Endotracheal intubation is a complex psychomotor skill, that is potentially harmful to the patient when performed by an inexperienced operator. During the past decades, attention has been focused on acquiring technical and surgical skills in safe simulation-based training environments. In addition, emphasis has been placed on transferring skills to clinical practice, such as the pre-hospital setting (Stratton et al, 1991; Owen and Plummer, 2002).

Several factors affect the transfer of skills in endotracheal intubation, such as:

Few studies have tried to identify the most effective training method in endotracheal intubation skills and the transfer of these skills to patients in clinical practice (Stewart et al, 1984; Stratton et al, 1991; Naik et al, 2001).

Pre-hospital endotracheal intubation is performed by paramedics in countries such as the UK (Lyon et al, 2010; Branding et al, 2016), and the United States (US) (Stewart et al, 1984; Stratton et al, 1991; Myers et al, 2016; Ducharme et al, 2017). In Denmark, endotracheal intubation is performed by a pre-hospital anaesthesiologist. At the time of the current study, only one anaesthesiologist-based mobile emergency care unit covered the North Denmark Region, an area of 8000 km2 and 580 000 citizens (Region Nordjylland).

The aim of the current study was to develop a simulation-based training programme on endotracheal intubation for pre-hospital paramedics using the Airtraq™ device and to evaluate the outcome of transferred skills in adult patients in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA).

Materials and methods

This quasi-experimental study was performed at the pre-hospital unit in the North Denmark Region from February 2010 to December 2012, over a total of 35 months, including the 1-month training period.

Simulation training

In groups of four or five, pre-hospital paramedics attended a 1-day 8-hour training course on intubation at the Centre for Skills Training and Simulation, Aalborg University Hospital. Training of the paramedics was conducted during a period of 1 month, and the intubation procedure skills were transferred to the pre-hospital setting upon completion of the training programme.

The programme consisted of didactic education in anatomy, respiratory physiology, and the Cormack Lehane (CL) score, followed by a demonstration of endotracheal intubation using Airtraq performed on a mannequin.

Airtraq is a disposable video laryngoscope with need of minimal neck manipulation for orotracheal intubation. Each paramedic had five attempts to perform intubation using the Airtraq in three different mannequins (Laerdal® Airway Management Trainer; METI Human Patient Simulator (HPS); and TruCorp® AirSim® Multi Airway trainer). Each paramedic had a total of 15 attempts with real-time feedback by a supervisor between each procedure. One of the mannequins (METI HPS) was placed on the floor imitating the challenging working conditions in the pre-hospital setting. Duration and outcome of each attempted intubation procedure, success or failure, were registered. Finally, the paramedics were tested in two full-scale scenarios.

The Airtraq laryngoscope, a fully disposable SP Airtraq Regular, Prodol Meditec, was chosen because it is easy to use by novice laryngoscopists (Hirabayashi et al, 2009). The laryngoscope does not require alignment of the oropharyngeal axes to obtain a good view of the glottis (Hirabayashi et al, 2008; Turkstra et al, 2009) and it has a decreased CL score compared with the Macintosh laryngoscope (Ferrando et al, 2011; Ertürk et al, 2015). Moreover, a high success rate in difficult intubations (Maharaj et al, 2008; Zadrobilek et al, 2009) and in obese patients (Castillo-Monzón et al, 2017), a high retention of skills (Mays et al, 2008), and low costs, were also favourable aspects of choosing Airtraq.

Transfer of simulation-based intubation skills to OHCA patients

All pre-hospital paramedics received comprehensive instruction and briefing on how to use the Airtraq in the pre-hospital setting. In this study, endotracheal intubation with Airtraq was only performed in adult patients in OHCA when three or more ambulance crew members were present to ensure advanced cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR); minimise hands off time; and to keep focus on time used for intubation with Airtraq.

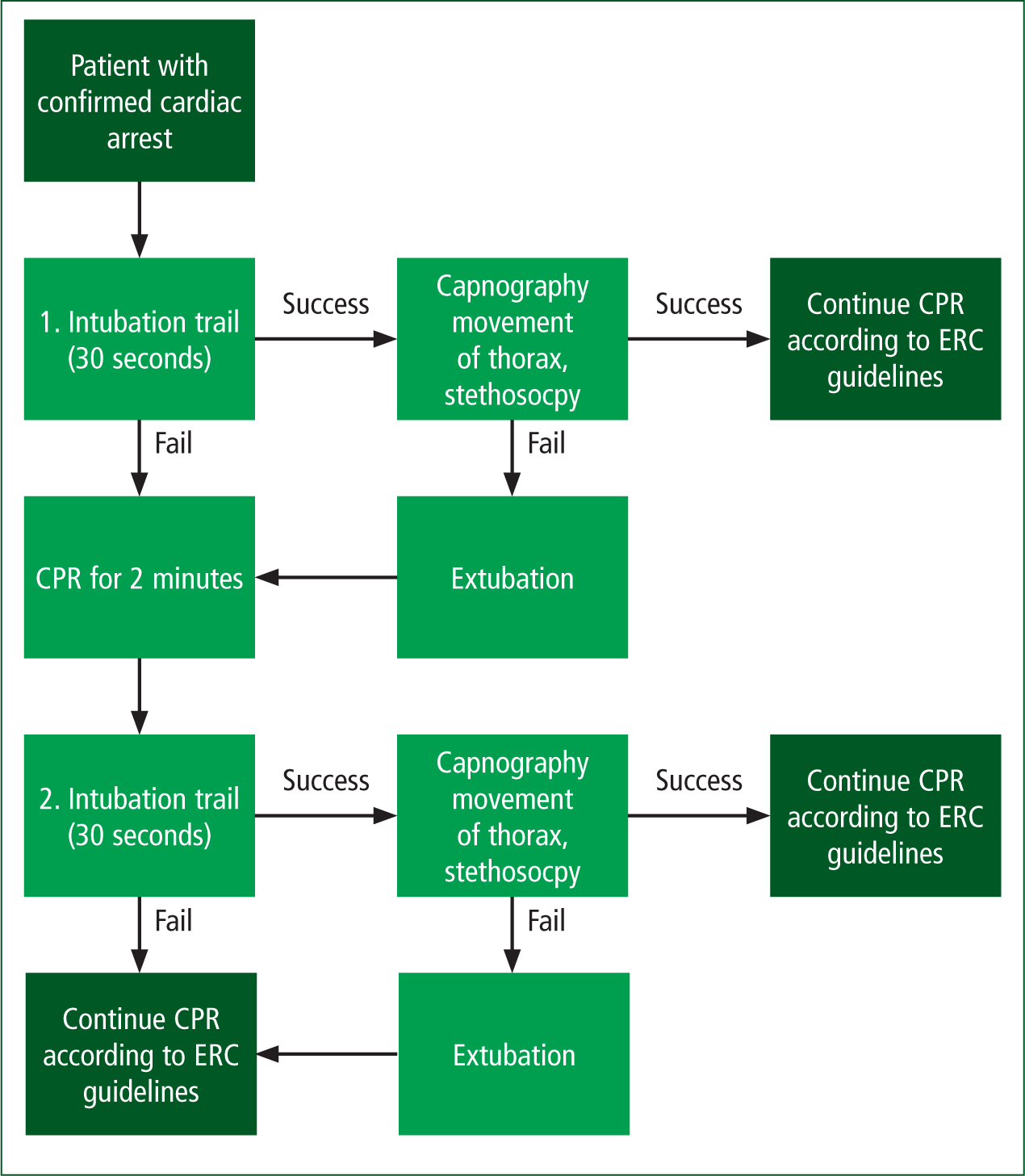

Furthermore, intubation should be performed during rhythm check while chest compression was paused and at least 2 minutes of CPR had to be performed between each attempt (Figure 1). No medication was provided for intubation. In case of aspiration, the paramedics performed upper airway suctioning. A medical doctor was not necessarily supervising the intubation procedure.

Two criteria had to be fulfilled in successful endotracheal intubation:

Verification of correct tracheal intubation was performed by end-tidal capnography, lung auscultation and bilateral movement of thorax at insufflations in accordance with European Resuscitation Council (ERC) Guidelines 2005—the most recent guidelines at the time of this study (Nolan et al, 2005). If CO2 could not be detected during ventilation or desaturation was observed, extubation should be performed and bag-valve-mask (BVM) ventilation continued to eliminate risk of unrecognised oesophageal intubation and tube displacement (Andersen and Schultz-Lebahn, 1994).

Tube placement should be controlled after every transfer of the patient. Endotracheal intubation with Airtraq was attempted consecutively in all adult patients with OHCA attended by paramedics during the study period. Patient data were recorded in the ambulance journal. Paramedics also registered study parameters in a separate registration form, designed for this study, at the end of the procedure.

Statistics

Data from the simulation training were analysed using the Student's t-test for comparison of relative frequencies. The Wilcoxon's signed rank test was used for comparison of changes in duration of intubation procedures.

Ethics

The study was approved by the Committee on Health Research Ethics in North Denmark Region (registration no. N-20102010). Informed verbal consent from each pre-hospital paramedic was required prior to participation in the study.

Results

Simulation training

Fifty-three male pre-hospital paramedics completed the intubation training course. Median age of participants was 43 years (range: 33–60) and length of employment as a paramedic was 14 years (range: 4–33). None of the paramedics had any previous experience in performing intubations.

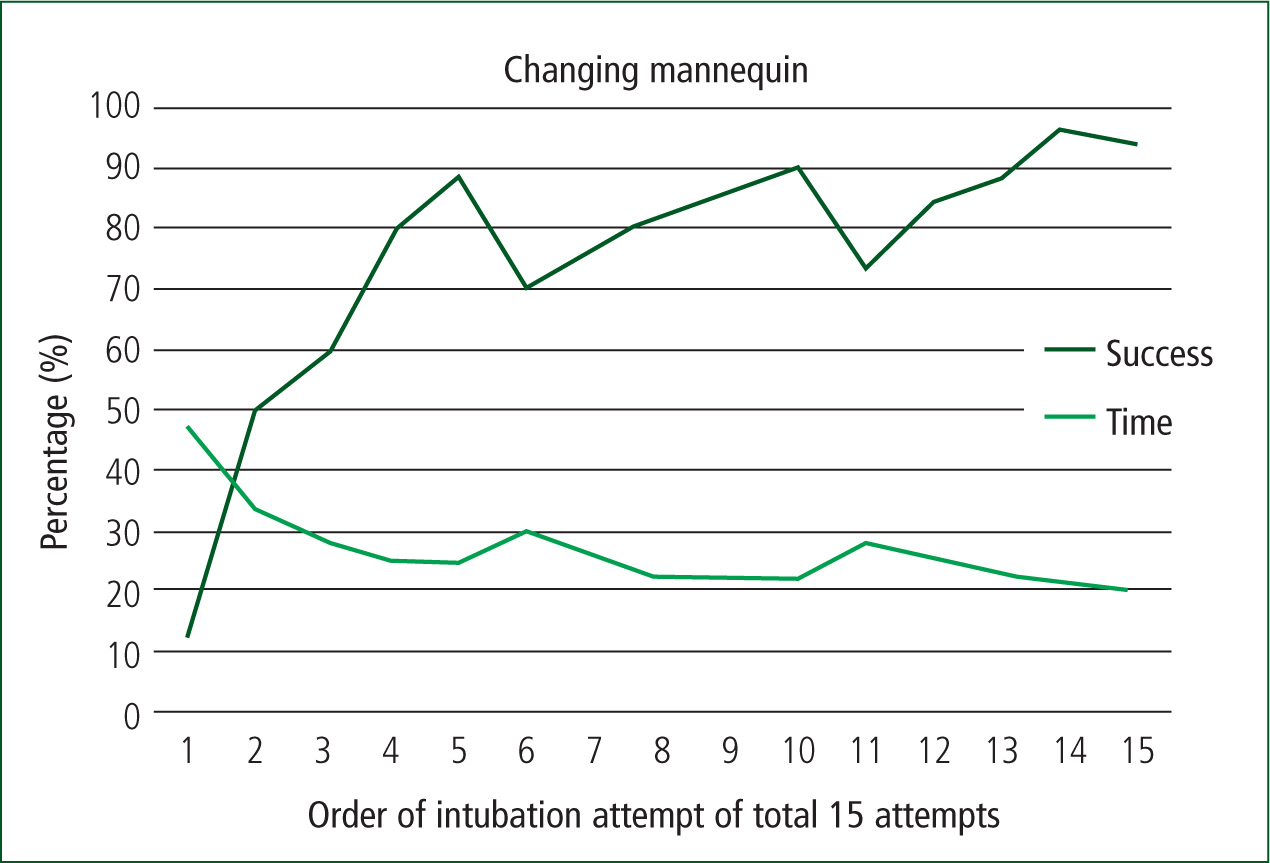

An overall improvement in intubation skills for the 53 participants was observed with the increasing number of attempts to perform endotracheal intubation. Figure 2 displays the learning curve during simulation training, demonstrating an improvement in endotracheal intubation skills among the paramedics. The overall percentage of successful intubation within 30 seconds increased significantly from 12% at first attempt to 94% at the last of the 15 attempts (P<0.0001). After the first five attempts, the success rate was 88%.

Mean procedure duration declined significantly from 47 seconds at first attempt to 20 seconds at last attempt (P<0.0001). When changing between mannequin number 1 (Laerdal Airway Management Trainer) and mannequin number 2 (METHI HPS), and subsequently between number 2 and number 3 (AirSim Multi Airway Trainer), intubation success rate declined simultaneously with an increase in procedure duration. However, this change was only brief, and intubation skills were reacquired fast. In the final two full-scale scenarios, all paramedics performed successful intubation within 30 seconds.

Transfer of intubation skills to OHCA

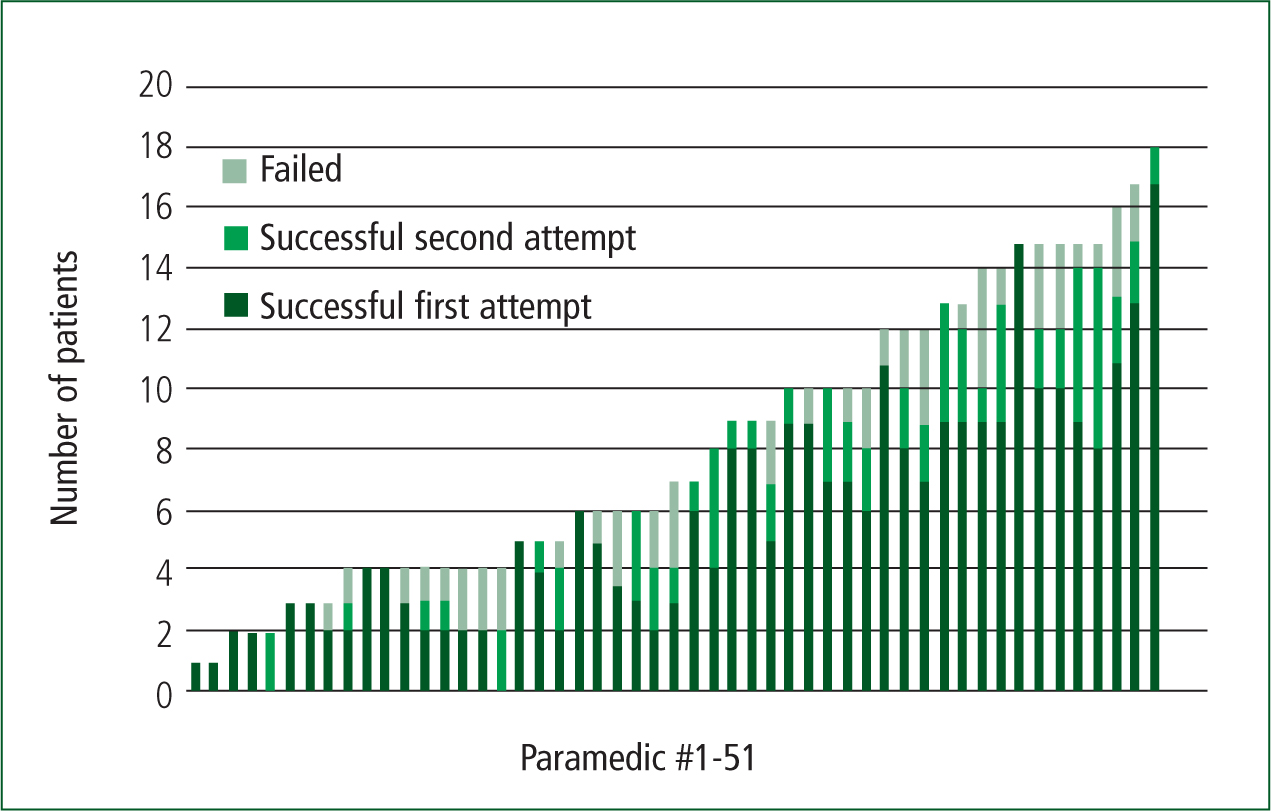

During the 35-month study period, endotracheal intubation was performed in 417 patients with OHCA by 51 (96%) of the 53 paramedics attending the simulation training course.

Intubation was performed successfully in 366 (88%) of the 417 patients; 296 (81%) were intubated in the first attempt and 70 (19%) in the second attempt. In three successful intubation procedures, the 30-second time limit was, however, exceeded by 1, 10 and 15 seconds respectively.

In 51 patients (12%), the second intubation attempt failed and airway was managed by BVM ventilation. According to the paramedics, the leading causes of failed intubation were aspiration, airway secretion and high CL score. Other causes of failed intubation were reported to be obesity; pathological airway due to drowning or hanging; tube displacement; oesophagus intubation recognised during the procedure; defective equipment; lack of end-tidal capnography; exceeded time limit; or the patient was resuscitated and returned to spontaneous respiration. In 19 patients, it was unclear why intubation had failed (there was no description available on the study registration form). The overall distribution of reasons for failed intubation is shown in Table 1.

| Reasons for failed intubation | Failure of 1st attempt, successful 2nd attempt | Failure of 1st and 2nd attempt | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aspiration or airway secretion | 30 (43%) | 26 (51%) | 56 |

| CL score 3-4 | 14 (20%) | 14 (27%) | 28 |

| Obesity | 4 (6%) | 5 (10%) | 9 |

| Pathological airways | 3 (4%) | 6 (12%) | 9 |

| Intubation of oesophagus | 3 (4%) | 3 (6%) | 6 |

| Tube displacement | 3 (4%) | 2 (4%) | 5 |

| Defective tube | 1 (1%) | 0 | 1 |

| According to algorithm | 0 | 11 (22%) | 11 |

| Patient was resuscitated | 0 | 2 (4%) | 2 |

| Unclear reason (no description) | 19 (27%) | 4 (8%) | 23 |

| Total | 77 | 73 | 150 |

1–3 reasons for failed intubation were registered on the registration forms

Fifty-one of the 53 participating paramedics performed endotracheal intubation in an average of eight patients with OHCA (range: 1–18) during the study period (Figure 3). Among the 51 patients with OHCA where intubation failed in the second attempt, a majority of 73% (n=37) occurred among paramedics performing their first five intubation procedures. Moreover, intubation success rate increased significantly in accordance with the total number of procedures performed by the individual paramedic: 86% (1–10 intubations) vs. 97% (11 intubations) (P=0.004).

The CL scores (I-IV) among the 417 patients were registered as follows:

In 70 patients, the CL score had not been registered and intubation had failed in 30 of these patients.

Criteria for successful endotracheal intubation were registered as fulfilled in 99% (n=361) by auscultation, in 99% (n=361) by movement of thorax and in 90% (n=329) by capnography. In the 10% (n=37) without CO2 detection, treatment was terminated right after intubation before capnography was applied in five patients.

An anaesthesiologist on scene verified tube placement in 17 patients; in 15 patients, no reason for the lack of capnography was recorded. Oesophageal intubation was registered in relation to intubation in six patients and the patients were extubated immediately on scene. Upon arrival at the emergency department (ED), no oesophageal intubation was registered. No adverse events related to endotracheal intubation with Airtraq were registered and no dental injuries were reported.

Discussion

The current study showed that endotracheal intubation in OHCA patients was performed safely by paramedics after attending a 1-day simulation training course in intubation with Airtraq. The out-of-hospital endotracheal intubation success rate of 88% (71% in the first attempt; 17% in the second attempt) in our study is comparable with Airtraq intubation success rates between 47–82% (Trimmel et al, 2011; Russi et al, 2013; Gellerfors et al, 2014; Selde et al, 2014) and pre-hospital intubation with direct laryngoscopy and a success rate between 74–99% (Stewart et al, 1984; Stratton et al, 1991; Wang et al, 2001; Lyon et al, 2010; Trimmel et al, 2011; Selde et al, 2014) reported in other studies.

Simulation training using multiple airway mannequins has been suggested to be better than multiple attempts on the same type of mannequin (Owen and Plummer, 2002), with decreasing success rate when changing between airway trainers (Plummer and Owen, 2001; Wong et al, 2011); this was also observed in the current study. Change between mannequins may reflect the differences in anatomy in real-life patients in a safe simulation environment. However, mannequins still differ from humans in many aspects, which is important when transferring acquired intubation skills from a simulation setting to clinical practice (Hesselfeldt et al, 2005). Intubation was not performed on real-life patients between the 1-day training programme and first out-of-hospital intubation event, which was similar to other studies (Stratton et al, 1991; Russi et al, 2013). Paramedics in the current study had extensive non-invasive airway management skills prior to the study, which may have positively impacted their learning (Owen and Plummer, 2002).

Airtraq device and guidelines

In the current study, the Airtraq device proved to be an easy-to-use and safe instrument for endotracheal intubation by novice laryngoscopists. Since the paramedics in the current study had no previous intubation experience, as Danish paramedics are not normally trained in intubation or any form of infraglottic airway device, there was no previously acquired intubation technique that needed to be modified.

Paused chest compression for up to 30 seconds during intubation may improve intubation conditions compared with intubation during chest compressions. At the time of the current study, the ERC guidelines stated that laryngoscopy should be performed during chest compressions with a brief pause of no more than 30 seconds for passing the tube through the vocal cords (Nolan et al, 2005).

Current ERC guidelines from 2015 have less emphasis on intubation and state that the intubation attempt should interrupt chest compression for less than 5 seconds; otherwise, BMV ventilation is recommended (Soar et al, 2015). No new data support the routine use of any specific airway management during cardiac arrest. Risk and benefits of intubation need to be weighed against the need to provide effective chest compression. The best technique depends on the precise circumstances of the OHCA and the competencies of the paramedic. Evidence of whether intubation has a better neurological and survival outcome is lacking (Soar et al, 2015).

Failure of intubation with Airtraq in the above mentioned studies (Trimmel et al, 2011; Russi et al, 2013) was primarily ascribed to airway secretion. Similarly, aspiration, airway secretion and a high CL score were high-risk predictors of failed intubation in our study. It is known that aspiration and secretion impair the vision with video laryngoscopes (Trimmel et al, 2011; Russi et al, 2013), even if suctioning is performed, which influences successful intubation negatively.

Cormack Lehane score

Secretions in the airway are difficult to simulate during simulation on mannequins. Possible explanations for attempting a second intubation could also be insecurity, difficulties with the technique or little experience. Although the CL score was originally developed for direct laryngoscopy, the authors used it to describe visualising the airway, keeping in mind the viewing lens is situated near the larynx with a larger angle of 50–60°.

The CL score is not easy to use with a video laryngoscope and the paramedics do not routinely use the CL score, which may influence reliability of the score in this study. Many patients with a CL score of 3–4 were intubated at the first attempt.

Intubation procedure

In 37 patients, capnography was not applied; this is not in compliance with the protocol. Despite movement of thorax and auscultation, oesophageal intubation constitutes a risk (Andersen and Schultz-Lebahn, 1994) and the patients should have been extubated. In these cases, the paramedics described clinical signs that convinced them that the tube was placed in the trachea, a patient history of possible lack of circulation despite CPR, termination of pre-hospital treatment and verification by a doctor.

During the study, the importance of capnography was explained to the paramedics. The risk of unrecognised oesophageal intubation, such as a lack of oxygen delivery, is one of the reasons the ERC guidelines recommend that intubation should be performed by experienced, highly skilled and trained medical staff (Soar et al, 2015).

The intubation procedure was new and complex to the paramedics and perception of time was challenged. When focusing on new and complex procedures, it is easy to lose track of time, especially when you need to multitask during cardiac arrest treatment. This might contribute to the exceeded time limit by 30 seconds for intubation in three patients in the current study. Prolonged attempts at endotracheal intubation may be harmful because cessation of chest compressions during this time further compromises coronary and cerebral perfusion. The intubation attempt should have been stopped and BVM ventilation continued. These three intubation attempts exceeding the time limit should have been registered as failed by the paramedics.

In the pre-hospital setting

The stressful working environment and often challenging work positions, e.g. at the floor in a pre-hospital setting, makes airway handling more difficult compared with an in-hospital setting. A stressful environment has been suggested to influence transfer from simulation training to clinical practice in studies within the field of surgery (Prabhu et al, 2010; Yurko et al, 2010).

However, the current results showed a high success rate in the pre-hospital setting, even though some paramedics only performed a low number of intubations throughout the study period of almost 3 years. It could be expected that skills decline over time when not performed in real-life clinical practice; this did not seem to be the case in the current study. Wang et al (2005) suggested there is no relation between time elapsed from first patient intubation and the success of following intubations.

Data and limitations

All pre-hospital paramedics in the North Denmark Region were included in the study and they performed endotracheal intubation consecutively in all adult patients with OHCA, limiting selection bias.

Use of the Objective Structured Assessment of Technical Skills (OSATS) consisting of a global rating scale and a checklist (Naik et al, 2001; Hamstra, 2005) or a more specific Airway Management Proficiency Checklist (AMPC) for paramedics may further improve intubation skills in future training programmes (Way et al, 2017).

Moreover, registration of intubation attempts and duration of the two full-scale scenarios was important to evaluate skills of the paramedics during simulated stressful work conditions. All data were self-registered by the paramedic performing the endotracheal intubation, which may cause registration bias. A weakness of the current study is the low number of intubations performed for most of the participating paramedics.

If the study was reproduced today, it would be according to recommendations in the new ERC guidelines from 2015 (Soar et al, 2015). This means the algorithm would be laryngoscopy with Airtraq during ongoing CPR, with tube passage of the vocal cords during control of cardiac rhythm for a maximum 5 seconds to ensure continuous CPR. A transportable capnography for application right after intubation should be available, and extubation should be consistent when no CO2 detection was registered or a time limit of 5 seconds was exceeded. Most failed intubation attempts occurred within the first five attempts, which suggests benefit of supervision on scene by an anaesthesiologist during the first intubation attempts or an extension of the training programme with in-hospital training, e.g. in the operating theatre.

Regular update of skills and recertification could be ways to secure retention of sufficient skills. Current ERC guidelines from 2015 suggest that medical staff performing intubation during cardiac arrest should be part of a monitored programme including comprehensive competency-based training with regular opportunities to update skills (Soar et al, 2015). Further research is needed to investigate the possible effects of such recommendations.

Conclusion

The current study suggests that endotracheal intubation with Airtraq can be learned with a simple simulation-only training programme using different airway trainers. Airtraq laryngoscope proved to be an easy-to-use and safe instrument for intubation in practitioners with no previous intubation experience. Transfer of skills from simulation training to clinical practice needs to be further explored. The new ERC guidelines from 2015 have less emphasis on airway management; there is no evidence that endotracheal intubation correlates with a better outcome.