Diabetes mellitus is one of the most common and important medical conditions in the UK (Diabetes in the UK, 2010). Hypoglycaemia is the most common diabetic emergency (Brackenridge et al, 2006). It is a major obstacle in achieving the tight glycaemic control required to prevent the long-term complications of diabetes (Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Research Group (DCCT), 1993). Prolonged hypoglycaemia can result in severe neurological and psychosocial morbidity and even death. Prompt and effective treatment is therefore essential in preventing the associated significant morbidity and mortality. The diagnosis and treatment of hypoglycaemia is commonly encountered by paramedics.

Case study

A 42-year-old gentleman called 999 after taking an insulin overdose. On arrival at his house, paramedics found him ambulant and conversant, but confused (Glasgow coma scale (GCS) 14/15; Eyes 4/4; Verbal 4/5; Motor 6/6). Initial examination found that his airway was patent and he was haemodynamically stable. Capillary blood glucose (CBG) was low (3.2 mmol/L). Observation of the scene revealed empty cartridges of glargine (cumulative total of 1500 units of insulin), three empty cans of lager, and five empty 500 ml bottles of Lucozade®. The paramedics administered 20 ml of Hypostop® (40% glucose gel), before gaining large bore intravenous (IV) access and administering 5% glucose solution.

In the ambulance, further history was obtained. The patient had been diagnosed with type 1 diabetes mellitus 12 years previously. He was maintained on a basal bolus regime (Novo Rapid® 8-18 units short-acting insulin with each meal, and glargine 30 units long-acting insulin at night). He did not have any other medical diagnoses and was not taking any other medications. He had suffered from low mood for some time, but had not sought medical help for this. This was his first attempt at self-harm. The previous day he had drunk three 500 mls cans of normal strength lager, and subsequent to this had injected 1500 units of insulin into one site on his abdomen. The intention had been to commit suicide.

Upon awaking the next morning, he had symptomatic hypoglycaemia (he felt tired and confused) and so drank lucozade®. The symptoms continued and so he drank further bottles of lucozade. After five bottles (a total of 345 g glucose), he was still symptomatic, and called the ambulance service (some 18 hours post-overdose).

During his hospital inpatient stay, he was able to eat and drink. Alongside the enteral nutrition, he received ongoing parenteral 10% dextrose infusions. In hospital, the patient suffered from a number of hypoglycaemic episodes. These were usually after an attempt to stop the dextrose infusion and maintain CBG on oral support alone. The last recorded hypoglycaemic event (CBG 3.7 mmol/L) was 84 hours post-overdose, and occurred after a two-hour cessation of the IV dextrose. The dextrose infusion was successfully withdrawn 108 hours after the overdose. The equivalent of 26 L of 5% dextrose had been administered.

Excision of the injection site was not deemed necessary as CBG was maintained at a safe level with oral and parenteral support. Random cortisol level was checked, and found to be normal (adrenal failure is a cause for persistent hypoglycaemia). The patient was reviewed by the mental health services prior to discharge.

This case highlights the long action of insulin glargine in the case of massive overdose, even in an otherwise healthy patient. It also emphasizes the importance of vigilance with ongoing CBG monitoring, especially upon attempted withdrawal of IV dextrose. Another point to consider is the delayed onset of initial hypoglycaemia and the need to monitor CBG for at least 24 hours post-overdose of long-acting insulin analogues.

Incidence

Most commonly, hypoglycaemia occurs in diabetic patients managed with insulin or sulphonylureas. Data from the DCCT suggest that 10% of patients, with type 1 diabetes mellitus on standard insulin therapy, experience at least one episode of hypoglycaemia requiring medical attention each year (DCCT, 1993).

More recent data from the UK Hypoglycaemia Study Group showed an incidence of severe hypoglycaemia of 110 episodes per 100 patient years in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus for less than 5 years, and 320 episodes per 100 patient years in those with disease less than 15 years (UK Hypoglycaemia Study Group, 2007).

On more intensive insulin regimes, this risk increases up to threefold (DCCT, 1993). In type 2 diabetes mellitus, severe hypoglycaemia is less common. However, it is still a clinically significant problem. A recent large multi-centered trial showed that patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus on insulin treatment had 1.8 episodes of hypogylcaemia per year (UK Prospective Diabetes Study (UKPDS), 1998).

In addition, 30% of hypoglycaemic episodes in type 2 diabetic patients will require hospital admission, compared to 10% of type 1 diabetics (NHS Diabetes, 2010). Furthermore, there is an increased frequency and severity of hypoglycaemic episodes in the elderly, patients with renal impairment, and those with long standing diabetes (NHS Diabetes, 2010).

Patients with both type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus have nearly twice the risk of developing depression compared to the general public (Rush et al, 2008). Despite this, only 30-50% of diabetics are recognized as suffering from depression (Katon et al, 2004; Katon, 2008).

In a UK cohort, individuals with type 1 diabetes mellitus had eleven times the suicide rate, compared with the general population (Roberts et al, 2004). Published data on the frequency of suicide attempts using insulin is sparse. However, one small retrospective case-series found that nearly 90% of insulin overdoses were either suicidal or parasuicidal (von Mach et al, 2004).

‘This case highlights the long action of insulin glargine in the case of massive overdose, even in an otherwise healthy patient’

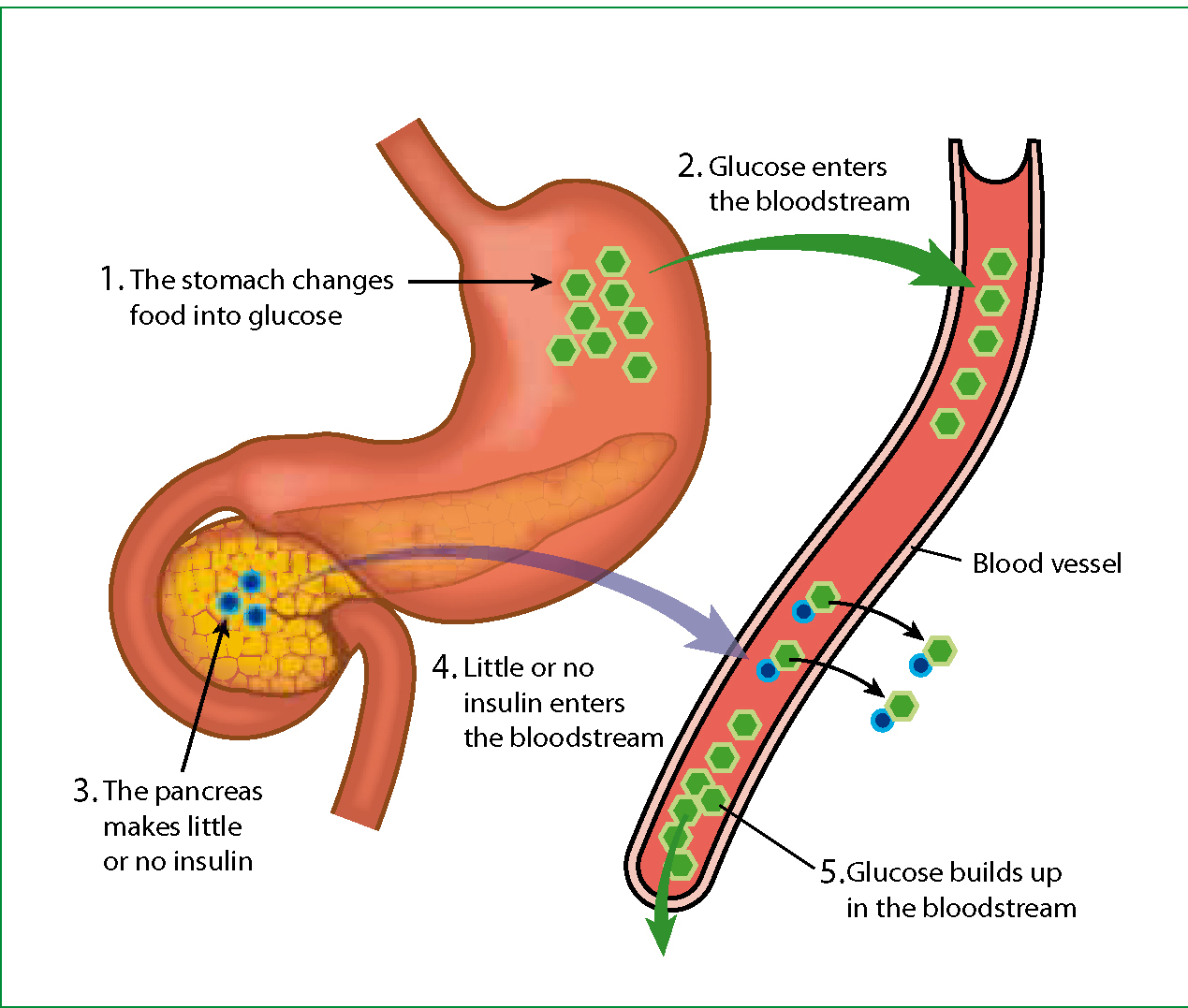

Pathogenesis

In healthy individuals, a reduction in blood glucose levels results in a series of protective counter regulatory hormonal responses. The first defence is inhibition of insulin secretion from pancreatic P-cells and stimulation of glucagon. Glucagon stimulates glycogenolysis—the conversion and release of glycogen in the liver into glucose.

Hypoglycaemia also stimulates the autonomic nervous system, causing the release of adrenaline which enhances hepatic glycogenolysis and gluconeogenesis. Adrenaline release manifests as adrenergic symptoms, including: tachycardia, diaphoresis, anxiety and tremor, warning the patient of pre-eminent danger.

However, in patients with diabetes, there are often defective protection mechanisms against hypoglycaemia. There is a defective glucagon response, thought to be due to pancreatic insulin deficiency. There is also a reduced adrenaline response due to the downward shift in the threshold glucose concentration needed to elicit a response, secondary to previous episodes of hypoglycaemia (Cryer, 2004).

As such, cautious insulin administration is paramount in the complex management of glycaemic control. In addition, alcohol potentiates inhibition of gluconeogenesis, enhances the effect of exogenous insulin, and worsens hypoglycaemia.

Clinical features

The manifestations of hypoglycaemia are often vague and non-specific (Table 1), which is why it should form part of the initial assessment of any patient. There is considerable variation in the definition of hypoglycaemia. Symptoms of hypoglycaemia and the counter regulatory effects occur at blood glucose levels of 3.6-3.9 mmol/L in non-diabetic patients (Schwartz et al, 1987; Cryer, 2001). As such, a threshold of ≤3.9 mmol/L in a diabetic population has been suggested (American Diabetes Association (ADA), 2005).

| Adrenergic | Neuroglycopenic |

|---|---|

| Sweating | Confusion |

| Palpitations | Drowsiness |

| Tremor | Lack of coordination |

| Hunger | Difficulty with speech |

| Anxiety | Blurred vision |

| Behavioural changes | |

| Convulsions/coma. |

The signs and symptoms can be grouped into adrenergic and neuroglycopenic symptoms. Adrenergic symptoms typically occur at a blood glucose level of 3.6-3.9 mmol/L (Cryer, 2008), and are due to the release of adrenaline and stimulation of the autonomic nervous system. These usually alert the patient to administer exogenous glucose.

Neuroglycopenic symptoms are secondary to neuronal deprivation of glucose and occur at blood glucose levels of less than 2.8 mmol/L (Cryer, 2008). There may be variation in the pattern of symptoms experienced, but usually there are little individual differences during each episode.

Recurrent episodes of hypoglycaemia result in hypoglycaemia unawareness. A loss of the early warning signs is due to a blunted autonomic (sympathetic) response, also known as hypoglycaemia associated autonomic failure (HAAF). Other causes of HAAF include preceding exercise or sleep, both of which attenuate the adrenergic response to hypoglycaemia. As such, patients will be unable to counteract hypoglycaemic progression by exogenous administration of glucose.

Causes

Hypoglycaemia can occur in both diabetic and non-diabetic patients. In diabetes mellitus, hypoglycaemia is either due to raised insulin concentration or enhanced insulin effect. Raised insulin concentration may be explained by accidental or deliberate insulin or sulphonylurea overdose, increased insulin absorption due to lipohypertrophy or exercise, or imbalance between insulin dose and patient's carbohydrate intake or lifestyle.

Weight loss, exercise, vomiting and breast feeding all contribute to enhanced insulin effect and signify the need to adjust insulin dosage. In non-diabetic patients, hypoglycaemia can be secondary to anorexia nervosa, liver failure, chronic renal failure, and drugs, such as quinolones. In the tropics and in returning travelers, malaria must be considered. It is also important to consider insulin or oral hypoglycaemic medication overdose in those who do not have diabetes but may have access to the medicines (e.g. one whose relative has diabetes and keeps a supply of insulin).

Management

As with any acute patient encounter, an assessment of the patient's airway, breathing, circulation and disability is paramount. Capillary glucose measurement should be taken and treatment instigated if the level is less than 4.0 mmol/L.

Management depends on the level of consciousness of the patient. If the patient is conscious and cooperative, one should administer a rapid acting carbohydrate, such as glucose gel, to quickly increase blood glucose levels, and a complex long-acting carbohydrate to maintain glucose levels (Table 2) (NHS Diabetes, 2010). Subsequently, the capillary blood glucose level should be checked every 10-15 minutes and oral administration of glucose should continue until blood glucose levels are 5.0 mmol/L or above. The patient should be observed until full recovery is achieved.

|

Rapid acting carbohydrates:

|

|

Complex carbohydrates:

|

Caution should be taken in patients taking oral hypogylcaemic agents (such as sulphonylureas), as they may have a rebound hypogylcaemic episode within 24 hours. These patients benefit from attendance to hospital. In conscious patients with hypoglycaemia, it is necessary to question directly about drug overdose. In confirmed cases of overdose with hypoglycaemic agents, it is important to establish the extent of the overdose, either by questioning, or by examination of medication packaging. This information helps with risk stratifying the patient. Furthermore, these patients will require hospitalization. Inhospital management may include incision and drainage/excision of the injection site, dextrose infusion, and close monitoring for hypokalaemia.

There have not been any truly randomized double blind controlled trials into efficacy of IV glucose vs subcutaneous glucagon. In the quasi-randomized trials available, there is evidence that patients treated with glucose recover cognitive function and normoglycaemia more quickly than those in the glucagon arm. Importantly, these trials do not all take into account the time taken to achieve intravenous cannulation, and they tend to be small trials (Howell and Guly, 1997; Carstens and Sprehn, 1998). IV 10% glucose should be administered slowly.

Clinical efficacy should be assessed with repeat capillary glucose level after 10 minutes and ongoing assessment of level of consciousness. IV glucose is an irritant, so care should be taken to ensure the cannula is properly inserted and patent, to avoid extravasation and thrombophlebitis. If IV access is delayed, 1 mg intramuscular (IM) glucagon can be used.

Glucagon mobilizes glucose from the liver and is less efficacious in malnourished patients (e.g. alcohol abusers, patients with eating disorders, and some elderly patients), prolonged starvation or those with liver disease. A more recent study compared outcomes of subcutaneous glucagon and oral glucose. It showed that those treated with subcutaneous glucagon had a significantly greater increase in mean capillary glucose, a greater improvement in their Glasgow coma score, and required fewer repeat doses when compared with oral glucose (Vermeulen et al, 2003).

Collateral history is of vital importance when the patient has decreased conscious level secondary to hypoglycaemia. If it is not clear that the patient has taken an overdose, or indeed does not have diabetes mellitus, it is good practice to question further to ascertain if anyone else in the house has diabetes.

Once the patient has regained consciousness, and a safe swallow is established, patients should be given complex carbohydrates to maintain normal glycaemic levels. With patients who are at high risk of aspiration and in the absence of glucagon, glucose gel can be administered by soaking a piece of gauze swab and placing it in between a patients lip and gum to aid absorption (Joint Royal Colleges Liasion Committee (JRCALC), 2006).

After the acute management, there are no clear guidelines on the need for subsequent admission to hospital. A recent study suggests that patients who require admission include children, the elderly, and patients who are persistently symptomatic despite initial therapy (Brackenridge et al, 2006). In addition, prolonged hypoglycaemia can be anticipated in patients on long-acting insulin (as in the case above), or sulphonylurea treatment. These patients may require a prolonged infusion of dextrose to maintain blood glucose levels. 2-7% of patients are at risk of repeat hypoglycaemic event within 48 hours (Fitzpatrick and Duncan, 2009).

‘After the acute management, there are no clear guidelines on the need for subsequent admission to hospital’

Alongside the medical treatment of patients admitted following insulin or oral hypoglycaemic agent overdose, a psychiatric assessment is key. In fact, inpatient mental health review in these patients is mandatory before discharge. The majority of cases are deemed to be ‘low risk’ (i.e. safe for discharge from hospital from a psychiatry viewpoint), and are discharged with an appointment for further review by mental health services in the community.

Conclusions

Hypoglycemia remains to be a common, easily reversible but potentially deadly complication in patients with diabetes. Most often, it is secondary to an unintentional mismatch in insulin dosage and metabolic requirements of the body. However, one should be alert to the possibilities of self-harm or induced harm, particularly in cases involving children or vulnerable adults. Although the large majority of patients achieve full recovery, a proportion suffers long-term neurological sequelae or death.