Paramedics find themselves called to digit dislocations, which is challenging as they can present in various ways. Digit dislocations bring residual damage to tissue and underlying structures from prolonged displacement owing to misaligned bones. The paramedic's objective is always to get the dislocation reduced as soon as a possible, which was eluded to by Simpson et al. (2012) who identified that quick and safe out-of-hospital reduction was a far better option than transport to an accident and emergency (A&E) department.

It can be advantageous to reduce discomfort and pain for the patient more quickly, thus reducing anxiety and emotional stress, and at the same time limiting further tissue damage. The specialist or advanced practitioner needs a good understanding of the anatomy and techniques required to undertake a detailed evaluation and assessment of the injury, and identify any complications that could unfold (Freiberg et al. 2006). With various specialist and advanced practitioners now working across a variety of clinical environments bringing additional knowledge and skill, they are able to recognise and treat a number minor injuries, which includes in-depth assessment of digits and soft-tissue damage. Specialist or advanced practitioners undertake accurate and informed clinical decisions, underpinned by specialist knowledge and education, and taking into account the patient's wishes and concerns. This allows for a patient-centred approach and appropriate patient consultation. Specialist or advanced practitioners must be transparent about the available choices, reducing poorly informed decisions, and making way for their patients (who must clearly demonstrate capacity) to make good choices. This article will look at the evidence for out-of-hospital digit reduction, namely the proximal interphalangeal joint (PIPJ) in a dorsal presentation. After reviewing the evidence, the author will determine if the procedure is safe and effective in this new and emerging arena.

Search strategy

Bibliographic database search

| AMED | Allied and Complementary Medicine 1985 to present Allied health professions, complementary medicine |

| CINAHL | Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature. 1981 to present Nursing, allied health professions |

| MEDLINE | General medical database. |

These databases were selected to search as medical, nursing and allied health professions were all considered. A number of searches were run using key words, and inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied as discussed in more detail in the following section.

Keyword search

A search was run with the following key words:

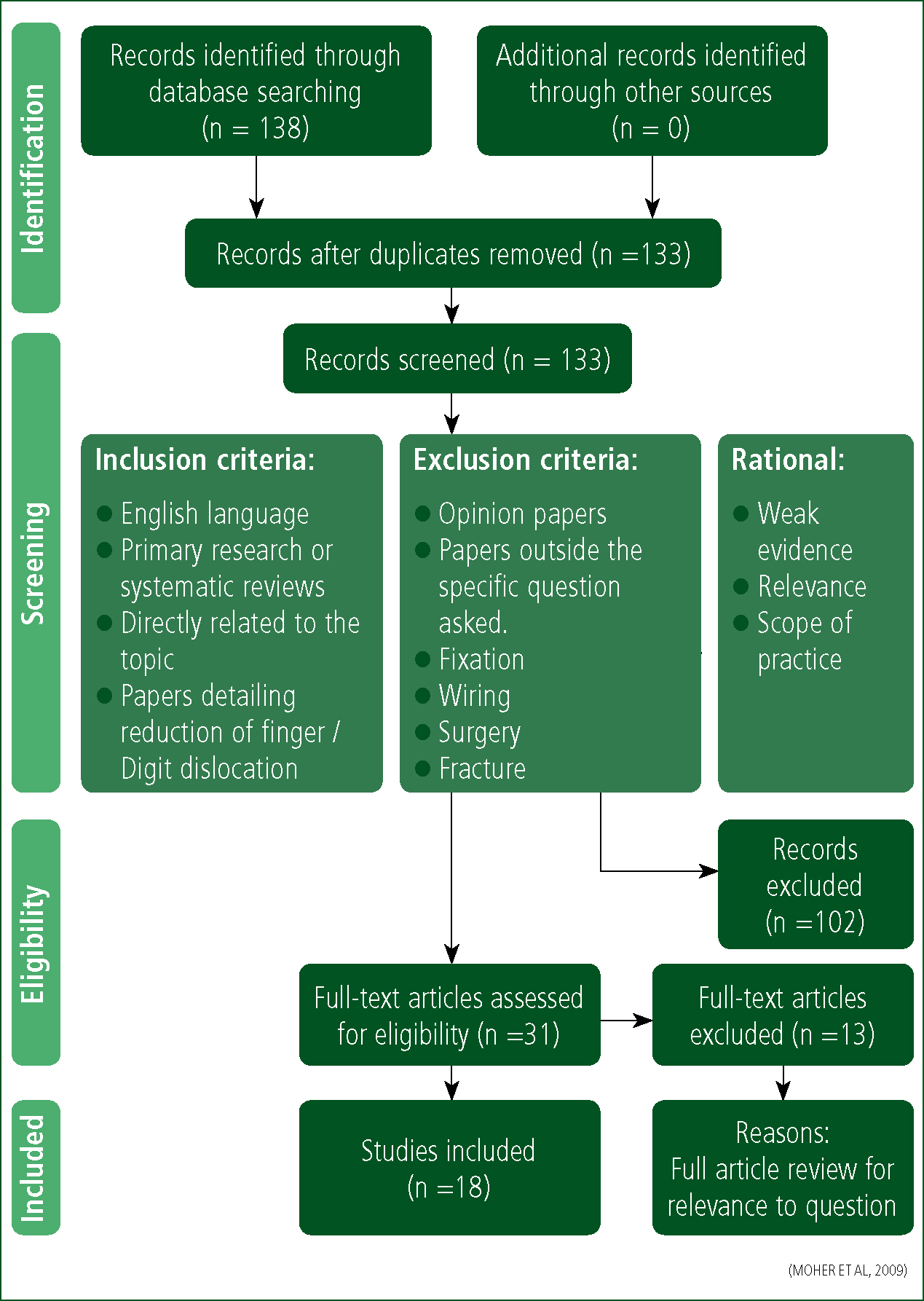

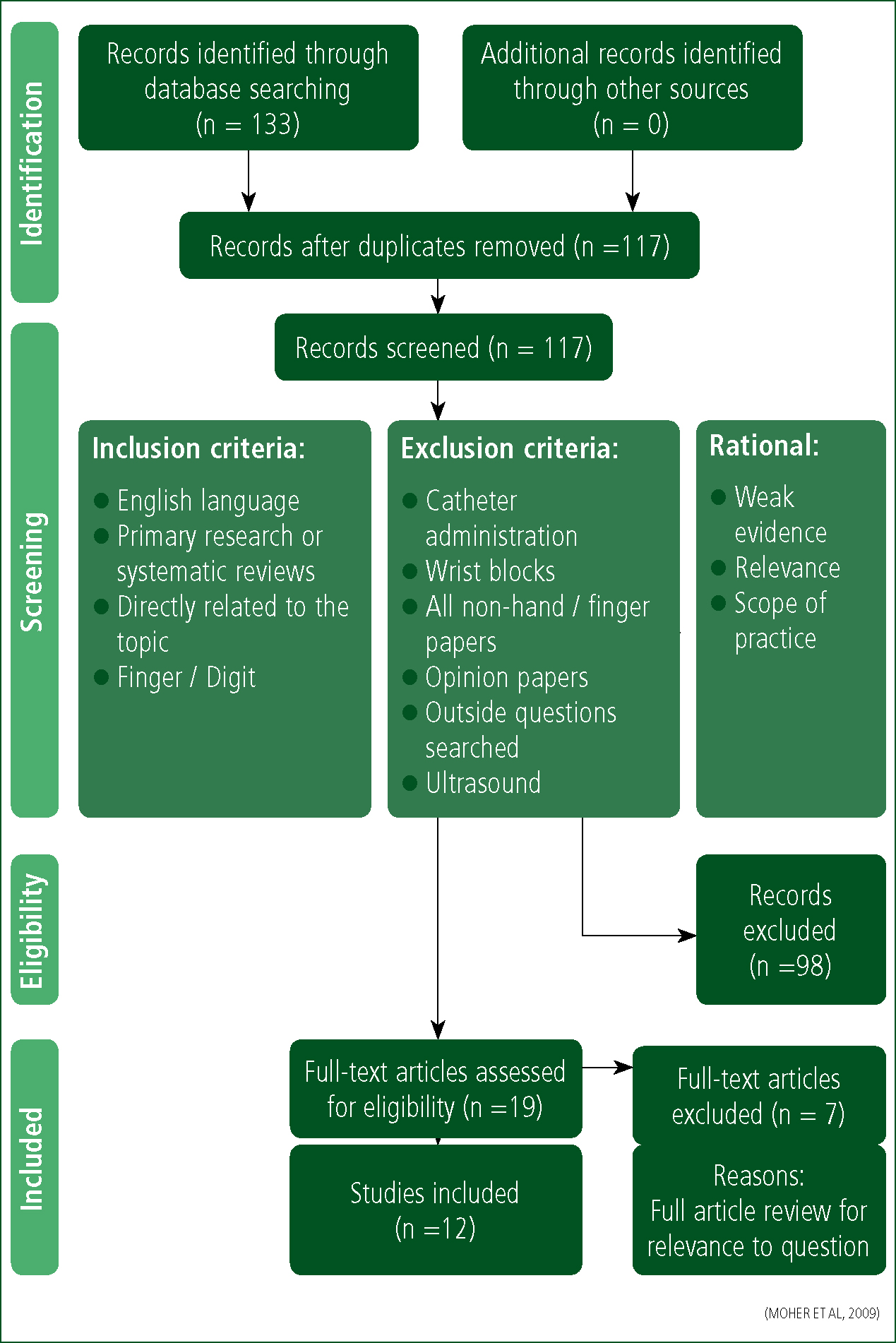

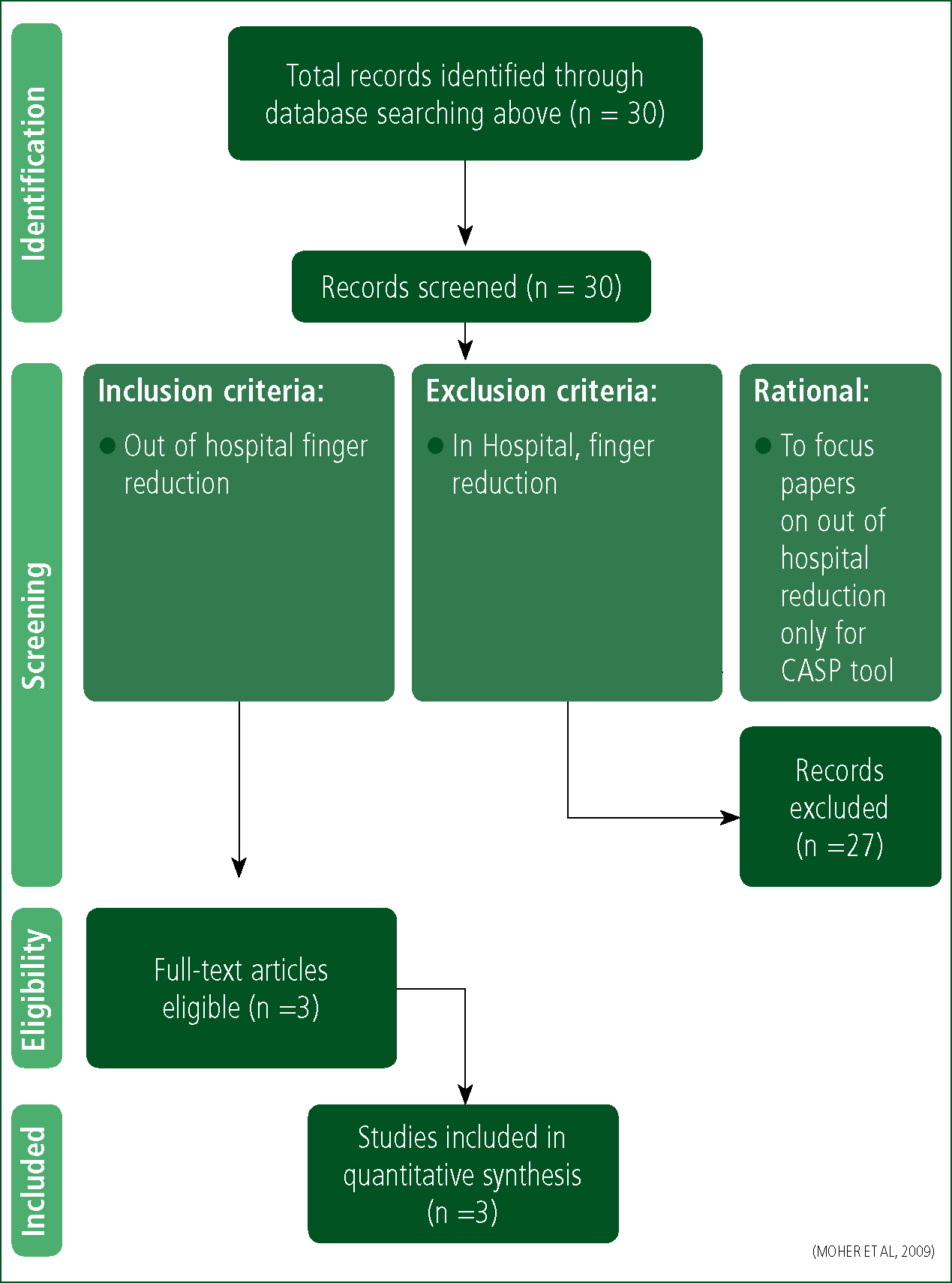

This search yielded 138 results (Table 1), which, after the removal of duplicates, produced 133 papers (Figure 1). Inclusion and exclusion criteria in Table 2 were applied. The second search (Table 3) then yielded 132 searches which, after duplicates, was filtered to produce 117 papers (Figure 2). Inclusion and exclusion criteria in Table 4 were then applied. This left a total of 30 results to be considered. The author then reviewed the combined 30 papers for out-of-hospital application only, which reduced the final results to three papers (Figure 3).

| Search Terms | Databases searched | Final results |

|---|---|---|

| (‘finger* reduc*’) OR (finger dislocate*) |

AMED / CINAHL / MEDLINE | N = 21 |

| (Finger dislocation) |

CINAHL / AMED / MEDLINE | N = 39 |

| (Dislocations AND Fingers) OR Finger Injuries) AND keyword ‘reduction’ |

MEDLINE / AMED / CINAHL | N =5 |

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| English language | Surgery / Fixation |

| Primary research or systematic reviews | Fracture / wiring |

| Directly related to the topic | Operation |

| Search Terms | Databases searched | Final results |

|---|---|---|

| (MH ‘Neuromuscular Blocking Agents’) OR (MH ‘Nerve Block’) |

CINAHL | N = 13 |

| (MH ‘Neuromuscular Blocking Agents’) OR (MH ‘Nerve Block’) |

MEDLINE | N = 120 |

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| English language | Catheter administration |

| Primary research or systematic reviews | Wrist blocks |

| Directly related to the topic | Opinion papers |

| Outside questions searched for ultrasound |

Clinical decision-making

Kovacs and Croskerry (1999) point out that clinicians use a variety and range of clinical decision-making approaches. These are dependent largely on the unique characteristics of individual clinical situations, and the environments in which paramedics find themselves. The role of the clinician is a complex one; it centres on performing a range of assessments to gather, evaluate and synthesise information relating to a patient's presentation, before deciding on appropriate treatment and transport (Sanders 2005; Caroline et al. 2009). Throughout this process, clinicians must continuously evaluate and judge the degree to which they are making the correct clinical decisions in relation to a particular patient (Parsons and O'Brien 2011).

Using your intuition

Clinicians could improve their awareness of clinical decision-making: using intuition might well have a role to play, coupled with heuristics and bias—but intuition has its limitations and risks. The key disadvantages are that intuition can be difficult to justify to others or to persuade them of a course of action, and is of little or no use for inexperienced clinicians. Intuition cannot be taught, as it is experiential and vocationally-driven, not necessarily class-room acquired. Intuition can lead to misdiagnosis if the analysis of clinical evidence is displaced by instant judgements based on previous experience (Woodford 2015).

Hypothetico-deductive reasoning

However, hypothetico-deductive reasoning has a prominent place (Jensen et al. 2010) and, owing to it is robust and systematic approach to diagnosis, should be embedded into the education and everyday use of practitioners. Hypothetico-deductive reasoning can be used to rule out differentials based on patient presentation of condition, leaving the practitioner with the most likely diagnosis. This systematic approach is far safer than to rule in the diagnosis based on limited and potentially bias questioning. Specialist and advanced paramedics, underpinned by the College of Paramedic's standards of education (HCPC 2017), are establishing an emerging role within the urgent and emergency care arena. These standards provide a bench mark which the employing authority can use to support training and education (College of Paramedics 2017). These new roles are built on advanced physical assessment, clinical decision-making, and treatment options alongside wider and more in-depth education—leading to an increased scope of practice and skill base. Subsequently, out-of-hospital digit assessment and reduction may have a place in the out-of-hospital arena.

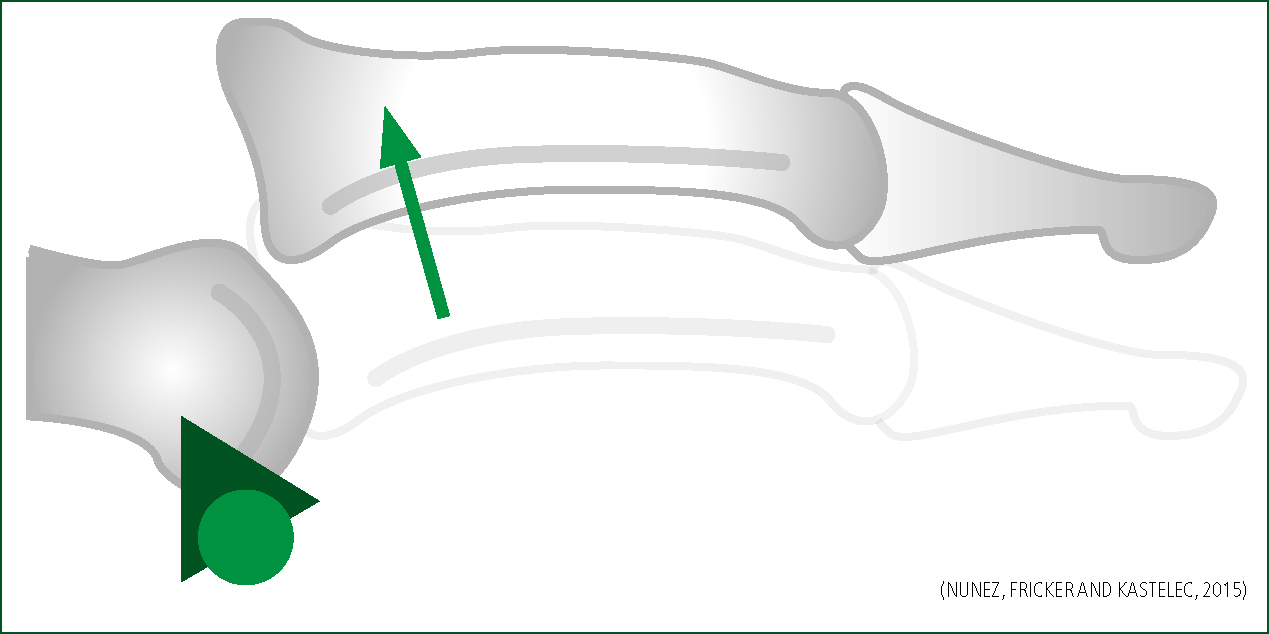

Types of dislocation

The most common dislocation of the digit is at the PIPJ (Freiberg et al. 2006; Coel 2010), also known as the ‘coach's finger’ (Brzezienski and Schneider 1995). PIPJ injuries are commonly seen in sport whereby participants are exposed to regular contact with a ball, referred to here as ball sports. This is due to hyperextension with axial loading of the digit (Rettig 2004). The PIPJ is the most common site for dislocation because of the force that is applied to the finger causing the distal and middle phalanges to act as a lever on the PIPJ (Bain and Mehta 1999; Coel 2010). The direction of dislocation is usually dorsal (Leggit and Meko 2006), as illustrated in Figure 4. Dorsal dislocation is where the middle phalanx is displaced dorsally to the proximal phalanx (Souryal and Counselman 1998). This presentation is usually reducible, traditionally in a closed manner, and is a stable presentation (Rettig 2004; Freiberg et al. 2006).

Digit and dislocation assessment

A thorough and detailed approach to examining the finger in a logical and robust manner avoids missed diagnoses, potential complications, and poor outcomes (Borchers and Best 2011). It is vital that a full history is taken from the patient before any assessment is carried out. This history starts with the event that caused the injury (Knott 2011). The mechanism of injury not only gives clues as to the forces that have been applied to the finger, but can also start clinical analysis of potential complications and red flags (Eddy 2012). Type of force, direction, speed and weight applied, if excessive, can lead the specialist or advanced practitioner to suspect deeper and more substantial injuries, which may require A&E attendance. A patient with a dislocation typically describes the injury as jamming the finger, quickly followed by pain and swelling of the joint (Finger sprains and dislocations 2013).

Eddy (2012) notes the importance of exploring previous finger dislocation; the specialist or advanced practitioner should make a comparison to the uninjured hand as part of routine assessment, but must be mindful of previous finger injuries that could lead to confusion. Considerations for the patient's occupation or sporting interests need to be explored. Finger injuries can have devastating effects on careers and daily living; the patient's profession can be related to hand dominance, and a lack of immunisation or specified boosters could have serious health complications with tetanus—as Knott (2011) states, all factors need to be considered.

It is important to observe the finger before any examination is carried out, as a skin break is indicative of an open injury, which raises the clinician's risk to a complicated injury that may require early admittance to A&E (McDevitt 1998). When examining the digits, identification of bruising and swelling are hallmark of bony injury (Eddy 2012). Colour is a benchmark observation, as cyanosis, pallor or redness can be indicative of digital nerve injury (Knott 2011), alongside skin puckering, as this can suggest interposed soft tissue within the joint capsule (Finger sprains and dislocations 2013). These are all red flags for immediate referral to the emergency department.

It is important for the specialist or advanced practitioner to identify any rotational deformity early on, as this may require surgical intervention (Eddy 2012). To assess this, fingers are viewed ‘end on’, at a flexion of 30°. Rettig (2004) explains that when undertaking the finger assessment, a number of clinical findings are sought to confirm dislocation of the PIPJ, as well as identification of potential red flags for hospital admittance. The specialist or advanced practitioner is not only looking for the obvious suspected presentations of local swelling, erythema, pain, deformity, tenderness to palpation (Rettig 2004), and an inability to move the joint (Coel 2010); he or she also needs to evaluate finger alignment, ligament integrity, neurovascular status, stability and flexion, and extension of the joints (Borchers and Best 2011). From this information, the specialist or advanced practitioner can make an informed decision as to the type of dislocation, and start to formulate an appropriate treatment plan, which may require hospital admittance.

DeBerardino (2015) discusses how assessment of the neurovascular status of the finger's digital nerves and arteries is essential before reduction is performed. This is because the use of local anaesthetic may cause complete hypoaesthesia of the finger, and consideration must be applied to the fact that reduction of dislocations can damage the nerves or vessels if not performed safely (Knott 2011). Any vascular finding suggestive of compromise needs to be reduced immediately (McDevitt 1998). Compromised vascular flow will result in tissue damage and tissue death, so time is critical with these presentations (DeBerardino 2015). Specialist or advanced practitioners should always test two-point discrimination on the finger (Lang 2003), as it is more sensitive than light-touch sensation when assessing digital nerve function (Finger sprains and dislocations 2013). If suspicion of digital nerve injury is present, the potential of digital artery damage must be suspected (Lang 2003). If the specialist or advanced practitioner is of the opinion that there is nerve damage and they have identified impairment of motor function, they would undertake a variety of specific tests that access range of movement and strength of the digits as described by Knott (2011). If the patient is unable to perform these tests, there is a high suspicion that the ulnar, median and radial nerves are damaged. Any evidence of nerve damage will require specialist assessment and repair (Knott 2011). The vascular status of the hand must be checked by feeling for the radial and ulnar pulses, and assessing capillary refill (Knott 2011). The purpose of the vascular assessments is to ascertain if blood flow is reduced to the distal digit, which could lead to tissue damage with possible permanent impact.

Reduction

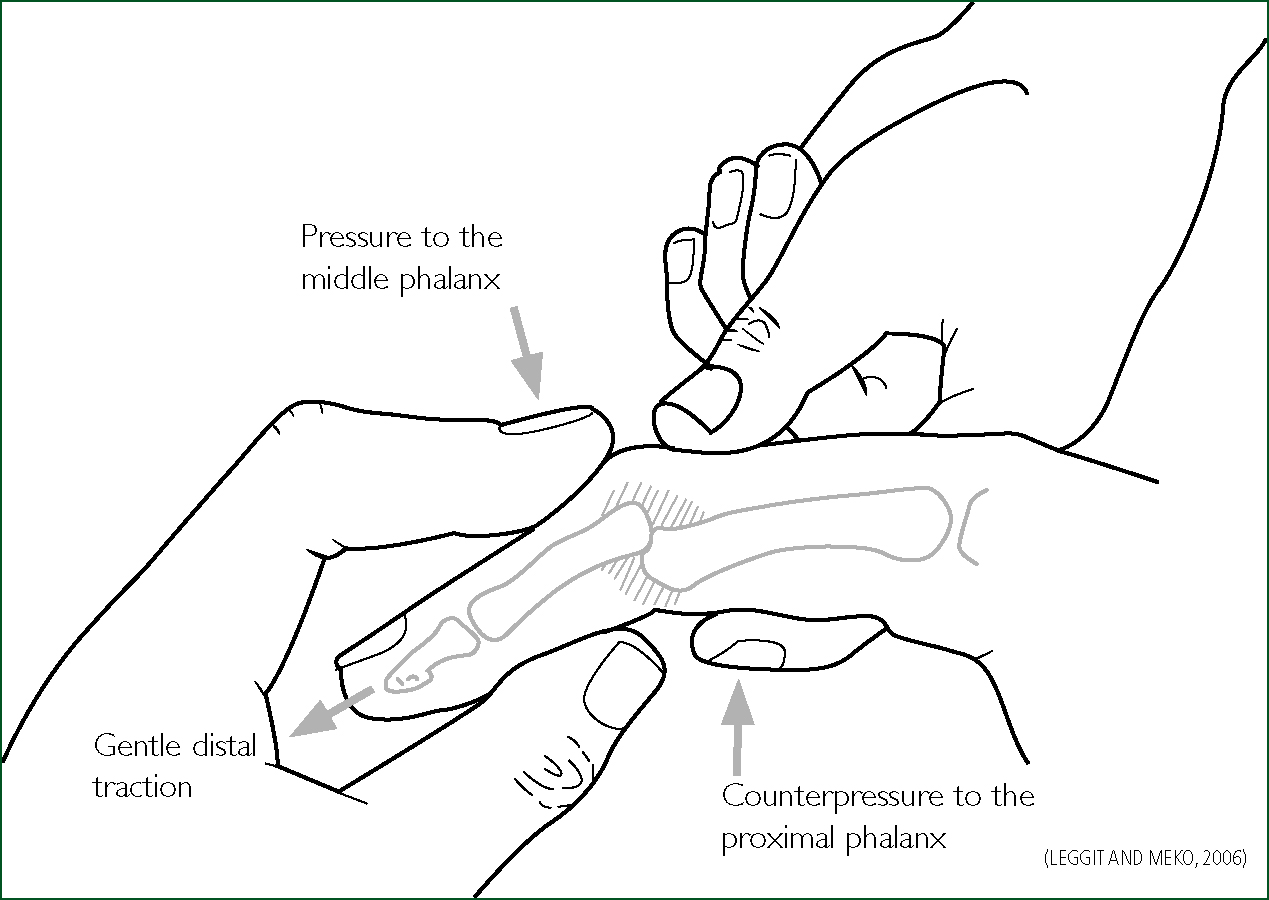

The aim of treatment for PIPJ dislocation is to restore joint congruity by closed reduction. The specialist or advanced practitioner, when reducing a dorsal presentation, should start by flexing the wrist and metacarpophalangeal joint, as this will relax the digit flexors and make reduction easier (McDevitt 1998). One hand should then be used to stabilise the proximal segment while the other hand grasps the distal displaced phalange segment firmly (McDevitt 1998). The specialist or advanced practitioner then needs to apply traction proximally to the finger using the clinician's index finger and thumb (Souryal and Counselman 1998; DeBerardino 2015). Once traction is applied, reduction should be achieved.

However, it must be remembered that manipulation at the base of the phalanx to attain a position of joint alignment while the joint is slightly flexed may be required (Souryal and Counselman 1998). The most important reduction force is the initial traction in the longitudinal direction (Lang 2003), as the use of pressure to the inline traction to facilitate reduction can cause a fracture if the phalange ends are not separated enough (McDevitt 1998). During the traction stage, the clinician applies gentle pressure to the dorsum of the base of the distal phalange (Lang 2003) in the volar (palmer) direction; simultaneously, dorsal lifting is applied to the proximal phalange (Coel 2010) bringing the distal phalanx into hyperextension (McDevitt 1998; Souryal and Counselman 1998) (Figure 5). Reduction should be obvious to the specialist or advanced practitioner when successful (McDevitt 1998) as the finger deformity disappears. However, there are always risks attached to the undertaking of digit reduction; when a dorsal PIPJ will not reduce, the patient needs an immediate referral to the A&E department (DeBerardino 2015). A plethora of evidence concludes that there is no variance for reduction technique for dorsal presentations (McDevitt 1998; Souryal and Counselman 1998; Lang 2003; Coel 2010; DeBerardino 2015).

Post reduction care

McDevitt (1998) recommends for dorsal reduced digits to be tapped to a neighbour digit at 15˚ for 7 days. This is supported by Rittig (2004) who also states that a repeat X-ray should be undertaken in five 5 days to confirm stability. Leggit and Meko (2006) and McDevitt (1998) agree that re-engagement with previous sporting activity is allowed; however, Leggit and Meko (2006) recommend digit splinting for 14–28 days. DeBerardino (2015) agrees with these treatments, but gives little guidance on the time frame of immobilisation—he continues to specify that a minimum number of joints, where possible, should be neighbour-tapped. There is consensus between the authors of the papers reviewed that neighbour-tapping is best practice to promote recovery. However, there is variance regarding the cited length of time required for tapping as a result of preferred clinician treatment plans.

Discussion

Pain management

Specialist or advanced practitioners have a wide range of appropriate pain management strategies by way of the pre-hospital pain ladder (JRCALC 2016). These may be autonomously applied depending on the level of pain relief required. Specialist or advanced practitioners must remember that the concerns and problems associated with the administration of opiate-based pain relief are considerable. These may include respiratory depression, adverse reactions, allergic complications and overdose. Furthermore, if treating the elderly, specialist or advanced practitioners must be aware of the tolerance of opiates in this age group (Simpson et al. 2012). Therefore, to avoid the use of opiate-based medication is a safer and pragmatic approach. McDevitt (1998) found that when an injury to the digit occurred, it could often be reduced with little or no anaesthetic.

This approach is generally seen at the sporting event side line undertaken by the coach in the very acute phase. This is termed and known as the ‘coach's finger injury’; seminal papers in 1974 by Hakala refer to this term being used by the sporting profession. Specialist or advanced practitioners tend not to adopt the option of just pulling the finger on the side line with minimal assessment. Johnson (1999) supports finger reduction with no pain relief, but is clear and pragmatic in acknowledging that the dislocation might not reduce easily in the acute setting, and may require specialist intervention at hospital.

Simpson et al. (2012) report that undertaking out-of-hospital reduction using a ring block and oral Penthrox is safe and successful, and can be managed with little risk. This can be taken alongside the evidence that digital nerve block is widely accepted as a safe and effective technique with few complications (O'Donnell et al. 2001)— albeit reported in the hospital setting. Digital nerve blocks have been used as a regional anaesthetic, often performed in the A&E department by advanced nurse/paramedic practitioners and doctors alike.

This point is further endorsed by DeBerardino (2015) who found that most reductions required pain relief of some description, and identified that the double-nerve block using lidocaine was the best and safest option. There are several other techniques and procedures for the administration of digit anaesthetics, such as subcutaneous volar blocks, local anaesthetic blocks, and transthecal tendon sheath blocks. However, the scope of this article does not allow for a review of these techniques.

Cannon et al. (2010) clearly explains that the (two injection) digital nerve block (TDNB) technique requires two separate injections of local anaesthetic around the four digital nerves at the base of the finger. The specialist or advanced practitioner would approach the dorsal aspect of the digit to inject local anaesthetic (Williams and Lalonde 2006) with a small needle (ideally 25 g) that will not cause excessive damage (as there is a lack of fat and tissue at the injection site). Approximately 1 ml of anaesthetic is applied to the dorsal aspect at the proximal end of the digit (Robson and Bloom 1990). This is to achieve effective drug uptake in the region of the dorsal nerve, thus giving a good anaesthetic action to allow reduction. DeBerardino (2015) describes that because digits have two sets of nerves, it is important to remember that the full effect of the anaesthetic is only gained if a further 1 ml of drug is applied by advancing the inserted needle to the volar segment of the digit.

When reviewing the use of analgesia in the digit treatment, DeBerardino (2015) found that the use of lidocaine resulted in effective anaesthesia for reducing a dislocated finger. The reason for lidocaine use as stated by Cannon et al. (2010) is that it achieved a rapid onset of pain relief and numbness, hence its position as the anaesthesia of choice for many years in standard clinical settings (2% plain lidocaine up to 5 mls per digit) (Robson and Bloom 1990). The use of lidocaine by specialist or advanced practitioners is accepted within specialist and advanced roles. Lidocaine has been used for many years in the suturing of digits.

Figure 6 shows the area of anaesthesia that is generally achieved through the use of TDNB procedure. Typically, as found by O'Donnell et al. (2001), the digit will be anaesthetised for up to 1 hour, which is adequate time for most out-of-hospital procedures.

O'Donnell et al. (2001) warns that one of the risks associated with ring blocks is sensation loss. This leads to loss of the protective reflexes of the finger, which can persist for up to 1 hour after the application, making the finger susceptible to subsequent injury. This threat of subsequent injury demonstrates the importance of post procedure care advice to the patient.

Radiographic imagery (X-ray)

Out-of-hospital reduction is supported by Rehak (2004), who notes that reduction can be attempted during the event. Rehak (2004) also advises that dislocated joints will require evaluation post reduction with an X-ray to rule out bony, ligament or tendon damage. This is supported by DeBerardino (2015), to confirm congruency of the joint and ensure that there are no associated fractures.

Simpson et al. (2012) did not undertake pre reduction X-rays. This is supported by Johnson (1999) who recognised that emergency medical technicians (EMTs) in the remote and wilderness setting scope of practice included digit reduction as long as the employing organisation allowed and indemnified for this. As for X-ray before digit reduction, McDevitt (1998) identified that clinicians were assessing patients presenting with dislocated digits at the sideline of sports games and athletic events and undertaking immediate reduction. This is based on clinical presentation and comprehensive assessment, leading the clinician to strongly suspect dislocation and, in this case, reductions prior to X-rays are recommended (Finger sprains and dislocations 2013).

Leggit and Meko (2006) support this stance, and suggest that digit reduction should be attempted without X-rays before the procedure. Borchers and Best (2011) do not agree, stating that radiographic evaluation is necessary for any suspected dislocated digit—this should include a minimum of three views (commonly anteroposterior, true lateral, and oblique). This argument is continued by Knott (2011) and Lang (2003), who are of the opinion that tendon injuries and fractures are commonly associated with dislocations and, therefore, full assessment with X-rays should be undertaken prior to reduction. There are clearly contradicting opinions and only one case reported on, which was by Simpson et al. (2012). Therefore, it is reasonable to suspect that out-of-hospital reduction before X-Ray is an unsupported practice.

Reduction

There is a distinct lack of evidence for out-of-hospital digit reduction. In fact, the evidence is too sparse for any robust argument to be built. When out-of-hospital digit reduction was undertaken by Simpson et al. (2012), it was safe and effective, and reduced well. However, there was no evidence in terms of recovery or long-term complications, so we are unable to assess whether or not this was truly a safe and effective case. It is fundamental for specialist or advanced practitioners to take a full and accurate, in-depth history, as this is key for the management to follow.

Specialist or advanced practitioners are now educated to a very high standard with solid robust education to support their improved scope of practice. It must be taken into account that paramedics in some arenas were viewed as being competent with this skill nearly 20 years ago (Johnston 1999); with advances in education, skill and practice exposure, this must now be reinforced. It must be remembered that specialist or advanced practitioners with the extended scope of practice and education base have effective pain management and assessment skills to identify and manage the dislocated digit accurately. If located in an urgent care centre, the role would involve this skill and reduction would be undertaken, but supported by X-Ray and other health professionals.

Paramedic practice, education and skill in managing patients has greatly developed since 1999. Across the UK, three-quarters of universities are now delivering paramedic education at BSc level, with specialist and advanced paramedic further education and training to postgraduate Diploma or MSc level.

Conclusion

The papers reviewed suggest that on the one occasion out-of-hospital digit reduction was undertaken by Simpson, it was safe and effective and reduced well. The concern is the limited evidence regarding recovery or long-term complications, and therefore the inability to assess if this was a safe and effective case. The suggestion is that the reduction of the PIPJ dislocation in the out-of-hospital arena is not supported owing to a lack of evidence. Until more studies are carried out and follow-up is proved to be negative and unremarkable, this skill needs to be undertaken in appropriate locations supported by X-Ray.

Recommendations

A wider case-based study is needed looking at PIPJ dislocation in the out-of-hospital arena—this needs to focus on the actions taken by the advanced/specialist paramedic compared against the post reduction recovery, and ongoing complications or issues potentially caused by the out-of-hospital reduction. This would identify whether the procedure is safe and able to be performed. The other aspect to look at would be delayed reduction from the out-of-hospital arena to see whether the delay caused any ongoing damage or issues.