It is difficult to assess the prevalence of scabies with any degree of accuracy as it is a condition that is often misdiagnosed or tends to be treated without medical or nursing consultation (Gould, 2010). It is highly contagious and its timely identification will help not only the patient themselves but should also limit transmission. Despite the stigma surrounding scabies, it is a condition that has no preference for age, sex, ethnic or socioeconomic group (Chosidow, 2006). It is not linked to poor hygiene since scabies mites are resistant to soap and hot water (Heukelbach and Feldmeier, 2006).

The scabies mite is an obligate parasite and causes an infestation rather than an infection (Gould, 2010), although secondary infection may occur as a result of infestation. The particular variety is named according to its host, Sarcoptes scabiei var hominis, and most commonly affects humans (Strong and Johnstone, 2007). Although it is possible to catch different varieties from animals, these tend to be limited to the area in contact with the animal and self-limiting in nature, requiring no treatment (Heukelbach and Feldmeier, 2006).

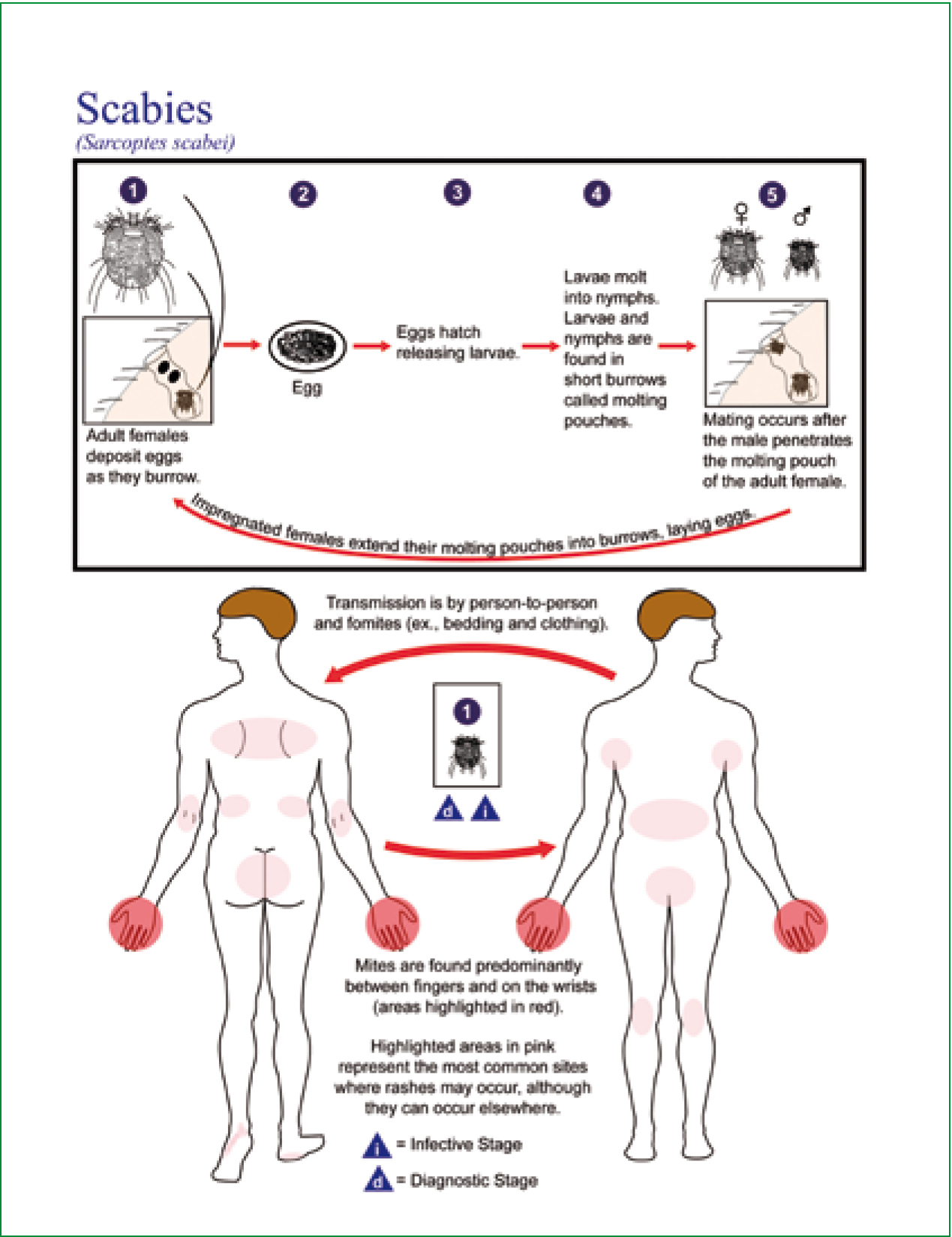

Having an understanding of the presentation, methods of transmission and treatment of scabies, may prepare the paramedic who comes across it in practice and alert them to make a thorough assessment of not only the patient but also their cohabitants within the community setting (Figure 1).

This case study is set in a walk-in centre but is transferable to the prehospital setting in which it may be easier to complete a more thorough investigation. While symptoms such as itching or rash may not, in themselves, be considered an emergency warranting an ambulance response, the paramedic caseload is extremely diverse and patients often present with co-morbidities (Fellows and Woolcock, 2008). For this reason, paramedics would benefit from having an index of suspicion when encountering such symptoms.

Signs and symptoms

Mrs C presented to the walk-in centre complaining of intense itching associated with rash, which worsened at night (Appendix). The patient also revealed that she felt an intense itch in the flexor surface of her elbow but had found no rash. Scabies should be suspected in any patient presenting with a rash and intense pruritus, especially if the pruritus worsens at night (Fawcett, 2003).

In order to support this diagnosis, it was necessary to inspect the rash and note the character of the lesions, colour, texture and distribution. Discrete punctate erythematous papules were found, most of which were excoriated due to scratching.

What was not evident, which would have afforded a definitive diagnosis, was a burrow. This would have appeared as a tortuous, scaly line on the surface of the skin (up to 10 mm long), at the end of which may have been a minute papule or vesicle (Johnston and Sladden, 2005; Cross and Rimmer, 2007).

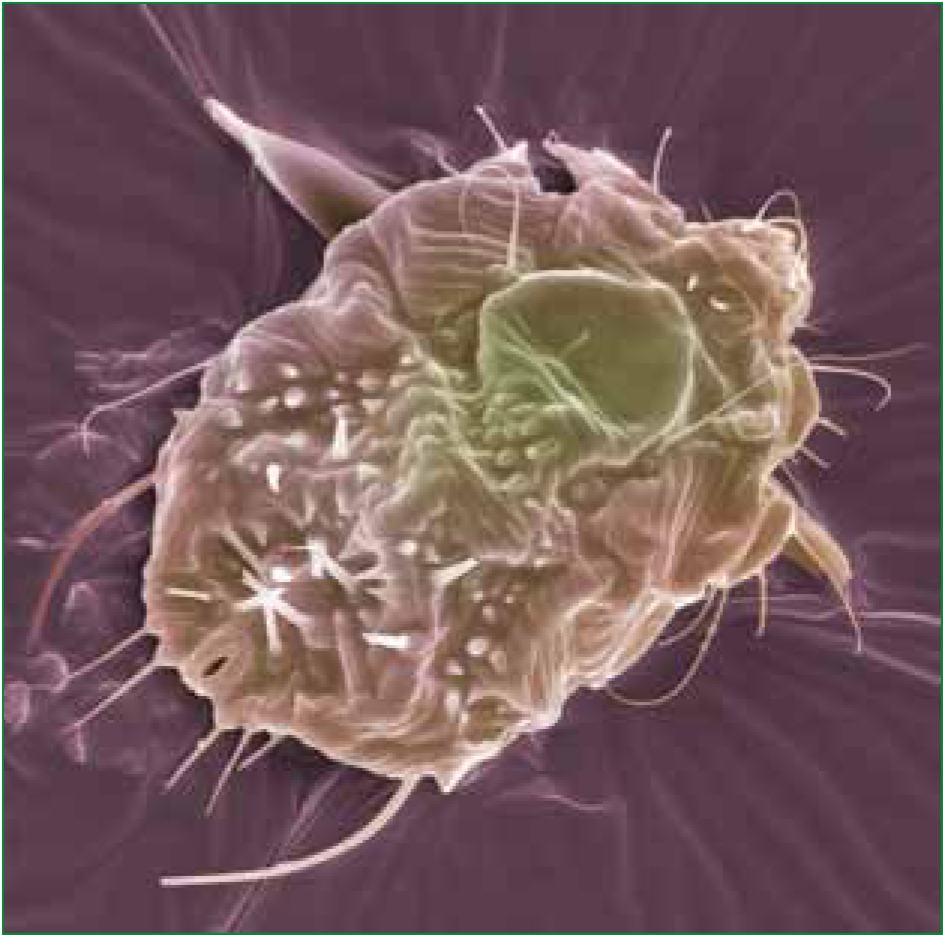

The skin lesions associated with scabies are multiform—papules, which may progress to vesicles or pustules, and nodules on the male genitals; with crusted lesions in the immunocompromised (Fawcett, 2003; Tan and Goh, 2001; Johnston and Sladden, 2005). Papules may change into vesicles and bullae, and may develop into secondary lesions such as excoriations, eczematisations, and crusts (Heukelbach and Feldmeier, 2006). This makes the burrow the ‘gold standard’ lesion by which to diagnose scabies. The mites themselves are too small to be seen easily with the naked eye, with females measuring 0.4 mm and males 0.2 mm in length (Gould, 2010).

In this case, the diagnosis was based largely on key findings in the health history. Gold standard diagnosis is often thought to be via microscopy of skin scrapings, whereupon mites, their ova or faeces may be identified (Cresswell and Stratman, 2007), although this method has been found to have low sensitivity as a diagnostic tool—even though it has high specificity (Heukelbach and Feldmeier, 2006).

However, such techniques are not available to the paramedic in the field. Although burrows are possible to identify with the naked eye, they are often destroyed by bathing or scratching (Heukelbach and Feldmeier, 2006). Diagnosis must therefore involve taking a good history.

This case highlights the importance of good history taking. Having established that the patient's condition does not constitute an emergency, the approach can be more thorough. In the emergency situation, we often find ourselves questioning the patient, while physically examining or treating them. This approach is unnecessary and detrimental in the context of minor illness. It might have been easy to arrive at the wrong diagnosis in this case had the history-taking been rushed since the physical examination suggested differential diagnoses such as eczema, insect bites and impetigo (Cross and Rimmer, 2007).

Each would present with a different history, although eczema may be found in scabies-infested patients as a result of the patient's immune response (Johnston and Sladden, 2005). Scabies should, however, be considered in newly presenting eczema or an acute exacerbation in a pre-existing sufferer.

Social morbidity associated with scabies

A diagnosis of scabies is likely to have implications of social morbidity for a patient (Tan and Goh, 2001). This was borne out by the look of horror on the patient's face as she realized that this annoying itch was due to an infestation of mites. The itching is not, as is commonly believed, due to the burrowing action of the mites. The signs and symptoms of scabies are caused by a reaction to the mites, eggs and faecal products (Flinders and de Schweinitz, 2004).

‘A diagnosis of scabies is likely to have implications of social morbidity for a patient’

The patient's angst grew as she questioned what she was going to tell her friends with whom she was currently residing. Due to the method of transmission, this would be unavoidable. Scabies mites are passed from person to person by close contact. For this reason, it is common for scabies to spread in close communities such as a nursing home or densely populated accommodation (Gould, 2010). They are attracted to a new host by odour and heat (Heukelbach and Feldmeier, 2006). Scabies mites crawl at a rate of 2.5 cm per minute on warm skin (Chosidow, 2006) and so brief contacts, such as shaking hands, are less likely to result in transmission of the mites than prolonged contacts (Gould, 2010). It is common for transmission to occur as a result of sexual contact and for this reason patients with scabies should also be advised to be tested for sexually transmitted infection (Gould, 2010).

Once present on the skin, it is only the female that burrows. Males die after mating but the newly mated female dissolves the stratum corneum of the epidermis with proteolytic secretions (Chosido 2006). She then burrows into the skin between the dermis and epidermis to lay eggs at a rate of 2-3 per day for up to 2 months. The eggs hatch after 3-4 days, grow and shed their skin. They then leave their burrows and move to the surface to mate (Gould, 2010).

‘Hyperinfestation may occur in crusted scabies which make the sufferer highly contagious. Mite numbers may exceed a million in such cases and skin may become hyperkeratotic with a crusted appearance’

Transmission

Since the patient had been in close contact with her friends over the past few days, it was possible that they may already have been infested. The first time a patient becomes infested with mites, the reaction is delayed. It may take between two and six weeks for symptoms to appear (Gould, 2010). During this time, the mites may be passed on to others (Currie and Mccarthy, 2010). Therefore, this patient's friends may already have been infested and not yet realized. On this first occasion of infestation, the patient becomes sensitized. Subsequent episodes will trigger the adaptive immune response and symptoms will appear within a day (Heukelbach and Feldmeier, 2006).

Advice surrounding fomites is contentious. The fact that live mites have been found on the soft furnishings of patients infested with scabies is sufficient to lead some authors to advocate the washing of clothes and bed linen at 60 °C, and application of powder insecticides to non-washable soft furnishings (Chosidow, 2006). Others state that fomite transmission is uncommon (Currie and McCarthy, 2010), while the Health Protection Agency (HPA) specify that fomites may contribute to the spread of hyperkeratotic scabies (HPA, 2010). It is considered rare for fomite transmission to be implicated in classic scabies (Gould, 2010).

Infestation may present as classic scabies in patients with normal immune status or hyperkeratotic (crusted) scabies in those with immature or impaired immune status (Gould, 2010). In classic scabies infestations, mite numbers usually range between ten and fifteen. Hyperinfestation may occur in crusted scabies which make the sufferer highly contagious (Gould, 2010). Mite numbers may exceed a million in such cases and skin may become hyperkeratotic with a crusted appearance (Strong and Johnstone, 2007). Itching may be mild due to these skin changes.

As well as a stigmatized diagnosis, the treatment of scabies may cause the patient further embarrassment, as was the case with Mrs C. Unfortunately, this is not a simple oral remedy but involves whole body application of a topical scabicide, twice with seven days between applications. This is because permethrin is not an ovacide and so eggs may survive the first treatment and develop to maturity. Some authors recommend that the head and neck should not be covered, since scabies mites do not infest these areas (Johnston and Sladden, 2005); however the British National Formulary (BNF) is careful to state that treatment should include scalp, neck, face and ears (BNF, 2007).

It is argued that permethrin should be applied to all areas of the body, except the eyes, because scalp and face are often involved in young children and the elderly (Currie and Mccarthy, 2010). To ensure complete coverage, the patient would need to enlist the help of a friend. This suggestion visibly troubled the patient in this case. Physical difficulty is a contributory factor in poor treatment concordance (BNF, 2007) and so anticipating this difficulty and suggesting a method of overcoming it increases the likelihood of a successful outcome. Emphasis of the benefits and effectiveness of treatment are important in improving concordance (Cross and Rimmer, 2007).

Scabies is annoying and embarrassing. Its treatment is inconvenient and unpleasant. For the patient, it would be important to understand that it was worth putting up with the additional embarrassment and inconvenience of treatment. For the clinician, concordance with treatment regime might be more likely, reducing the likelihood of a repeat consultation.

Clarity of treatment instructions is also important (BNF, 2007), but given the psychological impact of receiving a scabies diagnosis, more than clarity may be required. In the Calgary-Cambridge Guide to the Medical Interview, various measures are suggested to aid the understanding and recall of information (Silverman et al, 1998).

In this case, key information was presented verbally in easily understood language, repeated and also presented in written form for the patient to take away. The patient was also made aware that itching would likely persist for two to three weeks post-treatment; this was not an indication of treatment failure but due to a reaction to the antigens of the killed scabies mites (Tomalik-Scharte et al, 2005).

Given the difficulty in accurately diagnosing scabies, it might be argued that the negative psychological impact of receiving this diagnosis and subsequently having to inform close contacts and undergoing treatment demands a more rigorous approach to diagnosis. A secondary effect of scabies is sleep deprivation, due to the itch which in turn can lead to low mood and the pruritus being viewed in more negative terms.

Treatment

Current first choice treatment is permethrin 5% dermal cream, with malathion 0.5% aqueous lotion recommended as second choice (NHS Clinical Knowledge Summaries, 2008). Permethrin is neurotoxic to invertebrates and disrupts neural transmission by altering the voltage-gated sodium channels of nerve cell membranes prolonging depolarization (Currie and McCarthy, 2010). This has superceded drugs such as lindane which has been associated with neurotoxic effects such as anxiety and seizures. If ingested, lindane has been found to cause respiratory paralysis and circulatory collapse (Roos et al, 2001).

In a small-scale study of permethrin cream, Tomalik-Scharte et al (2005) found that only a very small fraction of the amount applied is absorbed through the skin. However, despite the claims of safety made by this study, the sample size is extremely small (n=12) and so generalization of results is problematic. Prescribers should be careful to ensure that patients receive the correct formulation (Cox, 2000). Several patients who presented as a result of permethrin treatment failure were found to have been using the 1% lotion intended for use on head lice, rather than the 5% cream for scabies.

Not only are the strengths of the formulations different but instructions on their packaging will differ. The dermal cream should remain on the skin for 8-12 hours, whereas the scalp lotion is applied for 10 minutes. Due to the length of time required, it is suggested that dermal cream is applied prior to going to bed and washed off the following morning. Infants should wear gloves to prevent sucking the cream off their hands (Gould, 2010). Treatment of crusted scabies with topical creams should be augmented with a keratolytic agent. This will break down skin crusts, optimizing the action of the scabicide (Currie and McCarthy, 2010).

Malathion is an irreversible cholinesterase inhibitor (Tan and Goh, 2001). This leads to increased cholinergic transmission since the enzyme cholinesterase is unable to break down the neurotransmitter acetylcholine (Ach) in the synapse. Since this action is irreversible, the effects continue and ACh activity is enhanced, resulting in a fatal neuromuscular block (Rang et al, 2007). Malathion is deactivated quickly in human plasma but not in that of insects (Tan and Goh, 2001)—although fatal to the scabies mite, it is not to their human hosts.

Although well-tolerated, there is the potential for skin absorption which may lead to respiratory distress, gastrointestinal disturbance and headache (Tan and Goh, 2001). Its use is based on the results of a non-controlled study; there are no randomly controlled trials comparing malathion with either permethrin or placebo (Strong and Johnstone, 2007). Its being second choice is probably based on its comparative clinical safety.

New treatments

An emerging oral treatment is ivermectin which has been used since 1990 as a broad-spectrum antiparisitic (Rang et al, 2007). It acts by blocking glutamate-gated or GABA-gated channels in the nerve-muscle synapses of arthropods and insects (Dourmishev et al, 2005). This paralyses them, leading to death. Its efficacy has been found to range from 73-98% (Fawcett, 2003). In a randomized controlled trial, a single dose of topical 5% permethrin was compared with a single dose (200 mcg/kg) of oral ivermectin in treating scabies patients. At one week, fewer patients had responded to ivermectin (70%) than permethrin (97.8%) and a second dose of each was administered at two weeks.

At four and eight weeks, there was no significant difference in response to each treatment (Usha et al, 2000). However, this study does not follow the recommended treatment regime for permethrin (two applications, seven days apart) or with BNF recommendations of a single dose of ivermectin in combination with topical scabicides (BNF, 2007). Dourmishev et al (2005) suggest giving two doses of ivermectin seven days apart due to its lack of ovocidal action. Mild reactions to ivermectin have been reported such as rashes and pruritus, but this is thought to be a reaction to the dying mites (Dourmishev et al, 2005). Very few severe adverse reactions have been reported.

Although ivermectin in single dose was not found to be as effective as permethrin (Usha et al, 2000), there are situations where it would be more practical. It is not possible to effectively apply a topical scabicide to the whole body oneself. For the patient who lives alone, the prospect of asking someone to apply a scabies treatment to their skin may be so daunting that non-concordance is the most likely outcome.

If a patient lacked mental capacity, they may not allow a full topical application or may not leave it on for the required time. For such patients, oral ivermectin may be the preferred treatment option. Currently in the UK, it is only available as a single dose on a named patient basis for the treatment of hyperkeratotic (crusted/Norwegian) scabies (BNF, 2007). It may become more readily available in the future when large scale assessment of effectiveness and cost-effectiveness has been undertaken (Strong and Johnstone, 2007).

It is likely that Mrs C would have opted for ivermectin had she have been given the choice. This would be a more palatable treatment option and less demanding on her close contacts. This may also lead to the diagnosis of scabies being more readily made which in turn would probably reduce infestation rates.

In addition to scabicidal treatments, patients with severe itch may require antipruritic treatment and those with secondary bacterial infections may require antibiotic treatment (Gould, 2010). Whichever treatment regime is applied, patients and their contacts should be followed up for around a month. This timeframe is sufficient— either for lesions to heal or for surviving mites to grow and mature sufficiently to create new burrow that may be identifiable (Currie and McCarthy, 2010).

When dealing with patients suffering with scabies, the wearing of gloves and good hand washing technique should protect the paramedic; while linen should be hot washed after use by an infested patient (Fellows and Woolcock, 2008).

Conclusion

This case study presented some of the common signs and symptoms of classic scabies, as well as highlighting some of the social and psychological issues raised by the condition. Pruritis, especially at night time, and an erythematous rash in the web spaces of fingers and toes, wrists, elbows and buttocks are highly suggestive of scabies infestation. Identification of a burrow would confirm the diagnosis.

A good history should be taken and close contacts identified and informed in order that they may be assessed and treatment started if appropriate. Permethrin is the current treatment of choice and requires application twice in order to deliver optimal scabicidal effect. Other concomitant treatments may also be required depending on the particular needs of the patient. The condition is highly contagious but the paramedic may be protected by taking simple precautions.

Scabies remains a highly stigmatized condition and infested patients require careful handling in terms of providing good information and reassurance if they are to correctly follow the treatment regime.