LEARNING OUTCOMES

After completing this module, the paramedic will be able to:

If you would like to send feedback, please email jpp@markallengroup.com

An antepartum haemorrhage (APH) is any frank blood loss from the genital tract between 24 completed weeks of pregnancy and the onset of labour. APH occurs in and complicates 3–5% of pregnancies (Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG), 2011). It is often unpredictable and, because the pregnant woman is able to compensate because of the physiological adaptations of pregnancy, deterioration is often rapid and unexpected. The patient can lose up to 35% of her circulating blood volume before signs of deterioration can be identified on observations (RCOG, 2011).

According to the Advanced Life Support Group (2018), several risk factors increase the risk of experiencing a non-trauma related APH:

In trauma-related cases, there is an increased risk of APH in:

The RCOG (2011) green-top guideline on APH uses the following terms to described blood loss from an APH:

Common causes of minor APH include cervical erosion, severe vaginal thrush infection and marginal placental bed bleeding.

Major APH mainly results from placental abruption and placenta praevia, which are discussed below.

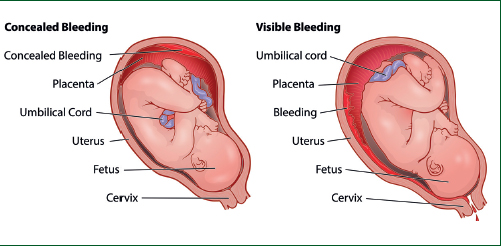

It can be difficult to estimate blood loss from APH prehospitally as it can be either concealed and not visible externally or revealed with visible bleeding (Figure 1).

Revealed blood loss is more commonly a results of placenta praevia because the location of the placenta means there is an easy exit for lost blood. Concealed haemorrhage is normally a result of trauma, assault or any blunt force to the uterus that causes the placenta to shear off the uterine wall.

Any blood loss over 30 ml should be investigated with the aim of determining its source. In the prehospital setting, the exact reason why a woman is bleeding does not need to be identified; the key is to recognise there is bleeding or the woman is losing blood internally and act upon this quickly. Minimising time on scene is the only way to save a woman and her baby during a major APH. The key is to remove the woman to the nearest definitive care facility rapidly without delay.

Reflection 1

Given the risk of antepartum haemorrhage following a trauma-related incident, should pregnant women with any amount of bleeding always be conveyed to an obstetric unit?

Placental abruption

A placental abruption is where a portion of a normally sited placenta pulls away from the uterine wall causing bleeding, which can be of various amounts.

At term, >700 ml/minute of blood is provided to the uterus (Open Anesthesia, 2018) so, if any portion of the placenta is pulled or forced away from the uterine wall, catastrophic bleeding can ensue very quickly. Blood loss from an abruption can be both concealed and revealed (Figure 1). This makes diagnosis difficult.

The signs of a placental abruption are:

Reflection 2

Thinking about the last case of antepartum haemorrhage that you attended, what score on the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists scale would you have given it?

Causes

The exact causes are of placental abruption are unknown. However, it can follow direct trauma to the abdomen from an assault, a road traffic collision or a fall directly onto the abdomen.

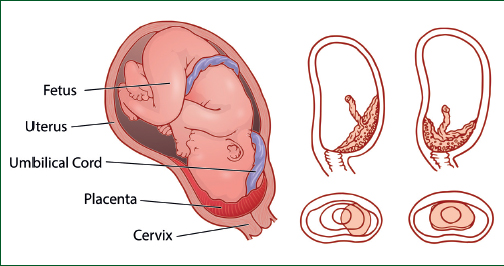

Placenta praevia

A placenta praevia is a placenta that develops in the lower segment of the uterus rather than in the normal upper portion. The placental bed can completely cover the cervix, which makes bleeding inevitable. Pregnancies complicated by placenta praevia always require a caesarean section for the birth of the baby.

Unlike an abruption, a placenta praevia tends to cause painless bleeding. It is a rare condition occurring in approximately one in 200 pregnancies (AACE, 2024). Women who have the condition will be aware of the risks and concerns as it will have been detected during their 20-week ultrasound scan. Of course, it is identified only if the woman attends for a scan, so be cautious with women who have concealed their pregnancies or not attended antenatal care.

A typical presentation in women who have placenta praevia is painless vaginal bleeding because of where the placenta is sited; blood is frank and bright red in nature.

Women often experience several bleeds during their pregnancy, which may be only spotting. This can serve as a warning regarding haemorrhage, often alerting a woman that a more severe bleed may occur.

The degree of shock a woman is in will often be directly proportionate to the blood that is visible as it will drain out of the uterus into the vagina.

As stated above, the prehospital clinician does not need to know whether the bleeding is resulting from an placental abruption or a placenta praevia, the treatment is the same: the woman should be moved to definitive care as soon as possible.

Key differences between placental abruption and placenta praevia are shown in Table 1.

| Clinical sign | Placenta praevia | Placental abruption |

|---|---|---|

| Warning haemorrhages | Yes | No |

| Abdominal pain | Usually painless | Yes, can be severe |

| Blood loss; colour | Frank; fresh red | Dark red/brown |

| Onset | At rest, post coital | After exertion/trauma |

| Degree of shock | Proportional to loss | Disproportional to loss |

| Consistency of uterus | Soft, non-tender | Tense, hard,’wooden' |

Treatment and management

Rapid assessment of the patient is vital when dealing with an APH. It can rapidly become a time-critical, life-threatening emergency and rapid transport to an obstetric facility is vital, with time on scene minimised.

Following an initial DrCABCDEF (danger, response, catastrophic bleed, airways, breathing, circulation, disability and examination) approach as with a normal primary assessment, paramedics should ensure the mother is conveyed as soon as possible. There should be no time delays on scene; this is especially important if there is haemodynamic instability.

The mother should be conveyed in a position of comfort. This is normally a semi-recumbent position; however, where consciousness is reduced or lost, she can be transported in the right lateral position so paramedics can monitor her airway to avoid further foetal compromise and prevent supine hypotension syndrome (where the gravid uterus occludes the vena cava preventing adequate venous return).

Oxygen saturation should be monitored. If this falls <94%, oxygen therapy should be provided as per JRCALC guidance (Association of Ambulance Chief Executives (AACE), 2024).

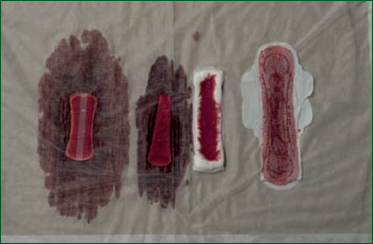

Paramedics should asses the amount of bleeding they can see and take any blood-soaked pads with them to the obstetric unit. Different products will vary in appearance and absorb different amounts. All the products in Figure 3 have the same 50 ml of ‘blood’ in them, but look very different. The same applies if the blood is in water such as down a toilet. The blood dissipates and the volume often appears greater than the amount that has been lost.

Syntometrine or misoprostol must not be administered for an APH as the foetus is still in situ. Tranexanamic acid may be considered but must be administered only in accordance with the trust’s patient group directive.

No delays on scene should be allowed for cannulation. This should be done en route if bleeding is serious. Continuous access with two large-bore cannulas should be sought early as maternal shutdown often occurs quickly because of sudden onset of hypovolaemic shock. Paramedics should cannulate with the largest bore cannula possible, ideally 18 g or above.

Intravenous fluid therapy should be used to maintain a systolic blood pressure of >90 mmHg by giving 250 ml bolus doses of sodium chloride. However, it is important to remember that pregnant women may lose up to 35% of their circulating blood volume without a significant change in their observations.

Careful assessment of foetal movements should be made to assess foetal viability.

Paramedics should remember patient pain and titrate pain relief accordingly. The use of paracetamol, Entonox (50% nitrous oxide and 50% oxygen) and morphine may be considered according to the pain score. Morphine should be used with caution, especially if the woman is hypotensive and at risk of respiratory depression.

The woman must be kept nil by mouth and allowed to adjust her position according to what feels comfortable for her.

A concise pre-alert should be sent to the receiving obstetric facility, including an estimation of blood loss so staff can gather the assistance needed to deal with specific events. The SBAR (situation, background, assessment, recommendation) handover tool would be a format for the pre-alert message.

Reflection 3

Paramedics need to be sensitive as anxiety and alarm may exacerbate maternal stress. Would asking if the baby is moving cause further distress or alarm?

Reflection 4

If there is difficulty in accessing the obstetric unit, would asking a member of staff to meet you at the door assist in a more swift and rapid arrival?

Reflection 5

Thinking about the last antepartum haemorrhage that you attended, what were your initial thoughts on the origin of the bleeding and what were your actions on this case?

Case studies

You are responded to a 38-year-old woman who is 35/40 pregnant with her fifth pregnancy. She speaks virtually no English but has a set of handheld pregnancy records so you deduce she has been to see a midwife in this pregnancy.

As soon as you walk through the door, you can see she has bright red blood dripping down her legs and pooling at her sandals. She is very anxious but states she has no pain.

What are your initial thoughts?

Case study 2

You are responding to Lucy Smith, a 23-year-old G2P1 (pregnant twice, one live birth at term) who is 30/40 pregnant.

She was out with her mother in a shopping centre and slipped and fell down three steps, landing directly on her abdomen, about an hour ago.

Since the fall, she has had a painful, tender area over the point of impact but no pain elsewhere else and her cervical spine is clear.

She called 999 as she is feeling dizzy and faint. Her blood pressure is 100/60mmHg, heart rate is 110 beats per minute and her respiratory rate is 28 breaths per minute.

What are your initial thoughts?

You suspect she is bleeding internally, possibly from her placenta, and decide correctly, even though there is no visible bleeding, to alert the nearest obstetric unit to her.

You provide an SBAR handover for the midwifery team treating her (Table 2).

| Situation | Lucy Smith 23-year-old G2P1 30/40 |

| Background | Fall direct onto abdomen approximately 1 hour ago |

| Assessment | Tender area sore to touch directly over fall impact point BP 100/60; HR 110 bpm; RR 28/min No PV loss ww Feeling faint and dizzy |

| Recommendations | Believe the patient may be suffering a placental abruption could a team be ready to meet the ambulance at the ambulance entrance to enable swift access to obstetrics unit please ETA 8 minutes |

PV loss: per vaginam bleeding: vaginal bleeding