This paper was written following a critical analysis and structured reflection on mentoring and teaching a dyslexic paramedic student. The original case study and analysis was conducted for submission to the University of Brighton in fulfilment of the practice placement educator (PPEd) accreditation. The student participating is the topic of a case study to explore some of the practical issues around supporting dyslexic students on placement. This paper has been written as an account of the author's reflections on preparing for and delivering a teaching session on the use of a ParaPac.

There is a significant gap in research on the practice learning experiences and needs of clinical students with dyslexia; even more so for paramedic students. A brief review of the literature, which is largely based on nursing students, indicates three main issues: there is still a stigma related to disclosure of dyslexia (Morris and Turnbull, 2007); there are known factors that help and hinder learning (Gopee, 2015); and that teaching styles need to be varied and pragmatic (Deane and O'Neil, 2011).

In this case study and analysis, the student was taught how to use the ParaPac, a ventilator machine that assists patients' breathing. The ParaPac is, in the author's experience, largely underused. The anonymous student who volunteered for this case study has non-specific dyslexia, which includes visual/reading problems and difficulties with speech processing. The aim of the original case study and analysis was to discover what paramedic mentors can do to improve their interactions with dyslexic students. The author is also formally diagnosed as dyslexic, so has personal insight into this learning difference. The author received great support throughout her paramedic degree and still receives support as a qualified paramedic. Because of the personal and reflective nature of this case study, the author will be referred to in the first person.

Review of the literature

Dyslexia has many dimensions, and should not be represented by one simple definition (Reid, 2016). Dyslexia impacts people in many different ways, taking a range of diverse forms such as, but certainly not limited to, structural and functional brain related factors (Galaburda et al 2006); processing speed (Wolf and Bowers, 2000); and literacy achievement (Siegal and Lipka, 2000). My own definition used in this study is: ‘difficulties in processing, particularly literacy and the acquisition of reading, writing and spelling’. Other types of dyslexia are less reported, such as slightly impaired cognitive functions, slower speed of processing, difficulties in organisation or speech processing, and often problems such as performance within education.

Around 5% of the global population experience dyslexia (Rasmus, 2001). More specifically, it is thought that 15% of nursing students have dyslexia (Shellenbarger, 1993). From a literature search specific to paramedics and student paramedics, it was apparent that there is a significant lack of research into dyslexia diagnosis, disclosure and experiences. Presumably this is because the paramedic role is a recent (academic) developing profession, and the evidence base is yet to be built.

A report by Morris and Turnbull (2007) highlights the stigma with disclosing dyslexia in clinical practice. They found that a majority of nurses do not disclose dyslexia for fear of discrimination. It was also noted that there is a higher number of people diagnosed with dyslexia than ever before in higher education, yet the research on dyslexia among nursing students is limited. Morris and Turnbull's qualitative study of 18 diagnosed dyslexic student nurses, found that although each had personalised ways of coping with dyslexia in clinical practice, under half of the students had not disclosed their dyslexia to colleagues for fear of stigma. The study found that where education is offered to clinical staff about how to support dyslexia, disclosure rates increase (Morris and Turnbull, 2006). Illingworth (2005) in her study on dyslexia in clinical practice found that dyslexia affects career choice and progression, and that a dyslexia-friendly working environment helps staff achieve their maximum potential.

Videos and animations have been found to support dyslexic paramedic students (Deane and O'Neil, 2011). Perhaps with this in mind, a combination of classroom and practice education with emphasis on alternative styles of teaching, such as use of videos, e-learning, high and low fidelity simulations (Munshi F, 2015) could encourage a motivation for personal, professional and lifelong learning. This could encourage all our future paramedics to develop themselves professionally. The literature suggests that paramedics including those with dyslexia benefit from learning in a very tangible way. Gopee (2015) identified factors that promote learning and those that do not. Learning is promoted when students feel they have enough time to practise skills and have approachable staff. Interruptions, lack of time and a disorganised programme of teaching (for example, trying to teach whilst in the ambulance) hinder learning (Gopee, 2015). This is very relevant for all mentors and students but particularly for dyslexic students who may need extra time, concrete examples and a quiet environment. Dyslexia Action (2016) give examples of best practice in supporting learning, such as using bullet points; emphasising key points in bold; providing step by step instructions; checking regularly for understanding; signaling changes (‘first’, ‘second’, ‘finally’); encouraging good ways of recording; praising efforts. Gopee (2015) suggests that the role of mentor should include careful planning of practice placements to ensure that students have relevant support.

Key research questions emerging from the literature might be:

With the second question in mind I undertook a small case study.

Reflective cycle

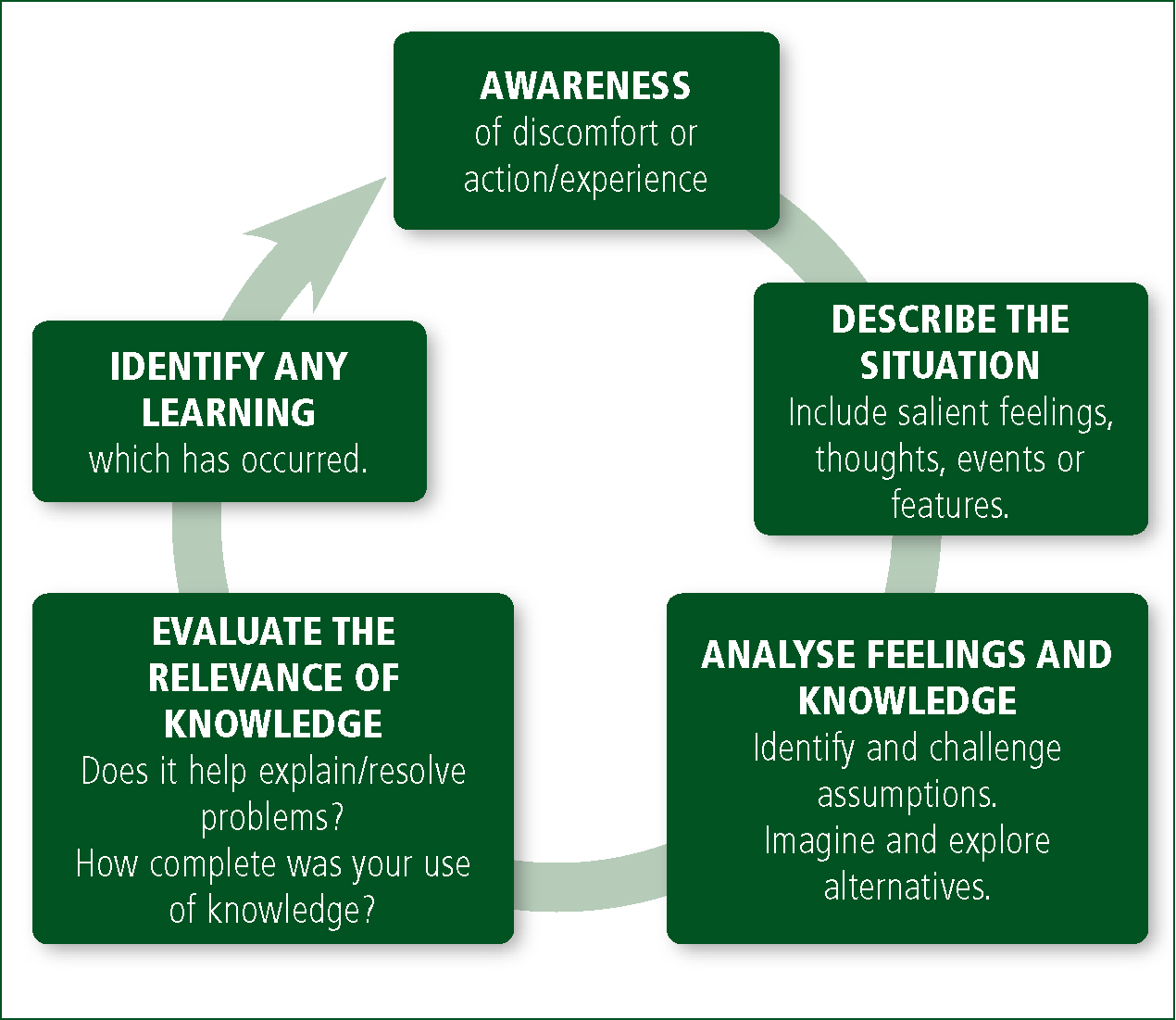

Atkins and Murphy's (1994) reflective cycle (Figure 1) was used to reflect on the experience of preparing and delivering a teaching session to a dyslexic paramedic student.

Stage 1: awareness

I was informally diagnosed with dyslexia at school and then formally tested and diagnosed with dyslexia prior to starting my degree in Paramedic Practice. I personally experienced the stigma and barriers associated with having a learning difference described by Morris and Turnbull (2006). I was therefore aware that the dyslexic student I was teaching may be feeling anxious and nervous about their performance, and that it was my duty to pay attention to making the teaching session as inclusive and accessible as possible. Equally, I had to deal with my own anxiety about my performance in delivering an effective learning session.

Stage 2: describe the situation

This case study emerged from an assessed teaching and mentoring session that I prepared and delivered with a dyslexic paramedic student. In this situation, I was being assessed by an external assessor as part requirement of the accredited supervisor's course, and the student was being assessed by me in order to achieve their practical skills towards their registration requirements. This reflection cycle (Figure 1) focuses on my learning, acquisition of knowledge and skills for teaching and mentoring (Atkins and Murphy, 1994).

In preparing the mentoring and teaching session on how to use the ‘ParaPac’, I favoured kinaesthetic methods, often preferred by those with dyslexia (Exley, 2003). This meant planning for more hands-on, tactile and practical learning, as opposed to just showing or just telling. The student was given time to touch and move the dials on the equipment, as well as practice in attaching the required tubes. The student used an endotracheal tube so that it was possible to hold it and envision a real scenario. Plan for the session included a brief verbal introduction along with a description of the skill being taught, and regular checks to make sure the student was understanding how to use the ParaPac. Before the session, I prepared teaching materials, including a hand-drawn diagram of the ParaPac with colour-coded words and pictures, so that the student could connect the auditory and kinaesthetic with the visual representation.

The student was given a piece of paper explaining the learning outcomes, aims, and feedback to expect, and assured that questions were welcome. After the explanation was complete, I asked the student to set up the ParaPac as shown. They were given as much time as needed for this process, and after it was completed I started the feedback. The feedback was given by what is referred to as a ‘feedback sandwich’ (Gopee, 2015). This means sandwiching negative observations between positive observations. I also asked the student to identify what went well, what went particularly well, what could have been improved in their performance and what they would do differently in the future.

The student was able to use the machine with some skill, but found that they needed more time to learn an adult's basic tidal volume and respiratory rate, but this is something that may come with practice.

Stage 3: analyse feelings and knowledge

The third stage of the Atkins and Murphy (1994) cycle is around ‘knowledge’. On reflection, I felt that the knowledge needed for mentoring and teaching students with dyslexia was much greater than previously anticipated. I had to predict that the student might ask more in-depth questions, to feel confident about their own understanding of the skill, the theory and mathematical explanations.

Reading the theoretical and practice-based literature on the experiences of dyslexic adult students gave me the confidence to prepare a session that was practical and focused on visual and kinaesthetic approaches (Exley, 2003).

Choosing the ParaPac as a teaching tool was a choice based on my experience: I have previously struggled with learning the ParaPac, so turning myself into the learner and understanding this equipment better helped me in knowing the best way to teach it.

Stage 4: evaluate the relevance of knowledge

The discovery that I did not understand enough about inclusive learning and the holistic nature of dyslexia, made it clear that basing my teaching on my own experience with dyslexia was not enough. ‘Inclusive learning’ approach indicates teaching that assumes that it must be accessible to all; hence, includes all learners within the teaching (Tomlinson, 1999). I narrowed down some of the key problems that student paramedics with dyslexia may experience, by using colour-coding, demystifying terminology, and understanding medical abbreviations. My next project was to explore the alternative styles of teaching and be conscious of whether I was appealing to all the senses (auditory, kinaesthetic and visual).

Previous reflection had taught me to slow the normal pace of delivery, make eye contact and give all students time and space to ask questions. Attention was paid to making a potentially stressful environment less intimidating for the student. An ambulance is not the easiest place to teach. I ensured that the university assessor was included in the seating arrangements, rather than sitting or standing behind me, which could have been intimidating for both myself and the student.

Prior to the session with the dyslexic student, I conducted a brief experiment by asking a non-diagnosed student to listen to my lesson with no visual or kinaesthetic prompts, and compared the outcome with my student, who did get the prompts. It is not a quantitative study, as comparing students can be challenging due to the diversity of learning. However, the non-prompted student found it difficult to convey back to me the information that I had taught, but the prompted dyslexic student managed this with an air of understanding and knowledge.

Teaching during a mentoring session can be a great benefit to both the teacher and student. I have found that my knowledge on learning styles and terminology has increased, as has my confidence with teaching. It was a struggle to remember the mechanisms required to run the ParaPac: as a result of teaching its use, I have greater confidence in using the ParaPac in the future.

Together with the practical teaching and the academic research, it is apparent that inclusive learning benefits all students, not just students with dyslexia. Students do not legally have to disclose a dyslexia diagnosis. Therefore, introducing inclusive learning for all students using accessible learning could benefit more students. A way of describing inclusion can be found in Table 1.

| A dropped kerb at a pedestrian crossing was initially instated for wheelchair users. However, this also benefits pushchairs, people with physical disabilities, and children. If the council had designed things so that only wheelchair users could use this dropped kerb, other people may not benefit from this convenience. This applies to accessible learning: topics prepared for the dyslexic student can benefit all students. |

Before my teaching session, my student had disclosed their dyslexia to me and to other colleagues. This made preparation easier and gave me more of an insight into how the student would benefit most. As mentioned by Morris and Turnbull (2006), if students are encouraged to disclose their dyslexia, staff/student relationships will be improved. Equally, in the case of undiagnosed dyslexia, a mentor could have a confidential open conversation with the mentee. This may make a positive difference to their education and the relationship between mentor and student. Any concerns when communicated to the university's education facilitator could also benefit the student. However, if the student is formally diagnosed with dyslexia, discloses this, but wishes no additional support, it is their decision, which should be respected. If the mentor uses an inclusive learning approach for all students, then the dyslexic student would not be made to feel they were getting additional support if they didn't want it, but would be reaping the benefits of the inclusive learning approach.

Stage 5: learning and impact on practice

This case study has looked only at a teaching scenario with a dyslexic student. As a paramedic and mentor, I have learnt to plan teaching sessions well in advance, and to consider how to embed kinaesthetic, visual and auditory elements into the teaching plan.

The learning goes beyond skills teaching into how to support the dyslexic student in everyday paramedic practice. There are implications for the paramedic practitioner and mentor: dyslexic students may need more time to mentally prepare for completing the patient assessment forms and other referral forms and paperwork. They may need to revise and practice procedures in non-emergency situations (for example veno puncture and intubation). Paramedic mentors could suggest that students regularly familiarise themselves with forms during quieter times of the shift, or practise assembling cannulation syringes and talking through different sizes of needles and appropriate and effective uses. Paramedic mentors can encourage and support students who might find that drawing, mind-mapping and colour-coding instructions is more effective in helping them to learn or remember procedures.

There may be other implications for paramedic educators and mentors. A less common factor associated with dyslexia is difficulty in verbal communication. Students may need extra time to form their words. When rushed to speak faster, they may shut down with frustration or difficulty. It is critical to give these students time whenever possible. Finally, organisation may also be something that a mentor, paramedic educator or manager may need to discuss with their student. Some individuals with dyslexia struggle to organise their calendar and shifts, and consequently may be late or turn up on the wrong day or wrong time more than expected. Some time spent planning with them may be helpful; perhaps drawing up a plan, including a system of who to contact if they were going to be late – this can reduce anxiety.

For mentors, competence as a clinician comes in moving from novice to expert in both skill and mentoring (Benner, 2001). The Nursing and Midwifery Council's (2008) guidance on mentoring supports this notion that all mentors should facilitate learning for a variety of students, and encourages support to maximise the individual potential of each student.

A good mentor is empathic and inspires students (Giglio et al, 1998). This is important in paramedic practice, as students need to feel valued and inspired in order to be encouraged to learn more (HCPC, 2014).

Conclusion

There is a significant lack of research into dyslexia among student paramedics. Critical analysis of the topic requires more research on the impact and on effective strategies for supporting both students and qualified paramedics undertaking professional development. This will hopefully develop over some years as the profession is increasingly recognised and quickly changing. As practical courses tend to attract a large number of dyslexic students it is likely that in higher education, paramedic educators will need to give dyslexia greater attention, as has happened in nursing (Nichols, 2012; Mortimore, 2013). The same applies for paramedic educators and mentors.

It is likely that dyslexic students will benefit from the provision of high quality and robust practice based education programmes; enabling better translation of theory into practice.

An inclusive learning approach will help all students so that dyslexics can also benefit. Education for mentors on ways to teach students might include using alternative kinaesthetic teaching methods; using non-white paper; providing practical learning; giving students time to read and speak; producing colourful material from which to learn; and supporting understanding of medical terminology.

Discussion with students about their dyslexia is key if they are willing to talk about their potential difficulties. It can remove stigma surrounding dyslexia and encourage other members of staff to learn from their example, and begin to recognise the learning difficulties that are common.

Performing a teaching exercise as part of mentor-training allowed me an insight into how dyslexic students can help mentors to teach. To prepare a lesson plan for a student with dyslexia takes longer than expected, and to create a style of plan to suit almost any form of dyslexia can be a challenge. If mentors do so for every student and create an inclusive learning environment, this might become the norm of mentorship all students benefit from. Perhaps this is what the paramedic profession needs: a new structure to the way we treat and observe our students. Broad-minded mentors can create broad minded students who will themselves go on to find new and innovative ways to teach future students.