In 2020, the world faced an unprecedented pandemic, greatly affecting healthcare services and communities. As a result, national legislation – the Coronavirus Act – was imposed in the UK to mitigate the effects of coronavirus on healthcare staff, patients and the public.

COVID-19 restrictions prevented paramedic students training with ambulance service-partnered universities from completing their clinical placements. Meanwhile, universities were closed, requiring all teaching to be transferred online, leaving many individuals to miss months of essential clinical experience in practice and in simulation (Hubble et al, 2021).

Three recurring topics were identified within the existing literature as causing the most disruption to the usual modus operandi for paramedic education and clinical practice: moving online; reduced time in simulation; and cancelled clinical placements.

The themes were identified during a critical review of the existing literature, using PubMed and CINAHL databases. Search terms including ‘COVID-19’, ‘paramedic’, ‘education’, ‘healthcare’ and ‘student’ highlighted 28 articles, which were reviewed as part of a preparation for research activity for this MSc project.

Themes in the literature

Moving online

Online education became the primary mode of teaching in 2020, as on-campus learning became difficult to manage safely for large cohorts.

Students faced cancelled exams and limited face-to-face contact, resulting in lectures being provided online via video link (Coughlan, 2020). While learning online can be beneficial and continues to be widely embraced through hybrid learning, there is an argument that it does not replicate the conventional hands-on methods essential in healthcare education (Pather et al, 2020). Studies indicate that, although students prefer online learning for theoretical components, they find it significantly less effective for practical skills development (MacQueen, 2013; Perkins et al, 2020).

Engagement with online learning can be variable, as students self-report decreased levels of attention, higher levels of anxiety and poorer retention of information during video lectures (Risko et al, 2012; Farley et al, 2013; Williams et al, 2021). Online learning may be less impactful for students who feel less motivated or have more distractions at home, as discussed by Perkins et al (2020), who investigated student paramedics during COVID-19.

Despite these disadvantages, work-from-home learning was promoted as many institutions successfully met the demand to fulfil students' educational needs (Newman and Lattouf, 2020).

Reduced simulation time on campus

Healthcare simulation allows students to demonstrate clinical skills safely, to reproduce scenarios that may not be seen in practice, and provides a semi-realistic experience of patient management (Wheeler and Dippenaar, 2020). Reducing time in simulation by moving studies online significantly reduces these benefits.

Following an extensive literature review of 53 studies, Negri et al (2017) positively credited the use of simulation with a multitude of benefits for students, including correcting poor technique and boosting confidence. Abelsson et al (2014) noted that simulation is particularly useful in trauma and paediatric emergency medicine, or when managing presentations seen less frequently in clinical practice.

COVID-19 restrictions forced universities to change how students learned in practical environments, creating COVID-friendly ‘bubbles’ to maintain compliance against infection, while still delivering face-to-face teaching (Department for Education, 2020; Gill et al, 2020).

Anderson et al (2019) suggested some students were disproportionately affected by a lack of regular simulation opportunities, which was compounded by a less comprehensive range of conditions experienced on their clinical ambulance placements.

More importantly, an absence of simulation prevents the recognition of problems and provision of support mechanisms to students who may be underperforming, be experiencing burnout or are severely lacking in confidence (Hall et al, 2020).

The combination of these factors leaves students feeling underprepared, highlighting the impact COVID-19 may have had on their simulation experience.

Cancelled clinical placements

COVID-19 led to clinical placements for student paramedics within NHS trusts being cancelled. Placements, which are used to consolidate theoretical learning and apply it in practice, are highly valued by student paramedics in the UK, with students reporting positive experiences, despite not always encountering a wide range of patient presentations (Michau et al, 2009).

These placements should incorporate non-ambulance settings, such as maternity care, as evidence recommends students should have opportunities to improve confidence and put theory into practice with other expert health professionals and that these should not be undervalued (Lenson and Mills, 2018; Credland et al, 2020).

As placements bridge the gap between simulation and practice, providing experience of hands-on practice, interprofessional working and leadership skills, student paramedics may be negatively impacted by not having this experience. This underlines the argument that significant time gaining clinical exposure through placement is beneficial to the student paramedic, building confidence and relieving pressure by having mentored support during stressful situations (Dyson et al, 2017). These skills empower decision-making and teamwork skills for use in future practice. However COVID-19 restrictions removed these opportunities.

Paramedic students were not alone regarding the cancellation of clinical placements. UK studies investigating the disruption of COVID-19 on healthcare and medical students strongly indicate that students training to be junior doctors and community nurses were negatively and profoundly affected by COVID-19 (Choi et al, 2020; Whiting et al, 2023).

It is highly possible that strong similarities exist with paramedic students, catalysed by missed opportunities to fulfil essential skills in simulation at university, thus creating a void in clinical exposure.

Aim

The advantages and disadvantages to UK paramedics resulting from changes to their education owing to COVID-19 restrictions had not been identified in the literature at the time of this study in 2021.

The aim of the research was to investigate whether undergraduate paramedics felt COVID-19 restrictions impacted their education and clinical experience.

The objectives were to survey a group of undergraduate paramedics affected by restrictions and identify which issues students feel COVID-19 caused the most disruption.

Research design

This study employed a quantitative, observational approach using a cross-sectional design to assess the perceived impact of national COVID-19 restrictions on paramedic students' undergraduate education. Owing to the infeasibility of an experimental design, observational data collection was deemed the most appropriate.

An online survey was administered to third-year paramedic students at three universities affiliated with one UK ambulance service. Data collection occurred between April and June 2021.

The survey involved a five-point Likert scale and multiple-choice questions, similar to that used by Choi et al (2020). Rolak et al (2020) and Choi et al (2020) identified key themes from medical student education affected by COVID-19, with parallels that are relatable and overlap with paramedic student education. These were therefore used as a basis for the methodology design used in this study, following an already established framework.

A pilot survey was carried out online with four student paramedic colleagues to ensure the instrument was user-friendly and appropriate.

Methodology

The data is reported in line with STROBE guidelines (von Elm et al, 2008).

Sample

Recruitment involved gaining permission to access third-year paramedic students studying at four universities who share their placements with the same UK ambulance service.

In total, there were 110 potential student participants. One university did not respond during the data collection period, leaving a maximum sample of 88.

The survey was distributed online via social media platforms and sent by internal email from the programme leads of the three universities to all students meeting the inclusion criteria.

Only final-year paramedic students on placement with the London Ambulance Service during the 2021–2022 academic year were included. A follow-up email was sent after 3 weeks to improve the response rate. In total, 29 students completed responses.

Data collection

Online survey responses are notoriously difficult to obtain, with average response rates of 20–30%, which can be difficult to improve as many potential participants may not be willing to be involved (Safdar et al, 2016).

The survey incorporated 30 preset questions to all participants, some of which were adapted from previous research studies, looking at the impact of COVID-19 restrictions on healthcare staff (Rolak et al, 2020; Choi et al, 2020). Questions were designed to concern changes specific to paramedic education and clinical placements.

Likert scales are often open to distortion through various factors, including central tendency as well as acquiescence and social desirability bias, resulting in less reliability of data (Althubaiti, 2016). Conversely, it has also been discussed that people tend to be quicker when responding to questions in Likert format, following their initial instincts on selecting an answer, which suggests they are more attractive to respondents than open-ended questions, which require more time and consideration (Kreitchmann et al, 2019).

However, even with a closed-question Likert survey, in this instance there were a total of only 29 final completed responses and, as such, there is insufficient data to be generalisable to the overall target population, despite interesting trends from the data.

Ethics

Institutional ethics approval was granted before data collection. Informed consent was gained from all participants via the online survey.

Approval was granted by the University of Hertfordshire's health, science, engineering and technology Ethics Committee with Delegated Authority (ECDA), with no amendments to the study terms required throughout the period of data collection, under protocol number HSK/PGR/UH/04521.

Personal data were securely stored without identifiable information for 12 months before being destroyed.

Results

Stacked bar charts were used to analyse data across three areas: online learning; reduced simulation time; and cancelled clinical placements.

Of the 29 respondents, six (21%) were male and 23 (79%) were female, and they were aged 18–26 years. The distribution included 12 (41%) students from both university A and B, and five (17%) from university C.

Online learning

Seventeen students (59%) reported that COVID-19 restrictions negatively impacted their theoretical education, while 22 (76%) felt less motivated learning at home compared to at university.

When determining whether students feel comfortable asking questions and participating in online sessions, 10 students (34%) generally agreed they did.

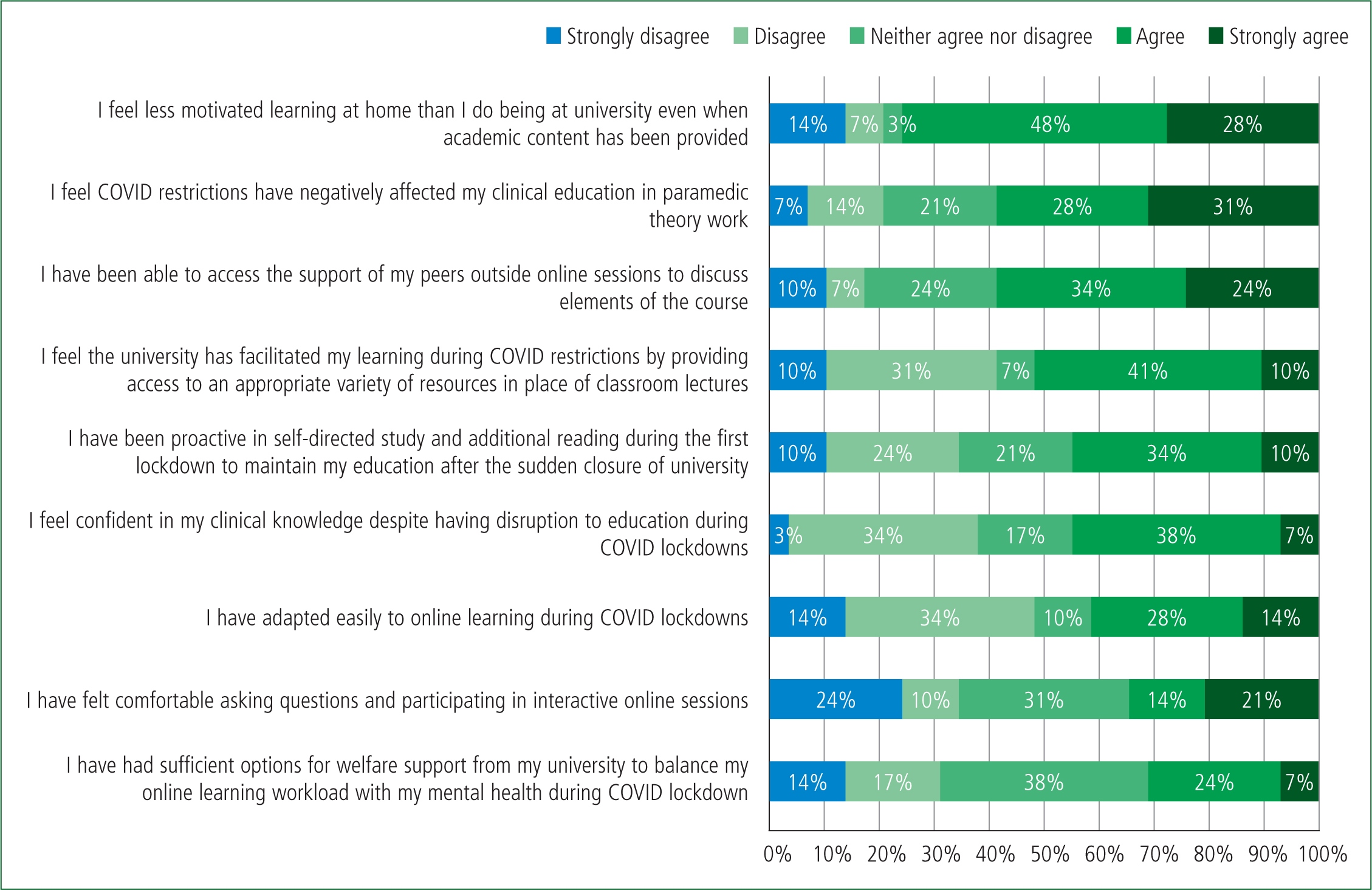

Figure 1 illustrates a 100% stacked bar chart summarising students' responses to statements about their learning experiences during COVID-19 lockdowns. The most prominent finding is that 76% of students (n=22) felt less motivated learning at home compared to on campus, even when teaching resources were provided.

Additionally, only 31% of students (n=9) felt they had sufficient welfare support from the university to balance their online learning workload with their mental health during the lockdown.

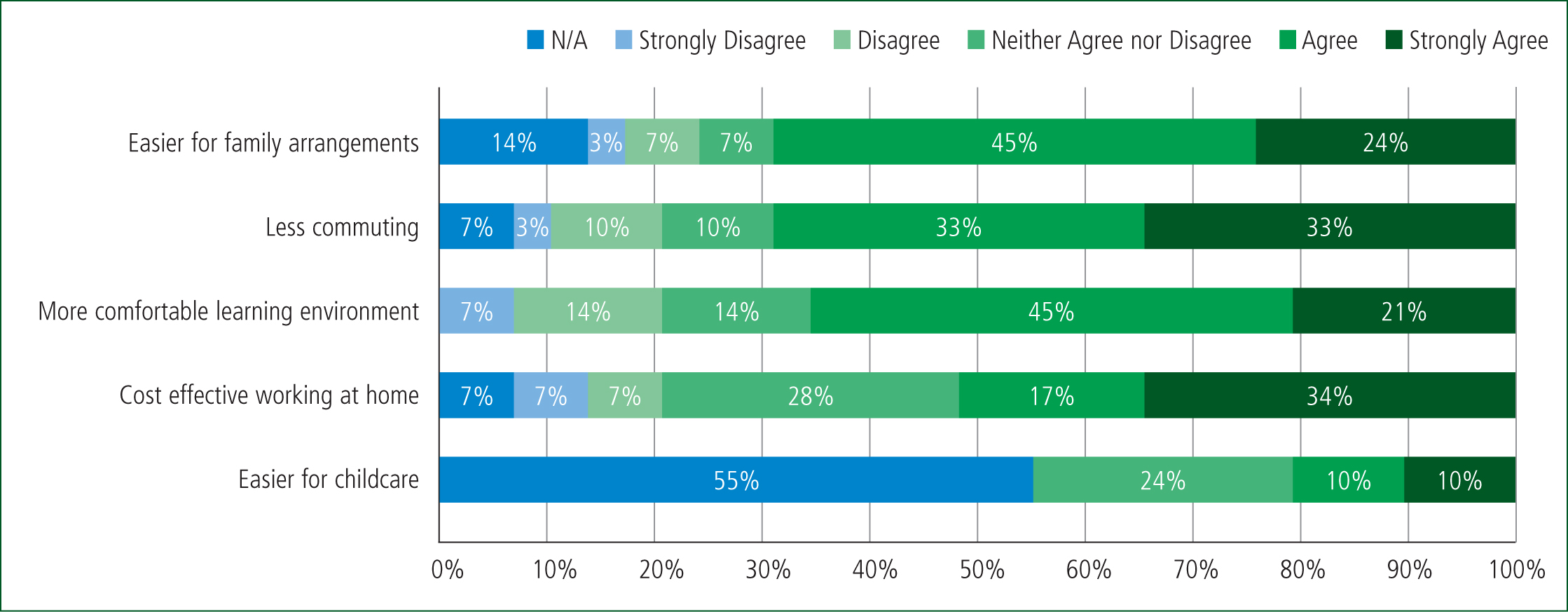

Figure 2 illustrates the benefits of learning at home during the lockdown. A significant portion of students (66%; n=19) reported that their home provided a more comfortable learning environment. Among those with family responsibilities, 69% (n=20) found that working from home made family arrangements easier. Additionally, 66% of students (n=19) agreed that online learning reduced the need to commute to the university.

Reduced time in simulation

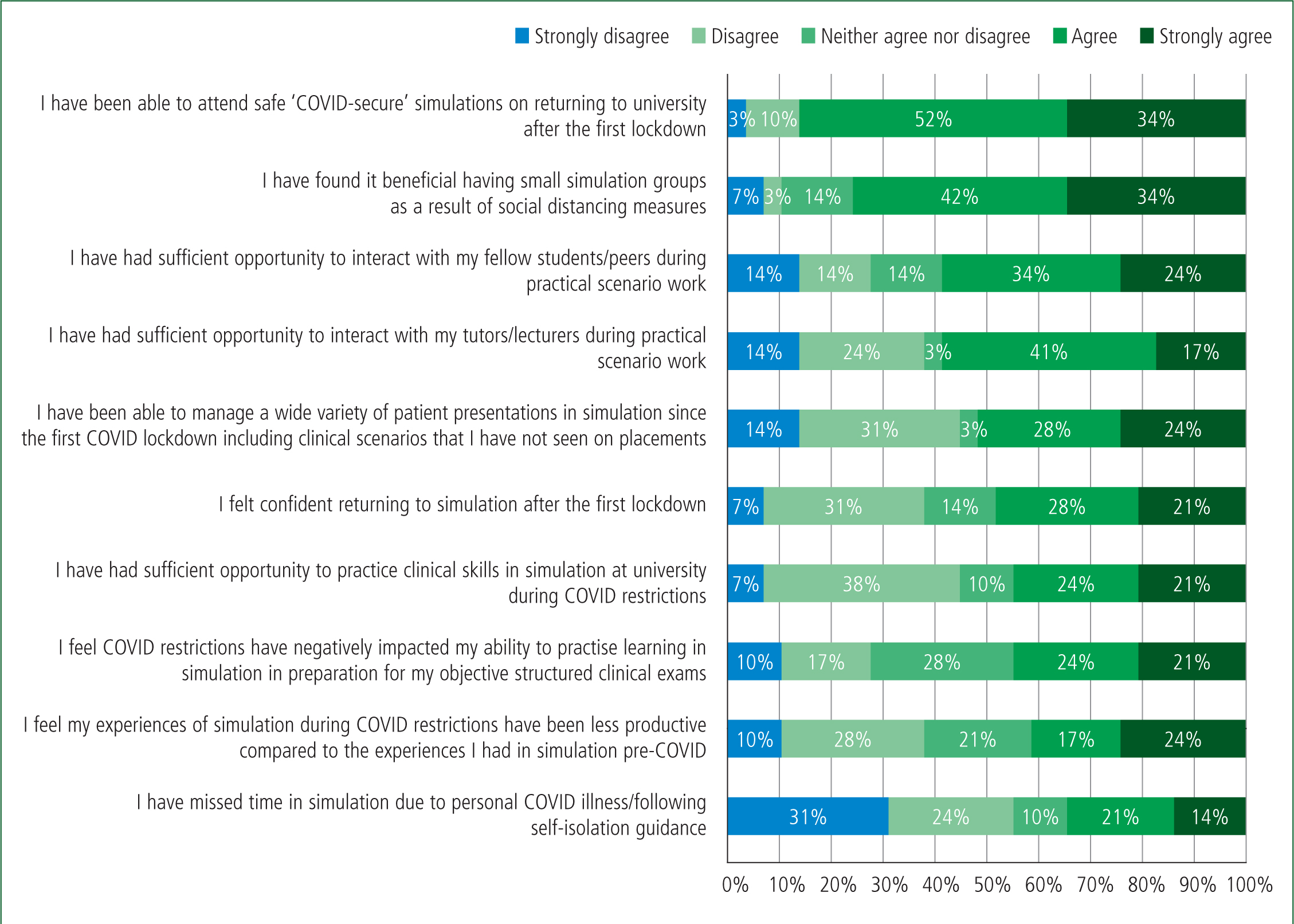

Upon returning to university after the first lockdown, a significant majority of students (86%; n=25) felt they had been able to attend safe ‘COVID-secure’ simulations (Figure 3). Twenty-two students (76%) found smaller simulation groups more beneficial during social distancing measures.

However, difficulties remained, as 12 (41%) felt less productive in simulation compared to pre-COVID experiences.

Cancelled clinical placements

Because of the COVID-19 restrictions, 79% (n=23) of student paramedics had their clinical ambulance placements cancelled. These placements are crucial for obtaining the required practice hours and educational elements necessary to pass the module.

Among the students affected:

No students were unable to return to placements after lockdown for shielding or personal reasons.

The limited flexibility of hospitals and other NHS agencies affected specialist placements in theatres and maternity wards. A total of 86% (n=25) students reported having one or more specialist placements cancelled, while 10% (n=3) were still able to attend them.

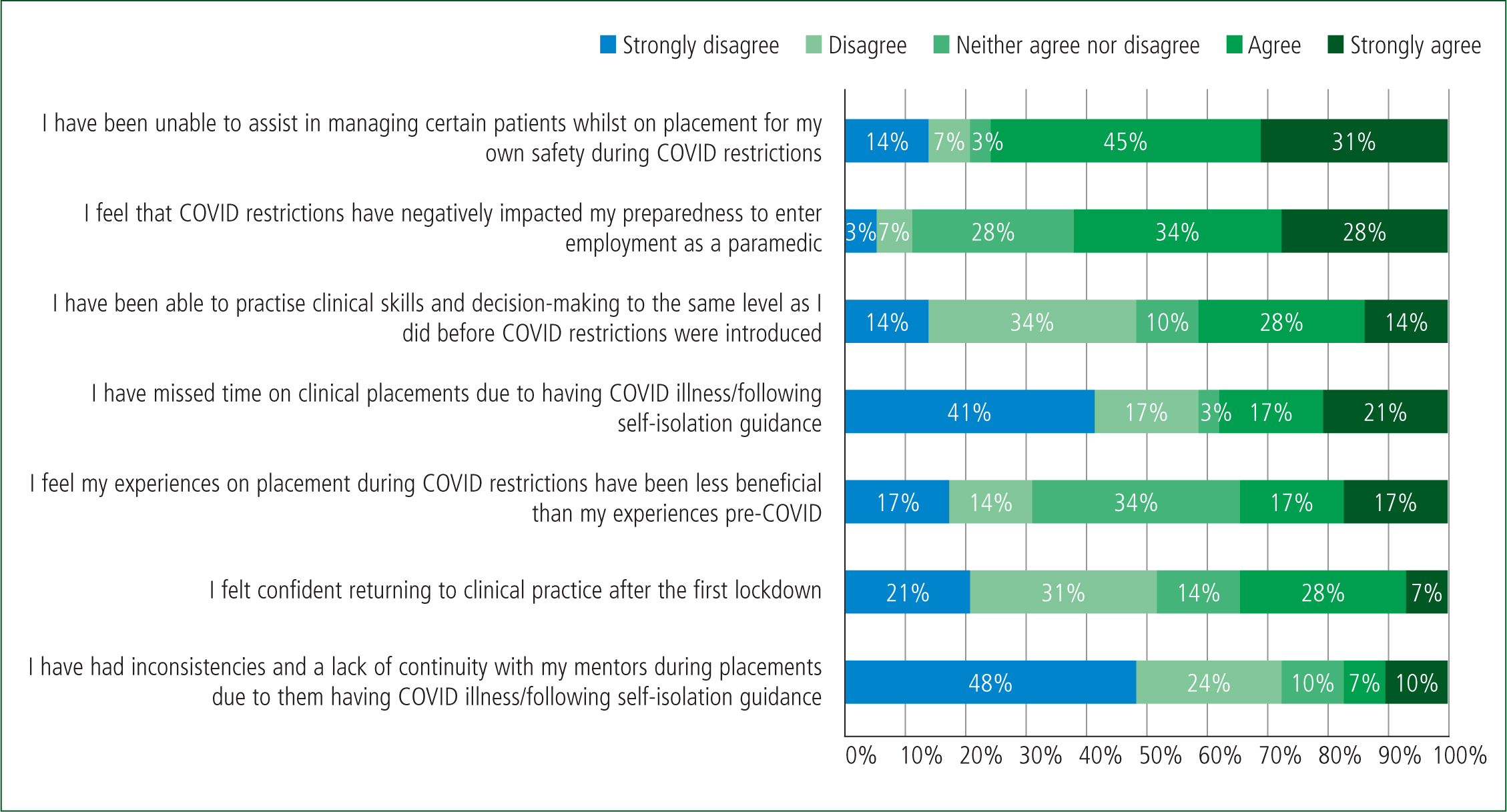

Figure 4 presents a 100% stacked bar chart summarising students' responses about their placement experiences during the pandemic. Safety concerns prevented 76% (n=22) from assisting in managing certain patients while on placement. Despite these limitations, 72% (n=22) were able to continue working with the same paramedic mentor. Of the participants, 38% (n=11) reported being required to self-isolate during their placement.

Regarding professional development, 62% (n=18) of students believed that COVID-19 restrictions negatively impacted their preparedness to enter employment as paramedics. In contrast, 34% (n=10) perceived no difference between their ambulance placement experiences before and after COVID-19 restrictions. Additionally, 52% (n=15) felt less confident returning to practice after the first lockdown.

Discussion

This research has similarities with Whitfield et al's (2021) paramedic study, particularly around the impact on clinical placements, online learning and simulation. As Hall et al (2020) highlighted, this absence of simulation as a mechanism for supporting students reinforces Abelsson et al's (2014) idea that simulation opportunities are highly beneficial for increasing confidence during paramedic education.

Nearly four out or 10 (38%; n=11) of students stated their confidence had been impacted by the reduced amount of time spent in simulation during COVID-19 and 45% (n=13) felt underprepared for their practical exams. As a result, these individuals were left lacking in confidence or feeling that they were underperforming, which negatively impacts their educational experience.

Providing practical sessions not only benefits education but also supports student welfare. Social interaction and a change of environment were issues during COVID-19, yet 58% (n=17) believe they had sufficient opportunity to interact with both their tutors and their peers on campus after lockdowns. Universities were successful in delivering COVID-secure simulations for smaller groups and this noticeably had a positive impact on 76% (n=22) of students in the study, who believed that smaller simulation groups of six were beneficial and this should continue in current education. In summary, there is an overall positive trend seen for ‘Reduced time in simulation’ in comparison to the other two sections.

The ‘Online learning’ theme had more negative implications. Farley et al (2013) reported that students described a decreased level of attention during online lectures, which correlates with 76% (n=22) of students who felt less motivated learning online compared to in person. An absence of directed learning and resource allocation may be responsible here, owing to the immediate and unexpected nature of COVID-19 restrictions initially.

Meanwhile, 66% (n=19) agreed that comfortable, remote working conditions and less commuting make home learning beneficial, as was also acknowledged by Pather et al (2020). However, 17% (n=5) of students felt isolated at home during lockdown, after being unable to interact with their peers outside lectures.

Additionally, 69% (n=20) felt that the universities could have done more to support the balance between their mental health and the workload, suggesting their welfare was negatively impacted from being isolated at home. Reinforcing mental health resources during online learning and encouraging educational and moral resilience frameworks in future teaching should allow institutions to better support students at home (Coyle et al, 2021; Defeyter et al, 2021; Wald and Monteverde, 2021).

Videoconferencing technology allows students to turn off their cameras and microphones during sessions, which promotes distractions at home and students can become disengaged from lectures (Castelli and Sarvary, 2021). Around one in three (34%; n=10) of students reported they felt uncomfortable asking questions and participating in online sessions, and this may lead to students becoming detached and isolated from academia, with some of those who may not feel confident seeking additional support outside the learning environment. Isolation increases the divergence between students who are self-motivated and those who may be struggling with this, which is reflected in the data with 48% (n=14) saying they did not adapt well to learning online. It becomes more challenging for education providers to identify individuals who are having difficulties, so all students learning from home should be offered more opportunities to discuss welfare and academic support on a 1:1 basis to mitigate this impact.

With ‘Cancelling clinical placements’, 62% (n=18) of respondents agree COVID-19 restrictions have negatively impacted them feeling ready as a paramedic. Many studies highlight the enthusiasm of students undertaking clinical placements to encounter different clinical presentations and practise psychomotor skills (Michau et al, 2009; Negri et al, 2017). However, although some students fully completed their placement hours, 24% (n=7) were notably unable to obtain the relevant clinical elements of practice for the module. Efforts need to be made to ensure consistency between all graduates in their ability to practise.

The Newly Qualified Paramedic (NQP) programme aims to alleviate discrepancies in clinical practice during the first 2 years of employment, with mentored support from an experienced paramedic (NHS Employers, 2019). This should help to diminish some of the impact of COVID-19 restrictions on those who may not have had significant exposure to a variety of patients.

The decision to cancel clinical placements was taken to maintain student paramedic safety following government guidance and operational restrictions (Public Health England, 2020; Hubble et al, 2021). Some three out of four (76%; n=22) of respondents agreed that these restrictions affected their ability to manage certain patients, particularly during aerosol-generating procedures or the management of COVID-likely patients. While this would lead to a negative experience, safety should be paramount.

Paramedic students do not require a minimum number of placement hours, but undergraduates still require sufficient exposure to practical frontline experience to develop and meet professional standards (Health and Care Professions Council, 2023).

Another contributing factor to a positive experience of the individuals in the study includes consistencies with mentors. The majority (72%; n=21) were able to consolidate their learning through having one practice educator/mentor, thus minimising disruption to their development and progression.

Strengths and limitations

It is difficult to recommend changes to placement restrictions owing to the unforeseen circumstances of COVID-19, although there are students who still feel positive despite the challenges faced during lockdowns.

Research into the effects of COVID-19 on healthcare education was heavily focused on medical and nursing professions at the time of investigation, with literature now emerging around the effect on paramedics. Therefore, a key strength is how this cross-sectional study captured the opinions of a group of paramedic students studying during this period to help understand this unique moment from their perspective.

The use of Likert scale surveys limited the data richness of the available responses, which open-ended or free-text qualitative responses may have allowed. However, this study was limited to a master's project, where time and resources were less readily available. Additionally, the sample size was low, limiting the generalisability of findings to the broader population. Future research would benefit from exploring these responses in more depth or to see how this student group has adapted to working in their professional area.

Conclusion

COVID-19 did cause disruption to student paramedics surveyed within this study. The greatest impact found that students felt less motivated when learning online at home during lockdown compared with being at university. Students were also unable to manage certain patients during clinical placements for their own safety and had differences in placement hours. However, students did find smaller simulation groups beneficial on returning to university. As COVID-19 was a national emergency at the time, restrictions were necessary for student safety and lessons have been learned for future lockdowns in paramedic education.