LEARNING OUTCOMES

After completing this module, the paramedic will be able to:

- l Understand the key principles and frameworks that support decision-making

- l Provide an overview of critical thinking and problem-solving

- l Reflect on Bloom's taxonomy, including tacit and explicit knowledge and how these can be used in paramedic practice

- l Consider the application of professional standards in decision-making in prehospital practice

If you would like to send feedback, please email jpp@markallengroup.com

Decision-making is an important and fascinating aspect of clinical practice. This article examines problem-solving and critical thinking and briefly reviews neuroanatomy involved in making decisions. It also considers the application of these processes in prehospital practice.

People often make poor decisions when it comes to their health behaviours. In 2021, in all 38 countries that belong to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD, 2023), heart attack, stroke and other circulatory diseases were responsible for 25% of all deaths, one in five deaths were from cancer, and COVID-19 accounted for 7% of all deaths. The global rise in obesity and associated diabetes and cancer and cardiovascular disease are linked to poor nutrition and a lack of regular exercise. Tobacco use is also associated with cancer and cardiovascular disease.

OECD (2023) data on avoidable mortality show that cardiovascular disease (including ischaemic heart disease and stroke) accounts for 37% of deaths from diseases amenable to treatment in all its member countries. The contributing factors are complex but, before the COVID-19 pandemic, slowing improvements regarding heart disease and stroke contributed to reductions in life expectancy; COVID-19 may have since contributed indirectly to higher mortality rates from circulatory diseases in some countries owing to disruptions to healthcare delivery (OECD, 2023).

There are disagreements over actual mortality rates that can be attributed to obesity, physical inactivity and smoking. All these health behaviours result from personal decision-making and are inextricably linked to disease. Despite developments in global health policy, attempts to change negative health behaviour often lie outside traditional medical care (Schroeder, 2007; Bull et al, 2020).

Schroeder (2007) posed the question of ‘obesity being the next tobacco’; both start in childhood or adolescence and disproportionately affect lower socioeconomic groups. Wven national policy decision-making can be flawed. Following the dissolution of Public Health England (PHE) and, following the pandemic, concerns were raised that health services would be put at risk due to lack of resources (Elwell-Sutton et al, 2020). Combined with a food industry that is promoted from a regulatory perspective, unlike tobacco companies, this makes helping individuals with health-related decision-making more challenging.

Many cardiovascular events are preventable through pharmacological interventions and lifestyle behaviour changes. Thomas et al (2020) concluded that substantial cost savings and health benefits were possible if all individuals who had conditions that raised cardiovascular risk, specifically diabetes, were diagnosed. Diabetes is responsible for 530 myocardial infarctions and 175 amputations weekly in the UK and the NHS spends £10 billion year on diabetes—10% of the NHS budget—with 80% of this being spent on treating complications of this condition. One in six hospital inpatients has diabetes (Whicher et al, 2020).

Additionally, 90% of strokes are preventable yet there are 100000 new strokes annually in the UK. Stroke care costs the NHS £25 billion per year; each new stroke costs £45000 in the first year, and an estimated £25000 in subsequent years (Patel et al, 2020).

In both women and men, the most significant reason for hospital admissions and cost because of health behaviour is a high BMI. In the UK, among people aged 40–79 years, around 16% of annual hospital costs in men and 19% in women are attributable to excess weight. Musculoskeletal conditions, particularly knee replacement because of osteoarthritis, account for about 40% of the costs attributable to excess weight in both men and women (O'Halloran et al, 2020).

Neuroanatomy in decision-making

From a neuroanatomical perspective, decision-making is a complex cognitive process. People often adapt their immediate behaviour to achieve their objectives. This flexibility in reaching decisions where there are multiple external stimuli involves inhibiting less relevant information, past and present, and considering the consequences of actions; it is often referred as cognitive control (Coutlee et al, 2012).

Each decision made has several stages, referred to as cognitive criteria. The hippocampus stores knowledge and interacts with the prefrontal cortex when decisions are being made. The prefrontal cortex and hippocampus are the most critical parts of the human brain in decision-making.

The prefrontal cortex has three main regions:

- Orbitofrontal cortex

- Anterior cingulate cortex

- Dorsolateral prefrontal cortex.

The orbitofrontal cortex and ventromedial areas are the most relevant to making decision based on reward values, and contribute affective information regarding decision attributes and options.

The orbitofrontal cortex is adjacent to the anterior cingulate cortex and frontal polar cortex—together, they comprise the ventromedial prefrontal cortex—and, with the amygdala and lateral prefrontal cortex, they are responsible for emotional processing.

The anterior cingulate cortex appears particularly relevant in cataloguing conflicting options in addition to indicating outcome-relevant information.

The dorsolateral prefrontal cortex is critical in making decisions where numerous information sources are required.

The prefrontal cortex has connections with striatal and other subcortical areas that influence the function of these cortical regions (Krawczyk, 2002; Rosenbloom et al, 2012). Some conditions, such as trauma and neurogenerative disorders, can impact decision-making networks and provide insight into common lesions affecting decision-making structures (Rosenbloom et al, 2012).

Reflection 1How much education, training and information have you received in relation to decision-making? What was the most useful from your perspective whether in a practice or management role?

Decision-making versus problem-solving

Decision-making is, essentially, a problem-solving activity. Nonetheless, it is important to differentiate between decision-making and problem-solving.

Problem-solving is a systematic process to identify, analyse and resolve issues or challenges. It is a cognitive process in where people review information to understand an issue, seek an effective resolution and reach the desired outcome (Taylor, 2023). The characteristics of problems are that they are easily described and identified, and the cause of the issue can be found from analysing them.

The most likely cause of a problem is usually that which is explained by the facts most easily. This is sometimes referred to as Occam's (or Ockham's) razor (Figure 1). William of Ockham (circa 1286–1347) was a 14th century philosopher and theologian who is often quoted as having said ‘entities must not be multiplied without necessity’ (Schaffer, 2015). The principle is often paraphrased as ‘the simplest explanation is usually the best one’.

From a philosophical perspective, when applying the razor to a problem where there are conflicting theories, both of which carry equal weight, one should consider the theory with fewer assumptions. This does not mean, however, that choosing between these theories would necessarily result in a different prediction or outcome.

Similarly, from a scientific preceptive, Occam's razor is used as a logical approach to problem-solving rather than a rigorous authority when deciding between options in the development of theoretical models. This is referred to as abductive heuristics or, more simply, that there is usually more than one way to solve a problem and the easiest is usually the best one.

Decision-making

Decision-making is a process to reach an optimal or satisfactory solution (Figure 2). The process is based on tacit and explicit knowledge and beliefs.

Tacit or implicit knowledge is relatively difficult to express and record, and its aspects include experiences and intuition. Tacit knowledge is subjective, has a high value, is often context sensitive and specific and is frequently referred to as know-how (Polanyi, 1966). The key to tacit knowledge is experience. It can be captured and shared, for example, when an individual joins a community of practice or through subscription to an academic journal or journal club.

Explicit knowledge is that which can be expressed in words and shared with others in the form of scientific data, principles and procedures. Sometimes referred to as expressive knowledge, explicit knowledge is often viewed as easier to validate than tacit knowledge. For example, the Joint Royal Colleges Ambulance Liaison Committee (JRCALC) paramedic guidelines are explicit knowledge (JRCALC and Association of Ambulance Chief Executives, 2022).

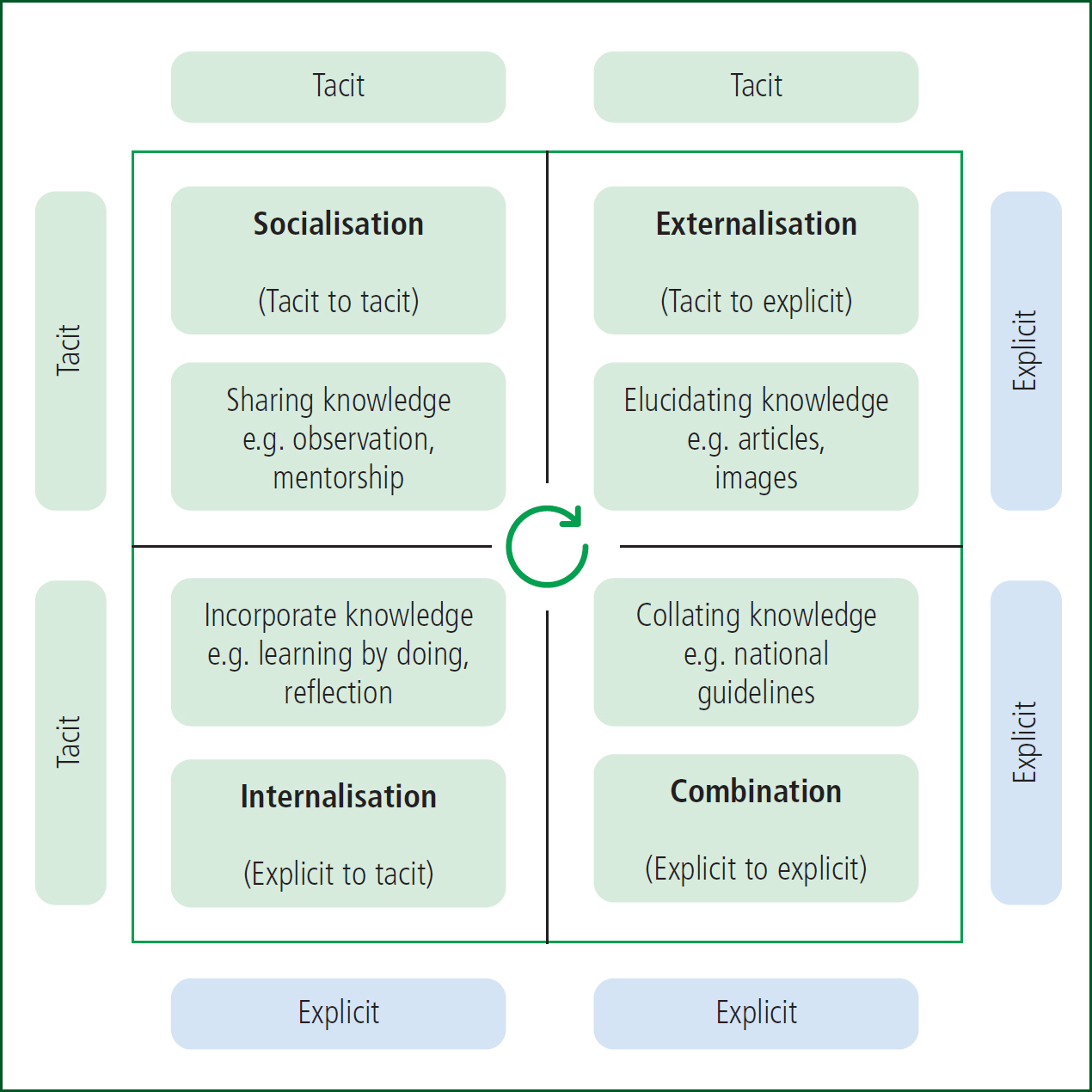

In reality, both types of knowledge are necessary and frequently interact with each other. The Nonaka-Tackeuchi model (Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995) demonstrates the combination of tacit and explicit knowledge, and is also known as the SECI (socialisation, externalisation, combination and internalisation) model (Figure 3). This model is based on a continuous, spiral clockwise process, where interaction occurs between tacit and explicit knowledge.

Its key advantage, specifically in relation to prehospital practice, is that it arguably represents the dynamic nature of knowledge creation and its subsequent impact on patient management. For example, recent developments in independent prescribing for paramedics will allow those who are independent prescribers to prescribe and administer a range of medications to further prehospital time-critical patient care (College of Paramedics (CoP), 2023; HM Government, 2023).

Critics have highlighted the model's limitations, namely the barriers to new solutions being integrated into practice (Bereiter, 2002) and that the issue of new knowledge begins with socialisation (Gourlay, 2006).

Reflection 2Thinking about your experiences as a trainee or student, would further information on supporting decision-making concepts, such as critical thinking, have benefited your clinical practice? If so, can you think of an example of how this would have helped?

Critical thinking, judgement and decision-making

The word critical derives from the word critic, implying critique—employing intellectual capacity or giving a judgement (Oxford English Dictionary, 2023).

The earliest documented records of critical thinking are often associated with the teaching of Socrates (470–399 BC); it was later referred to as Socratic questioning. His student Plato documented his teachings (no chronicles of Socrates exist). Socrates would debate and often argue with his contemporaries on a range of topical moral and ethical issues, frequently coming to no conclusion. He was a polarising figure; in 399 BC, he was accused of impiety (or godlessness) and corrupting the youth with his teachings. He was imprisoned following a daylong trial, sentenced to death and refused offers of help to escape (Visser and Visser, 2019).

In his seminal study on critical thinking and education, Glaser (1941) defined three key aspects of critical thinking:

- l An attitude of thoughtfully considering the problems and subjects that come within the range of one's experiences

- lKnowledge of the methods of logical enquiry and reasoning

- l Some skill in applying those methods.

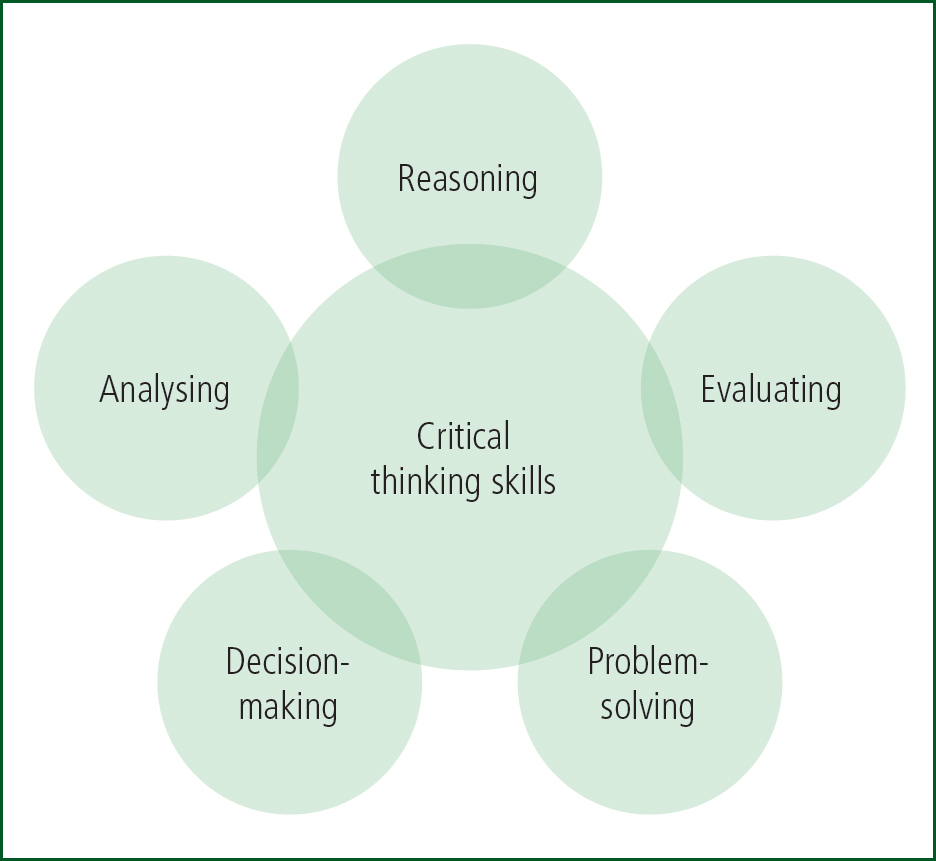

Critical thinking requires a determination to examine any belief or knowledge in the light of evidence. Dewey (1910) argued that, ideally, critical thinking should be embedded in all educational programmes from childhood and that encouraging an ‘ardent curiosity’ and fertile imagination were key to developing the attitude of the scientific mind. Elder and Paul (2007) said critical thinking required self-discipline and that critical thinkers would endeavour to use intellectual tools such as concepts and principles that enable them to analyse, assess and improve thinking. Critical thinkers exemplify the Socratic principle that ‘the unexamined life is not worth living’ Figure 4 suggests critical thinking skills; problem-solving and decision-making are key.

Reflection 3Consider how have you used problem-solving and decision-making in your clinical practice

Bloom's taxonomy

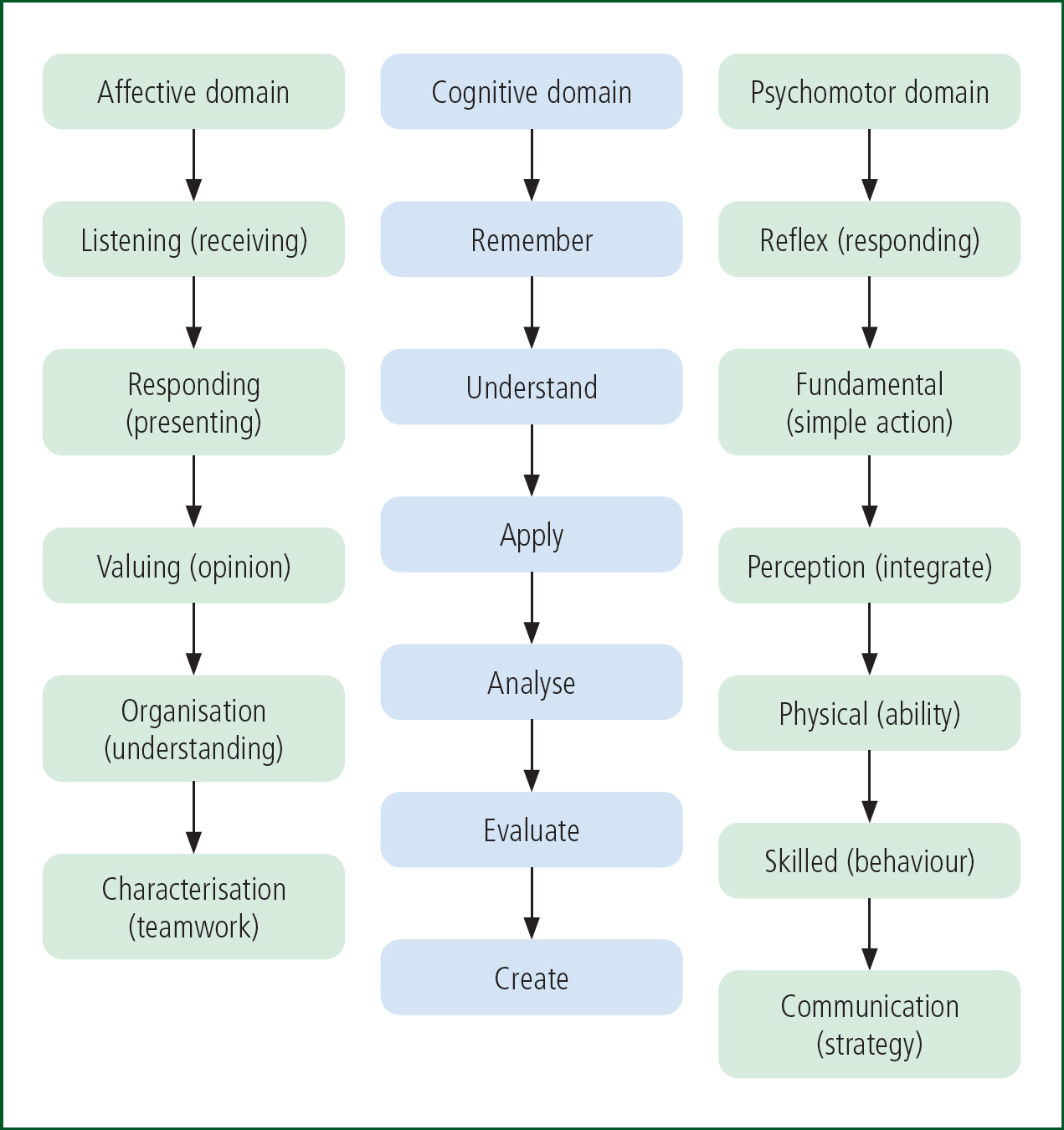

Bloom's taxonomy was originally designed in 1956, and was later refined (Bloom et al, 1984), to determine cognitive educational objectives and assess students’ higher order thinking skills. The original framework consisted of six major categories—knowledge, comprehension, application, analysis, synthesis and evaluation—across the three learning domains of cognitive, affective and psychomotor (Bloom et al, 1984).

Bloom's taxonomy has since been adapted to foster critical thinking, and the revised model involves growth in the psychomotor, cognitive and affective domains as the individual develops their critical thinking skills. Figure 5 outlines the revised Bloom's taxonomy, adapted from Anderson and Krathwohl (2001). Skills should be developed incrementally within the three domains.

The core cognitive domain is related to knowledge, namely thinking and intellect. The recalling of information or knowledge is the base of the pyramid (Figure 6) and is required for all future levels. The affective domain is about emotions and focuses on methods employed to handle feelings, values, appreciation, enthusiasm, motivations and attitudes (Clark and Paulsen, 2015).

The psychomotor domain concerns the ability to physically manipulate a tool or instrument, and includes coordination using motor skills. Development here supports mastery of physical and manual tasks.

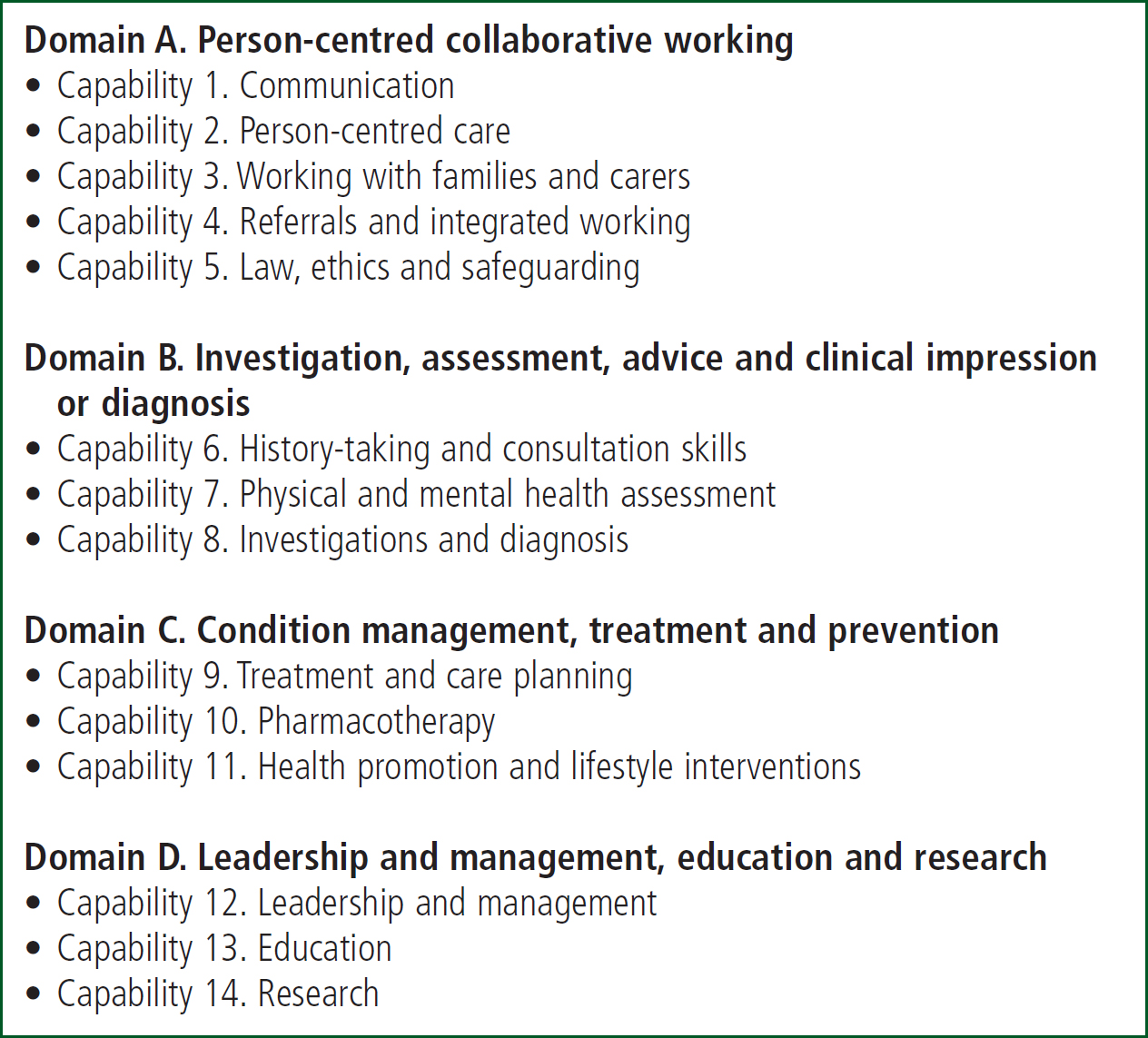

As practitioners ascend through the cognitive, affective and psychomotor domains (Figure 7), the ways in which these domains can be applied to professional practice can be considered as individuals develop clinically. For example, the Paramedic Specialist in Primary and Urgent Care document sets out four domains, based on capabilities (CoP, 2019) (Figure 7). This can be considered perhaps in association with the higher level highlighted in the revised Bloom's taxonomy (Anderson and Krathwohl, 2001) as paramedics develop skills and expertise. Many paramedic capabilities require higher level thinking, skills and competences to provide advanced prehospital care to increasingly complex patient presentations.

Conclusion

Decision-making is fundamental to human behaviour and, as humans have evolved, their brains have developed to perform the complex task of decision-making. This paper has briefly reviewed decisions in terms of health behaviour, such as that affecting the incidence of acute stroke and myocardial infarction, which often present acutely in prehospital care.

Decision-making is essentially a problem-solving activity, but problem-solving is a more systematic process. Critical thinking is key to all clinical practice and, arguably, forms the basis of knowledge when practitioners are considering evidence. It is a key skill in both theory and practice. Bloom's taxonomy, while developed to assess cognitive educational objectives and higher order thinking skills, could be applied in the development of advanced paramedic roles and their application to prehospital care and clinical outcomes.

The second and final article in this series will look in more depth at decision-making theory and how this can be applied to prehospital clinical practice.

Reflection 4Can you apply Nonaka-Takeuchi model's continuous spiral clockwise process to the dynamic nature of knowledge creation and the subsequent impact on patient management?