The ambulance service has always recognised that the sooner a clinician is with a patient and clinical interventions are performed the greater the chance of survival. This seems simple enough and is what every ambulance service throughout the world does each and every day; however, what if that patient is in a collapsed structure, contaminated environment, at height or in an area of flooding?

The Hazardous Area Response Team (HART) was created to overcome these problems, as previously the ambulance service relied on fire and rescue service (FRS) colleagues to bring casualties to them, which would cause an obvious delay in treatment.

The simple solution would be to increase the level of skills that a fire fighter has, but the training for a modern paramedic takes 3–4 years, with constant patient contact during that time being the order of the day. The days of simple interventions and transport to hospital are a thing of the past. Today's paramedic has a foundation degree in paramedic science and a level of clinical knowledge and skills that are the envy of the world in that they have a wide range of skills and are autonomous in their clinical practice. The HART programme takes the personal protective equipment used by FRS to deliver the clinician to the patient—wherever they may be.

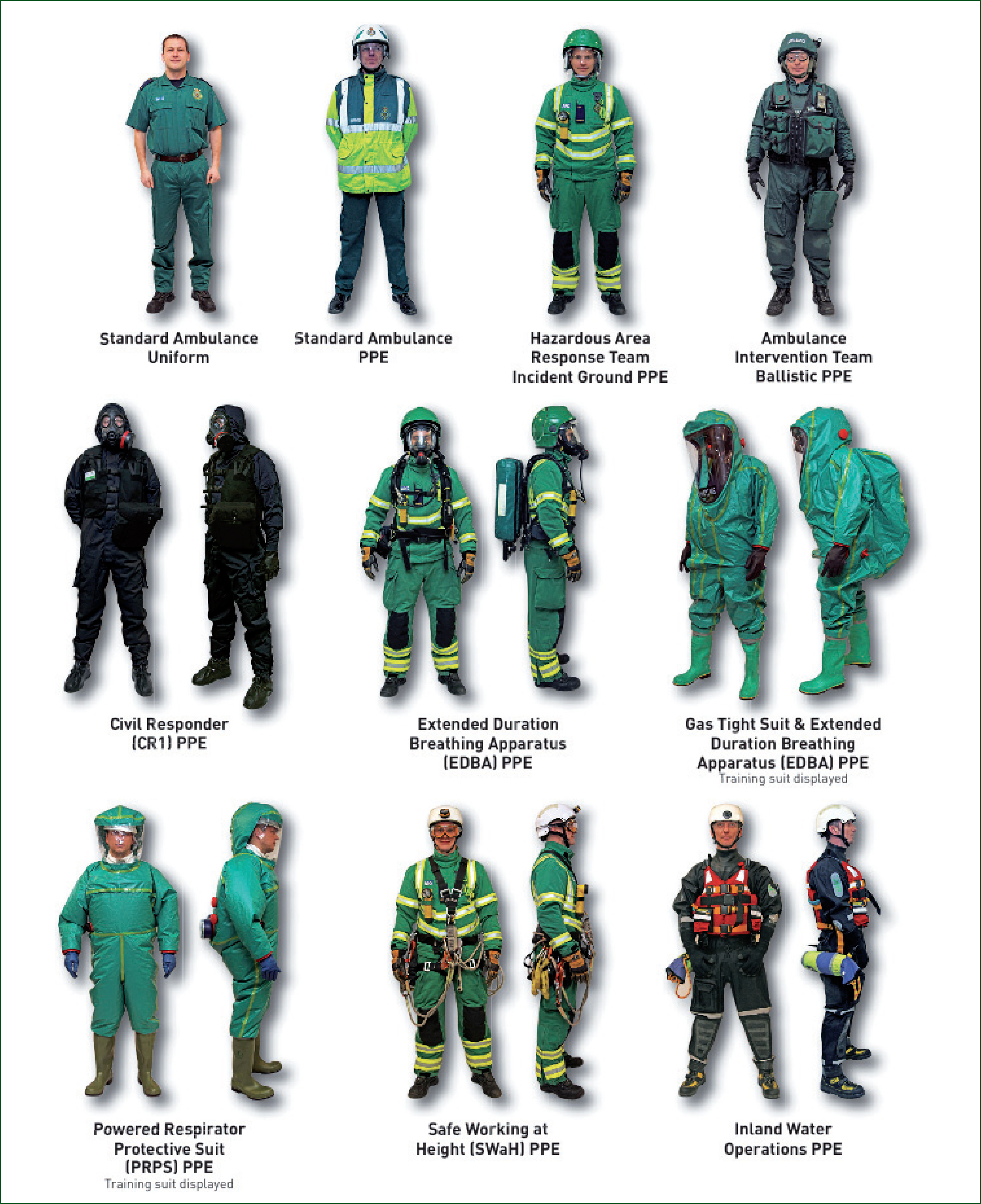

HART has four main areas of operation and utilises different types of PPE to enable the paramedic to enter the hazard area and provide treatment accordingly. All team members have the same skills, with each team consisting of 42 staff divided into 7 teams of six providing a 24/7 response. The amount of skills each team member has to cover for the four operational areas means that a dedicated training week is required every seven weeks. This is also paramount due to regulatory and legislative compliance that is required due to the areas of work for HART and the associated PPE.

‘The challenges to the HART paramedic remain the same and that is to deliver timely patient care in a challenging environment’

The first area of operation concerns environments contaminated accidentally, such as with hazardous materials, Hazmat, or from a deliberate release of chemical, biological, radiological or nuclear (CBRN) materials. The challenges to the HART paramedic remain the same and that is to deliver timely patient care in a challenging environment. The PPE used in these areas includes Extended Duration Breathing Apparatus (EDBA) and the NHS PPE, Powered Respirator Protective Suit (PRPS). HART also uses Civilian Responder One (CR1) when working with the police as required. All of these types of PPE greatly limit dexterity and yet prime concerns will be to follow the <C>ABC paradigm of treatment. Catastrophic haemorrhage is dealt with through the use of combat application tourniquet before securing the airway using an i-gel, which can be coupled with a VR1 closed circuit ventilator. To provide a drug route, HART use EZ-IO, which has been used extensively by the military and is now seeing more widespread use within ambulance services in the UK. The patient is then packaged as required and removed to the Warm Zone, where treatment can continue or the process of decontamination can be commenced if required.

The next area of operation for HART is urban search and rescue (USAR). This includes collapsed structures, working at height or within confined spaces. All of these areas are highly regulated by the Health and Safety Executive and this is reflected in the training that HART receives and the development of its own instructor capability for safe working at height (SWaH). The environments are less restrictive and so with regards to clinical interventions, portability is more the order of the day and so HART has dedicated packaging systems that can be inserted into a rope or pulley system to transport them to the patient. The main challenge for HART is extrication of the patient and so the teams use a multi-integrated bodysplint stretcher (MIBS). It is completely metal free and so can be used in combustible atmospheres and the patient can be extricated within an established rope system as MIBS is subject to Lifting Operations and Lifting Equipment Regulations 1998. HART, along with wider ambulance Trusts also use a mass oxygen delivery system that can treat up to 48 patients in one go but also, in the USAR environment, pump the oxygen up to 150 metres away in to a collapsed structure to treat four individual patients. Should the patient require a significant amount of time to extricate and, for example, have a penetrating chest injury and developing pneumothoraces, then this can be corrected by needle thoracentisis or a chest drain. In these situations the IT that supports HART can be brought into play by taking a camera to the patient, beaming that live video to a doctor who can then support and advise the paramedic if/as required.

The PPE used within USAR consists of the obligatory helmet, as well as a safety harness and energy absorbing lanyard in case the HART paramedic should fall. Confined space is heavily regulated and due to the unstable nature of collapsed structures with the ever-present risk of further collapse and a loss of air, HART uses SavOx. This device is not new and has been used by the mining industry for a very long time. SavOx supplies oxygen to the HART Paramedic for at least 30 minutes to enable them to extricate themselves. The principle of generating oxygen from the chemical potassium superoxide (KO2) provides an oxygen supply controlled by the user's consumption.

Inland water operations is the third area of HART Operations and was introduced following the Pitt Review in 2007, which showed that the emergency services needed to be better prepared for mass flooding. The skill levels and associated training were designed by the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA), along with the fire and rescue service. HART are trained to DEFRA Level 3, which is also known as water rescue technician. This allows HART to form part of a team, be that FRS or an NGO, that are deployed on a boat. HART do not possess boats but need to have the skills to meet the DEFRA requirement to work on one and from there gain access to patients accordingly. The flooding of 2007 showed that communities over a large area can be cut off and those with existing medical conditions or the elderly will need treatment from a clinician. The PPE used by HART is standard with other agencies for working in or around water, consisting of a dry suit, personal floatation device (PFD) and a helmet. At present, the required helmet colour for DEFRA Level 3 is red and is universally recognised, but HART are working to add green to the guidance which will denote a HART Paramedic who is a water rescue technician. The water environment is fully permissive with regards to patient treatment but the main problem is keeping all the equipment dry—an ECG that falls overboard is certainly frowned upon! HART uses different types of roll-top dry bags to transport its equipment to the patient and also uses 15 metre throw lines for upstream and downstream safety.

The fourth and final area of operation for HART involves firearms. Events in Mumbai and, more recently Nairobi, have shown a shift in terrorist methodology, and whilst the conflict waged between Kenya and neighbouring Somali by Al Shabaab may be considered only to be an African-related situation, the threat none-the-less remains. HART paramedics and other specialist groups have access to ballistic PPE to operate in these types of scenarios to provide patient care as soon as possible to increase survivability for those caught up in these types of incidents. The aim from a clinical point of view is to treat, and where possible extricate, the patients using simple but proven interventions such as CAT tourniquet, blast bandages and chest seals.

It is important to note that the concept of operations for HART is to enhance the existing rescue capabilities provided by other agencies by adding an NHS paramedic component. We now have an evidence base through the NHS and the military that early intervention by a paramedic will improve the patients and outcome and survivability—wherever they may be.