Paramedic practice mentors are pivotal to the success of an educational curriculum where 50% of learning takes place ‘in practice’ predominantly with the emergency service hub of any given ambulance trust. In 2006, the paramedic profession across the UK was experiencing significant changes in terms of educational curriculum, care delivery approaches and structures in order to meet the changing needs of patients as well as future corporate care delivery strategies. Those strategies were introduced to help prepare the profession for a move to higher education institutions (HEI) suggested by Bradley (2005).

Before 2006, numerous structures, relative to service delivery management, education, and clinical leadership, existed and the pace of change meant that paramedics acting as work-based trainers, supervisors or assessors had little time to adjust to new approaches. Nonetheless, a recent audit report and formal student feedback demonstrates that despite these challenges, paramedics acting as mentors have generally been providing constructive support and learning experiences which compare well with other healthcare professionals:

Paramedics acting as mentors have generally been providing constructive support and learning experiences which compare well with other healthcare professionals.

The evolution of paramedic education in the UK began in earnest in 2007, gaining full support and approval in 2011 when all paramedic education was moved in to the higher education arena.

With this move came the inevitable and gradual withdrawal of the traditional training approach to a professional structure involving peer reviews and the use of universities and academic qualifications (Jones et al, 2010). They were awarded contracts and funding by local health authorities to deliver paramedic education. Many programmes used the guidance offered by the College of Paramedics (formerly the British Paramedic Association) and all were validated and approved by the Health Professions Council (HPC) if they met their ‘standards of education and training’. Further to this, on completion of the programmes, students could apply for professional registration as the HPC (2008) were assured that they met specific ‘standards of profciency’ based on the programme's content.

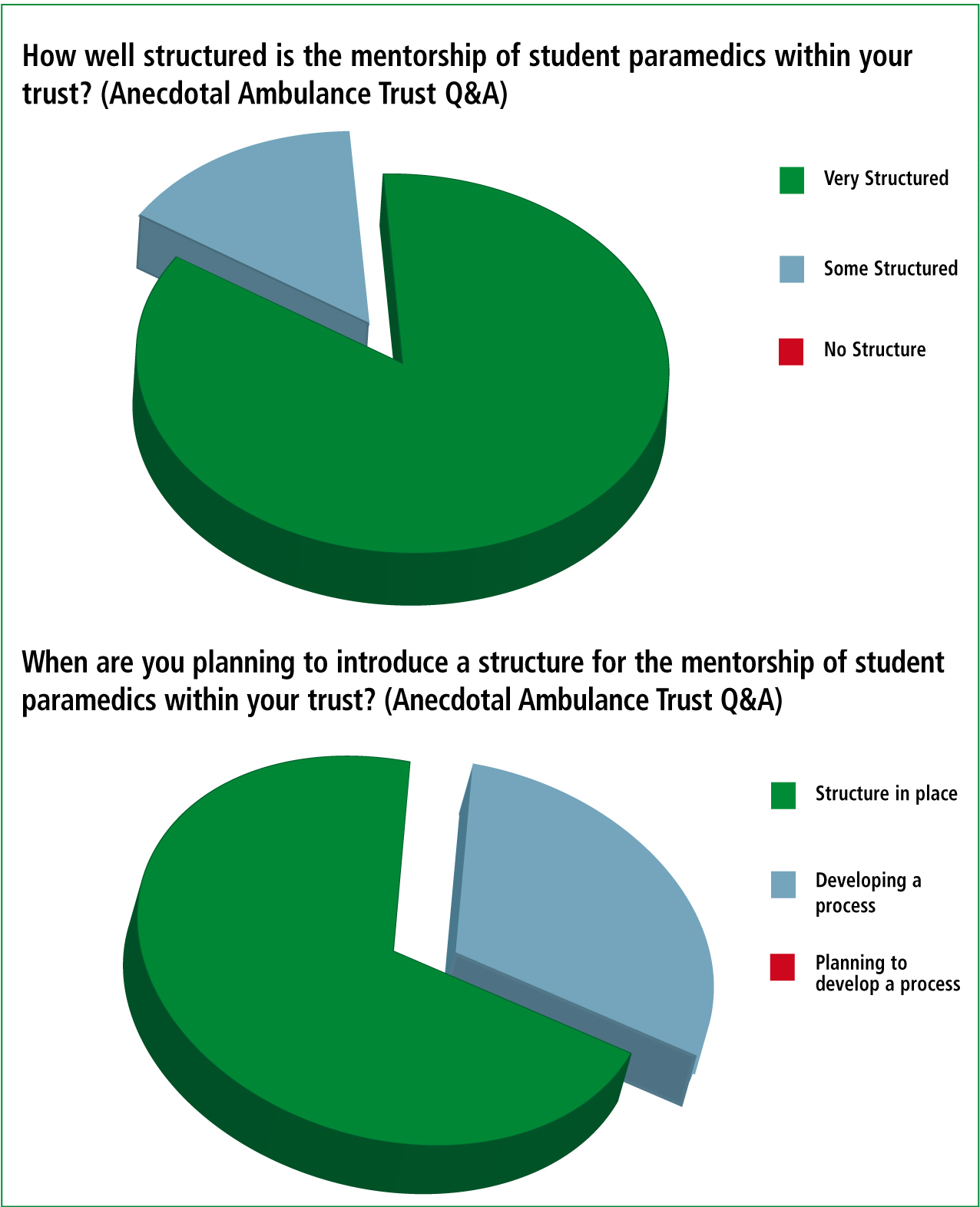

Paramedic practice has historically been measured by what is expected or what is done for patients around specific performance criteria. However, as O'Meara (2011) discusses, professionalism is more than this and intrinsic influences are important in informing how individuals have a sense of being and frame themselves professionally. This conversely impacts on the student experience in the real world environment and influences the mentees’ perception of the picture set within the paramedic identity frame. The concept of mentoring in pre-hospital practice is relatively new and, predominantly, currently encouraged in the UK by the HPC who regulate and monitor paramedics, amongst other allied healthcare professionals. The art and science of it is in its infancy in comparison to other health professions though and as a result no nationally agreed framework exists. Instead, many trusts work in many ways with pockets of good practice being engaged in sporadically across the UK (Figure 1).

Paramedic mentorship: relationships

The importance of the mentor-student relationship is generally acknowledged, however the significance of organisational influence over professional identity should not be understated. It remains a significant influence on paramedics of particular generation and one should not underestimate the often tacit standing that is placed on ambulance services in relation to acknowledgement and support for efforts and contribution made to learning in practice. First, when discussing values attributed to health, education has to appreciate generational core values and not simply expect professional values to be congruent. If paramedic practice is to continue to progress and change creating an enhanced sense of identity then firstly, there has to be dialogue with paramedic mentors. This facilitates recognition and acknowledgment of influences (historical and contemporary) that impact on values and opinions. Second, a variety of recognised and approved strategies need to be formed in order to nurture what are perceived as effective and/or appropriate values while accepting difference as a positive:

When discussing values attributed to health, education has to appreciate generational core values and not simply expect professional values to be congruent.

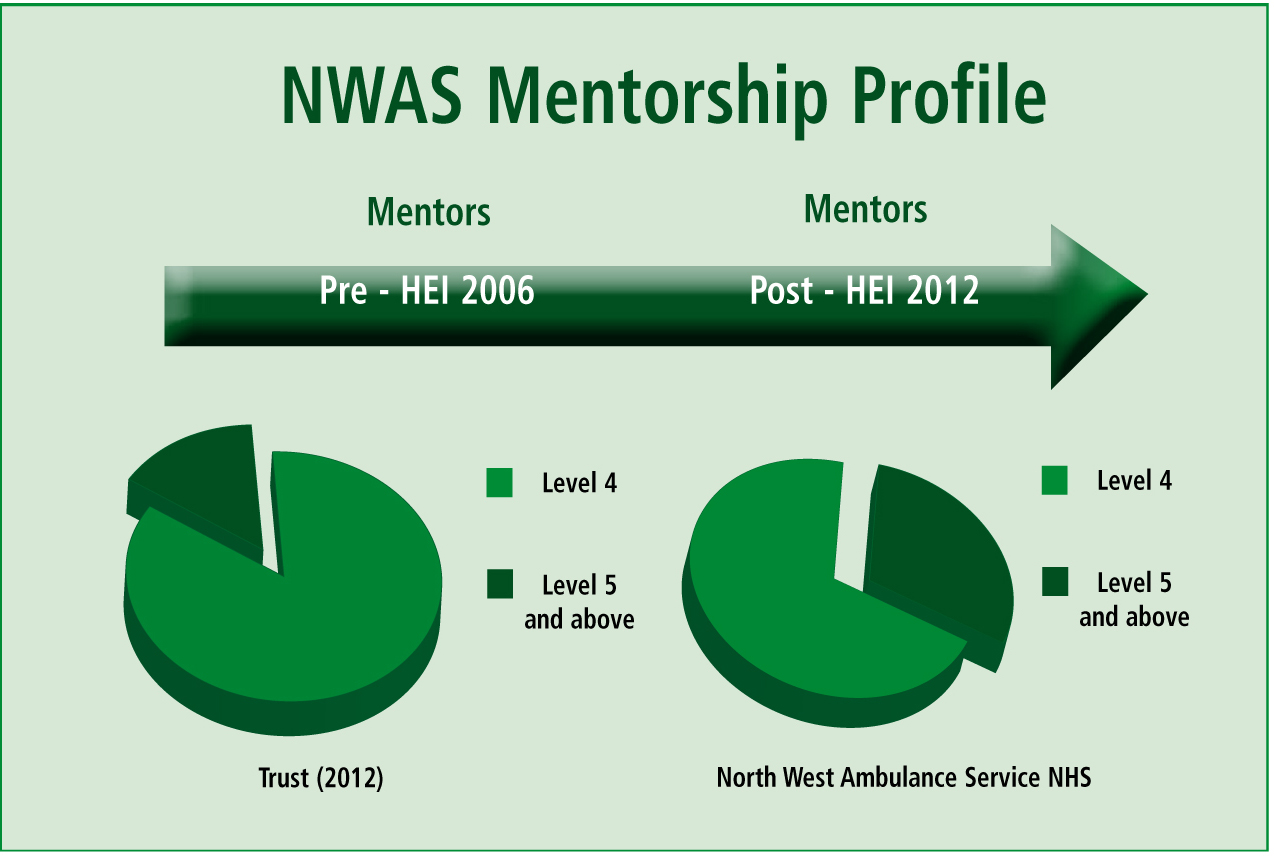

It is important for mentors to have confidence in their influence on the mentee's route to professionalism. For this to be the case, they need the education, support and resources to do the job that is asked of them. However, still no agreed level of education and support exists, some HEIs have mentorship as a core academic module but others don't. The authors believe that paramedic mentors (Figure 2) have made major impacts on this process by enrolling themselves on these modules, looking to PEFs for advice and using opportunities to allow student development. However, it is also accepted that organisational and professional acknowledgement of the mentors' role and successes needs further exploration.

Paramedic mentorship: where are we?

There is a current paucity of studies in the UK about the profession, by the profession, and this disappoints the authors. There is a need to further develop wider academic skills so that organisations can mentor the mentors. In order to achieve this, a structured network and strong communication links are needed to allow systematic preparation for all. This encourages peer support to avoid mentors feeling ‘bogged down’ with the worries of their mentees, and the responsibilities placed on them by organisations.

There is need to further facilitate on-going opportunity to update mentorship knowledge and skills annually and while it is recognised that this does not fulfil the wider needs in all aspects, it does start the ball rolling. As White and Ousey (2011) highlight there are effective multi-professional update tools available but the authors suggest that more than this needed. It remains too ungoverned, unmonitored and flexible.

The NHS in the UK, and the regulatory bodies such as the HPC, Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) and General Social Care Council (GSCC) are currently strong advocates of mentorship and this can be demonstrated by the use of simple literature searching (Table 1).

| Profession | Regulatory body | Formal mentorship stucture in place? | Mentorship structured by the regulatory body |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paramedic | HPC | No | No |

| Nurse | NMC | Yes | Yes |

| Midwife | NMC | Yes | Yes |

| oDP | HPC | Yes | Yes |

| Arts therapists | HPC | No | No |

| Biomedical scientists | HPC | No | No |

| Chiropodists | HPC | No | No |

| Dietitians | HPC | No | No |

| Podiatrists | HPC | No | No |

| radiographers | HPC | Yes | No |

| Physiotherapist | HPC | Yes | No |

| Speech and language therapists | HPC | No | No |

| Orthoptists | HPC | No | No |

| Dentistry | GDC | Yes | Yes |

The authors performed a search and found thousands of pertinent examples of articles with named professions such as nurse, social worker and midwife but apply this search process to the ambulance service using keywords such as paramedic, emergency medical technician or ambulance care assistant and the results show a very different picture (Table 2).

| Key word | Variables | Hits | Relevent |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mentor | Paramedic | 3 | 0 |

| Mentor | Emergency medical technician | 23 | 0 |

| Mentor | Ambulance care assistant | 0 | 0 |

| Mentor | EMT | 0 | 0 |

| Mentor | Nurse | 252 | 0 |

| Mentor | Midwife | 14 | 9 |

There is more to pre-hospital mentorship than has previously been discussed openly though, for example Edwards (2011) has identified the need to look beyond the student to the newly qualified registrant during a period of preceptorship. There is also a demand for graduates to have their skills of mentoring developed as they pass through their own education in order that the current raft of successful and able mentors do not dry up through natural wastage such as retirement or promotion (Williams, 2010):

The need to look beyond the student to the newly qualified registrant during a period of preceptorship.

It is well documented that change can be more effective if one is able to change factors such as technology knowledge, the physical environment, organisational structures and the people involved. The first three can be relatively quantifiable, however, as LeDuc and Kotzer (2009) point out changing values and attitudes is not so certain and can differ across generations.

Initially, among the changes, there was little or no development of the mentor network locally. Moving away from the traditional work based assessor methodology to what is now seen as a vital component in not only the development, assessment and ultimate registration of paramedic students but also as the facilitation of continuous professional development of many pre-hospital clinicians at all levels. Development has increased significantly since those early days through a combination of financial investment on the part of the employers, academic development on the part of the HEIs and physical/time commitment on the part of the many practitioners who studied the subject. This development was supported and embraced by the ambulance trust and HEI as an innovative and positive staff progression route.

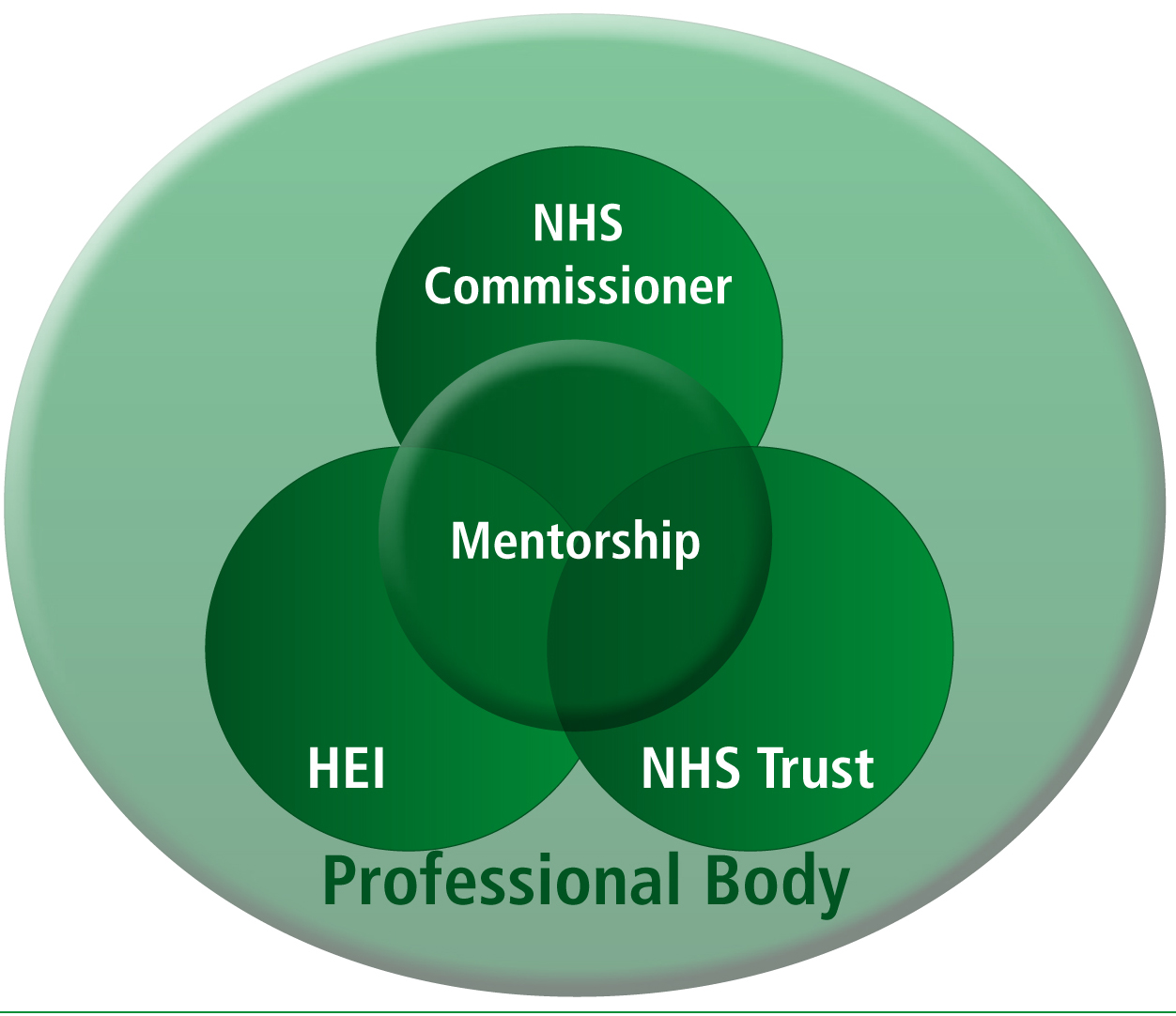

Guidance was sought from the HPC and the College of Paramedics regarding the role of the mentor, but with limited suggestion it became a process of negotiation between the ambulance service and the university to define the role of the mentor and to decide how that definition fitted in to the ambulance service structure? This enabled a profession led response to mentorship involving all parties in developing a mentor ‘ft for purpose’, and defined, locally, as ‘Mentorship in Action’ (Figure 3).

This allowed the development of a bespoke model which fitted local needs and embraced all aspects of mentorship in the development of ambulance staff and students at all levels. This model worked equally for existing staff converting legacy qualifications and for those applying for university places via UCAS. The development of a model was supported, if not embraced, by the ambulance trust and the university as an extremely innovative and positive staff progression route.

Part of the evolution was the employment of PEFs within the trust. A new role within the organisation but not within healthcare education, it was an initiative launched in Scotland and rapidly rolled out due to its success in enabling students to be allowed the opportunity to achieve competencies in practice through the use of ongoing achievement records or practice achievement records and documents with the full support if mentors within the organisation.

But it was found that this emerging role brought with it other responsibilities:

It is widely reported that a collaborative approach and educational route supported by a Strategic Health Authority (SHA) is successful and local successes are being monitored with interest by other UK ambulance trusts.

Paramedic mentorship: the future

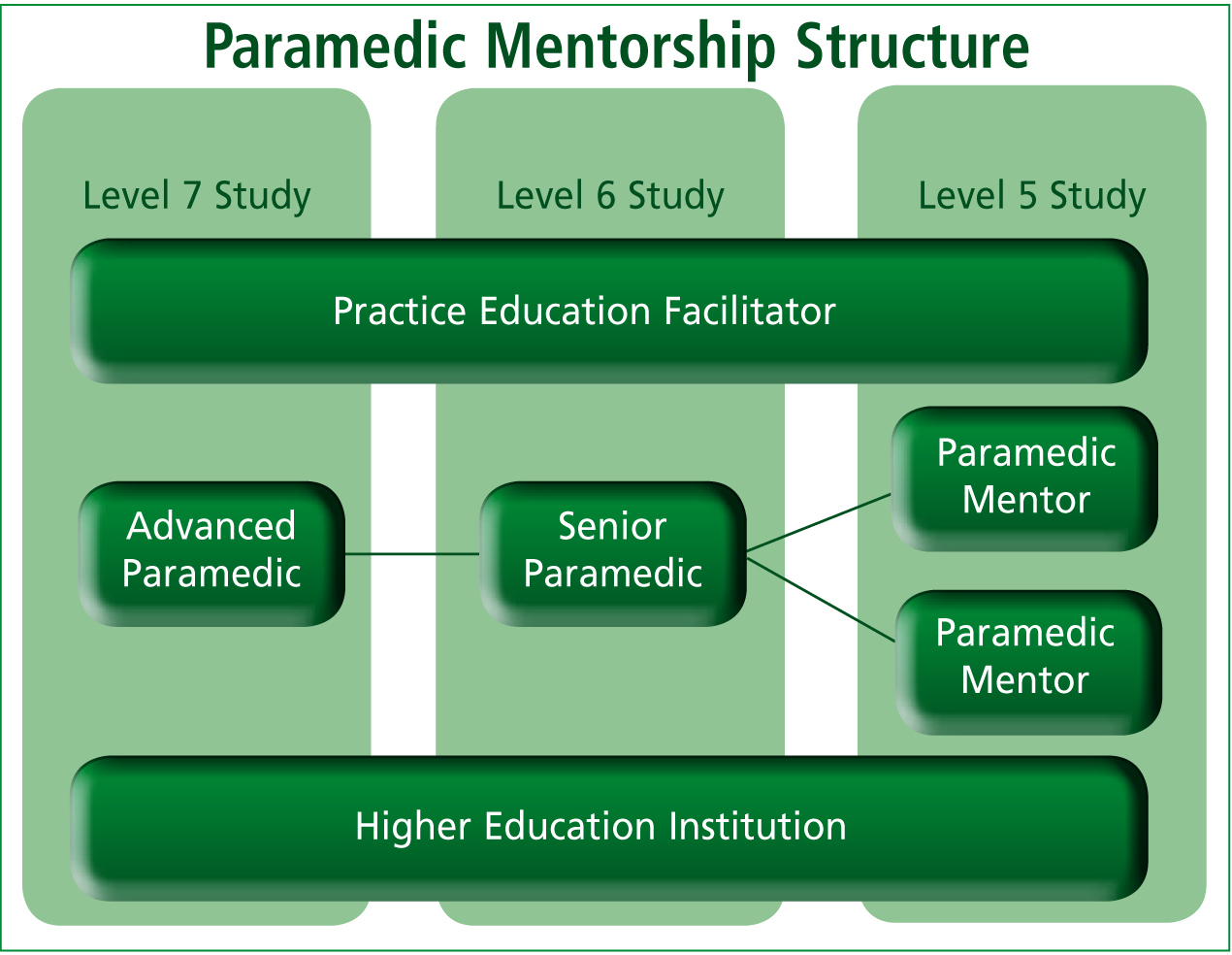

The authors would like to go further now and explore the viability of introducing national, structured, fit-for-purpose mentorship to the ambulance service in order to bridge demographic gaps (Figure 4). Authors have written about pre-hospital mentorship but few have truly studied it. It has been seen as a vital tool in the development of clinical skill use in practice for a number of years (Best et al, 2008) and even as ‘essential’ if those learning the components of the profession are to gain mastery of its intricacies. There is international recognition that the use of a mentorship model does have the advantage of streamlining a student's transition from student to registrant in a sympathetic, structured, accountable and effective way (Pointon and Williams, 2008).

That smooth transition and relationship between education and practice offers further opportunity for what Bigham et al (2010) termed ‘paramedic-driven research’. So what can be done to espouse the benefits of mentorship within the ambulance service in order to increase skills of mentors and their unrecognised counterparts while simultaneously ensuring that those being developed are adequately prepared for their role? There have been calls for mentorship to be a more inter-professional activity (Clemow, 2006), this is seen to offer the opportunity of excellence in clinical placement learning and subsequently more assurance of students’ fitness to practice autonomously. The role of the interprofessional mentor is discussed by Marshall and Gordon (2010), they describe a study of health and social care students focussing on three core components—interprofessional learning, professional supervision and assessment of competency:

Those smooth transitions and relationships between education and practice ofer further opportunity for ‘paramedic-driven research.

While many educators within HEI are turning towards media enhanced learning (multi-fidelity simulations, work-based learning, online technology, problem based learning) to enhance the student experience, there is little evidence to support any single one of these as an effective pedagogy in paramedic practical education (Pointon et al, 2009). This is where a strong, positive mentorship system, working hand-in-hand with these methods is of true benefit to the student and ultimately the profession.

To augment the educational, structural, leadership and processes that influence the development of a support network for mentors, someone needs to consider when it is right to adopt a more progressive approach to mentorship structure. PEFs are in an ideal position to bridge any perceived educational-practice gap and introduction of structure and the authors suggest that they continue to play an integral part in national planning and development.

From a profession-led point of view, the authors suggest that the limited structured guidance from the HPC makes driving placement strategies forward more challenging. Interestingly, the HPC does not mention the phrase mentor in the Standards of Performance, Conduct and Ethics (2008) nor what specific qualities/qualifications are required but do suggest that the registrant must ‘share their knowledge and expertise with other practitioners’.

Paramedic mentorship: the way forward

Pride in leadership, support and guidance needs to be embedded in all pre-hospital clinicians. All paramedics should act as mentors but organisations need nationally approved process and structure to accommodate this requirement.

It is important, however, that those leading a national process avoid over structuring mentorship out of mainstream practice. Avoid it becoming too hierarchical: treat it as a key step in the development of all pre-hospital clinicians. A stronger, professionally led approach is needed to augment organisational strategies and structures, better enabling the mentor, promoting identity within the profession rather than just the local trust.

It would be too easy to rest on laurels and to look at the progress that has been made so far on a local basis in the development of a mentorship model. ‘the goal of education, if we are to survive, is the facilitation of change of learning’ (Rogers, 1969), the profession continues to undergo massive change in a way that recognises professional status and we must continue to adapt but not just locally.

At a local level this has been recognised through the introduction of a new clinical leadership strategy in line with the College of Paramedics (2008) Curriculum Guidance and due to the increasing priority in supporting, mentoring and challenging clinical practice (Association of Ambulance Chief Executives, 2011), this ensures that, with the introduction of Advanced Paramedics and Senior Paramedics, a robust clinical support structure is provided to all clinicians, in all aspects of professional practice. So why not structure this nationally? It is the authors’ opinion that the ambulance service and the paramedic profession does not lose track of the importance of mentorship and preceptorship.

We need to avoid Ponick et al's (2003) vision of bringing well-educated optimistic novices into the ranks only to let them crash and burn in a few months and would argue that rather than concentrating on the higher echelons of the more clinically qualified clinicians, it must also take a step back to look at the perceptions and aspirations of potential paramedics in developing a programme that continues to provide paramedics who are ft to practice.

The authors suggest that there is certainly ‘food for thought’ in providing further research in to the national development of mentorship and supporting learners in practice, and feel that this culture change regards education should be explored at a later stage when the opinions of those first graduates can be explored after starting their journey of moving from novice to expert (Benner, 1984).

It is important for individual paramedics to have confidence that they directly influence the route to professionalism and have the education, support and tools to do the job. The authors, of this article believe that paramedics acting as mentors have a major impact on this process which needs recognition nationally and governance by an organisation with the strengths, links and weight to have a positive influence. However, they accept that knowing how important both organisational and professional acknowledgement of the role is to this group needs further exploration.

Conversely, what are the potential consequences of failing to recognise the importance of all party participation to structurally collaborate in the process of mentorship? We daren't think...