Spinal immobilisation: still uncertain?

In this paper, the authors argue that spinal immobilisation during extrication of patients in road traffic collisions (RTC) is still routinely practised, despite the lack of evidence. The current research builds upon a previous ‘Proof of Concept’ study undertaken by this team (Dixon et al, 2014), which identified up to four times more cervical spine movement when using traditional rescue equipment, as opposed to allowing haemodynamically stable patients to self-extricate under paramedic instruction.

Using biomechanical analysis, the most recent study sets out to identify which technique used during extrication from a vehicle causes the least cervical spinal deviation from the neutral in-line position.

Sixteen participants were recruited: seven males and nine females, aged between 18–40 years (mean age 24 years), height between 157–198 cm (mean=174 cm); five participants weighed under 65 kg, six people were in the 65–80 kg category, and five weighed over 80 kg. Participants were excluded if they were under 18 years, already had knowledge of extrication procedures and/or they had medical conditions that may be aggravated by extrication such as spinal injuries, arthritis etc.

Crews comprised four members of the fire service and two members of the ambulance service, which reflected standard deployment to RTCs in that geographical region. They were fully trained in manual handling procedures and the equipment used in the study.

Reflective markers were placed on participants, enabling measurement of flexion, extension and rotation of the cervical spine, and movements were captured using three-dimensional motional cameras.

Each participant was exposed to six techniques for extrication, and the starting point for all scenarios involved the participant sitting face forward in the driver seat of the test vehicle. Techniques included: participant self-extrication under paramedic instruction, participant exits car under own volition having been fitted with cervical collar and receives manual c-spine stabilisation, participant has cervical collar applied and is extricated on a long spinal board (LSB) through rear window, participant has cervical collar applied and is rotated 90° to driver door side and extricated on the LSB head first through passenger door, participant has cervical collar applied and is rotated 90° to passenger side and extricated on the LSB through the driver's door, participant is fitted with a cervical collar, immobilised with a short extrication jacket (SEJ) and lifted through the driver's door without any rotation.

Results confirmed that self-extrication with no collar produced a mean cervical movement of 13.33°±2.67° (range 8.25°–18.79°). The next smallest mean cervical spine movement during other techniques of extrication was found when using the LSB in-line extrication (through rear window) with a mean of 13.56°±2.34° (range 9.40°–17.25°). The largest mean cervical spine movement occurred when using the LSB and extrication of the patient through the driver's door—mean of 18.84°±3.46° (range 13.25°–26.89°).

Two techniques (LSB and extrication through driver's door, and SEJ) produced significantly higher movement than other techniques (p<0.05).

Both height (p=0.003) and mass/weight (p=0.02) were found to be significant independent predictors of movement.

Limitations of the study include the small number of participants, the narrow age range of participants, and the use of healthy volunteers. It is not possible to assess whether the findings from these simulations are transferable to the clinical setting but, nonetheless, this study provides a strong foundation on which to develop future larger scale research.

In conclusion, in simulation, haemodynamically stable participants experienced less movement of the cervical spine through controlled, instruction-led self-extrication, rather than being exposed to extrication using traditional EMS equipment. The authors argue that these findings add to increasing evidence that current practices of extrication may not provide optimal care for patients involved in road traffic collisions.

Spotlight on Research is edited by Julia Williams, principal lecturer, paramedic science, University of Hertfordshire, Hatfield, Hertfordshire, UK. To find out how you can contribute to future issues, please email her at j.williams@herts.ac.uk

So you want a career in research?

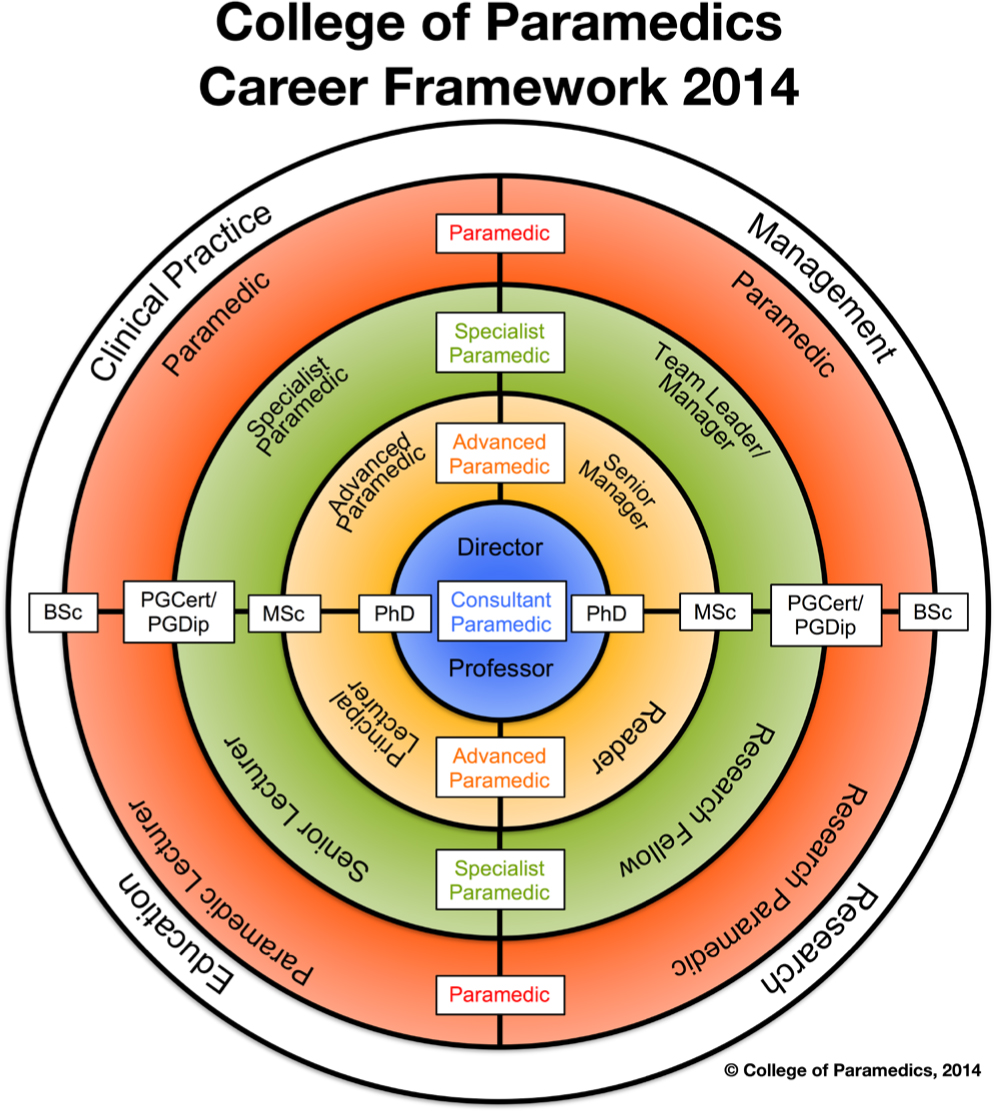

There are a growing number of opportunities for paramedics to work in clinical research. So how do you find out more about this career pathway which has been recognised by the College of Paramedics (CoP) in their Post Registration—Paramedic Career Framework (CoP, 2015)?

For the first time there is a recognised career trajectory for paramedic researchers moving from research paramedic through research fellow, reader and on to professor. If this is a route that appeals to you then you need to start making long-term plans and have a strategy in place to support your development and achieve your goal.

The advice in the CoP's publication (2015: 28) is a good start and, as suggested, you certainly should look at the integrated clinical academic programmes of study offered by Health Education England and the National Institute for Health Research—but these are not the only routes forward.

Use all available resources and never underestimate the usefulness of informal discussions with your peers, who may have already started along the research career pathway. I am sure they will give you plenty of hints and point you in the right direction. Additionally, consider using the following resources:

This is not a comprehensive list but rather offers you a few suggestions to get you started. Research is a vital and essential component that should be integral to all healthcare provision, and the opportunities for paramedics are only just starting to emerge in this area of clinical practice

Feel free to contact me for further advice at julia.williams@collegeofparamedics.co.uk