Despite heat illness being written about for thousands of years, it remains a cause of death. Recent heatwaves have been estimated to have been associated with over 3000 excess deaths a year in the UK (Office for National Statistics, 2022) and tens of thousands of deaths worldwide (World Health Organization, 2018). Furthermore, heat-related deaths are predicted to more than double in the next 30 years (Hajat et al, 2014).

Heat illnesses are a spectrum of diseases where heat production exceeds the rate of heat loss so that the core temperature rises. The illness can vary in severity from heat cramps and heat rash (miliaria rubra), progressing to the more severe heat exhaustion and heatstroke (Gauer and Meyers, 2019).

Heatstroke is a life-threatening disorder, usually defined by a core body temperature greater than 40°C with central nervous system (CNS) dysfunction, such as delirium, seizures and coma (Bouchama and Knochel, 2022). This is described as classical when it results from exposure to environmental heat or exertional such as occurs during strenuous exercise (Bouchama et al, 2022).

This article discusses what was known and has been written about heat illness over the centuries. It reveals the way in which treatments have gone in and out of fashion, and how our understanding has developed and been refined—albeit with some detours—over the years.

Heat illness over the centuries

Heat-related illnesses have been documented and treated since written historical records began. Various synonyms have been used through the ages, including sunstroke, siriasis, thermic fever, ardent fever, heat apoplexy and heat exhaustion (Casa et al, 2010).

Classical antiquity

Mentions of siriasis can be traced back to ancient times. In ancient astrology, Sirius (from the Greek for scorching) referred to the brightest star of the constellation, Canis Major (Latin for ‘big dog’), which marked the hottest part of summer in the Northern Hemisphere (Theodosiou et al, 2011). Although the ‘dog days’ of summer were recognised by the Romans, the realisation of the dangers of heat illness first appeared in the Greek poet Homer's ‘Iliad’ (8th century BC) (Homer, 1991):

‘Blazing like the star that rears at harvest, flaming up in its brilliance…that star they call Orion's Dog—brightest of all but a fatal sign emblazoned on the heavens, it brings such killing fever down on wretched men.’

Heat-related illnesses are mentioned in the Bible. In the Book of Judith, written in the 6th century BC, Judith's husband, Manasseh ‘suffered heat stroke while he was overseeing the workers in the fields and died…’ (The Holy Bible, 2011). Biblical scholars have suggested another passage that might allude to heatstroke when a child developed a pain in his head after being exposed in the field during harvest season and died in his mother's arms (The Holy Bible, 1983a). The risks of the sun and heat are also recognised in the book of Isaiah:

‘They will neither hunger nor thirst, nor will the desert heat or the sun beat down on them’.

A century or so later, during the classical period (4th and 5th centuries BC), the Greek physician and ‘Father of Medicine’, Hippocrates, also described how ‘excess of heat induced debility of the muscular fibre, impotence of nerve, torpor of mind, haemorrhage, fainting, and, lastly, death’ (Hippocrates, 2015).

Around the same time, the Greek historians and authors, Herodotus and Thucydides, documented the dangers of exposure to heat. Herodotus wrote nine books, which provide much detail about the life and events of the Persian empire, which is now modern Eastern Europe, West Asia and North-West Europe. In Book VI of Herodotus' Histories, the Ionians (Greeks), in preparation for a Persian invasion, were ‘unaccustomed to such toils and being exhausted with hard work and hot sun’ and many had ‘fallen into sicknesses’ (Herodotus, 2018). Another example is found in Book VI, which describes the Battle of Marathon in 490 BC, the first attempted Persian invasion of Greece. The Athenians sent a herald named Philippides to run from Athens to Sparta to recruit reinforcements, a distance of about 240 km, completing the journey the next day (Herodotus, 2018). Philippides announced the victory at Marathon to the magistrates in Athens, before he then died (Lucian, 1959) (Figure 1). The modern-day marathon is based on these events.

Thucydides wrote in his account of the Peloponnesian war between the cities of Athens and Lacedaemon (Sparta) about the dangers of battle in the heat of the sun (Thucydides, 1914):

‘Crowded in a narrow hole, without any roof to cover them, the heat of the sun and the stifling closeness of the air tormented them during the day, and then the nights, which came on autumnal and chilly, made them ill by the violence of the change; … while hunger and thirst never ceased to afflict them.’

The risks of heatstroke in warfare remained throughout the conquests of Alexander the Great. His conquests between 336 and 323 BC to establish the Persian empire, the largest in the ancient world (Figure 2), meant that his soldiers were ‘fatiguing on account of the excessive heat’ and ‘the entire army was seized with thirst’ (Arrian of Nicomedia, 1883). On his return to Babylon, crossing through the Gedrosian desert, he lost three-quarters of his soldiers, probably due to the scorching heat and lack of water (Arrian of Nicomedia, 1883; Dryden et al, 2004).

Three hundred years on, heat-related illnesses continued to inflict damage on military campaigns. In 24 BC, Aelius Gallus, a Roman governor of Egypt, entered Arabia Felix (South Arabia). According to the Roman senator and historian Dio Cassius, Gallus' army (Jarcho, 1967), they:

‘did not proceed without difficulty; for the desert, the sun, and the water (which had some peculiar nature) all caused his men great distress, so that the larger part of the army perished. The malady proved to be unlike any of the common complaints, but attacked the head and caused it to become parched, killing forthwith most of those who were attacked.’

Galen of Pergamon (c130 AD to c210 AD), one of the most influential medical authors of his time, devoted several treaties to understanding fever and began to differentiate heat-related fever as a separate illness: ‘the manner in which one is heated by standing in the sun, or in front of a fire, is different from that in which one is heated by drugs’ (Galen, 1997). He also noted that ‘people who spend an excessive amount of time in the sun in summer are subsequently dried out, their entire bodies become dry…and they suffer intolerable thirst’ (Galen, 1997).

Medieval era to the Renaissance

Into the Middle Ages, several eminent figures emerged, building upon knowledge acquired during the classical period.

Avicenna, a Persian physician in the late 10th century, expanded upon the works of Hippocrates and Galen in his 14-volume book (Smith, 1980). He described some of the features of heat illness, namely sweating, asthenia (fatigue), oliguria, thirst and muscle weakness (Avicenna, 1973). He further understood the effect of the environment on heat-related illness (Avicenna, 1973):

‘That there are definite extracorporeal influences on the metabolic working of the human body should now be intelligible. The effect of heat, cold, wet climate, dry climate is well enough known but is widely ignored.’

At this time, over 50 different types of fever were recognised; there was an understanding of both exertional and classical heat illness and its mechanisms (Muñoz and Irueste, 2005). Isaac Judaeus, a prominent Egyptian-Jewish physician, proposed that the mechanism for fever after excessive exercise was a disruption of the natural spirit, causing organs, muscles and nerves to get too hot and, ultimately, this heat would rise to the brain ‘taking possession of it and confusing it’ (Muñoz and Irueste, 2005), a comment on the neurological dysfunction that occurs with heatstroke. Meanwhile the fever from excessive heat produced ‘a great effervescence in the blood, which affected the brain, the “seat of the psychic spirit”’ (Muñoz and Irueste, 2005).

This separation into heatstroke due to excessive heat and excessive exercise was continued by Bernard de Gordon (1270–1330 AD), a medieval physician from Montpellier. He also had insights into the mechanisms: he argued it was in the skin, not the blood, where the heat damage occurred. Obstruction of the pores prevented the release of heat from the ‘hot and dry gases’, causing the body to ‘heat up excessively and give the appearance of fever’ (Muñoz and Irueste, 2005).

Some understanding of the mechanisms around this time however were different to our current understanding: several medieval physicians, including Gilbetus, Gordon and Avenzoar, still attributed heat illness to red or yellow bile inside the vessels of the heart, lungs, stomach or liver (Handerson, 1918; Muñoz and Irueste, 2005).

The Age of Enlightenment to the Modern Era

Over more recent centuries, heat illnesses have continued to be described and classified, but are hampered by the many different terms in use and case reports rather than systematic reports.

The term ‘causus fever’, used by Hippocrates, can be translated as ‘ardent fever’; both terms seem to indicate severe heat illness (Yeo, 2005). Herman Boerhaave, the Dutch physician (1715 AD) who also put his name to rupture of the oesophagus after vomiting, argued that ardent fever ‘deserves to be separately treated of, because of its frequency, danger, and difficulty to cure’ (Swieten and Boerhaave, 1765). He attributed several causes including ‘too hard labour, over-walking, the heat of the sun long sustained and received on the head chiefly…the use of heating’ (Swieten and Boerhaave, 1765). He also listed neurological features including delirium, phrenzy and convulsions associated with ardent fever (Swieten and Boerhaave, 1765), accepted as part of the current definition of heatstroke.

Both the French physician Du Port and Boerhaave also described ‘ephemeral fever’, which can be caused by the heat of the sun or exertion, but also by anxiety, apprehension, and anger (Du Port, 1988). This was considered less severe and at the milder end of the heat-related illness spectrum than ardent fever (Swieten and Boerhaave, 1765):

In an ephemera, or simple fever of a day's continuance, there is a moderate heat; however, in an ardent fever, an intolerable burning heat destroys the body.

In 1775, George Motherby's, A New Medical Dictionary, describes other synonyms for heat illness, including ictus solaris, insolatio, and coup de soleil (Motherby, 1775). These were disorders that arose from excessive heat from the sun or the effects of culinary fire (Motherby, 1775).

In Remarks on Sunstroke, the American physician, James J Levick, claimed that there was little written on the subject of sunstroke because it only occurred infrequently in England and that it was sometimes misdiagnosed as such conditions as apoplexy, acute congestion, and cerebral inflammation (Levick, 1859). Apoplexy (from the Greek apoplexia meaning ‘to strike suddenly’) can be traced back to classical antiquity and referred to a sudden loss of consciousness followed by sudden death (Engelhardt, 2017). Attempts to differentiate sunstroke from apoplexy were not always successful, even into the 1850s (Spellissy, 1902). However, the term became obsolete by the 19th century, by which time the true cause could be more accurately diagnosed (Engelhardt, 2017).

As for heatstroke in cooler climates such as the UK, more knowledge of the disease came from the expansion of the British Empire into India, the West Indies, North America and Africa (Bynum, 1981), as seen by the increase in publications on the topic in prominent medical journals. These were largely the works of physicians and surgeons serving abroad ‘where its effects are so fearfully felt’ (Levick, 1859). Scottish Royal Naval surgeon, James Lind, reported (Lind, 1811; Bynum, 1981):

‘In those countries [with a hot climate], soldiers, during fatiguing marches, while sweating under the oppressive load of arms and warm clothing, are apt, in the heat of the day, to be suddenly seized with a species of apoplexy.’

Similarly, Napoleon's chief surgeon, Dominique Jean Larrey, reported ‘great suffering, from the excessive heat of the weather’ in Spain (Larrey and Hall, 1814) and described the scorching sun of Egypt, where even ‘the most vigorous soldiers, parched with thirst and overcome by heat, sunk under the weight of their arms’ (Larrey and Hall, 1814).

In a presentation to the Royal Society of Medicine in 1935, Douglas HK Lee (1935) accurately described physiological reactions to heat including hyperpyrexia, cardiovascular collapse, electrolyte imbalance and super-dehydration; he also split heat illness into four distinct but overlapping clinical syndromes very similar to current classifications:

- True heat stroke

- Heat exhaustion

- Heat cramps

- Dehydration.

Around this time, risk factors were beginning to be defined. Men who were overweight, older and newly recruited were most at risk, while training activities, season and nutrition significantly influenced the incidence rate (Goldman, 2010). The war efforts culminated in the publication of an authoritative and landmark book titled, Physiology of Man in the Desert, where Adolph (1947) compiled enormous volumes of experimental data on heat, exercise and dehydration. Leithead and Lind (1965) produced a textbook titled, Heat Stress and Heat Disorders, covering heat physiology (part I) and heat disorders (part II), another authoritative and landmark textbook.

Treatments of heat illness

Water as a treatment for heat illness has featured heavily over the centuries. Other treatments have been in and out of fashion.

Prevention

Preventative medicine has been attributed to Hippocrates. The revised Hippocratic Oath, familiar to graduating doctors, includes the line (Hajar, 2017):

‘I will prevent disease whenever I can, for prevention is preferable to cure’.

Measures to prevent heat illness can be found in the writings of Herodotus. He noted that the Ionians, following 7 days of exhausting labour in the hot sun, ‘kept in the shade, and would not go on board their ships or practice any exercises’ (Herodotus, 2018). Hippocrates (1943) and Galen (1998) also urged caution in exercising in the summer to ‘avoid overheating as much as possible’.

Medieval folklore contains descriptions of preventative measures: the mythical Slavic character Poludnitsa (or Lady Midday), a young woman with a scythe, is said to have roamed the fields in the middle of hot summer days, questioning those who were working rather than resting (Dixon-Kennedy, 1998). If anyone answered unsatisfactorily, punishment included headache, neck twisting and sudden death (MacCulloch et al, 1916), prompting workers to avoid labour during the hottest part of the day.

A paragraph published in the British Medical Journal (1872) under the title of ‘Coup De Soleil’ concluded: ‘That “precaution is better than cure” is no doubt a stale and trite proverb; but in this [heat stroke], as in many other instances, it is as true as it is trite’, indicating how Herodotus' advice remains true today.

Water therapy

Ancient times to the 19th century

The earliest use of water as a treatment for heat illness appeared within the works of Herodotus (2018), around 450 BC, describing the Indian tribes who would ‘drench themselves with water’ when the day was at its hottest.

There has been, however, much concern about the use of cold water over the years. Hippocrates also knew of the cooling effects of water but noted that cold water could provoke convulsions, spasms and febrile chills (Hippocrates, 1943). He therefore advised that ‘if a patient suffers from a fever not caused by bile, a copious affusion of hot water over the head removes the fever’ (Hippocrates, 2021), believing that ‘after a warm affusion the body cools off, because it is more dilated, and after a cold affusion warms up, because it is more contracted’ (Hippocrates, 1943). Galen perpetuated this advice, suggesting that as those who spent ‘an excessive amount of time in the sun in summer’ would be both hot and dry, ‘the cure for them is ready to hand and very easy, not only if they drink but also if they bathe in warm, fresh waters’ (Galen, 2020). Specifically for heatstroke, he believed it was ‘necessary for you to add one bath to the two and bathe three times’ (Galen, 2011).

As well as using water on the skin to cool, much was made of drinking water and other liquids. According to Hippocrates (1943), cold water was good for patients if heated and cooled slightly. Around the 2nd or 3rd century AD, Galen (2018) promoted drinking cold water in moderation, but avoiding cold water sources that were stagnant, foul smelling or salty. When the fever was caused by the sun or by fasting and labouring, he also advised that ‘moistening nourishment is the greatest cure’ (Galen, 2011), such as Apomel, a mixture of honey and vinegar (Galen, 2018).

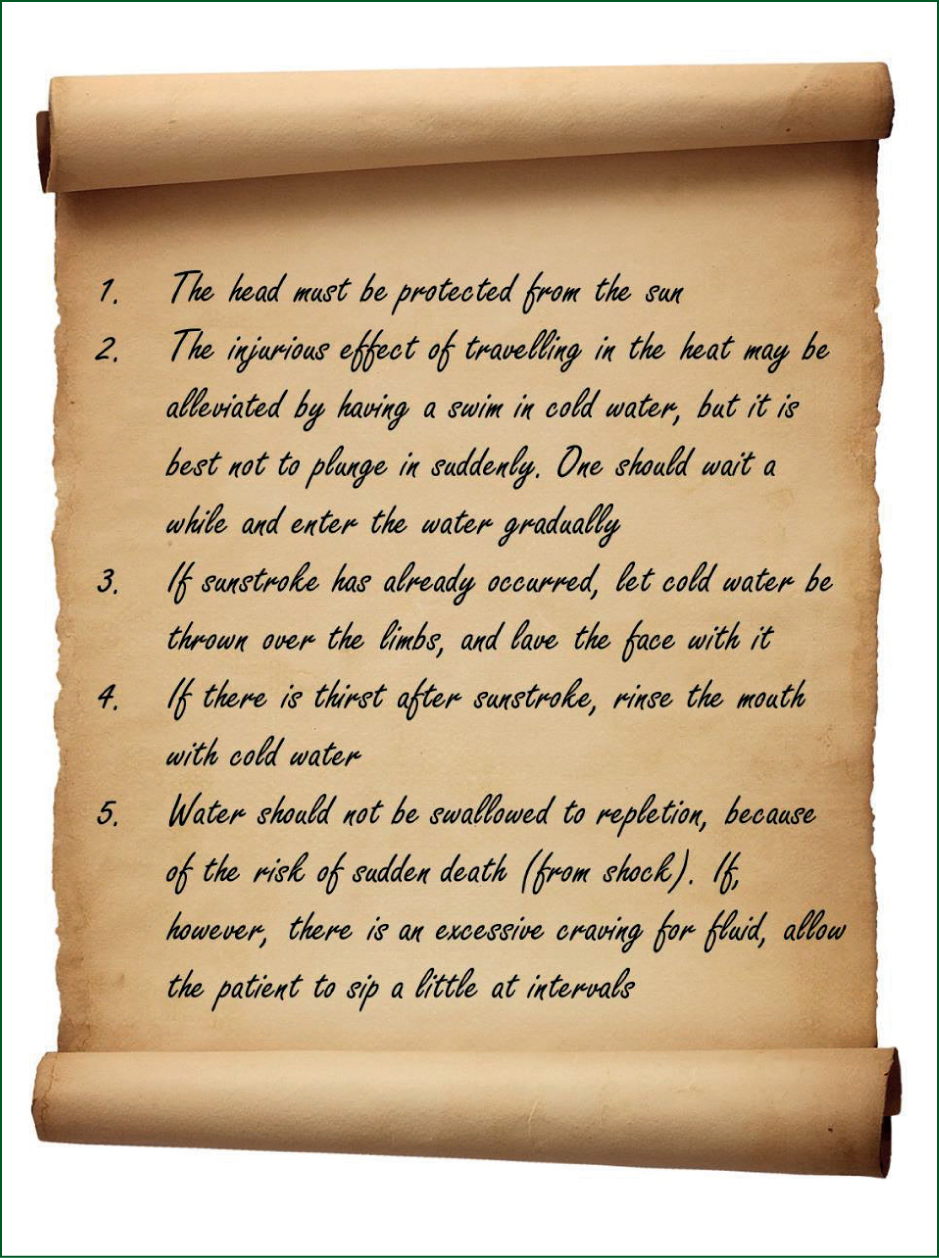

By the 11th century, Avicenna (1973) showed a clearer understanding of treating heat-related illness (Figure 3), many of which remain relevant today.

Fear of the effects of cold water in treating heat illness continued until Motherby (1775) in the 18th century. Benjamin Franklin, one of the Founding Fathers of the United States, also believed that: ‘to throw oneself into cold spring water, when the body has been heated in the sun, is an imprudence which may prove fatal’ (Pomeroy, 2021).

Similarly, the American physician and Founding Father, Benjamin Rush, writing in the 18th and early 19th century, described three cases where drinking cold water led to disease or death (Rush, 1830). The popular opinion at the time was that drinking large quantities of cold water by an extremely warm body was dangerous (Currie, 1805). Rush's works and concerns were influential, and in 1814, the Humane Society even posted cautions on public pumps warning about the risk of sudden death from drinking cold water (Spellissy, 1902).

Not everyone agreed that cold water was detrimental however. At the end of the 18th century, the Scottish physician, James Currie, argued that the deaths seen by Franklin and others were not the result of going into the cold water while being too hot but rather ‘when cooling, after having been heated’ (Currie, 1805), perhaps because of the risk of over-cooling. After extensive study of thermal physiology in humans, Currie (1805) advised: ‘if sweating has been brought on by violent exercise, the affusion of cold water on the naked body, or even immersion in the cold bath, may be hazarded with little risqué, and sometimes may be resorted to with great benefit’ noting ‘at such times, on applying the thermometer to the surface, the heat has been found suddenly and greatly reduced’.

19th century onwards

From around the middle of the 19th century, the benefits of using cold water to treat heat illness became more established, often based on military experience. Two key publications in 1859 in the Lancet and another in the Medical Times and Gazette confirmed a shift in attitudes towards cold water therapy, all from British surgeons serving overseas (Pirrie, 1859; Longhurst, 1860). G.S. Beatson, Surgeon General to the Indian Army, advised to treat heatstroke as follows (Levick, 1859):

‘…unfasten as quickly as possible the man's dress and accoutrements, to expose the neck and chest, get him under the shade of a bush, raise his head a little, and commence the affusion of cold water from a sheepskin bag, continuing the affusion, at intervals, over head, chest, and epigastrium, until consciousness and the power of swallowing returned.’

In the event the individual remained unconscious or showed no signs of life, Infantry Surgeon G. Barnard (1868) stated:

‘We must keep the circulation going at the same time that cold is applied’.

For those seemingly peri-arrest:

‘…the cold douche rapidly restores action before the circulatory system suffers materially; and though a man may have ceased to breath, reflex action is excited by the cooling of the douches, and respiratory movements return.’

Although most people in the mid-19th century had accepted the benefits of cold water affusions and hydration as cooling mechanisms, not all had. The 20th-century conflicts saw cold water therapy universally adopted for the treatment of heat illness, a practice that continues to this day.

Cooling agents

Aside from water, several cooling agents have been suggested throughout history, falling in and out of use.

One prominent oral cooling agent was alcohol. The use of wine among Hippocratic doctors is well documented including its use as a purgative and, if mixed with water, as a cooling recipe (Jouanna, 2012). It was advocated during the Roman campaign in Arabia Felix (24 BC):

‘There was no remedy for it except a mixture of olive oil and wine, both taken as a drink and used as an ointment’.

This concoction, with unknown efficacy, was not readily available; however, according to Galen (2011), diluted wine had coolant properties and was considered ‘better than water in all respects, combining to increase digestion and promote urination and sweating’. Therefore, ‘if it is summer and the place is naturally hot and stifling, or the climatic conditions are excessively hot, you must give the wine with cold water’ (Galen, 2011).

Over the years, opium, mandrake and hemlock, various oils (including those of roses, unripe olives (omotribes) (Galen, 2011), violets, water lilies and nightshade (Paré, 1649), deadly nightshade, and snow have been suggested as cooling agents (Avicenna, 1973). Proponents of opium continued for centuries: Benjamin Rush (1830) stated: ‘I know of but one certain remedy for this disease, and that is liquid laudanum’. However, John Watts Jr challenged that: ‘…laudanum was not a specific remedy, since no recovery was attributed to its sole influence’ (Spellissy, 1902) and ‘it may even be feared that some persons have fallen victims to the injudicious and extravagant administration of laudanum’ (Stevens, 1821).

Into the 17th century, the use of cooling clysters (enemas) gained traction. The British physician, Thomas Sydenham, reported that they ‘could quiet too great heat of the blood at pleasure only by the use of these’, and Boerrhave believed that they were the most efficacious remedy for cooling after bloodletting (Swieten and Boerhaave, 1765).

Levick (1859) was unconvinced that cold affusions would work for sunstroke, believing ‘instances in which the powers of life may be so spent, as to fail to respond to the shock of the cold, and the existing depression be thus increased’ warranted stimulants, of which ammonia enema was the most frequently used, although their effects in four cases were described as ‘very meagre’ (Spellissy, 1902).

Due to the various treatments adopted, it was unclear which treatment was the most effective. In the 19th century, physicians often advised multiple treatments simultaneously, such as ‘bloodletting, general and local cold applications to the head, cathartics, clysters, antimonials, rest, quiet, counterirritants, cordials, darkness, abstinence’ (Martin, 1859).

From Hippocrates to the Enlightenment, diseases were often thought to be due to disruption of natural equilibrium, which could be restored by using stimulating or depletive therapies. A 24-year-old soldier with sunstroke serving in the Benares State (India) in 1858 was successfully treated with medications given to stimulate the nervous centres and included ‘croton oil dropped upon the tongue; turpentine enema administers, and brandy-and-water given as indicated’ (Longhurst, 1860).

None of these treatments are currently advocated.

Bloodletting

Bloodletting is the removal of blood as a treatment for numerous diseases, including heat illness, and has been practised over many centuries. It is based on the idea of removing ‘humours’ from the body, thought to be the cause of the illness. It incorporates venesection, scarification, cupping and leeching.

The origin of this practice has been attributed to the Ancient Egyptians (Greenstone, 2010), where instruments for venesection have been found preserved in Egyptian sarcophagi (Stern, 1915) and inscribed on temples (Figure 4) (Coppens and Vymazalova, 2010). The practice had been established by the time of the ancient Greeks (Figure 5) as a means of balancing excess humors. Both Hippocrates and Galen advocated the practice and gave detailed advice on when it should be used (Brain, 1986). Galen (2011) advised to continue until the patient was at the point of fainting if there was a plethos of overheated blood but to be avoided in very hot weather.

Bloodletting was a common practice for many centuries. It was used by the Jews in the Mishnaic times (2nd to 3rd century AD) and was performed by a skilled artisan rather than a physician (Talmud, 2024).

In the Middle Ages, monasteries contained special facilities where venesection was performed by monks until church edicts forbade the practice (Amundsen, 1978; Brenner, 2020). One Abbot, Peter the Venerable (1156 AD), described his experience as a patient while suffering from catarrh. He had postponed his regular bloodletting due to concern with side effects but felt an ‘overabundance of blood and phlegm was bringing on a fever’ and finally had ‘large amounts of blood drawn off within three weeks’ (Siraisi, 2009).

Into the 16th century, prominent physicians were adherents of venesection. Boerhaave believed that for severe ardent fevers, ‘bleeding is of an absolute necessity’ but ‘great caution is necessary …’ (Swieten and Boerhaave, 1765). He observed that when a large amount of the blood has been removed, the heat of the body proportionably decreases (Swieten and Boerhaave, 1765).

By the late 18th century, bloodletting was deemed the core treatment of sunstroke:

‘First bleed as freely as the strength will admit’.

‘In one day, from a species of coup de soleil, she [the HMS Liverpool, Endymion-class frigate] lost three lieutenants and thirty men…The frigate's deck at one time resembled a slaughterhouse, so numerous were the bleeding patients’.

Not all physicians at the time were in favour of bloodletting however. The military surgeon Beatson (1846) regarded bloodletting in heatstroke as an ‘injudicious and injurious practice’ while William Pirrie (1859) commented ‘in no case was general bloodletting at all beneficial, but decidedly the reverse’.

Other methods to reduce blood volume were sometimes used. During the expedition by Lewis and Clark in 1804–1806 to explore land recently acquired by the United States, one man was given nitre, a diuretic, ‘which revived him much’ (Peck, 2002). James Ranald Martin (1859), another military surgeon in the 19th century, advocated the use of leeches behind the ears for less severe symptoms, unconvinced of the value of cold affusion as the chief means of cure.

Alternative treatments

In the 19th to 20th centuries, siriasis was believed by some to be caused by the radiation of the sun which ‘mandated wearing actinic orange underwear, a spine pad, and solar topee (a cork or pith helmet) to prevent these rays from penetrating to the brain and spinal cord’ (Pandolf and Burr, 2001).

Another treatment not currently advocated is the use of colour therapy. The use of the colour blue seemed to be of particular interest. Edwin Babbit (1878) in The Principles of Light and Color described its use for sunstroke (and other conditions such as sciatica, meningitis, and nervous headache) via a funnel-shaped device that used colour filters to focus light on specific body parts. Similarly, Colville (1914) also wrote about using light and colour in the treatment of sunstroke, stating that an individual's sunstroke ‘was quickly relieved by simply wearing a blue band or lining inside his customary hat’.

Conclusions

Heat illness has been known and written about for thousands of years. Over the years, there has been some improvement and refinement in the diagnosis and mechanisms, albeit with much debate and ideas that might appear to be at odds with our current understanding.

The use of water as a treatment, similarly, was originally described thousands of years ago, and perhaps the only treatment that has retained favour and continues to be used to this day. Many other treatments, for various reasons explored in this article, have fallen out of fashion.

Key Points

- Heat illness has been known and written about for thousands of years

- Despite this, the incidence of heat illness may still be increasing

- The beneficial effects of cooling the patient with water have also been known, though sometimes debated, for thousands of years

- Other historical treatments have been used but have gone in and out of fashion over the years

CPD Reflection Questions

- When was the effect of excess heat first written about?

- How has heat illness been treated in the past?

- What treatments are still in use and which have fallen out of favour?