Stroke is a medical emergency and a significant clinical event. In England and Wales almost 90,000 individuals are hospitalised annually with an acute stroke, 85% of which are ischaemic in nature, 10% due to primary haemorrhage and 5% due to subarachnoid haemorrhage.

Stroke deaths account for 11% of all deaths (RCP, 2016) and whilst the majority of individuals survive their first stroke; the risk of suffering a second stroke within 5 years is 26% and 39% by 10 years (Mohan & Wolfe et al, 2011).

Due to improvements in care, the majority of patients survive their first stroke, although with significant resulting morbidity. Currently in England, 900,000 people are living with the effects of stroke, with 50% dependent on other people for help with everyday activities and stroke remains the largest cause of disability in the UK (Mackay & Mensah, 2004). Stroke has a large burden in the health economy, estimated to cost the NHS around £3bn per year, with additional cost to the economy of a further £4bn in lost productivity, disability and informal care (NHSE, 2017)

A key element in the successful treatment of acute stroke patients is the rapid but accurate assessment of the patient in the pre-hospital setting and prompt alerting the relevant Emergency Department (ED) or neurosurgical centre, as appropriate, that a suspected stroke patient is in your care. The current UK Ambulance Service Clinical Practice Guidelines refer specifically to treatment for identification or management for acute stroke and TIA and will be referenced accordingly (AACE, 2016).

What is a stroke?

The World Health Organization (WHO) defined a stroke as a ‘a clinical syndrome consisting of rapidly developing clinical signs of focal (or global in case of coma) disturbance of cerebral function lasting more than 24 hours or leading to death with no apparent cause other than a vascular origin’ (Hatano, 1976). A Transient Ischaemic Attack is defined as stroke symptoms and signs that resolve within 24 hours. However there are some notable limitations to these definitions; TIA symptoms usually resolve within minutes, or a few hours at most, and anyone with continuing neurological signs when first assessed should be assumed to have had a stroke.

The acute focal injury of a stroke results from a disruption to the vascular supply in the brain, caused either by haemorrhage or ischaemia. The reduction in blood flow and/or volume depletes the brain of oxygen and nutrients, ultimately leading to cell death. Depending on the origin of the assault, physical, mental and cognitive disabilities and impairment can follow. Strokes can be either ischaemic (85%) or haemorrhagic (15%) in origin. Strokes have previously been referred to as cerebrovascular accident (CVA), cerebrovascular insult (CVI) or brain attack. None of these terms are accurate and should no longer be used. A stroke should either be referred to as a stroke or a TIA.

Stroke and TIA risk factors

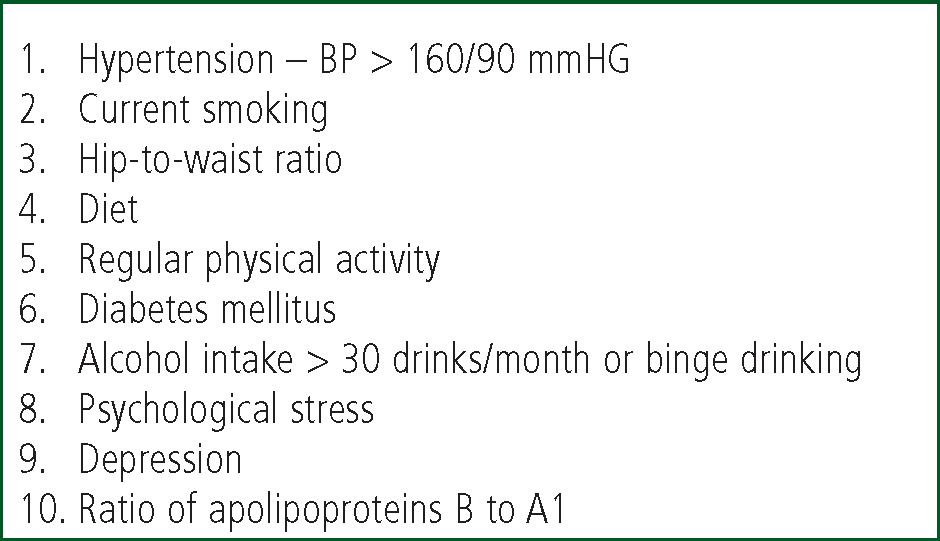

The major risk factors for strokes and TIAs are comparable to those for other cardiovascular disease and include hypertension, tobacco use, Atrial Fibrillation (AF), heart failure and acute myocardial infarction (AMI) (Mackay & Mensah, 2004). The large INTERSTROKE study reviewed first strokes in 22 countries over a 3-year period and identified a number of risk factors associated with 90% of strokes (see Figure 1). In intracerebral haemorrhagic strokes, the risk factors included hypertension, smoking, waist-to-hip ratio, diet, and alcohol intake (O'Donnell, Xavier & Liu et al, 2010).

It is worth briefly exploring the key risk factors for stroke and TIA, as both conditions frequently present in the pre-hospital setting. Hypertension and Atrial Fibrillation are common – paramedics are in a unique position to discuss these conditions with patients in their care.

Hypertension

The key risk factor in stroke is hypertension (HTN), defined as a sustained blood pressure of 140/90 mmHg or higher (NICE, 2011, The British Hypertension Society, The National Collaborating Centre for Chronic Conditions). HTN is the biggest single risk factor for premature death and disability in England; 25% of UK adults are diagnosed as hypertensive. HTN is frequently asymptomatic, with an estimated 5 million people in the UK who are currently unaware of their HTN diagnosis - often referred to as the ‘silent killer’. The financial costs are significant; Public Health England estimated the cost of HTN treatment within the NHS as £2 billion annually (PHE, 2014).

Fortunately HTN is one of the most modifiable risk factors for both ischaemic and haemorrhagic strokes (Tu, 2010, Gorelick, 2002, Pistoia & Sacco et al, 2016). An estimated 25% of strokes may be attributable to HTN and reducing BP considerably lowers the stroke risk (Aiyagari & Gorelick, 2009). Studies demonstrated that for each 10 mmHg reduction in systolic blood pressure, stroke risk is reduced by approximately 30% in individuals aged 60 – 79 years (Lawes, Bennett & Feigin et al, 2004). Further evidence demonstrated that antihypertensive therapy is important for prevention of stroke, regardless of age, gender, or ethnicity (Johnston, Sidney & Hills et al, 2010).

Atrial Fibrillation (AF)

Analogous to HTN, it is estimated a significant percentage of patients are unaware of their AF diagnosis. Up to 18% of patient may unknowingly be affected, with a further 25% of patients suffering Type 2 diabetes mellitus. Both diseases are frequently only diagnosed following an acute, life-threatening event such as a stroke, at this stage, the majority of vascular damage has already commenced (RCP, 2016).

AF is particularly hazardous; presenting a 5-fold risk of stroke, with one in five strokes attributed to this arrhythmia. Evidence suggests an increasing incidence, of AF, particularly in men and the elderly (Stewart, Hart & Hole et al, 2001 & Go, Hylek & Phillips et al, 2001) and AF prevalence is expected to double within the next 50 years. AF. AF is caused by chaotic electrical activity; resulting in ‘absolutely’ irregular RR intervals within the atria, subsequently overriding the sinus node (NICE, 2014). Acute stroke is often the first presentation of AF, as AF is frequently asymptomatic. Pharmacological management of AF includes anticoagulation and antiarrhythmics. Non-pharmacological management includes electrical cardioversion and ablation (NICE, 2014). Ideally, any episode of suspected AF should be recorded by 12-lead ECG of sufficient duration and quality to evaluate atrial activity.

Pre-hospital stroke assessment

Rapid and accurate assessment of a potential stroke patient is essential in early stroke diagnosis. An estimated 1.2 billion neurons and 8.3 trillion synapses can be lost during an ischaemic stroke, accelerating aging by an estimated 36 years (Saver, 2006).

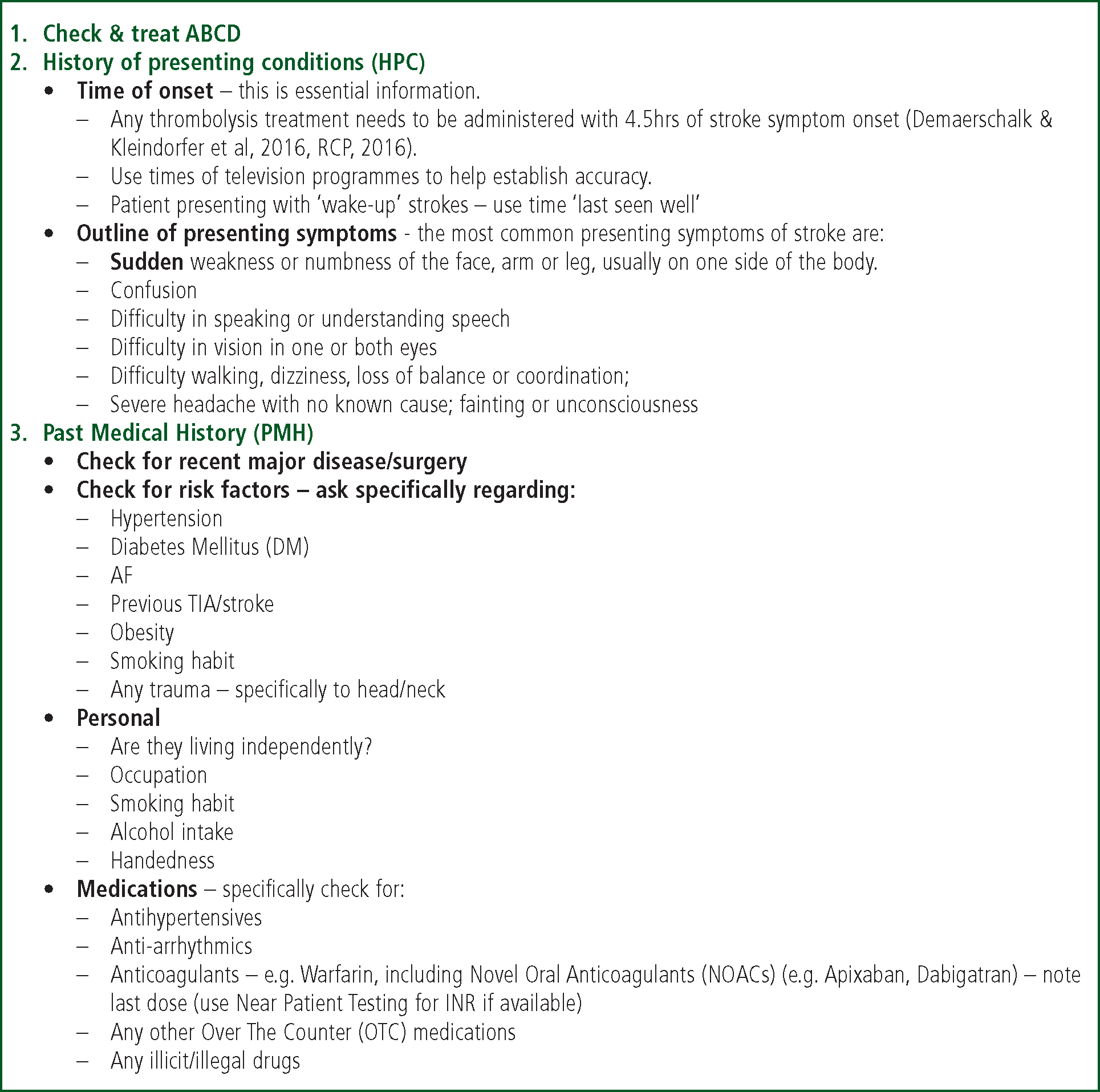

Therefore a rapid, concise patient history is key to gather information, either from the patient themselves or relatives/passersby. Supplemental oxygen can be administered if the suspected stroke patient is hypoxaemic (e.g. SpO2 < 94%) (AACE, 2016). The suggested key aspects of assessment for a suspected stroke patient are outlined in Figure 3.

The key features of acute stroke are the sudden onset of focal neurological sings and symptoms (focal – referring to focal neurological functions such as brain and spine). The presence of positive symptoms, for example ‘pins and needles’, flashing lights are not usually symptomatic of a stroke.

Key features of a stroke:

Differential diagnosis & stroke mimics

Stroke has a number of potential differential diagnoses, including stroke ‘mimics. Table 1 lists the differential diagnosis of patients presenting in ED with stroke or TIA, with a final diagnosis of non-stroke or non-TIA (Gibson & Whiteley, 2013).

| Differential Diagnosis | % reported final diagnosis other than stroke/TIA |

|---|---|

| Seizure | 19.6% |

| Syncope | 12.2% |

| Sepsis | 9.6% |

| Benign headache disorder | 9.0% |

| Brain tumour | 8.2% |

| Functional | 7.4% |

| Metabolic | 6.2% |

| Non specific | 5.0% |

| Neuropathy | 4.6% |

| Dementia | 2.3% |

| Extra/subdural haemorrhage | 1.8% |

| Drugs/alcohol | 1.6% |

| Hypertension related | 0.9% |

| Encephalopathy | 0.5% |

| Trauma | 0.5% |

Mimics

Stroke mimics, also referred to as ‘stroke chameleons’, are non-vascular disorders imitating stroke and may be indistinguishable from an ischemic stoke syndrome (Huff, 2014) have been a reported 31% misdiagnosis rate by physicians in the hospital (Kothari & Barsan et al, 1995).

CT scanning has aided the clinical differentiation between ‘true’ strokes and mimics, which can range from 2.8% (Winkler, Fluri & Fuhr et al, 2009) to 21% of patients who were subsequently diagnosed as non-stroke (Chernyshev, Martin-Schild, & Albright, et al, 2010). Evidence also suggests that stroke mimics tend to be younger, female patients with less severe ‘stroke’ symptoms (Tsivgoulis, Alexandrov & Chang et al, 2011). However patients receiving intravenous thrombolysis, subsequently confirmed as a stroke mimic, did not suffer undue side effects, such as haemorrhage (Chernyshev & Martin-Schild et al, 2010 & Guerrero & Savitz, 2013)

Specific overview of stroke mimics

The majority of stroke mimics are commonly presenting conditions to the ambulance service, and whilst stroke should always be considered as a provisional diagnosis, an awareness of potential mimics is a useful overview.

Migraine

Migraine is a common, chronic, multifactorial neurovascular disease, often characterized by severe headache and autonomic nervous system dysfunction (Spalice & Del Balzo, 2016). Migraines often affect younger patients and can be hemiplegic in nature. Patients often report a family history of migraine, which can occur with or without headache. Some patients experience unusual sound/tastes, auras, even dysarthria and dysphasia. Some patient may also present with paraesthesia (‘pins and needles’) in one or more limbs.

Sepsis

Studies reporting incidence rates for sepsis vary from 9.6% (Gibson & Whiteley, 2013) to 12.8% (Hand & Kwan, 2006) for patients initially presenting as a stroke, later diagnosed with sepsis. Hand & Kwan (2006) also reported the most frequent site of sepsis was the chest. Key signs and symptoms of sepsis include altered mental status, hyperglycaemia without a DM diagnosis, tachypnoea (<25/minute), altered temperature (<38°C or > 36°C), tachycardia (<130/minute) and hypotension (>90mmg Hg systolic or >40mmHg below normal BP) (NICE, 2016a, AACE/JRCALC, 2016 & Smith & Massaro, 2015).

Seizure

Seizures and post-seizures are frequently reported stroke mimics. Post-ictal weakness is often referred to as Todd's Paralysis (or palsy) but can present as a complication of acute stroke (Abbott, Bladin & Donnan, 2001) and account for almost 20% of stroke mimics (Smith & Massaro, 2015). Stroke-like symptoms following seizure resolve within minutes (up to several weeks on occasion) and they a history of seizures is a key indicator for this stroke mimic (Walker, 2011). In seizures caused by hypoglycaemia, current guidelines recommend the administration of glucose or 10% glucose intravenously (AACE, 2016).

Hypoglycemia

Transient hypoglycemia can produce stroke-like symptoms, including hemiplegia and aphasia. Diagnosed diabetic patients can present with neurological deficit, in addition to occasional imaging abnormalities with 20% mimicking acute ischaemic stroke (Young, Morris & Shuler et al, 2013). Hypoglycemic patients can present with drowsiness, confusion even coma, highlighting the importance of blood glucose assessment. Current ambulance service guidelines recommend the oral administration of quick acting carbohydrate for blood glucose <4.0 millimols/litre) or 10% IV glucose in more severe cases, although this should not delay on-scene time (ACCE, 2016).

Lesions

Subdural hematoma, primary and metastatic tumours and cerebral abscesses are common stroke mimics and rapid symptoms onset includes headache, nausea, vomiting and visual changes, diagnosed by CT scanning (Smith & Massaro, 2015). A study by Hatzitolios, Savopoulos & Ntaios et al (2008) identified a 5% incidence of primary or secondary tumour in suspected stroke patients; whilst other studies have revealed a lesion incidence of <1% (Förster, Griebe & Wolf et al, 2012).

Functional haemiparesis

Patients can present with functional symptoms, also referred to as psychosomatic or conversion disorder, although there is less evidence regarding this presenting mimic. Functional diagnosis should only be considered once other diagnoses have been discounted. One study of ED presentations of conversion disorder noted that symptoms of paresis, paralysis, or movement disorders were common and were a presentation in almost 30% of patients (Dula & DeNaples, 1995). These patients have a noted significant comorbidity; often other psychiatric disorders, and conversion disorder diagnosis is one of exclusion, with multiple diagnostic tests required prior to a conclusive diagnosis (Huff, 2014).

Others mimics

Other potential differential diagnosis include:

Clinical examination in ED

A frequent complaint of paramedics is the lack of awareness of the patient's final diagnosis. Often due to workload, once patients have been handed over to ED staff, paramedics are being advised of their next patient. This section with provide an overview of the ongoing hospital assessment to address this including:

Stroke Assessment Tools

Three of the specific stroke assessments will be discussed here, including the ROSIER Scale, the National Institute of Health Stroke Scale and the modified Rankin Scale. Although undertaken in ED, it is useful for paramedics to have an awareness of these specific tests.

One aspect of the FAST assessment tool is the lack of specificity; FAST originally developed to raise public awareness for contacting the emergency services immediately in case of a suspected stroke. Harbison & Hossain et al (2003) reviewed studies related to other pre-hospital stroke assessment tools, including the Cincinnati Prehospital Stroke Scale (CPSS) (Kothari & Pancioli et al, 1999), the Los Angeles Prehospital Stroke Screen (LAPSS) (Kidwell & Starkman, 2000) and the FAST test. They concluded as none of these techniques detected visual field defects or disorders of perception, balance, and coordination, they were therefore insensitive to posterior cerebral circulation lesions (Table 2 provides an overview).

| Technique | Sensitivity | Specificity | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

FAST

|

|

79 - 85% | 68% |

|

CPSS

|

|

44 – 95% | 23 – 96% |

|

LAPPS

|

|

74 – 98% | 44 – 97% |

|

ROSIER

|

|

80 – 90% | 79 – 83% |

|

CPSSS

|

44 – 95% | 23 – 96% |

ROSIER scale

The Recognition of Stroke in the Emergency Room (ROSIER) scale is a 7-item stroke tool incorporating elements from the FAST tool but include leg weakness and visual field deficit (Nor & Davis et al, 2005). If a patient scores 1 for each element, this is indicative of a stroke. ROSIER also includes assessment of loss of consciousness, syncope and seizure activity, both reducing the likelihood of a stroke. A ROSIER score (see Table 3) of ≥1 suggests a stroke or TIA whilst a score of ≤0 indicates non-stroke.

| Is there loss of consciousness or syncope? | Yes (1) | No (0) | Unable to assess |

| Has there been seizure activity? | Yes (1) | No (0) | Unable to assess |

| Is there NEW ACUTE onset? | 9.6% | ||

| Asymmetrical facial weakness | Yes (1) | No (0) | Unable to assess |

| Asymmetrical arm weakness | Yes (1) | No (0) | Unable to assess |

| Asymmetrical leg weakness | Yes (1) | No (0) | Unable to assess |

| Speech disturbance | Yes (1) | No (0) | Unable to assess |

| Visual field defect | Yes (1) | No (0) | Unable to assess |

| Total score: -2 - +5 |

The ROSIER score assesses facial, arm, or leg weakness, speech, and visual field deficits. Blood glucose must be >3.44mmol/l. Scores range from -2 to 5 with a score less than or equal to zero indicating a low likelihood of stroke. Seizure or syncope is scored as -1.

Fothergill & Williams (2013) reported that physicians confirmed 64% positive predictive value (compare 62% for FAST) strokes and 78% non-stroke identified by ambulance clinicians using ROSIER (Confidence Interval of 95% for both tools).

NIHSS scale

The National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) is a systematic assessment tool providing a quantitative measure of stroke-related neurologic deficit. Originally designed as a research tool for a clinical trail, it is now the most widely utilised measure of stroke acuity within the in-hospital setting. The NIHSS tool comprises of 15 ‘items’, including evaluating consciousness, language, neglect and visual fields. The NIHSS tool takes approximately 7-10 minutes to complete, with current opinion suggesting this is too lengthy for pre-hospital practice. Essentially the lower the NIHSS score, the less severe the stroke. However the validity of the scale is dependent on the accuracy of the observer. An example of the modified NIHHSS scale can be seen at http://www.mdcalc.com/modified-nih-stroke-scale-score-mnihss/

Modified rankin scale

The Modified Rankin Scale is a much simpler tool and is used to categorize level of functional independence with reference to pre-stroke activities rather than on observed performance of a specific task (see Table 3).

Transient Ischaemic Attack (TIA)

A TIA is defined as stroke symptoms with completely resolution within 24 hours. A specialist should assess all TIA patients within 24 hours of symptom onset (NICE, 2008) as approximately 15% of ischaemic strokes are preceded by a TIA (Hankey, 1996). TIAs are considered as a warning event and require rapid access to the appropriate care. High-risk TIA patients require brain imaging if being considered for carotid endarterectomy, if symptoms were prolonged, patients on anticoagulants or to rule out other diagnoses (NICE, 2008). A Canadian study reported that the risk of stroke following TIA was 9.5% at 90 days and 14.5% at 1 year, with a combined risk of stroke, myocardial infarction and death at 21.8% at 1 year (Hill & Yiammakoulias et al, 2004)

Treatments for Acute Ischaemic Stroke

Recent developments in the treatment of acute stroke include thrombolysis and thrombectomy, both of which will be briefly discussed.

Thrombolysis

Prompt treatment with thrombolytic drugs can restore blood flow prior to major cerebral damage has occurred in acute ischaemic stroke, which represents 85% of all stroke presentations. The thrombolytic therapy administered in the UK is Alteplase, intravenous recombinant tissue plasminogen activator (rt-PA), evaluated in several randomised controlled trials. Initially UK licensing agreements included patients aged up to 80 years of age administered within 3 hours of symptom onset (NICE, 2008). A later European study extended the timeframe for administration to 4.5 hours and the upper age limit of 80 discounted (IST-3, 2012).

Thrombectomy

Mechanical thrombectomy is a relatively new treatment in the UK for patients suffering a severe stroke, licensed to treat large vessel occlusion in the US and Europe (NHSE, 2017). Thrombectomy treatment comprises intra-arterial catheterisation to the level of occlusion followed by delivery of a thrombolytic agent, mechanical thrombectomy, or both in specialist neuroscience centres. This procedure is conducted with either local or general anaesthetic in a specialised centre. A multicentre study demonstrated that mechanical thrombectomy is superior in safety terms, with a greater efficacy rate than intravenous thrombolysis alone. Significant fiscal savings were reported due to reduced patient disability and length of hospital stay (Berkhemer & Fransen et al, 2015). An estimated 8,000 patients annually could benefit from the new treatment, which needs to be delivered within 6 hours of symptoms onset. The 24 neuroscience centres proposed in England are gradually opening, however the service currently remains largely limited across England (NHSE, 2017).

| Level | Description |

|---|---|

| 0 | No symptoms |

| 1 | No significant disability, despite symptoms; able to perform all usual duties and activities |

| 2 | Slight disability; unable to perform all previous activities but able to look after own affairs without assistance |

| 3 | Moderate disability; requires some help, but able to walk without assistance |

| 4 | Moderately severe disability; unable to walk without assistance and unable to attend to own bodily needs without assistance |

| 5 | Severe disability; bedridden, incontinent, and requires constant nursing care and attention |

Acute Haemmorrhagic Stroke

Treatment for acute haemorrhagic strokes, which account for 15% of strokes, depends on the level and location of bleed. Patients suffering intracranial haemorrhage (ICH) require specialist monitoring in a neurosurgical centre, with access to brain imaging. Patients diagnosed with middle cerebral artery infarctions, meeting the criteria below, should be considered for decompressive hemicraniectomy and referred within 24 – 48 hours of symptoms onset (NICE, 2016b):

Conclusions

Stroke is now recognised as a medical emergency with over 110,000 cases in the UK annually. 20 – 30% of stroke patients die within 30 days of their stroke with survivors living with a range of disabilities. Treating stroke patients costs the NHS £2.8 billion annually. The most significant modifiable risks for stroke are hypertension, atrial fibrillation and diabetes mellitus – commonly occurring in an increasingly aging population. The key features of acute stroke are the sudden onset of focal neurological sings and symptoms. The presence of positive symptoms, such as pins and needles and flashing lights are not usually a stroke diagnosis. Several assessment tools exist to help diagnose stroke, including the NIHSS scale. Kwan & Hand et al (2004) suggested that education should be aimed at paramedics and ED staff in improving the accuracy of stroke identification and ensuring rapid transfer to the hospital. Specific education of paramedics increases knowledge of stroke, clinical and communication skills and decreases pre-hospital delays.

The ability of paramedics to recognise stroke recognition and pre-alert hospital are associated with shorter pre-hospital times, highlighting the importance of including ambulance practice in comprehensive care pathways that span the whole process of stroke care (Mosely & Nicol et al 2007). Rapid assessment and transfer to specialist stroke centre is key to a positive outcome for stroke patient. Finally, Sheppard & Mellor et al (2015) suggested that providing a hospital pre-alert message was an influential factor in facilitating timely assessment for acute stroke patients upon arrival in hospital. Communication is everything!