Health promotion is increasingly being recognised as an integral skill in a broad range of health professions. This is largely a result of the impetus to move health services from the constrained resources of the acute care sector into the community. Paramedicine is one profession reflecting these changes as its occupational role and scope of practice have moved into the community setting in recent years (Chan et al, 2019; Agarwal et al, 2020; Shannon et al, 2022). This is particularly true in rural parts of Australia where paramedics have an integral role in the community, including in health education and promotion (McManamny et al, 2020; Spencer-Goodsir et al, 2022).

In line with changes in the role of paramedics, tertiary education organisations must ensure undergraduate student training reflects future practice, providing experiential learning in rapport building, communicating about mental health and taking blood pressure.

This research explored the learning afforded to paramedicine students conducting health promotion activities as a work-integrated educational activity. The outcomes of the research are anticipated to contribute to the understanding of the role of this type of activity in paramedicine students' learning, and to allow for quality improvement of future iterations of the programme.

Background

Rural parts of Australia hold significant opportunity for health promotion activities as there is a combination of substantial burden of disease with limited access to health services (Smith et al, 2022). Delivering these can, however, be complicated by the geographic dispersion of the population, which can make it difficult to access many individuals.

One solution is taking health promotion to rural events where large numbers of people congregate, as was demonstrated by Seaman et al (2021) when they delivered a health promotion activity at an agricultural field day event. They exemplified one way health professional students can contribute to and learn about health promotion in rural areas.

Building on this, the present study seeks to explore the learning afforded to students who conduct health promotion activities in a rural setting. Specifically, this research aimed to explore the learning afforded to undergraduate paramedicine students during a short-term health promotion activity.

To achieve this, a regional university partnered with the Australian Men's Shed Association, to deliver the health promotion activity, ‘Spanner in the Works?’, at one of Australia's largest agricultural events. Bringing health services into the community is essential for advancing rural health promotion in Australia (Smith et al, 2022). Connecting rural men with health promotion activities is also one way to address the needs of this subpopulation, who experience a broad range of barriers to accessing health services (Buckley and Lower, 2002) and are considered high risk in several health categories (Department of Health, 2019).

This health promotion activity was undertaken by undergraduate paramedicine students as part of a university subject that incorporated work-integrated learning. Paramedicine students were identified as an appropriate cohort for this activity because health promotion education is important for their profession and such work is in line with their curriculum.

In the first year of their paramedicine degree, students are given opportunities to learn about the professional role of a community paramedic, including skills such as therapeutic communication, empathy, attitude, confidentiality and patient safety.

Students expressed their interest in participating in the health promotion activity through an expression of interest process. In the month before the placement, students were invited to a preplacement briefing with supervisors, the principal researcher and Australian Men's Shed Association coordinators. The briefing involved education on the health promotion activity, practical information for the placement including site location and transport, supervision requirements, a brief on the research project and time for questions.

Over the course of the 3-day agricultural event, the students conducted assessments including blood pressure, waist circumference, mental wellness with the Kessler 10 Psychological Distress Scale (K10), body mass index, alcohol consumption and smoking. These assessments were used as a basis for a general health promotion discussion based on the recommendations of the Spanner in the Works? programme. Each measurement or assessment that the students conducted was recorded, with colour coding from green to red to clarify actions including when to consult a supervisor for further intervention or provide a referral, which addressed duty-of-care responsibilities.

The activity was conducted in a supervised setting with Australian Men's Shed Association staff and mental health, nursing and allied health professionals available to students as required. Over the course of the 3-day event, health discussions were undertaken with 433 people, with the majority being men.

Research questions

The aims of this research were to explore:

- What learning is afforded to paramedicine students through the provision of a short-term health promotion activity

- What attributes and practices can facilitate paramedicine students' learning during a short-term, rural, work-integrated learning experience.

Methods

This research used a case study approach based on the ECOUTER mind-mapping method (Murtagh et al, 2017) to capture the learning afforded to students through their engagement with health promotion and the attributes and practices that facilitated their learning.

Murtagh et al (2017) outlined the four stages of ECOUTER methodology: ‘Stage 1—engagement and knowledge exchange; stage 2—analysis of mind map contributions; stage 3—development of a conceptual schema (a map of concepts and their relationships); and stage 4—iterative feedback, refinement and development of recommendations where appropriate.’

This method was deemed appropriate because of the non-sensitive nature of the data being collected (learning experiences) and the ability of a focus group to encourage participants to contribute and share. This method also allowed those taking part to reflect on each other's learning experiences and whether these aligned with their own.

Participants, recruitment and consent

All undergraduate paramedicine students who took part in the health promotion activity at the agricultural event in 2022 were invited to take part in the research. The principal investigator emailed the students an invitation with a copy of the participant information sheet, consent form and mind-mapping instructions for the focus group. Students were able to take part in the health promotion activity without participating in the research. They were encouraged to contact the principal investigator to ask any questions before attending the health promotion activity.

Consent and data collection were overseen by the principal investigator, who was independent of the supervision and coordination of the health promotion activity. To opt into the research, students were able to contact the principal investigator via email prior to the event or in person at the agricultural event. Consent for participation in this research was written and specific to this activity only.

Data collection

On the final day of the health promotion activity, the students who had consented to participate in the research attended an ECOUTER mind-mapping session facilitated by the principal researcher. This was hosted in a private tent at the field days site where the health promotion activity took place. Only two researchers (KC and EG) and the participants were present.

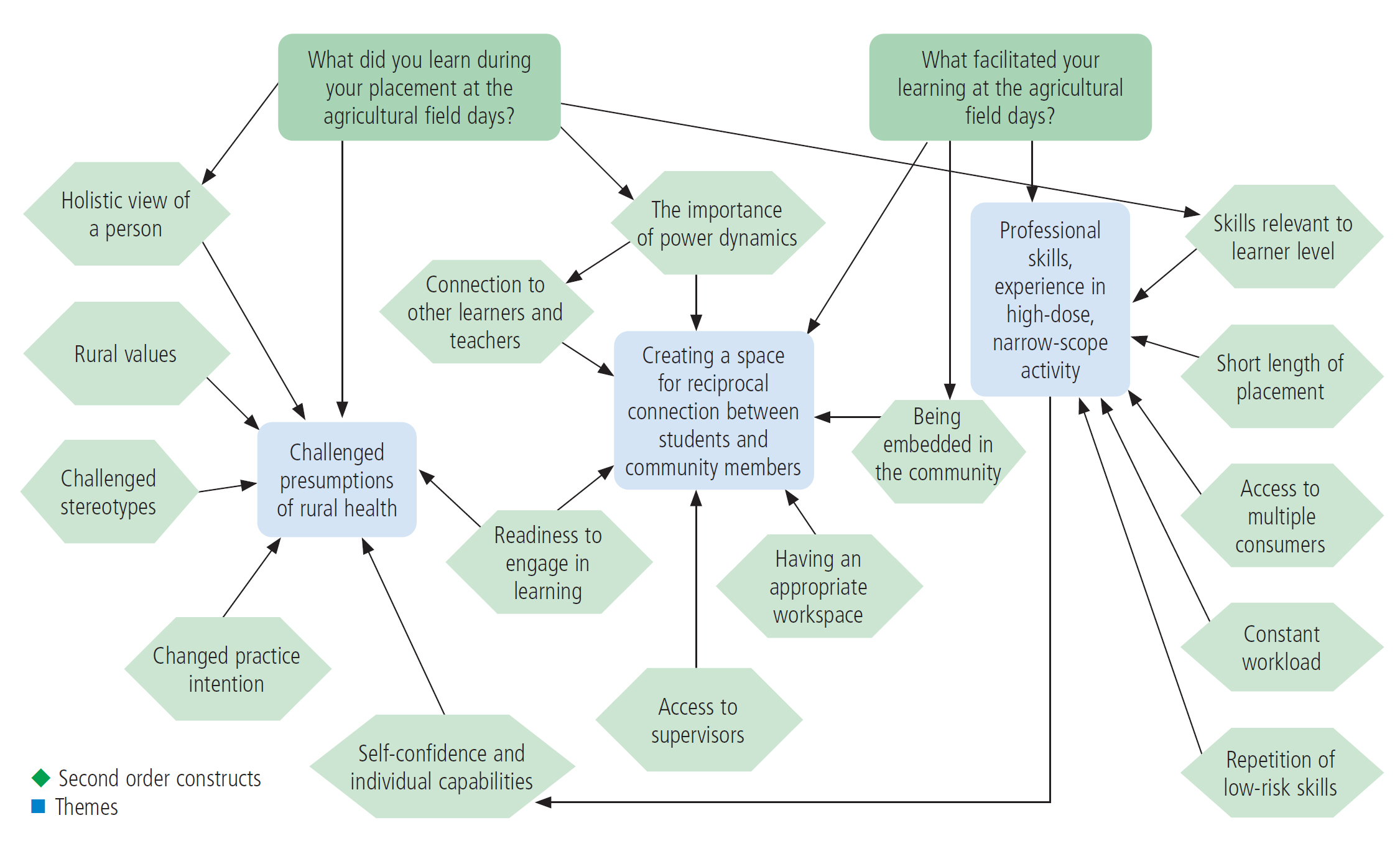

During the session, the participants were guided through the process of contributing to a virtual mind map using their mobile phones or iPads provided by the researchers. The virtual mind map was set up using Padlet, an online educational tool for organising and sharing content by means of virtual bulletin boards. The Padlet activity, moderated by the principal researcher, posed two central questions: ‘What did you learn during your placement at the agricultural field days?’ and ‘What facilitated your learning at the agricultural field days?’ The students gave written answers to the questions using the virtual mind map.

During this session, the principal investigator also prompted the students to reflect on how they learned and from whom. Reflections were recorded on the virtual mind map by the second researcher (EG).

At the end of the session, the principal investigator summarised and clarified contributions. The participants were informed that the link to the virtual mind map would remain open for a further 7 days so they could make any amendments or additions. During this time, the principal researcher continued to monitor contributions and remove identifiers.

Data analysis

Once the virtual mind map link had been closed, two of the researchers (KC and EG) conducted content analysis on the participants' contributions (first order constructs). An inductive approach to content analysis using the phases suggested by Erlingsson and Brysiewicz (2017) was taken.

The two researchers then discussed and reached agreement on top-level themes and sub-themes (second order constructs) using a constant comparative method, which were represented as a conceptual schema. The principal researcher emailed the conceptual schema to the participants so that they could make further comments.

Participants were invited to a second focus group to review the conceptual schema and provide feedback and additions. The students had been informed of the scheduled second focus group when attending the first one, and reminders were sent by the principal researcher via email in the weeks and days leading up to it. Despite this, no participants opted to attend the second focus group and, as part of the research process, it was not deemed ethical to require a reason for non-participation.

No further feedback was received from participants once the conceptual schema had been drafted.

Results

Of the 14 students who completed the health promotion activity, 13 opted in and consented to participate in the focus group. All were first-year students on a three-year bachelor of paramedicine degree at a regional university. To protect confidentiality, no further demographic information was collected.

Three main themes were identified from the focus group data:

- Practising professional skills through high-dose, narrow-scope activity

- Creating a space for reciprocal connection between students and community members

- Challenged presumptions of rural health.

Figure 1 displays the conceptual schema; it includes the first and second order constructs (themes) that were collaboratively agreed upon in the content analysis. The three main themes are discussed below.

Practising professional skills experience in high-dose, narrow-scope activity

This emphasised how the repeated and continuous structure of the health promotion discussions allowed students to hone their communication and clinical skills rapidly and efficiently. Students reported the significant advantage of practising key foundational skills in this way and emphasised the importance of their clinical and communication skills:

‘Practise building rapport and communicate effectively.’

Overall, this was reported as relevant to their future practice; it involved, for example, exposure to practising in a busy and loud environment, which will be a constant factor they will have to manage throughout their paramedic careers.

Creating a space for reciprocal connection between students and community members

This spoke to the importance of an empathetic approach and the sincerity of the students:

‘People can open up so easily based on your attitude towards them.’

Students felt they were in privileged positions hearing personal stories. These were described as ‘raw and meaningful’, and included both the victories and struggles of rural life:

‘I enjoyed how close the interactions were with the patients.’

Embedding the health promotion activity into a rural event was vital for shifting power dynamics. It enabled the students to create a strong connection with people attending the event. It created a safe space in a familiar and non-clinical environment, and also allowed the community to welcome t he students:

‘People were willing to come in just to give us practice.’

Challenged presumptions of rural health

This revealed an increase in confidence and trust in students' own professional skills, changes in personal perspectives, and shock and surprise at the mental ill health people disclosed:

‘Surprised about how many people were struggling with mental health.’

Mental health was a reoccurring theme:

‘I have been able to see the effects of mental health and how important it is.’

‘An eye-opener.’

Intentions to work in rural practice were seeded or solidified after the experience:

‘I considered rural placement when I hadn't before.’

‘The placement has made me interested in rural health practice.’

Furthermore, many had a change in perception of what a rural career would look like:

‘The placement was different to how I perceived rural health.’

Discussion

Health promotion activities such as the ‘Spanner in the Works?’ programme are often used as a strategy to engage men in their health at events and social settings (Alston and Hall, 2001; Moffatt et al, 2010; Seaman et al, 2021).

Involvement of paramedicine students in primary care activities such as health promotion aligns with the changing scope of practice of paramedics. These professionals are increasingly moving into more community and health promotion roles (Smart 2009; Chong et al, 2022). Health promotion is increasingly recognised as an activity in which paramedics should be involved to promote positive health engagement and behaviours (Schofield and McClean, 2022), especially in rural and remote locations (McManamny et al, 2020). Community paramedicine roles are being developed internationally to increase access to healthcare for rural communities outside emergency care and hospital settings (Choi et al, 2016; Martin et al, 2016; Patterson et al, 2016; Spencer-Goodsir et al, 2022). Experiences and exposure to these aspects of the evolution in scope of practice are important during students' foundational years to best prepare them for the realities of practice.

The benefits of involving students in health promotion activities and the impact of this on their learning is starting to emerge within the literature. Research examining the impact of health promotion activities through experiential learning has also shown positive outcomes for the students involved in them. Chong et al (2022) reported that student involvement in a health promotion activity allowed them to learn in a self-directed and collaborative manner, enabling them to achieve the required competencies during the experience. Comparable with the findings from this research, Chong et al (2022) found students were able to safely ‘experiment’ and apply their knowledge and engage individuals in health promotion while under supervision. Using experiential learning and authentic assessments supports students to become competent health promotion practitioners and prepares them for the community-based roles that are evolving in healthcare (Smart, 2009; Chong et al, 2022).

Reflecting on the results of the present study, the authors believe that what made this activity particularly effective for learning was its high-dose, narrow-scope nature and design. It included repetition of low-risk skills within the students' scope of practice and level of learning, such as measuring blood pressure, communication regarding assessments and building rapport with patients. The low-risk activities undertaken in this health promotion activity are consistent with those of other programmes conducted in Australia (Alston and Hall, 2001; Moffatt et al, 2010).

Effective learning was also supported through the creation of a space for reciprocal connection where students felt autonomous yet supported through the placement design and clinical supervision provided. Likewise, the community members participating in the health promotion activity felt safe to do so, exposing the students to an experience authentic to future practice. Those attending the event were willing to engage in the activity as they valued the contribution their involvement made to students' experience and the learning resulting from it. They were motivated to engage when they told they had the opportunity to contribute to the students' learning and this seemed to attract them to be involved. The health promotion activity was of mutual value to people attending the field days and students, reflecting ‘health promotion values such as empowerment, equity and community participation’ (Chong et al, 2022).

The design of the health promotion activity resulted in students taking a more holistic view of community members and realising ‘the importance of a holistic biopsychosocial assessment’ (Shannon et al, 2022). They reflected on assumptions they had made before engaging in the activity, and this led to unanticipated changes in perception which were deemed to be transformational for their future practice intentions.

This was particularly evident regarding conducting mental health assessments, which exposed students to new educational experiences. While this learning challenged students, it left them with new knowledge, skills and empathy, increasing their feelings of capability in this aspect of practice.

Health promotion activities such as these provide a service to rural communities and immersive learning experiences for health students. This type of activity could be replicated at other events and is worthy of further research exploring reach and impact.

Limitations

This research focused on a small group (n=13) of paramedicine students from a regional university so may not be representative of learning experiences of other cohorts of students. Selfnomination of students to attend this placement may present a positive bias towards this type of activity, resulting in the students reflecting favourably on their learning.

The results of the research were not subject to member checking despite the researchers' attempts to engage the participants in follow-up. Limited participation in the second focus group may have been mitigated by researchers attempting different modes of follow-up such as phone calls or text messages.

The results are representative only of the short-term effects of learning and immediate practical experience; long-term follow-up was not conducted.

This research also focuses on only the perspectives of students undertaking the health promotion activity so does not reflect the impact of providing this service on the community.

Conclusion

This research adds to the literature demonstrating the efficacy of health promotion activities in the student learning experience.

The results suggest that learnings afforded to students in this innovative placement model are influenced by bringing health services to the community to create a reciprocal connection between student and community members and a high dose and narrow scope of professional skills practice, which expanded students' understanding of rural and mental health and challenged presumptions around rural health.

These findings demonstrate the value of short health promotion activities for paramedicine students and their future practice, particularly regarding their intention towards rural health practice.

Key Points

- Health promotion activities make a significant contribution to rural communities and immersive learning experiences for health students

- Innovative, short-term placements provide valuable learning opportunities

- Learnings afforded to students from this model are represented in three main themes: professional skills experience in high-dose, narrow-scope activity; creating a space for reciprocal connection between students and community members; and challenged presumptions of rural health

- Attending a rural placement influences students' intentions regarding working in rural health practice

CPD Reflection Questions

- Why target first-year undergraduate paramedicine students for a short-term placement at a health promotion activity? How does this fit with the role of a paramedic in the community?

- What can paramedicine students learn in a short-term placement?

- What are the benefits of collaborating with a community organisation to provide a health promotion activity?