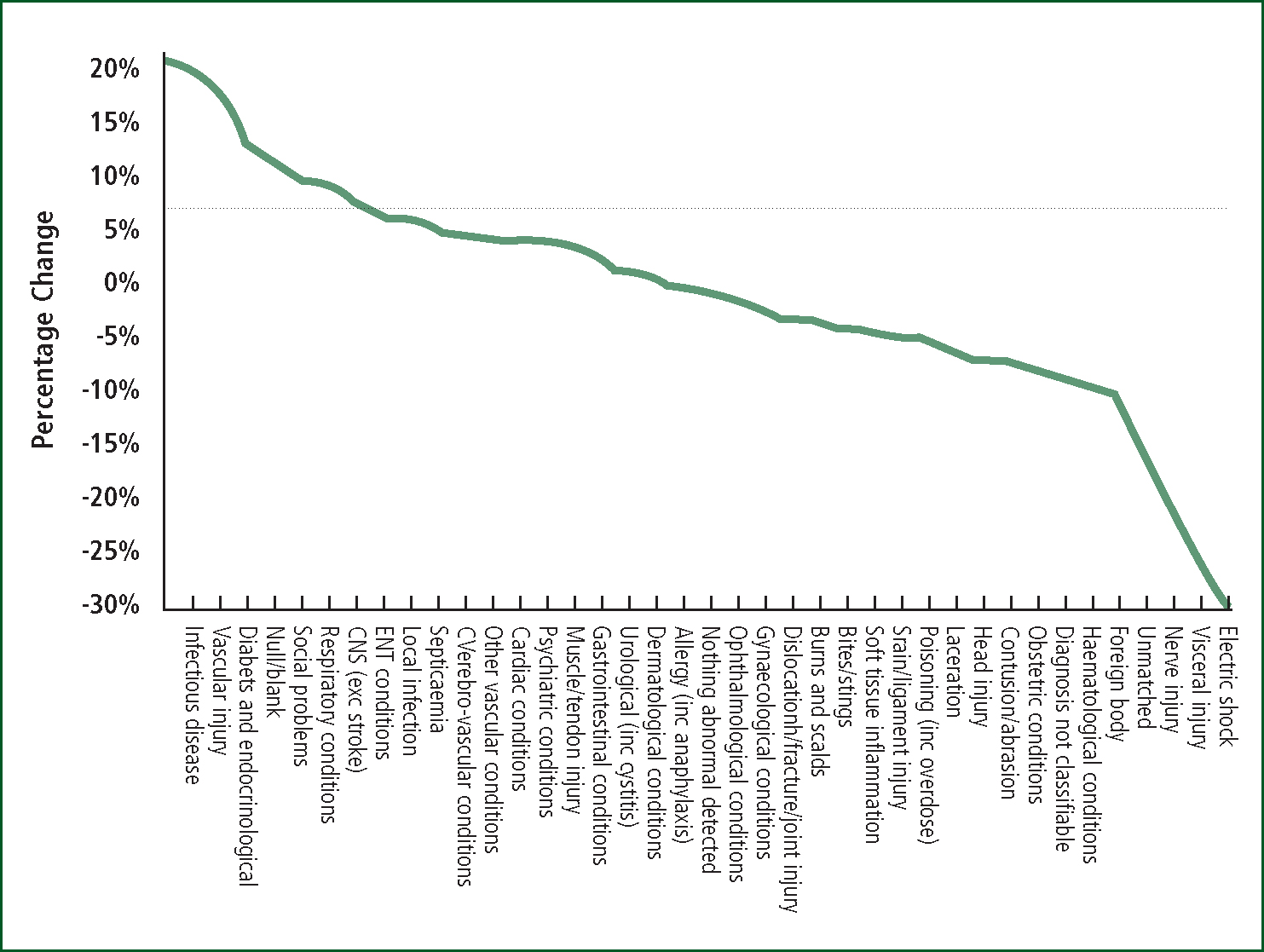

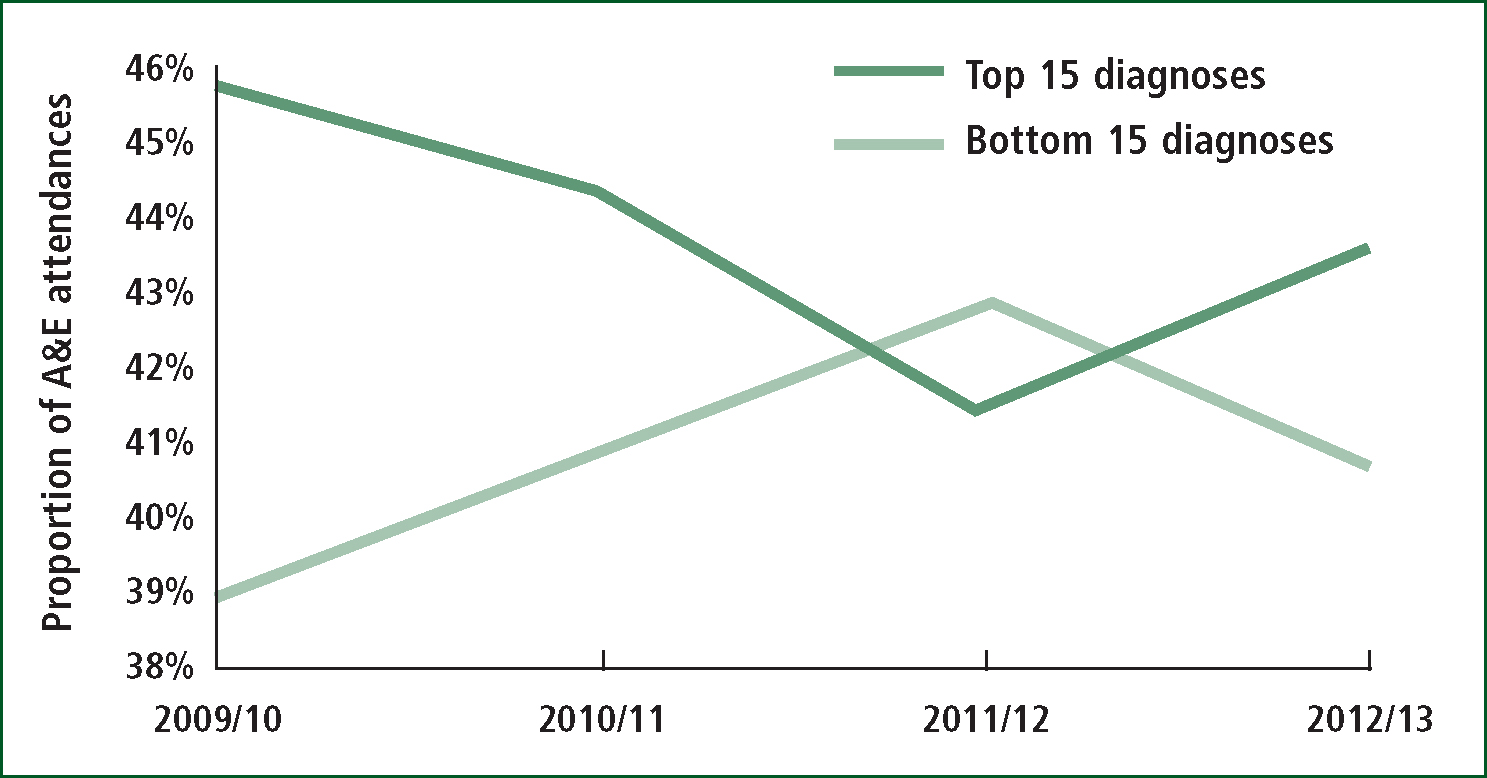

The capacity problems in A&E are now widely recognised, with shortages in A&E staffing, ready access to a GP or even the ageing population widely blamed (Jones, 2013c–h). However, Figures 1 and 2 reveal the consequences of an event in early 2012, which also led to increased deaths and medical admissions (Jones, 2013a–e), and marks the point of a sudden and unexpected shift in the case mix arriving at A&E. On the x-axis of Figure 1 are a series of more serious medical conditions (highly likely to require ambulance transport and result in an admission), which substantially increased their share of the arriving case mix with associated reductions in the proportion of less serious ambulatory and minor injury type conditions. Hence, there was a step-like increase in admissions to A&E seen to occur around February of 2012 (Jones, 2013b), and the abrupt nature of this shift is illustrated in Figure 2, where continuous trends prior to 2012/13 are suddenly interrupted.

More revealing is the fact that the increase in these serious medical conditions coincides with an unexplained single-year-of-age and condition-specific increase in deaths and medical admissions across England and Wales (Jones, 2013b; 2013l; 2014c; 2014f). This increase in deaths showed spatial spread and was a continuation of an earlier initiation and spatial spread throughout Scotland during 2011 (Jones, 2013l). These events have occurred before at roughly five year intervals and involve synchronous increases in emergency medical admissions, A&E attendance, GP referral and changes in the gender ratio at birth (Jones, 2013a; 2013f; 2013k). It is of interest to note that following a similar event in 1993 the use of ambulance services in Wiltshire showed evidence for a step-like increase, which appeared to be specific to medical conditions (Wrigley et al, 2002).

While it is true that the number of persons discharged from A&E back to their GP has shown a steady increase over many years, at no time has this trend shown the step-like changes observed in medical admissions and GP referral which occur in synchrony with the increase in deaths (Jones, 2013e). The increase in deaths is likewise totally uncharacteristic in that it lasts for 18 to 24 months before reverting back to the expected time trajectory (Jones, 2013c; 2013l, 2014a; 2014e).

This unusual cluster of events has led to the proposal that we are dealing with an outbreak of a persistent infectious agent as opposed to the more usual ‘spike’ infectious events observed for influenza and other non-persistent infections (Jones, 2012; 2013a; 2013e–f; 2014a–b). The infectious hypothesis is given further weight by virtue of very high age specificity (Jones, 2014a; e–f), which arises out of a phenomena called ‘antigenic original sin’, i.e. the immune system is primed by first exposure to a particular strain of an infectious agent which creates age cohorts, leading to a single-year-of-age sawtooth pattern regarding severity of symptoms when the population is exposed to a later outbreak arising from a different strain of the same agent (Francis, 1960). Note that the group of infectious diseases showed the greatest proportional increase in Figure 1.

The next curious observation is that each of these ‘outbreaks’ appears to initiate a time-based cascade in conditions (Jones 2014a; 2014e). Conditions showing an early increase include unknown viral illness (Jones, 2014e), while emergency oncology admissions increasing around one to two years later (Jones, 2014c) and admissions for tuberculosis increasing three to four years later (Jones, 2014d).

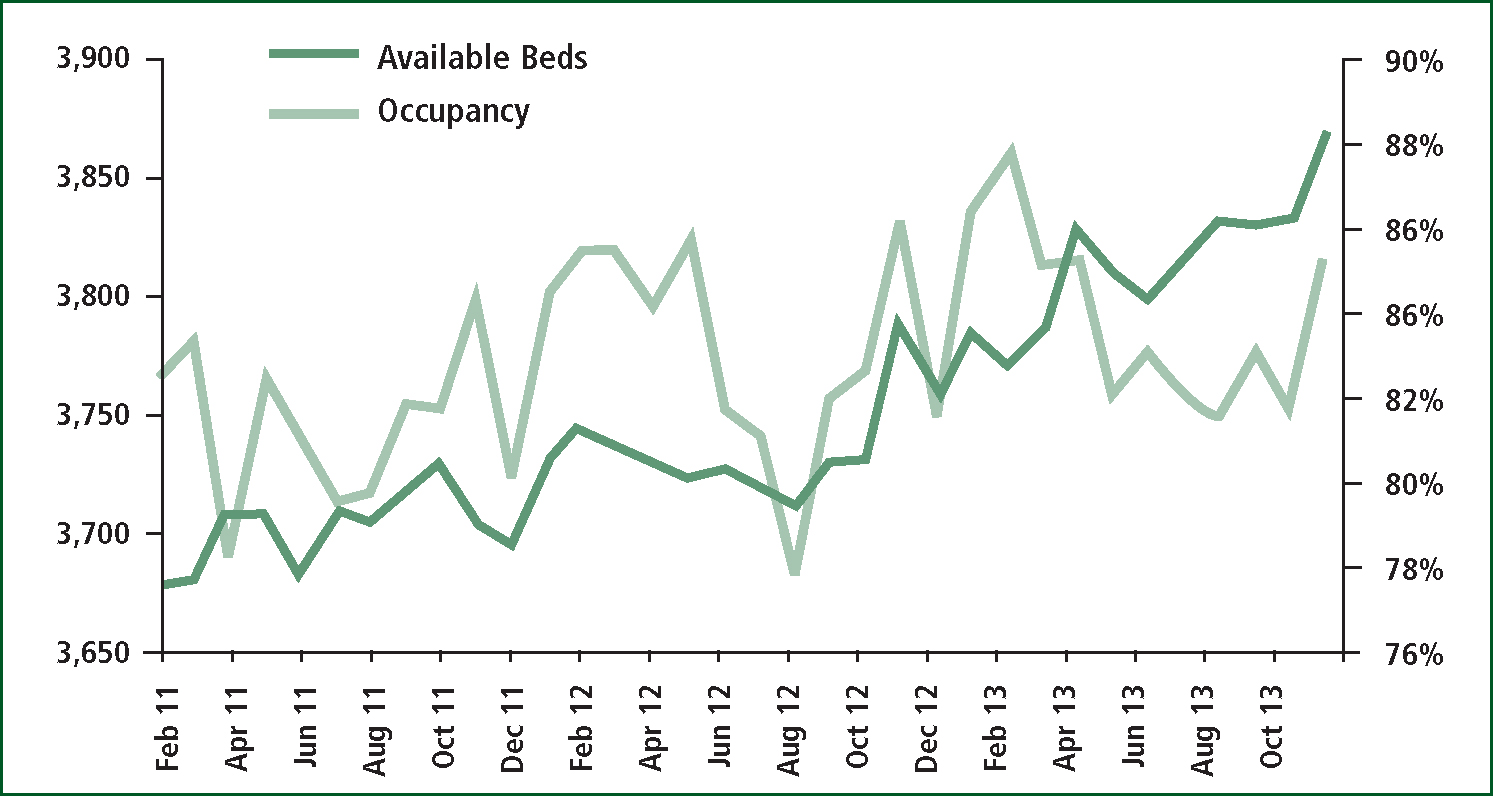

Figure 3 is of interest in that the need to expand the number of available critical care beds seems to be felt across the country by around August of 2012, and this expansion in bed numbers does not prevent ICU bed occupancy from rising still further, i.e. compare August 2013 with August 2011, etc. Clearly whatever is happening has nothing to do with trivial matters concerning GP availability or minor injury as was demonstrated in Figures 1 and 2.

Hence the concern is that while the review of emergency and urgent care led by Sir Bruce Keogh may effectively address a number of symptoms, i.e. lack of capacity in A&E and primary care, it will not address the more fundamental reason for the largely unexplained increase in a specific set of medical conditions (Jones, 2013a; 2013h), which seems to be the fundamental exacerbating factor leading to the apparent lack of capacity.

The implications to paramedics and the ambulance services should be clear in that there is a long time-series of step-like increases in serious medical conditions requiring an ambulance journey to A&E. This situation has been exacerbated by inexcusable and internationally high levels of hospital bed occupancy. High hospital bed occupancy is further increased by these events which compounds existing capacity constraints creating queues in A&E, ambulance diverts and/or queues outside of A&E (Jones, 2011a–d; 2013g). The implications to our understanding of the infectious basis for disease and disease exacerbation is likewise self-evident (Jones, 2013h).

‘The implications to paramedics and the ambulance services should be clear in that there is a long time-series of step-like increases in serious medical conditions requiring an ambulance journey to A&E’

While this should in no way be seen as an excuse to do nothing, it is merely pointing out that the required structural changes to the way in which care is delivered may only provide temporary relief. The root cause may need to be addressed via identification of the specific agent, immunisation and other public health measures.

At present, the official response appears to be one which ignores the evidence in favour of politically-correct solutions. It would seem prudent for ambulance services to re-appraise their demand data under the assumption that the small area patterns of single-year-of-age and condition specific spread in demand may be arising from the relatively slow infectious spread of a persistent agent rather than assuming simplistic notions around the ‘inability’ of various NHS services to ‘manage’ demand.