Out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA) is the archetypal emergency. Ambulance trusts take a great deal of effort to lessen the morbidity and mortality resulting from OHCA. While nobody could suggest that there is anything wrong with this, it is often forgotten that patients’ friends, family and loved ones are present at many of these emergencies.

Witnessing the resuscitation of a loved one is undoubtedly a traumatic event, and this literature review was carried out to establish current research surrounding the long-term effects of seeing this, assess the quality of this research, highlight areas for further research and make suggestions for UK paramedic practice.

The scope of this literature review will be limited to inspecting the relationship between witnessing resuscitation and the later development of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or closely related symptoms. Given the nature of human psychology, there is much that could be written as to what constitutes PTSD, but this falls outside of the scope of this review.

There is much professional comment on whether emotionally involved loved ones witnessing resuscitation has a negative impact on the quality of care, and this is touched upon briefly as it relates to the research question. Nonetheless, this is an important area of research. Clinicians may be tempted to exclude loved ones from the scene during resuscitation for this reason, but further studies are needed in this area, and the research that exists does not seem to immediately favour such a decision.

Paramedics are the primary responders to OHCA in the UK, and are usually the senior clinical resource. As such, they take responsibility for what is occurring as care is delivered.

What is the responsibility of the paramedic with respect to the family members and emotionally involved onlookers at these events? What is the best approach to managing their presence from both clinical and emotional wellbeing perspectives when resuscitation is required? Some of these issues will be discussed as they flow out of the review of the available literature.

Methodology

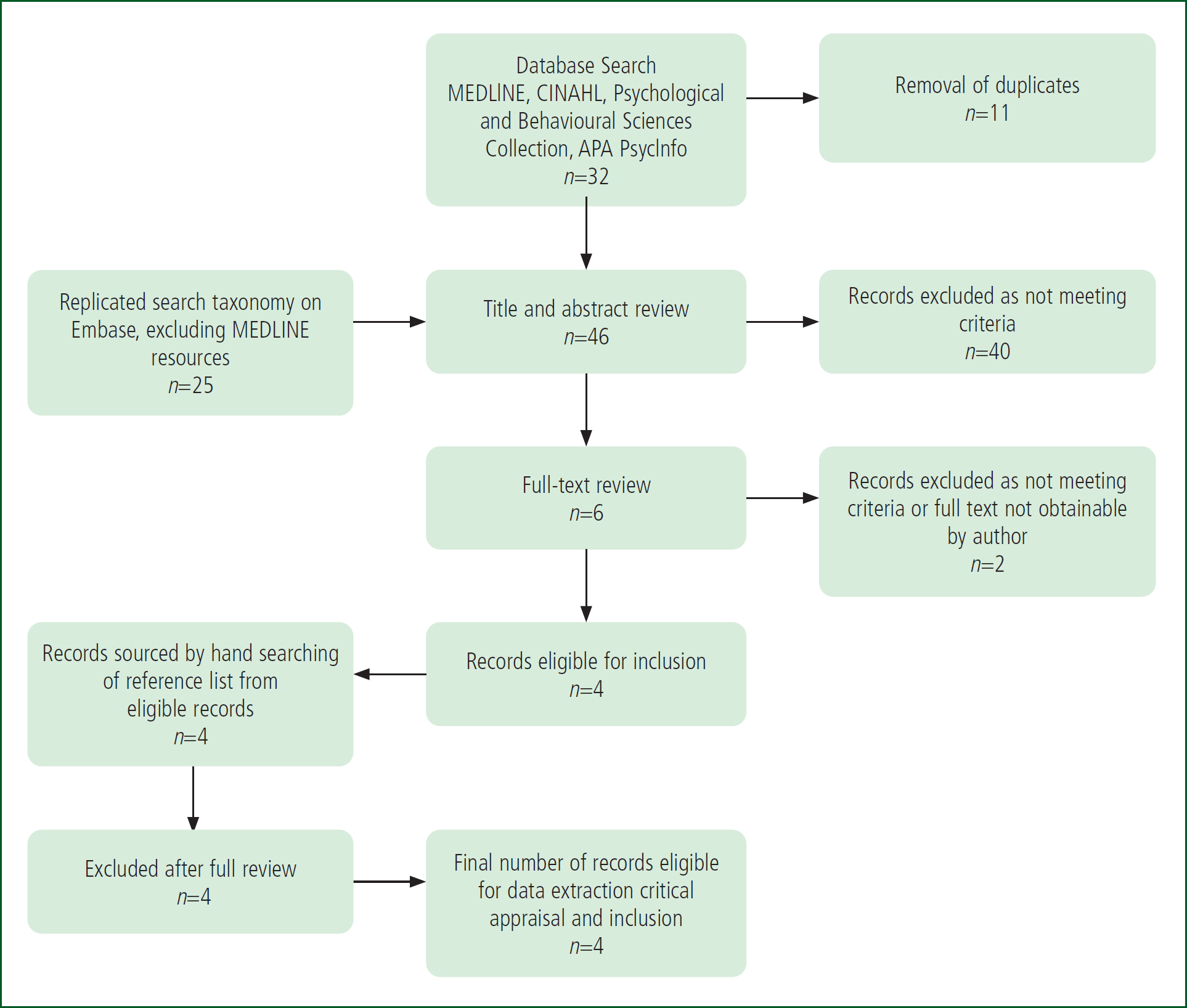

Using the EBSCOhost service, a search was conducted using the MEDLINE, CINAHL, the Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection and the APA PsycInfo databases. A further search was conducted on Embase, which excluded articles also found on MEDLINE. It was deemed that searching both medical and more psychological databases carried the greatest potential for uncovering the largest number of studies relevant to the review.

The search term taxonomy employed was: Witnessed (OR Observed OR Present) AND Resuscitation AND PTSD. Expanders for related words and equivalent subjects were used and searches were conducted using Boolean/phrase modes to account for the variety of terms used to describe both the resuscitation event and PTSD.

Following the conduction of database searches and screening, the reference lists of eligible records were hand searched and additional papers screened for inclusion. Reference lists of current ethical guidelines in resuscitative practice from the Resuscitation Council UK and the European Resuscitation Council were also hand searched, but these yielded no additional records.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were designed to capture studies and experiments relevant to the question. This is an area in which primary research is limited, and capturing the available evidence as opposed to discursive articles was paramount. Anecdotal evidence, case studies, professional comment and study material were therefore excluded.

Furthermore, it is recognised that conducting a study in this area has ethical dilemmas; is it justifiable to expose participants to resuscitation on purpose, when it might cause them lasting psychological harm? How can this be navigated in study design? As such, no particular study types were excluded where a target population was present and it met the eligibility criteria.

Studies published before 2010 were excluded, as it was desired to assess the current state of research. It is acknowledged that the research around family-witnessed resuscitation extends back to at least 1987 (Doyle et al, 1987), and the discussion itself likely much further. The purpose of this literature review is not to provide commentary on the entire clinical discussion to date but to evaluate the contemporary evidence base and its relevance to UK paramedic practice.

Studies not assessing PTSD or closely related mental health effects of witnessing resuscitation were excluded. Anecdotal views of professionals were also excluded because of the absence of quantifiable data from which conclusions could be drawn. Studies not examining the impact of witnessed resuscitation on family members or close equivalents were also excluded.

Studies that took place in hospital were not excluded, given that earlier evidence and parts of contemporary evidence take place in emergency departments and examine the target population. However, this review makes its recommendations in the context of paramedic practice as it is the closing assignment of an undergraduate degree in paramedic science at a UK higher education institution.

The precise criteria can be formulated as PICOS: population: family, friends or loved ones of patients receiving resuscitation following cardiac arrest; intervention: witnessing resuscitation; comparison: not witnessing resuscitation; outcome: development of PTSD or related mental health conditions; and study: focused on the population by any method (Table 1). A flow chart was created to demonstrate the search and eligibility processes and is displayed below (Figure 1). A data extraction form was designed to capture comparable and relevant information across the study types.

| Included | Excluded | |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Family, friends or loved ones of patients receiving resuscitation following cardiac arrest | Any other population |

| Intervention | Witnessing resuscitation | Other interventions (e.g. remote ‘breaking of bad news’) |

| Comparison | Not witnessing resuscitation | Any other comparator |

| Outcome | Development of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) or related mental health conditions | PTSD or other mental health effects not measured/considered |

| Study | Focused on the population by any method | Anecdotal views of professionals, or otherwise not focused on a population |

Given that two study types have been included for review, they were critically appraised using the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (2023) checklist relevant to the study type. This allowed for critical appraisal following data extraction with some underlying methodological unity.

Results

Four articles were included for review. Although four further articles were identified from hand-searching of these records, they did not meet the inclusion criteria because of their publication date or because they did not address family presence during resuscitation directly but PTSD and grief more generally (Suzuki et al, 2020). One article was not obtainable as full text and was excluded. Another was excluded because it did not meet the PICOS criteria following full-text review, as the control condition was not a population that did not witness resuscitation but those who witnessed resuscitation without a specific support protocol (Soleimanpour et al, 2017). While this paper is an important part of the discussion about how practice could be changed, it does not meet the inclusion criteria of this review.

Study 1. Jabre et al (2013)

‘Family presence during cardiopulmonary resuscitation’ is the strongest piece of available evidence in favour of the intervention. Conducted in France, this paper reports a multicentre randomised controlled trial (RCT) conducted in the prehospital environment. It is well designed, specific to the research question of this literature review and has statistically significant results from an appropriately powered sample size.

Participants provided deferred consent at the time of the incident, and were followed up for assessment of PTSD, anxiety and depressive symptoms at 90 days via a structured telephone interview by a trained psychologist blinded to the study group of the participant.

As secondary outcomes, the authors assessed stress levels in the medical teams in both study groups as well as correlations between the intervention and the clinical outcome of the patient.

It found that there were ‘significantly higher’ levels of PTSD-related symptoms in family members who did not witness resuscitation 90 days after the event (adjusted OR 1.6; 95% CI (1.1–2.5); P=0.02).

The control group—who were not routinely offered the opportunity to witness resuscitation, and of whom only 43% did compared to 79% in the intervention group—also had a higher proportion of participants unable to complete the telephone interview because of emotional distress, and this was statistically significant (P=0.007).

Attractive as the results of this study are in providing a direct answer to the research question of this review, several cautions emerged following data extraction and critical appraisal. First, the population studied was largely homogenous in terms of ethnicity, as you would expect in a study limited to one country. There is characteristic data of the participants that includes their self-selected religion, but no structured exploration of their views of death. It also studies only adult resuscitations witnessed by adults.

Importantly, 15% of patients who were resuscitated were categorised as ‘expected deaths’ —no explanation of what this means is offered, nor why resuscitation was performed in these circumstances. Granted, the proportions were similar in the intervention and the control groups, but, of the overall total, this a large enough number that more information is needed to determine if this affects the validity of the results. This is not acknowledged as a limitation in the article, nor can we be sure that the data were adjusted to take this into account.

It is also unclear if the study participants were effectively blinded to the parameters of the study. If the consent process involved a description of the intervention-control parameters, then the participants were not blinded at the time of giving consent and before they were assessed for the primary outcome. If, however, the consent process contained only an outline of the study aims (to examine the relationship between witnessing resuscitation and PTSD in family members), then the participants were likely blinded to their study-group allocation until publication. They were certainly blinded at the moment they were or were not offered the opportunity to witness the resuscitation. This runs the risk of corrupting the findings as it introduces an element of selfselection at the point of giving consent. No data are provided on the number of candidates who refused to participate.

Importantly, not all patients who were resuscitated in this study died. The authors acknowledge that, although their modelling suggested that this was not significant when they excluded relatives of surviving patients, it was nevertheless a significant factor in psychological outcomes and deserves more detailed treatment in future research. It seems rational that a larger trial examining bereavement versus survival as a key factor in the development of ongoing psychological symptoms of depression or PTSD would find an association, but this is yet to be attempted so cannot be stated categorically.

In the context of the current state of research, this study is nevertheless a key and central part of the current direction of the conversation with regards to family presence during resuscitation. It is further corroborated by its research team, who followed up with the same participants in a later paper (Jabre et al, 2014; study 3).

Study 2. Compton et al (2011)

Conducted in the US, this study, entitled ‘Family-witnessed resuscitation: bereavement outcomes in an urban environment’ analysed the association between witnessing resuscitation and bereavement outcomes such as PTSD and depression in a cohort of 65 participants in a prospective comparison study conducted at two hospitals.

It found an association between bereavement and poor psychological outcomes, but did not support the idea that witnessing or not witnessing resuscitation impacted the severity of these outcomes, standing therefore in contradistinction to Jabre et al (2013).

There are, however, several serious methodological limitations in the study design that hinder the generalisability and validity of the results. Primarily and most obviously, the sample size was only 65 participants, 75% of whom were African Americans. The high level of ethnic uniformity within an already small sample size immediately prevents any rapid cross-application of the findings to other settings. The authors acknowledged this, along with a complete lack of randomisation, blinding or longer term follow-up.

They also acknowledged that there was a high degree of selection bias regarding which family members were included in the intervention group. Participants were selected by nurse practitioners who were trained to ‘watch the family member’s behaviour in the waiting room to determine if he or she is an appropriate candidate (i.e. relatively calm without exhibition of aggressive actions or excessive display of emotions) for an invitation to witness the resuscitation’.

The authors excuse this by stating that this type of bias would be present in all similar settings, but this does not account for the inability to do this in OHCA. It also works upon the assumption that the present model of excluding automatically and inviting select candidates in secondary care is essentially correct; this type of selection bias would be eliminated if practice were changed and it became the norm for relatives and close loved ones to always be present at resuscitation in the emergency department in the absence of a clear reason to exclude them (e.g. excessive distress or for the safety of clinical staff, although there is little evidence from this review that staff are at any additional risk of distraction, harm or medico-legal complications from permitting family members to witness resuscitation).

Furthermore, physicians in charge of resuscitation attempts had an automatic right of veto on a case-by-case basis, without having to meet any criteria or explain their decision. Respectful as this is to practitioners, it does confound the results of the study and this is not acknowledged. No data are provided on the number of times physicians prohibited the entrance of a family member, their reasons or the psychological outcomes of those individuals. Without these data, a further selection bias in the recruitment process cannot be ignored.

These significant limitations prevent the generalisability of the findings, and even call the validity of the study design into question.

Despite this, the paper stands as evidence that there is at least an association between bereavement and the development of depression and/or PTSD at 30 and 60-day intervals. This is an important underlying assumption for other later research, and likely spurred the creation of the more considered studies that followed it.

However, it does not, in the end, contribute to answering the research question of this review directly because of failures in the study design, and its results do not correlate with the larger and more robust trials in this area.

Study 3. Jabre et al (2014)

Although not a separate experiment, this paper is a longer-term follow-up of participants from the Jabre et al (2013) study, now known as the PRESENCE trial.

It has been assessed as a separate record because the team used different assessment criteria for PTSD when they followed up with participants 1 year after the event, with the addition of both an inventory of complicated grief (ICG) score, and a diagnostic tool for a major depressive episode, the MINI assessment (Sheehan et al, 1997). Fresh statistical analysis of these results was performed, resulting in the presentation of a new data set, further justifying the assessment of this paper separately from the earlier study.

In this follow-up of the earlier trial, 408 (72%) of the originally enrolled participants were assessed for symptoms of PTSD and depression one year after the resuscitation of their loved ones. A similar number of participants were lost to follow-up in the control and intervention arms.

The study found that participants in the control group and who had not been offered the opportunity to witness resuscitation by the physician had PTSD-related symptoms at 1 year significantly more frequently than the intervention group and those who had been invited to witness resuscitation by the physician (95% CI (1.1–3.0) and 95% CI (1.1–2.0) respectively, P=0.02).

The findings of this additional analysis of the participants at 1 year provides the longest term follow-up data currently available in the literature. That a psychological benefit was still being experienced by those in the intervention arm of the study at this chronological distance from the resuscitation they witnessed is an important finding. It lends serious weight to the suggestion that family members and loved ones should be offered the opportunity to witness the resuscitation of patients in cardiac arrest in prehospital settings resembling those in France, with similar clinical interventions by EMS providers, aetiologies of cardiac arrest and ethnolinguistic cultural norms.

This indicates that the problems detected in the original study design in terms of its generalisability are not confounded by the length of the follow-up in this additional analysis.

Multivariate analysis of a multifactorial problem among a broader range of participant populations, with interviewing on advanced characteristics that include beliefs about death is still required to move towards certainty that this intervention could benefit all or certainly most emotionally involved onlookers during the resuscitation of their loved one.

Study 4. Erogul et al (2020)

Conducted in the US, this study, entitled ‘Post-traumatic stress disorder in family-witnessed resuscitation of emergency department patients’, is a cohort study of a prospective, cross-sectional nature. Family members of patients who were geographically triaged within an emergency department to a ‘critical care room’ were recruited after interrogation of the hospital electronic records, and a convenience sample of 423 participants was collected at an average of 1 month after the exposure via telephone interview.

The study found that participants who had witnessed resuscitation had significantly higher mean Impact of Events Scale–Revised (IES–R) scores than those who did not, which places its findings in contradiction of those of the Jabre et al (2013) study.

Appropriate statistical analysis was undertaken but, as with other cohort studies taking single-point, cross-sectional approaches, some elements of the study design impacted the generalisability of the data, including that participants were followed up only 30 days after the event itself.

Significantly, the definition of resuscitation in this study was explicitly broader than cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). The authors determined resuscitation to have taken place by the patient having been geographically triaged to a critical care room in which loved ones were also present, and the convenience sample obtained at 1 month was composed of participants who self-selected as having witnessed or not witnessed resuscitation. Leaving this definition so broad is not without arguments in its favour but it effectively leaves a central component of the study design up to the opinion of a non-medical participant who has self-selected whether they belong to the intervention or control arm. This creates difficulty in knowing exactly what it was that each participant witnessed, and how this then compares with other studies that examine resuscitation and its impact on psychological wellbeing in similar cohorts following CPR carried out after cardiac arrest.

For this reason, the findings of this study cannot truly be viewed as a contribution to the conversation in which this review is interested. That said, some of its participants did witness CPR, but this number is not separated out for analysis in the data, nor is it modelled for in the interpretation of the results. This might be viewed as a strength if the intention is to start a related but separate conversation around family experiences of witnessing critical care in general but is not specific to the topic of this review.

Discussion

To attempt to provide a summary, the data in this review show that the cardiac arrest of a loved one can and does produce symptoms of PTSD, depression and anxiety in family members and close relatives of the patient.

There may be some variance in the rates of occurrence and the severity of these symptoms between ethnicities, geographies and the setting in which the cardiac arrest and subsequent resuscitation attempt occurs.

The best available evidence at present suggests that the long-term effects of witnessing resuscitation for emotionally involved onlookers are a beneficial reduction in the incidence and severity of PTSD and related symptoms; further research is needed to clarify and explore other variables that may impact this in complex ways not yet fully accounted for in the study design of the presently available evidence.

A protocol is in place for a full systematic Cochrane review of this topic and is believed to be under way (Afzali Rubin et al, 2020). The scope of that forthcoming review uses the same databases for interrogation as this review but without the year of publication restriction.

An earlier systematic review assessed only RCTs in this area, not cohort studies (Oczkowski et al, 2015), and did not account for several significant issues that may affect results, such as ethnography, religious beliefs about death and specific interventions received or not received. It is not considered, for these reasons, to be broad enough to provide an answer to this question or to inform practice. The study was also more focused upon patient-centred outcomes from the resuscitation than on psychological effects on family members, which were secondary outcomes. A formal meta-analysis of the data from relevant trials could be beneficial, but would not significantly improve the condition of the present body of evidence without further research of additional factors involved in the development of PTSD following the resuscitation of a loved one.

The studies reviewed reflect the most recent research in this area but both their data and design show this is a complex issue to research effectively. The Jabre et al (2013) study is the strongest piece of evidence to date but is still of itself not fully generalisable so cannot support an immediate change in practice.

Although touched upon in the studies presented herein, there has yet to be a study in this area that includes detailed analysis of participants’ religious and metaphysical opinions about death as part of the study design. This would be difficult to achieve in a way that allows effective comparison, but is nevertheless a crucial factor in how the types of populations these studies interact with view what is occurring. The Jabre et al (2013) study included a characteristic of religion but this does not necessarily equate to a specific set of beliefs about death and dying at an individual level. These factors are likely to have a profound influence upon the grieving process, and therefore play a role in the development of complicated grief or PTSD.

Paramedics working in prehospital settings in the UK deal with OHCA patients from a variety of ethnic, religio-cultural backgrounds, and should consider asking patients’ families if there is anything specifically they would like to do during the process of resuscitation (such as praying or touching the body) as long as this does not interfere with the delivery of effective care.

For the purposes of this literature review, resuscitation has been considered to be CPR akin to the advanced life support administered by paramedics in the UK, which broadly falls in line with the Resuscitation Council UK’s (RCUK) (2021a) guidelines. This follows the trend in the literature, which is increasingly adopting this definition of resuscitation.

Study 4 however—Erogul et al (2020)—brought to the author’s attention the broader definition of resuscitation that exists in healthcare, which may not always include CPR. Paramedics would be wise to consider in practice that family members may be equally traumatised or helped by witnessing other aspects of prehospital critical care; this merits investigation but should be discussed and researched elsewhere rather than in this review.

The most recent editions of resuscitation guidelines from the Resuscitation Council UK and the European Resuscitation Council state that family members and other individuals closely related to the patient should be offered the opportunity (but not necessarily encouraged) to witness resuscitative efforts, with the caveat that a member of the team can provide support to them during this experience. This is likely more applicable in secondary care where resuscitation teams may be larger and more readily added to than in the prehospital environment.

In the prehospital setting, an additional and sufficiently experienced member of staff who can provide this support to emotionally involved onlookers during resuscitation may not always be available. In line with this, guidelines state that clinicians should be equipped through training to support family members and emotionally involved onlookers during resuscitation. (Mentzelopoulos et al, 2021; RCUK, 2021). Paramedics in ambulance services potentially stand to benefit from this being drawn to their attention so that they do not unintentionally prohibit or discourage family members and loved ones of patients already present during an OHCA to leave the scene of a resuscitation if they wish to remain and can be safely accommodated. In the Jabre et al (2013) study, many family members who witnessed resuscitation expressed and sent letters of thanks.

A secondary aim in many studies (including those reviewed here) has been to examine the effect of family presence on the quality of care delivered and the wellbeing of the staff clinically involved in the resuscitation. While this falls outside of the scope of this review, there is no persuasive evidence in any of the studies nor in the wider context of the literature on this topic that allowing loved ones to witness resuscitation in any way increases the risk of clinical error, poor clinical outcomes, interference by family members in the course of treatment, or medico-legal proceedings (Jabre et al, 2013).

Limitations

This review was conducted at the conclusion of a UK paramedic undergraduate degree by a sole author, which inevitably runs the risk of bias in the review design, inclusion and exclusion criteria and critical appraisal process. It is acknowledged that this places a significant limitation on the quality and general usefulness of this paper.

Earlier data that fall outside the inclusion criteria may have some relevance but did not meet the study design of this review. Rather than move the boundaries of the inclusion criteria, it was felt that the state of current research should be assessed as it very much builds upon the findings and data of earlier work. This does, however, create a potential limitation to this review.

The use of PICOS criteria to include and exclude records was useful in determining that records with population data were assessed in this review, but this is not to say that clinical case studies, anecdotal evidence, simulation studies and professional opinion have no merit in this discussion or relevance to the research question. Excluding studies of this type also placed another limitation on the scope and usefulness of this review.

Conclusion

Following this review, the conclusion from the data at hand is that, at present, the best available evidence (which is of moderate quality) suggests that offering family members and loved ones of patients experiencing an OHCA the opportunity to witness resuscitation is unlikely to cause any harm, and may offer long-term psychological benefits in relation to symptoms of PTSD and depression following the event.

In addition, allowing relatives to witness resuscitation is not associated with worse clinical outcomes for patients, increased rates of clinical error or medico-legal accusations of malpractice.

There may be some variation in the rate and severity of PTSD symptoms in families and loved ones of OHCA patients, irrespective of whether they witness resuscitation, in different geographies and ethnic groups. This requires further and more detailed research.

Recommendations

Many more studies addressing multiple factors involved in the development of PTSD following witnessing or not witnessing resuscitation are required to build evidence that offering and/or encouraging family presence during these events is beneficial psychologically.

Key areas for analysis include the impact of beliefs about death from a religio-cultural perspective on the development of PTSD symptoms, as well as broader and more varied ethnic and geographic studies.

Conducting research regarding the effect of witnessing particular interventions may also have some benefit—it is rational to suggest mechanical chest compressions and artificial ventilation may be more distressing to witnesses than their manual counterparts, but there is no research at present to provide insight in this area. The same could be said of many other critical care interventions in both intra- and peri-cardiac arrest.

A final suggestion might be the consideration of even longer-term follow-up. PTSD is a multifaceted condition, and patients who develop complex PTSD may experience some symptoms indefinitely; whether this occurs may depend upon the nature of the trauma and the context of the rest of their experiences (Hyland et al, 2017).

Implications for practice

In line with the most up-to-date resuscitation guidelines and the data discussed above, paramedics should be prepared to offer family members and close loved ones of patients in cardiac arrest the opportunity to witness resuscitation. At the very least, they should not discourage or prohibit it.

As evidence builds, it may be appropriate for undergraduate and CPD paramedic training to include elements of supportive care for loved ones at the scene of a resuscitation.