryngeal Mask airway and the McCoy laryngoscopeon the speed and success of intubation whilewearing NHS CBRN-PPE.

It is of interest to note that training whilewearing CBRN-PPE and patient positioning wasalso identifed as important variable in improvingintubation success rates while wearing CBRN-PPE, despite all the interviewees being qualifedintubators. Despite identifying a number ofintubation aids that may improve intubationperformance, the interviewees also highlighted thenegative impact of loss of fne motor movement andtactile sensation due to the integral butyl rubbergloves as a possible limitation of the identifeddevices. Therefore, intubation aids warrant furtherevaluation within the CBRN context as dose the roleof training in skill performance while wearing CBRN-PPE.