Simulation is a key learning strategy embedded in Australian paramedicine curricula (Barr et al, 2014; Boyle et al, 2007). A driving factor is that simulation is a learner–centred approach that provides students with the opportunity to apply their knowledge and skills to a real world problem based learning cases encouraging students to construct their own connections from authentic activities within a dynamic learning and teaching environment (Biggs and Tang, 2009; Tupper et al, 2013). The paramedicine program at the University of the Sunshine Coast (USC) uses simulation to underpin the curriculum design, which allows the student to engage with clinical presentations and link their learning environment with the real world. In this paper, pedagogy is considered to be the method and practice of learning and teaching activities that guide the development of future paramedics (Shulman, 2005; Biggs and Tang, 2009).

The USC paramedic program has developed a series of contextualised simulations using immersive media (IM) intended to enhance links to authentic practice and improve student engagement. The development of the new learning strategy was based on experiential learning theories, however there was a paucity of definitive research for using immersive media due to the recency of this innovation. The simulations using IM were situated within an intensive educational session prior to a clinical placement to assist second year students to make connections between previously taught concepts (Bland et al, 2001). At USC, the IM strategy was used in combination with low to high fidelity simulation techniques, tools and strategies. It incorporated the use of the immerse studio that enabled a 270 degree projection of video of several urban environments to simulate the scene of an incident. The IM strategy was designed to facilitate a learning environment where the learner is able to be interactive with the environment and equipment in a safe learning space. According to Lateef (2010) and Clapper (2010) using IM should enable the creation of dynamic, complex and challenging situations targeted to specific learning outcomes. The intended benefit of including simulations with IM within the curriculum was to enhance the development of problem solving and clinical decision making skills. This was also supported by the use of Johns Model of Structured Reflection (Cox, 2005) to establish deeper understandings of key concepts and builds strategies to enhance future practice.

The IM strategy was first piloted at USC in 2015. The USC immersive studio is 36 square metres with an external control room that can be used by the facilitator and for peer viewing. The immersive studio has the capacity to project video to three walls providing a 270 degree continuous scene (Fig. 1 and 2). The purpose of this study was to explore student feedback of simulations using IM to improve both the efficacy and student engagement.

Methods

Simulation pilot site and structure

The IM pilot was held in the immerse studio at the University of the Sunshine Coast, Australia. Video footage was collected from a street corner in the CBD of Brisbane and Roma Street train station. The footage of each location was concurrently captured by three cameras mounted on a central platform and edited in post-production to enable projection onto three walls to create a seamless dynamic street scape (Fig. 1 and 2). The learning outcomes for the simulations were constructed using the three learning domains of psychomotor, cognitive and affective as described by Harrow (1972), Bloom (1956) and Krathwohl (2002).

The IM pilot used a standardised patient (facilitator), low and high fidelity simulation equipment and part task trainers. The participant to facilitator ratio was 8:1 and students were actively engaged in six simulated problem based learning cases throughout the day which included both trauma and medical emergencies. Problem based learning is a student centred, pedagogical approach to learning and teaching that enables the student to have an active, hands on, learning experiment through solving of a complex, contextualised problems (Boud and Feletti, 1997). These course learning outcomes were directly linked to the simulations which included pre-engagement activities that address multiple learning styles, such as problem based written tasks (visual), e-lectures (visual and auditory), video resources (Auditory), the immersive simulation (kinaesthetic) and critical debrief. Furthermore, the learning outcomes of these simulations are constructively aligned within the program of study and both the graduate competencies set by the Council of Ambulance Authorities and the University of the Sunshine Coast's graduate attributes.

Each simulation consisted of a fifteen minute session for active paramedic clinical assessment and case management, immediately followed by a thirty minute structured debrief and reflection session. During consecutive simulation sessions participants assumed multiple roles as either a responding paramedic, bystander or peer assessor. For the debriefing component the participants were asked to reflect on their own practice and or provide constructive feedback on their peers' performances against three paramedic specific skills sets: non-technical skills; technical skills performed; and timely implementation of skills.

Consensus based focus groups and emerging themes

A convenience sample of second year students of the Bachelor of Paramedic Science program at USC who undertook immersive simulation in 2015 were invited to attend a focus group that aimed to explore their feedback of the immersive simulation. The focus group took place three months after the simulation and was facilitated two paramedic academics, one of which was involved in designing the IM pilot. Prior to the focus group students were asked to consider their experiences during this simulation and to identify the benefits and limitations of the immersive simulation experience. A modified Nominal Group Technique (NGT) consensus method was used during the focus group to identify positive and negative aspects of the experience in order to inform the design of future immersive simulation.

Focus groups are a powerful strategy to collect feedback that can yield deep insights group perceptions (Punch, 2009; Stewart and Shamdasani, 2015). A strength of the NGT is the collaborative, de-identified process of reaching consensus (Delbecq et al, 1975; Jones and Hunter, 1995). As such it is an appropriate tool that harnesses the student voice to inform quality improvement processes in paramedic education. The NGT method used in this study has been previously used in paramedic education (Barr et al, 2016). It has two distinct stages of collaborative “brainstorming” as well as anonymous “judgement”. In this study ‘brainstorming’ was a twostep process in which. The first step was group feedback. In a ‘round-robin’ style each student presented one of their experiences to the group without discussion. This continued until there were no further ideas from the students. The experiences described by the participants were captured on a white board by one of the researchers and the wording vetted by the participant who voiced the experience. The second step discussion and clarification of ideas was then conducted. At this point individual experiences were discussed and refined to create a list of positive and negative themes by the focus group participants. This process was facilitated by the researchers and thereby the data could be perceived as co–constructed. Nevertheless, the researchers took steps to minimise their influence on the feedback given during the NGT process. Researchers summarised participant statements to refine the feedback in order to present back to the group for confirmation. During this phase the researchers were cognisant of remaining impartial.

The first judgement step was silent independent voting. Students received 5 votes each that could be used to weight the most important theme or themes generated in the previous ‘brainstorming’ stage. Students could allot the votes on one theme or spread them across several positive or negative themes at their discretion. The second step was rank ordering. Votes were aggregated providing a rank order of experiences from high priority to low priority.

Ethics approval was granted by the USC Human Research Ethics Committee (A/15/754).

Results

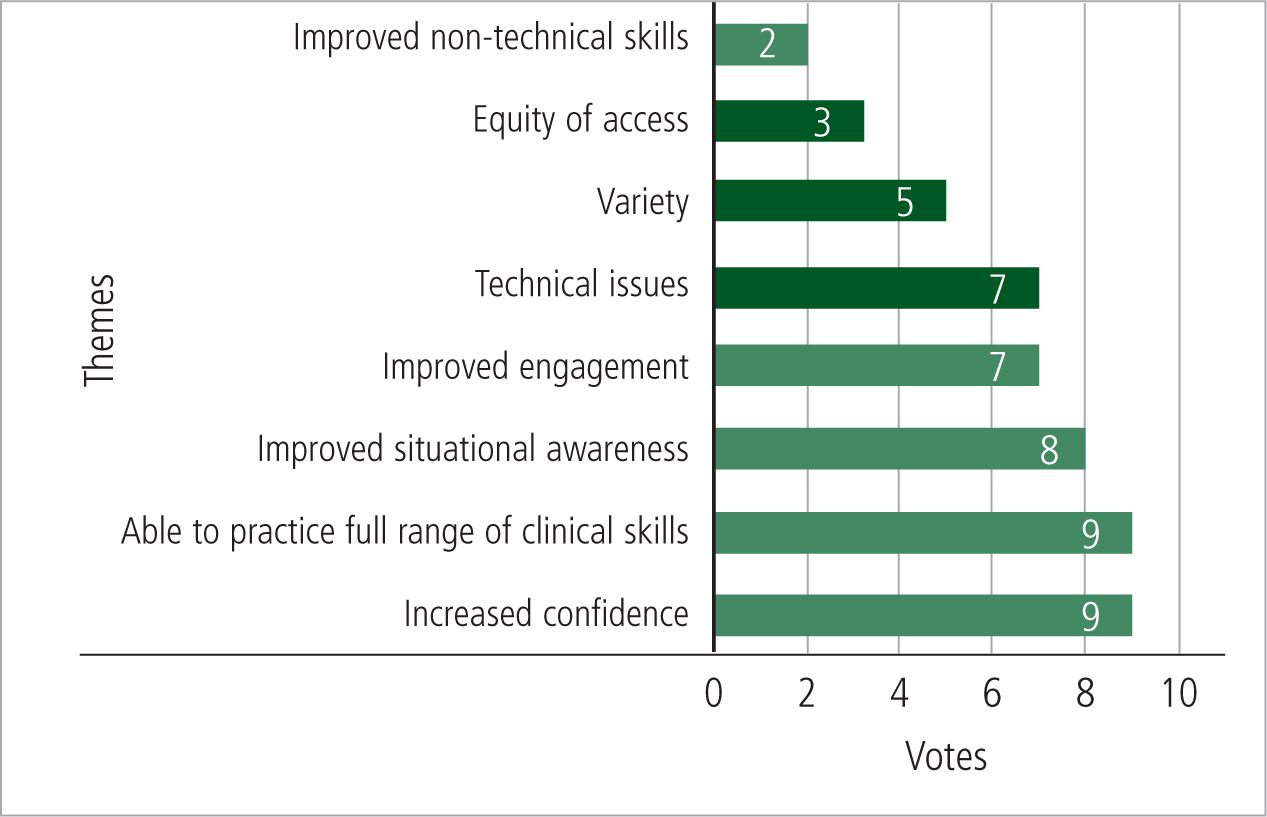

Weighted participant feedback is shown in figure 3. Two areas of consensus emerged in the focus group that indicated the value of the use of immersive media within simulations according to the participants. The first theme was the benefits derived from the closer approximation of a real world environment through 270 degree video projections. In contrast to previous simulation experiences where simulations were conducted in a normal classroom, the students felt immersive simulation led to: increased confidence within the scenario due to increased focus on the role, increased psychological comfort and a decreased perception of being judged; improved situational awareness due to the dynamic environment with real life noises; improved engagement, and improved non-technical skills of communication and leadership (Figure 3).

The second positive theme discovered was the feedback arising from the immediacy and realism of feedback by using the facilitator as the patient in comparison to using students or manikins as patients. This strategy was perceived by participants to allow them explore and demonstrate a broader range of clinical skills, including a deeper level of history taking than in other scenarios practiced within the USC programme.

Focus group participants perceived three broad areas to concentrate on regarding improvements to be made: technical issues, variety of scenes, and equity of access.

Discussion

The NGT method for the evaluation of the IM pilot allowed a structured process of critical feedback from the student participants regarding the value and limitations of the event. However, care must be taken when interpreting these weighted themes as larger themes may consist of smaller low weighted items. In this study students were positive about the structure of the simulations and perceived IM as a valuable aspect of their curriculum in contrast to previous simulation attempts on the floor of a classroom using low fidelity part task trainers. According to the results, this can be attributed to the closer approximation of a real world, authentic learning environment facilitated by the construction of the simulations and the use of 270 degree video projection.

An additional benefit was that students felt that the IM allowed the practice of a broader range of technical and non-technical skills than in previous scenarios in other courses. This finding could be due to the range of simulation modalities and techniques which included the use of a facilitator lead standardised patient.

The feedback indicated that the participants perceived simulations using IM as engaging, increased their confidence and situational awareness, and improved their non-technical skills. Students also positively perceived the increased length of scenario in which they were able to practice a full range of skills. The benefits the students have described may indicate that this method of simulation assists with transformative learning and socialisation into the paramedic role. The benefit of weighted feedback also allows important themes to emerge for improving the design of the immersive simulations. The three most important themes which will be considered to improve the IM are to: ensure technical issues did not interfere with the simulation environment; develop an increased variety of simulations; and expand access to immersive simulation.

The debriefing session added the element of Transformative learning (TL) as it involved meta-cognitive reasoning and critical reflection on the part of the student and emphasized insight into sources, structures and points of view of knowledge by judging relevance, appropriateness, and consequences. A simulation using IM which includes TL may facilitate the skills, insights, and dispositions of the student that are essential for professional practice (Cousin, 2009; Mezirow, 2003). As future professionals, paramedic students will operate in an environment where models of care will continually change as the evidence base grows. Students must have the ability to be cognitively flexible through ongoing critical reflection concerning their assumptions.

Limitations

Focus groups have a number of limitations. In this study a convenience sample of participants was used which may have affected generalisability of the results. A second major limitation of focus groups is the tendency for certain types of participants to dominate the discussion and for only socially acceptable opinion to emerge (Stewart, 2007). The NGT process should have minimised this concern as each member was given the opportunity to contribute equally to the brainstorming of ideas and anonymously weight the themes generated.

Conclusion

Student feedback gathered through the NGT consensus method supported the use of IM strategy as well as highlighted the ancillary beneficial co-learning potentials of these rich learning environments. The NGT consensus method enabled a rich and focused discussion in developing consensus on several themes that may not have been identified through individual student responses to surveys or other feedback collection methods. The findings of this study show that students perceive IM as valuable to their learning trajectory. All USC paramedic students will now have IM included into a capstone simulation based course, the design of which will be modified to create more authentic simulations and address participant concerns.