This reflective essay uses Gibbs' (1988) model (Figure 1) to evaluate the management of a dilemma involving a patient who disclosed domestic abuse. This simple model was chosen to structure a critique of this experience, using its cyclical nature to prompt what changes should be made to deliver better care to this patient group in future.

The patient refused referrals to the police and safeguarding team when offered these by the author, a student paramedic, who was working with an emergency care assistant and a paramedic mentor. The dilemma surrounds whether behaviours of coercion and control impact a patient's freedom to consent to or refuse care.

In this article, key terms are defined to establish the context of the case after which the conduct of the student paramedic is evaluated. The medical, ethical and legal aspects of the case are considered and compared to the professional standards for paramedics (Health and Care Professions Council (HCPC), 2016; 2023). Compassionate scrutiny of why the patient made her decisions establishes whether subsequent actions should be repeated were the author to face a similar dilemma in future.

Free and informed consent relies on the person having capacity to make the decision required as well as being free from influence by others (Herring, 2016). Capacity is specific to each decision required of an individual and can fluctuate with time (Herring, 2016).

The diagnostic first stage of the two-stage test in the Mental Capacity Act 2005 determines the person's issue-specific capacity in light of capacity-impacting factors, including intoxication from alcohol or drugs, psychological conditions and physical illness (Barton-Hanson, 2018). This is followed by examining their functional ability to:

- Understand the information relevant to the decision

- Retain that information

- Use or weigh up that information and

- Communicate their decision (Barton-Hanson, 2018).

The patient discussed in this article was assessed to have capacity to make her own decisions, which added to the dilemma in managing her disclosure.

Controlling behaviour aims to make a person subordinate, depriving them of independence in acts or decisions, while coercion is a pattern of assaults, threats or intimidation that aims to punish or frighten another, including to influence their decisions (Lehmann et al, 2012). Whether through incapacity, coercion or controlling behaviour, being unable to give informed consent substantially affects a person's ability to make their own decisions (Barton-Hanson, 2018). In such cases, clinicians may make best-interests decisions for patients, taking account of all available information, having first fully supported the individual to make their own decisions (Barton-Hanson, 2018). The dilemma surrounds whether the patient's decision was valid in the context of controlling behaviour.

Reflective practice is the ability to reflect on actions in order to undertake continuous learning (Schön, 1983). The HCPC (2023) requires paramedics to be critically self-aware, and reflection increases self-understanding and awareness of oneself as a professional (Jaastad et al, 2022). Undertaking this reflection has enabled the author to recognise the limits of his understanding of the complex medico-ethico-legal framework surrounding domestic abuse, consent, coercion and controlling behaviour. Improving this understanding empowers the author to establish others' influence on future patients' decisions and safeguard against coercive or controlling behaviour. Future patients will receive better care following this reflective learning.

Description

The dilemma involved a woman aged 56 years who was offered transport to hospital for specialist psychiatric assessment during a mental health crisis. She accepted this offer and was taken to the emergency department.

En route to hospital, the patient described subtle behaviours of control by her spouse, primarily making derogatory comments about her appearance and being quick to lose his temper if the house was not spotlessly clean on returning home. These were recognised by the student paramedic as psychological and verbal forms of domestic abuse (Butler, 2022). The student paramedic sought informed consent to make referrals to the police and safeguarding team, but the patient refused.

The patient was a homemaker, which made her financially dependent on her spouse. She displayed a pattern over preceding years of turning to alcohol as a coping mechanism during phases of low mood, paralleled in this encounter. During the conversation en route to hospital, the patient recounted previous instances of violence towards her that she had reported at the time, but stated she would never report her spouse to the police again. The nature of the dilemma is whether the patient's freedom to give informed consent was impinged by coercion or control by her spouse.

The patient consented to all assessments and was deemed to have capacity at the time, using structured capacity assessment tools (Barton-Hanson, 2018; Association of Ambulance Chief Executives (AACE), 2022). Her alcohol intake was found not to cause functional impairment so did not prevent her from having capacity under the two-stage test in the Mental Capacity Act 2005 (Barton-Hanson, 2018; AACE, 2022).

This competent adult's refusal was respected; no referrals were made. However, no consideration was given to whether her refusal was the result of controlling behaviour by her spouse.

Feelings

The author was confident in his assessment of the patient's capacity and competence during the encounter.

However, once the patient had disclosed the abuse and refused referral, he was uncomfortable with the disclosure not being taken forward, despite this being the patient's wish.

Discussion with the paramedic mentor at the time did not allay those feelings of unease. Accepting the patient's refusal of onward referral appeared to perpetuate the issue of domestic abuse incidents not being resolved with appropriate proactivity or seriousness, which has been identified as a common issue in domestic abuse cases (Birdsey and Snowball, 2013).

Evaluation

Management of safeguarding concerns and refusals of care sit in a complex legal and ethical context. The first legal duty on clinicians is under the Mental Capacity Act 2005 to respect the wishes and choices of an adult who has capacity. These choices do not have to seem sensible or logical to others as the right to make decisions deemed unwise by others is protected by this legislation. In the case described, the patient was repeatedly assessed to have mental capacity so the attending crew acted lawfully in not making a referral against her wishes. The legal complexity of mental capacity contributed to the dilemma of whether the patient's refusal was valid.

As well as acting lawfully, the attending crew acted ethically in their treatment of this patient. Respecting a patient's wishes prioritises their autonomy—the first principle of biomedical ethics described by Beauchamp and Childress (2019). Taking the non-maleficence principle (Beauchamp and Childress, 2019), one can further justify following the wishes of an individual rather than disregarding these and risking harm resulting from disrespecting the person (Buchanan, 2004). In this way, the attending crew acted both ethically and lawfully when not making police or safeguarding referrals.

An alternative ethical perspective on this case highlights the lack of beneficence conferred on this patient. Promoting and protecting patients' wellbeing forms the core of Beauchamp and Childress' (2019) principle of beneficence when applied to medical ethics. In this case, reporting the allegations despite the patient's wishes would have been justifiable as beneficent. Conversely, by respecting the patient's wishes, the student paramedic declined to take protective action on her behalf, lacking beneficence. The actions taken may not have been purely ethical under the beneficence approach.

A conflicting legal standpoint arises from the Serious Crime Act 2015 and Domestic Abuse Act 2021. Respectively, these criminalise coercive and controlling behaviour and streamline the process for police to issue domestic abuse protection notices to prevent further abuse (Bekaert et al, 2022). The legislation permits investigation and prosecution when the survivor of abuse chooses not to pursue the case (Herring, 2016; Crown Prosecution Service, 2022).

Protecting vulnerable patients from future harm falls under the safeguarding duties of professional standards (HCPC, 2016; 2023) and in the Care Act 2014 (Department of Health and Social Care, 2016).

Breaking confidentiality on the premise that survivors of abuse are vulnerable adults requiring paternalistic protection deprives them of their autonomy (Herring, 2016). Nonetheless, the crew could be legally justified in referring the patient to police or safeguarding teams without their consent outside capacity legislation, adding to the dilemma.

Analysis

Survivors of domestic abuse often take steps to protect the perpetrator, particularly when they are acquainted (Birdsey and Snowball, 2013). As the patient's allegations were against her spouse, one must consider the impact of this relationship on the patient's decision. One could empathise that love may affect a person's judgement of the perpetrator's actions or how to respond. The literature examines this inverse relationship between involvement of police and closeness of relationships (Heron et al, 2022). Their relationship may have influenced the patient's decision to not report the abuse.

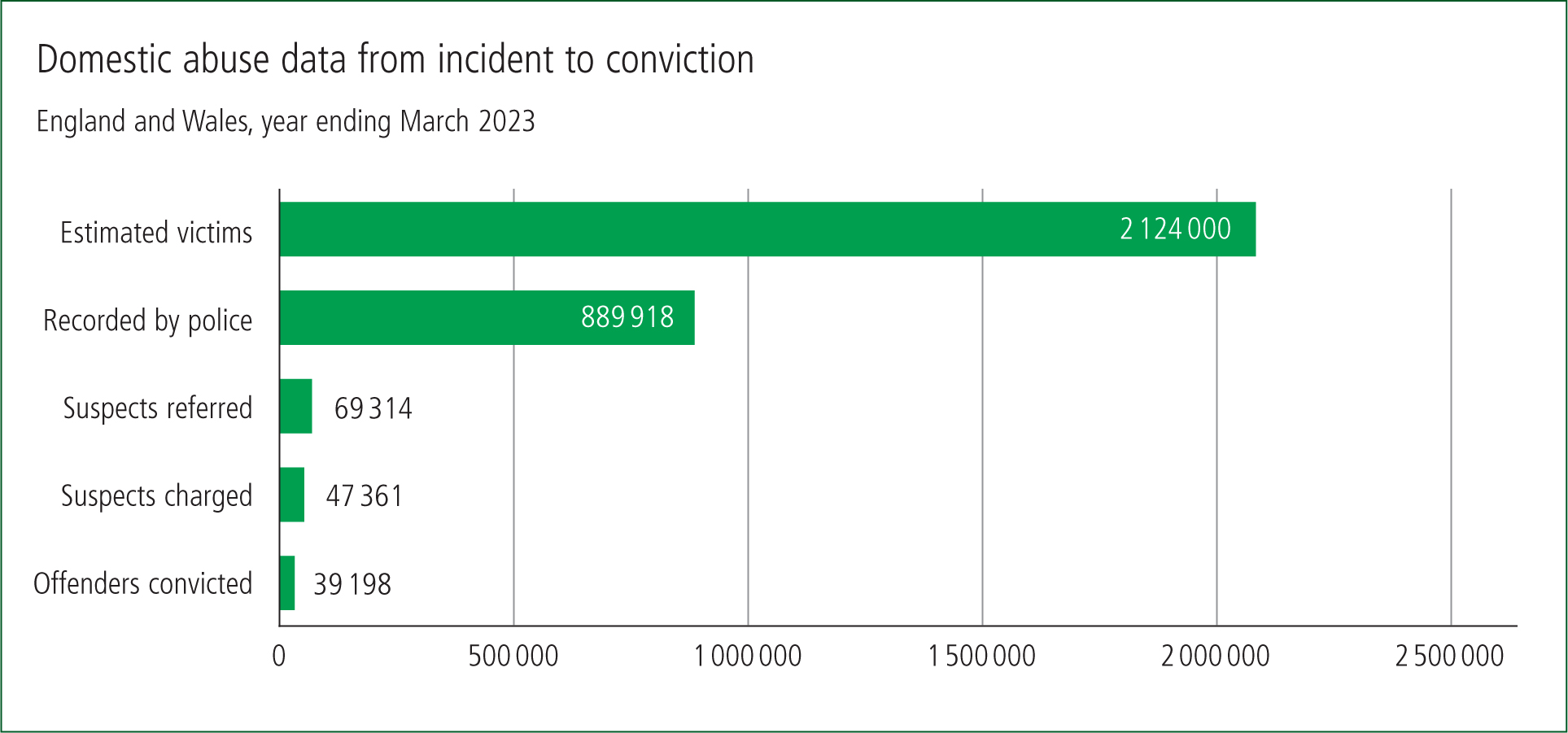

Fear of reprisal for speaking out could further prevent survivors of domestic abuse from reporting their experiences. This was the most common reason for those attending domestic violence refuges in Australia to not report abuse to police (Birdsey and Snowball, 2013). In Reich et al's (2022) US-based study using thematic analysis of social media posts explaining reasons for not reporting domestic abuse, 34% of posts were coded as ‘expecting a negative reaction’ and another 33% as ‘perpetrator actions’, including the sub-themes of verbal and physical threats (5%), as well as denial, excuses, manipulation or public slander (9%). In the UK, the Office for National Statistics (2023) recorded 889 918 domestic abuse reports made to police in the year to March 2023 out of an estimated 2.1 million cases (67% female) (Figure 2). This equates to a reporting rate of 42%.

One cannot infer whether the patient discussed had experienced a reprisal from her spouse after reporting a previous incidence of violence, but it could explain her reluctance to report her spouse again. Clinicians have a duty of care to patients in this situation and must work alongside other agencies to protect them from all forms of abuse (HCPC, 2016; 2023; Stanley, 2016; Butler, 2022). However, it would not be conducive for patients' wellbeing to expose them to potential reprisal following their disclosure. Clinicians must ensure they balance the risk of continuing domestic abuse with the risk of reprisal following a report when navigating dilemmas in this field.

Another factor to consider is the patient's financial dependence on her spouse, coupled with her employment status as a homemaker. Low-independence economic security is associated with poorer long-term outcomes of domestic abuse (Speed and Richardson, 2022).

Although the original research is set in Australia, Canada and the UK, all three countries have similar liberal-regime welfare states under Esping-Andersen's (1990) seminal typologies (Pförtner et al, 2019). Since welfare benefits in these systems are relatively modest compared with the social democratic welfare regimes of Scandinavian countries (Pförtner et al, 2019), citizens with fewer resources will still depend on favourable market forces to maintain their standard of living, or experience health and social inequalities as a direct result of their low socioeconomic security (Brennenstuhl et al, 2012; Pförtner et al, 2019). Avoidance of poverty may take priority over leaving an abusive relationship so a lack of financial independence could have deterred the patient from reporting her allegations to the police (Heron et al, 2022).

The crew did not consider this socioeconomic complexity when evaluating the patient's decision and simply took her refusal at face value. In doing so, they may have overlooked a key influence in the patient's decision.

It is possible that neither the student paramedic, nor their mentor, had sufficient understanding of the support available to this patient. One key protection is the domestic abuse protection order (Speed and Richardson, 2022), instigated by the Domestic Abuse Act 2021.

Health professionals have a role in education, health promotion and empowering healthy behaviours (Bekaert et al, 2022). Part of this role involves signposting patients to support and resources that reflect their biopsychosocial needs (Bekaert et al, 2022; HCPC, 2023). The attending crew being able to explain the legal protection available would have allowed accurate and thorough patient education, enabling her to make a fully informed decision. Better understanding of the legislation would have empowered the student paramedic to signpost the patient to more appropriate legislative and psychological support mechanisms, improving her outcomes.

Conclusion

This reflection has examined whether coercive or controlling behaviours impacted a patient's freedom to consent to or refuse care, considering the relevant evidence, legislation and professional standards. The student paramedic author has argued that the attending crew acted lawfully and ethically following the patient's disclosure of domestic abuse. The patient's decisions were respected, despite them seeming unwise.

However, the student paramedic did not consider whether the patient's decisions were unduly influenced by her abuser. Significantly more weight should have been put on establishing the impact of control by others and identifying safeguarding needs than on the patient's mental capacity to refuse referral.

He should have used his rapport to fully explore and examine the situation, and probe deeper into why the patient refused, rather than focus on her capacity to refuse. This may have highlighted a further concern to address, such as the patient fearing reprisal following a safeguarding enquiry.

Better understanding of key legislation, particularly around domestic abuse protection orders, could have provided the opportunity to better support this patient.

Action plan

Reflection on this case has allowed the author to recognise the limits of his understanding of the complex medico-ethico-legal framework surrounding domestic abuse, consent, coercion and controlling behaviour. In response, he has established a new methodology to compassionately assess the full extent of the alleged abuse and the underlying reasons for refusing a safeguarding referral. This will empower the author to establish the influence of others on patients' decisions and safeguard against coercive and controlling behaviour. He could then signpost the patient to appropriate legal and psychological support mechanisms, including how to seek a domestic abuse protection order. This should prevent similar patients' refusals of safeguarding referrals being accepted with minimal critical analysis, simply because the patient has capacity. Future patients with similar presentations will receive better care as a result of this reflective learning.

Future work could include developing a structured assessment tool to help clinicians compassionately assess the reasons behind patients refusing safeguarding referrals. Aiding assessment of this complex situation should strengthen clinical decision-making and improve patient care.

Key Points

- A patient's decision to refuse a safeguarding referral after a disclosure of domestic abuse can be impinged by coercion or control by their alleged abuser

- A patient can have many reasons for refusing a safeguarding referral after a disclosure of domestic abuse. Practitioners should probe these further as a priority

- The legal and ethical balance of autonomy, beneficence and the right to make decisions deemed unwise by others should be navigated carefully

- Better support can be provided to patients who refuse help for domestic abuse if the reasons for refusal are explored more

CPD Reflection Questions

- What features of this patient's presentation would prompt you to consider there was a safeguarding risk?

- Which ethical standpoint would you prioritise if faced with a similar situation and why?

- Does your workplace have any guidance on how to handle refusals of safeguarding referrals?