Approximately 21% of the population in England and Wales are children under 18 years of age (Office for National Statistics, 2018). However, child health in the UK is considered inadequate compared with other European countries (Wolfe et al, 2014; 2017). With current epidemics in childhood obesity and mental health continuing to rise unaddressed by the government (Royal College of Paediatric and Child Health (RCPCH), 2020), poor child health not only significantly impacts the quality of childhood, but the wider economy as well (Blair et al, 2010).

For instance, obesity is thought to reduce life expectancy by 2–10 years depending on body mass index (BMI) (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), 2015), and increases the risk of chronic conditions such as type 2 diabetes, arthritis, and depression, where obese children will experience severe complications of these conditions by the age of 40 (Davies, 2019). The direct cost of obesity in terms of medical costs and productivity is 3% of the UK's GDP (approximately £60 billion in 2018), of which the cost to the NHS is £6 billion per year—5% of the NHS budget (Davies, 2019). Yet, 20% of children are obese by the age of 10 (NHS Digital, 2018), which is likely to continue through adulthood (Simmonds et al, 2016). Addressing childhood obesity therefore could not only reduce the cost and burden of obesity, but also improve life expectancy and minimise conditions associated with obesity.

Children in society have a right to healthcare and a healthy development to adulthood. Such rights are established under the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNICEF, 1989), which emphasises that every child should have the best possible health (article 24) and the right care for the circumstance (article 25). In order to achieve such goals, the role of child public health seeks to take action to improve the overall health of children and young people.

The subsequent series of articles aims to establish an overview of child public health, and the role and potential opportunities paramedics have in contributing to the field. This first article focuses on identifying what child public health is, the key strategies to effectively achieve a healthy life course from childhood and the role of the paramedic. The following three articles will then each delve further into the three core components of child public health:

What is child public health?

Blair et al (2010: 2) defines child public health as:

‘The art and science of promoting and protecting health and wellbeing and preventing disease in infants, children, and young people, through the skills and organized efforts of professionals, practitioners, their teams, wider organizations, and society as a whole’.

By achieving this definition and focusing on childhood health outcomes, it is thought that a healthy, developed child not only flourishes throughout the life course, but also improves the economy and reduces costs in healthcare (RCPCH, 2020). An example of this is the burden of mental health, where it is thought that 19% of children aged 5–14 and 31% aged 15–19 suffer from a mental health condition (Kossarova et al, 2016), which continues throughout adulthood, with links to violence, malnutrition, substance abuse, and affecting future education and employment status (Veldman et al, 2015; Reuben et al, 2016; Schaefer et al, 2017). Therefore, targeting mental health conditions that develop in childhood, is thought to be the best approach to reducing the overall burden of mental health and ensuing problems in society as a whole (Blair et al, 2010). This is more commonly known as the population paradox.

‘Reducing risk across a whole population can have a much greater impact than concentrating on high risk individuals. This is known as the population paradox’

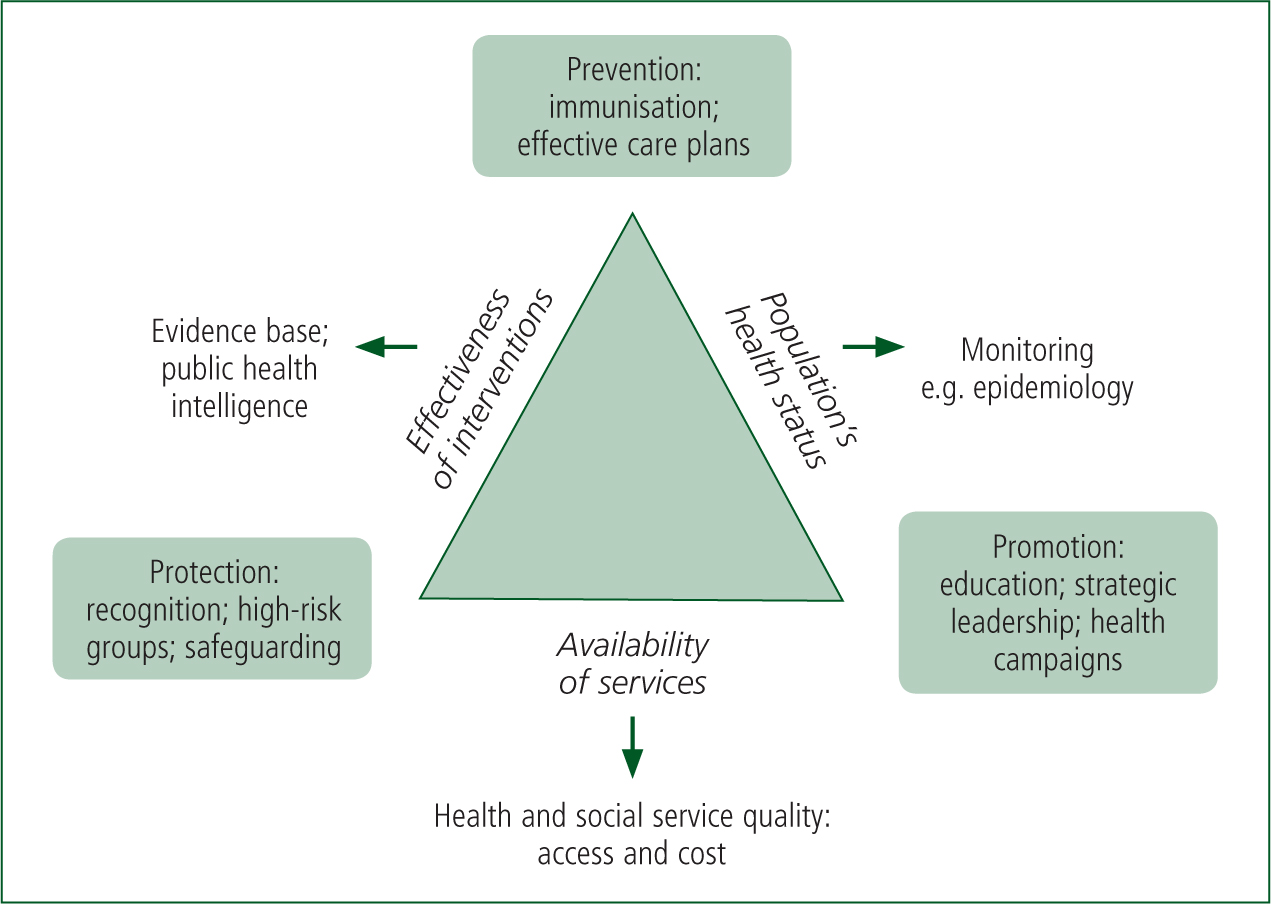

In order to achieve this, child public health seeks to uncover and monitor the prevalence of childhood diseases and high-risk groups such as children in families with low socioeconomic status, and develop techniques to prevent, promote, and protect children at a societal level (Blair et al, 2010).

Figure 1 depicts a visual strategy to identify needs and areas that require effective public health practice. A weakness in any area can result in a failure to influence and improve the health of children. Examples include poor adherence to the measles (MMR) vaccination, with recent increases in measles cases (lack of prevention and promotion); or reduced child and adolescent mental health funding despite the increasing epidemic of child mental health (British Medical Association, 2018).

Nevertheless, the NHS (2019) Long Term Plan has highlighted the need to focus on children, and the services children can access, both at hospital, and especially in the primary and community setting. Indeed, child public health strategies have successfully decreased emergency admissions for conditions such as epilepsy and asthma, and improved the management of diabetes (RCPCH, 2020). There is, however, still much to address in child public health, such as the lack of paediatric specialists within the community, complexities of child research and the limited evidence base in areas such as intervention.

A further criticism is the effectiveness of the population paradox approach, particularly when the focus is on an ageing population, where comorbidities tend to develop later in life (Suzman et al, 2015). Multiple longitudinal studies would be required to evidence the relationship of the effects of childhood on the elderly, which might be costly and impractical, given the rate at which technology and healthcare evolves during a lifetime. Thus, a pragmatic approach that focuses on known issues such as childhood immunisation, mental health, obesity, and poverty that have demonstrated an impact on adulthood remain key elements in child public health campaigns (RCPCH, 2020).

The role of the paramedic

Clearly, Blair et al's (2010) concept of public child health highlights that professionals, organisations and their practitioners are key elements, where paramedics are no exception. Paramedics encounter children both in ambulance and primary care organisations, and already contribute towards child public health by:

Arguably, much of the role of the paramedic, particularly in the ambulance service, has traditionally been to act as a safety net for children where preventative measures have failed; for instance, being dispatched to emergencies such as life-threatening asthma attacks, gang-related stabbings, acute mental health crises, or possible sepsis. However, since the Urgent and Emergency Care Review (NHS England, 2015) with the development of ‘hear and treat’ within 111, and the growing paramedic specialisms in primary and urgent care (College of Paramedics, 2019), the paramedic profession needs to develop a deeper understanding of its role and capability within child public health (and public health in general) beyond the ambulance service.

Certainly, paramedics in community settings, including within the ambulance service have a unique role in directly accessing children in the family environment, providing a direct opportunity to identify children who are in vulnerable, high-risk groups; facilitate better access to healthcare services; collect and collate community data; as well as provide opportunities to educate families in promotional and prevention strategies. Table 1 offers a summary of the potential paramedics have to contribute to child public health, some of which may already be in place depending on the local commissioning group.

| Paramedic within ambulance service | Paramedic within primary and urgent care |

|---|---|

|

|

|

| Across both sectors | |

|

|

|

Conclusion

This article briefly introduces child public health, the population paradox in promoting a healthy life course, and the importance each element has on an effective public health strategy, as well as the role of the paramedic in child public health.

Paramedics are already involved in child public health; however, the profession has more potential to contribute to child public health strategies. The following articles will focus on the three main topics of child health—prevention, promotion, and protection—and delve further into the role of paramedic practice in improving current issues faced in child public health.