Time to get serious about ‘transforming ambulance services’ and really taking health care to patients

The second challenge has been recognised for some time and was the subject of a detailed study Life in the Fast Lane, published by the Audit Commission in 1998 (Audit Commission, 1998) and considered again in 2011 in the National Audit Offce's report Transforming Ambulance Services I (NAO, 2011). Both reports skirted the issues of what real transformation in terms of the concept of operation might look like, but they did make useful observations and suggestions. In some respects these findings paralleled an earlier American Ambulance Report authored by the legendary Jack Stout who set out the primary goals that all emergency ambulance services should strive for; response time reliability, clinical sophistication, customer satisfaction and economic efficiency (Stout, 1983; 2004).

These principles would fall into what are often termed ‘lean’ management methods and derived from quality management theory (Ryan, 2002). Stout also provided a useful metric, ‘termed unit hour utilisation’, to determine the productivity of an ambulance service by simply dividing the number of patients transported, or patient contacts, by the availability of ambulance time expressed in hours (Stout, 1983). For example, an ambulance service producing four unit hours of ambulance time and moving one patient would be operating at a 0.25 level of utilisation/productivity. This simple system has yet to be widely adopted in the UK, although discussion regarding a standardised approach is now underway. However, a continuing quest for higher productivity and stronger response time performance will no longer be sufficient as the following points will illustrate.

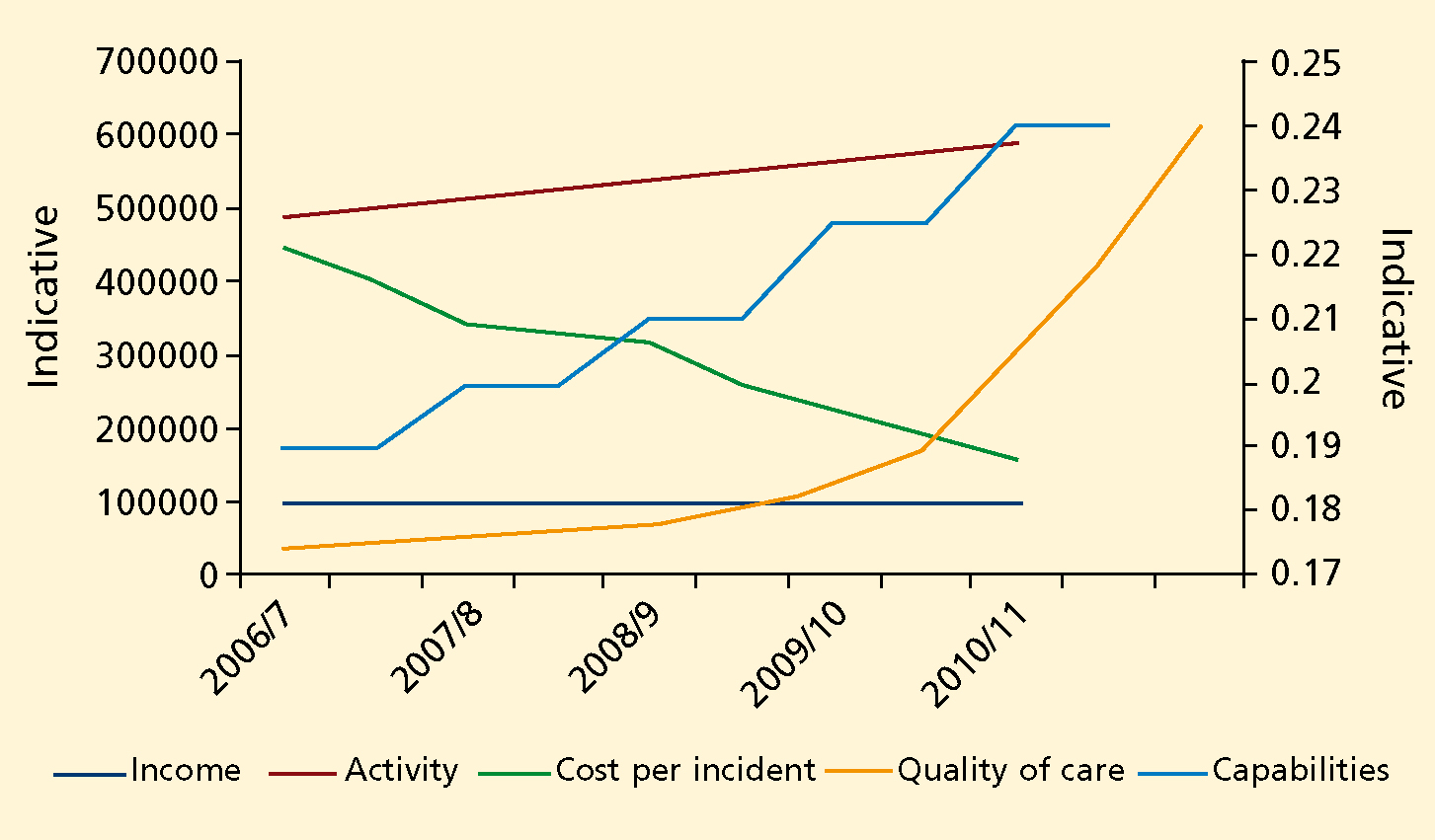

The diagram below (Figure 1) brings together the external forces and some counter-measures with the red line showing rising demand and the lower blue line refecting falling income. Bringing down the unit cost is therefore imperative through enhanced utilisation, (or improved productivity), shown in green. To address the current pressures caused by increasing low-acuity demand, the key strategic priority should be to recoup and reinvest a proportion of the funds derived from enhanced utilisation to develop new clinical capabilities, (income), while ensuring that conventional indicators of quality (activity), such as response time performance, patient safety, clinical governance and patient experience continually improve as well.

In this context improved capabilities revolve around developing specialist paramedic practice to address patient needs in both primary and critical care as the primary means of making the system generate the productivity gains. Delivery of primary care would include the assessment and treatment of a wide range of clinical presentations such as wound management, near patient testing and a wide range of referral options. Critical Care would include patient assessment, the provision of a broader range of therapeutics, advanced airway management, cardiovascular support, and the introduction of new technologies such as ultrasound, to help guide treatment in the field, ideally with the provision of on-line support from more senior paramedics and medical staff where necessary.

The conundrum for the ambulance services and the paramedic profession is how to continue to add value and improve quality in a financially constrained environment. Some might be tempted to reduce (or at least not to improve) clinical quality, or to settle for more traditional transport oriented concepts of operation. This approach fails to grasp the opportunities associated with the use of more highly qualified paramedics and specialist paramedic practice, which would unlock the prospect of delivering mobile health care and adopting a gate-keeping function. Such approaches are predicated on the basis that unnecessary transportation to hospital can have adverse financial consequences for the rest of the health economy and only works if the issue is considered at the ‘whole healthcare system’ level, rather than considering the ambulance service to be one of many silos.

If the choice is to continue with the predominant transport model, it is likely that private ambulance providers will be able to accomplish this more cheaply than many existing NHS ambulance services, but at the expense of transmitting larger numbers of patients into overburdened emergency departments. An opportunity to develop an integrated, system-wide approach could be lost resulting in increased cost and clinical risk as large numbers of patients are unnecessarily taken to hospital, ramping up downstream costs.

Clinical care came under the microscope in 2000, with an Ambulance Service Association sponsored paper outlining (Nicholl et al, 2000). This may have helped influence the 2001 Department of Health's glimmering of interest in widening the ambulance service's role in reforming emergency care (DH, 2001), spawning a veritable industry of regrettably seemingly alltoo-forgettable ‘reforming’ publications. These went largely unchallenged from the ambulance sector, but for the occasional cautionary note from commentators, including Judge, who questioned the scale and wisdom of the proposed changes in respect of the ambulance service (Judge, 2004). By 2005, Peter Bradley's Taking Health Care to the Patient (THCTTP) condensed these policy ideas and other initiatives into a document focused specifically on the ambulance service role. The report made the correct diagnosis but the implementation of the necessary changes was arguably poorly executed. The second report, (THCTTP2), was the closest the NHS ambulance services have had to current policy, but while some of the recommendations have seen some action, the failure to build them into the NHS operating framework and the lack of clear doctrine has attenuated the report's effect.

Education is the key enabler, both at the pre-and post-registration level

The move from training to education for paramedics is one example of the failure to reform ambulance services to meet the changing nature of demand. Education of the workforce is a prerequisite for lasting change and the core enabler for changing clinical behaviour, though it has proved to be slower than some might have expected. This is despite further adverse media attention from BBC's Panorama (BBC, 2000) and other programmes that have highlighted deficiencies in ambulance services’ operations and academic recognition that conventional ambulance paramedic training does not match the demand actually dealt with by paramedics (Lendraum et al, 2000).

Disappointingly, as Armitage notes (Armitage, 2012), the process of professionalising paramedic education and training is far from complete, despite the efforts of many paramedics themselves and the efforts of the College of Paramedics, whose ‘prime directive’ is to develop the paramedic profession and raise the profile of the work paramedics. The role of a strong professional body for paramedics is indeed a key ingredient to success. The College of Paramedics is the primary advocate for paramedics and in a real sense the guardian of the uniqueness of paramedic practice. The value of a sound Professional Body has not been lost on other professions and interestingly Peter Neyroud, the former chief of the National Police Improvement Agency has argued for the creation of such a body for police officers, in a report requested by the Home Secretary. Many of his recommendations for the Police, particularly in respect of the College's leadership role and its' work in relation to education and developing the paramedic profession are routine activities for the College.

Even the commitment to move to a universal minimum of a foundation degree for new entrants to the paramedic profession has yet to be implemented, although is now scheduled to happen in 2013, subject to Health Professions Council approval. Quite why the recommendations of the former Ambulance Service Association and Joint Royal Colleges Ambulance Liaison Committee JRCALC, 2000), chaired by Professor Chamberlain, which recommended embracing an educational approach in 2000 were not followed is, uncertain, but represents another example of an opportunity lost or at least not seized in a timely manner. Widespread differences in education funding remain around the country, with an almost unfathomable and unjustifiable range of qualifications, together with inconsistencies in respect to commissioning and access to the NHS bursary scheme.

This position stands in marked contrast to the situation with all other allied health professions (AHPs) despite positive research findings (Woolard, 2006; Mason et al, 2007) and publications (DH, 2003; 2008) both of which identified the potential of paramedics. Despite this attention, less than 1,000 operational paramedics have received the additional education, training and skills needed to function at the specialist paramedic level, with only a fraction of these accredited via the formal examination, designed and developed by the profession with support and quality assurance from colleagues at the Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP), the College of Paramedics and St George's Hospital, University of London.

Confusion over title, career structure, education and credentialing are now being resolved, however, most ambulance services do not yet have sufficient adequately prepared staff who can effect the necessary change to meet the diverse needs of patients. Nor does a coherent doctrine to drive the necessary philosophical and organisational change in thinking, without which meaning service redesign cannot take place. It seems that the old unconscious dogma continues to hold sway and acts as an invisible, hindering factor.

The ambulance services and the paramedic profession can make a significant contribution in providing a more appropriate service to meet the population's demand. But they can only achieve this through the development of the workforce, which will increasingly become based on the development of paramedics. Paramedics have been subject to regulation since 2000 and are an example of a ‘disruptive technology (Cheristensen, 2009). Essentially, this means that paramedics, like other AHPs, and in common with some well known technological developments, such as the digital camera or mobile phone, become more effective, more able and yet relatively cheaper than available alternatives over time. Well-trained flexible paramedics are, therefore, both a ‘game changer’ and a bargain for any health economy and a key ingredient of any efforts to produce high quality mobile health care.

Somewhat paradoxically, the establishment of a new medical sub-speciality in pre-hospital care to address the relatively small number of patients presenting with major injuries seems surprising and options appraisals detailing what advantage such services may bring are awaited. It may yet be possible to determine an economic arrangement that fuses the roles of paramedics and medical staff from this new sub-specialty and the effect on those physicians who give of their own time to provide this role, many of whom will be holding the purse strings in the new Clinical Commissioning Groups, is equally uncertain. Perhaps charitably funded Helicopter Emergency Medical Services, being a potential model, but as Rawlins notes ‘innovation [if] cost ineffective cannot—so far as the NHS is concerned—be innovation.’ (Rawlins, 2012)

This lack of consensus has been noted in 2009 by Mackenzie (Mackenzie, 2009) asking how to serve the small number of critically ill patients through the most effective combination of paramedics and doctors. Discussions continue as to how a relevant, cost effective and harmonious set of arrangement might best be achieved. Equally, The opportunities associated with the wider use of paramedics, who are already in funded positions operating as a ‘disruptive’ technology have undoubtedly yet to be fully exploited and it will be essential to complete the professionalising process, matching the educational standards of other AHPs, implementing the AHP career structure and fully embracing specialist practice in order to deploy the full benefits.

Conclusion

The steps and considerations identified above, especially when combined with the necessary organisational development, will ensure that ambulance services will be able to deliver an increasing range of services across a wider spectrum of patient need. Including advanced ‘hear and treat’ triage services to patients, using specialist paramedic control room paramedics. More ‘see and treat’ services, by deploying specialist paramedic practitioners, who have passed the pioneering Paramedic Practitioner examination, quality assured by colleagues from the RCGP/College of Paramedics examination and more critical care paramedics providing enhanced care teams targeted at the most acutely ill and injured end of the patient acuity spectrum, as recommended in the NHS Confederations review (Jashapara, 2011). But none of these capabilities can be put to best effect without a change in philosophy and concept of operation, slicker implementation and a sharper emphasis upon paramedic education and development.

In health care only two things really matter, the outcome for patients and the cost at which these outcomes are achieved (Barker, 2010). For the ambulance sector, paramedics and the taxpayer, the world has changed and the need to deliver health care in lower cost centres is now well established, but not yet routinely refected in ambulance services or in urgent or non-urgent pre-hospital care in general. The question as to which of the two alternative models, either relatively straightforward transport based, or one with a focus on clinical assessment and decision-making, provides the best value and the most positive impact for patients is clear. But the price of achieving greater workforce productivity is an unwavering commitment to offering paramedics the same educational opportunities as other AHPs, together with a need for joined up leadership between Policy makers, system leaders and the College of Paramedics.

As to whether there is an appetite to implement the new doctrine and a new concept of operation, or provide the educational opportunities in the ambulance services and amongst commissioners and service leaders is however somewhat less certain. The answer to this question will decide how relevant, flexible and adaptive both the ambulance services and the paramedic profession become in regard to the needs of patients and the public purse in the 21st century.