In the United States (US), suicide claimed 47 646 lives in 2021 (Curtin et al, 2021); frequency increases with age and it is higher in the male sex (Rothberg et al, 2014). Suicide can manifest from a variety of mental disorders or unexpected life-altering events, with intervention considered an emergency.

Within the US healthcare system, acute crises of suicidal ideation and associated emergencies are often managed by the emergency department (ED), while primary care physicians typically manage patients who have previously made suicide attempts (Carrigan and Lynch, 2003). Appropriate treatment for these cases depends on a complete and coordinated evaluation of risk factors upon presentation.

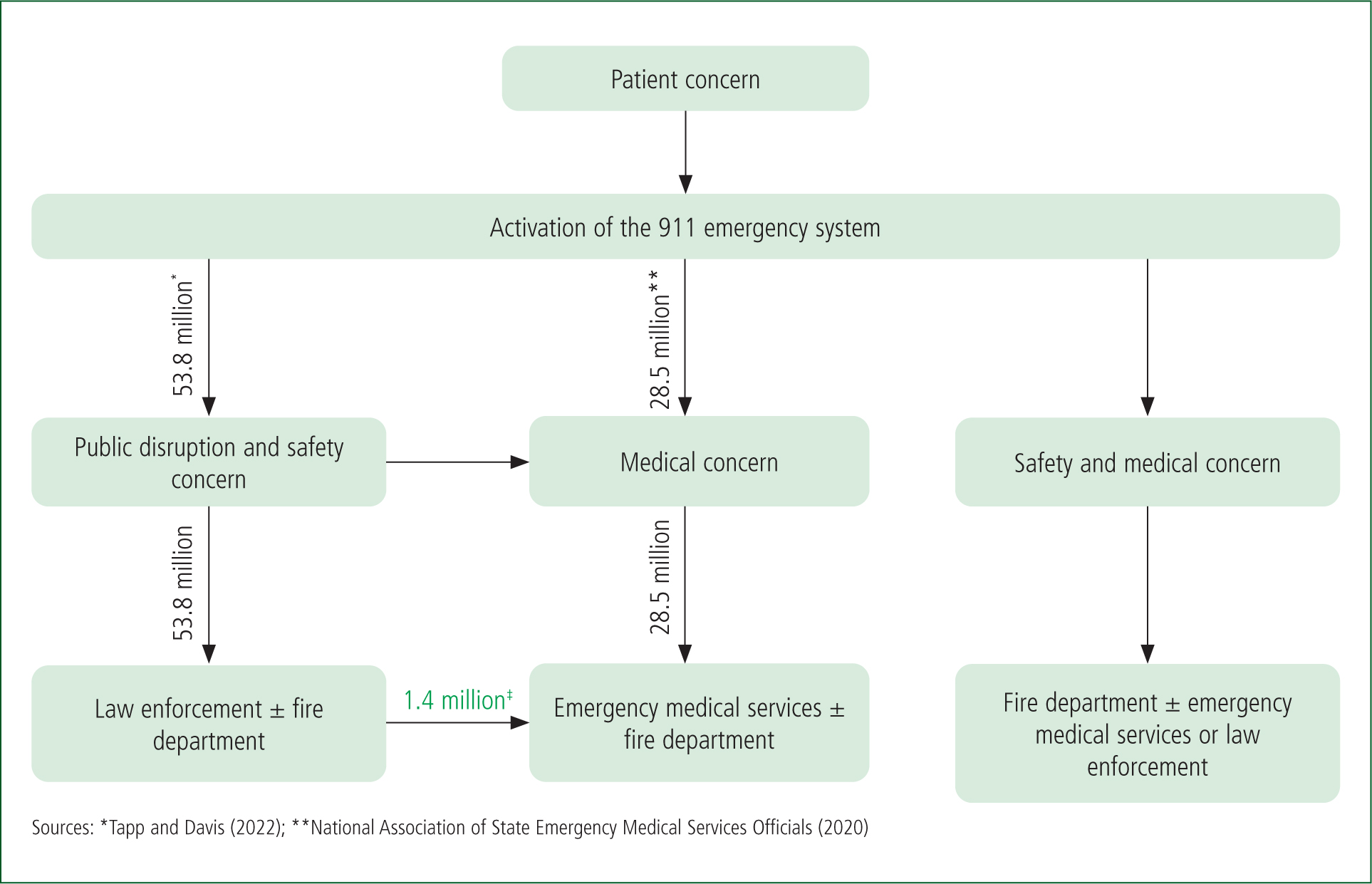

In the US, care provided to patients with suicidal ideation often begins with the 911 emergency system in the prehospital setting. While emergent access to the healthcare system is often provided by emergency medical services (EMS), EMS are not necessarily first on the scene. EMS are, however, essential for the coordination of care with other agencies, such as fire and police departments, as well as for safe transport of the patient to a definitive healthcare facility.

In the US, EMS rely on the 911 emergency system as the source of patient information but, owing to provisions outlined in the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), are prohibited from communicating with other first responder agencies freely. Additionally, patients with suicidal ideation with an immediate threat to harm themselves or others are often considered temporarily incapable of providing informed consent, such as that required to share their medical records between agencies (Farrow and O'Brien, 2003). These policies create gaps within the system which may result in unstratified, discontinuous care for urgent patients.

Prehospital care is particularly important for patients experiencing a suicidal ideation. In the case presented here, the patient attempted suicide by the infliction of penetrating head trauma, defined as trauma that breaches the skull and meninges surrounding the brain. These injuries are associated with worse outcomes than blunt force trauma to the head owing to their different traumatic pathophysiology (Kazim et al, 2011), including sequelae of abscesses, meningitis or encephalitis associated with breach of the blood-brain barrier (Bayston et al, 2000).

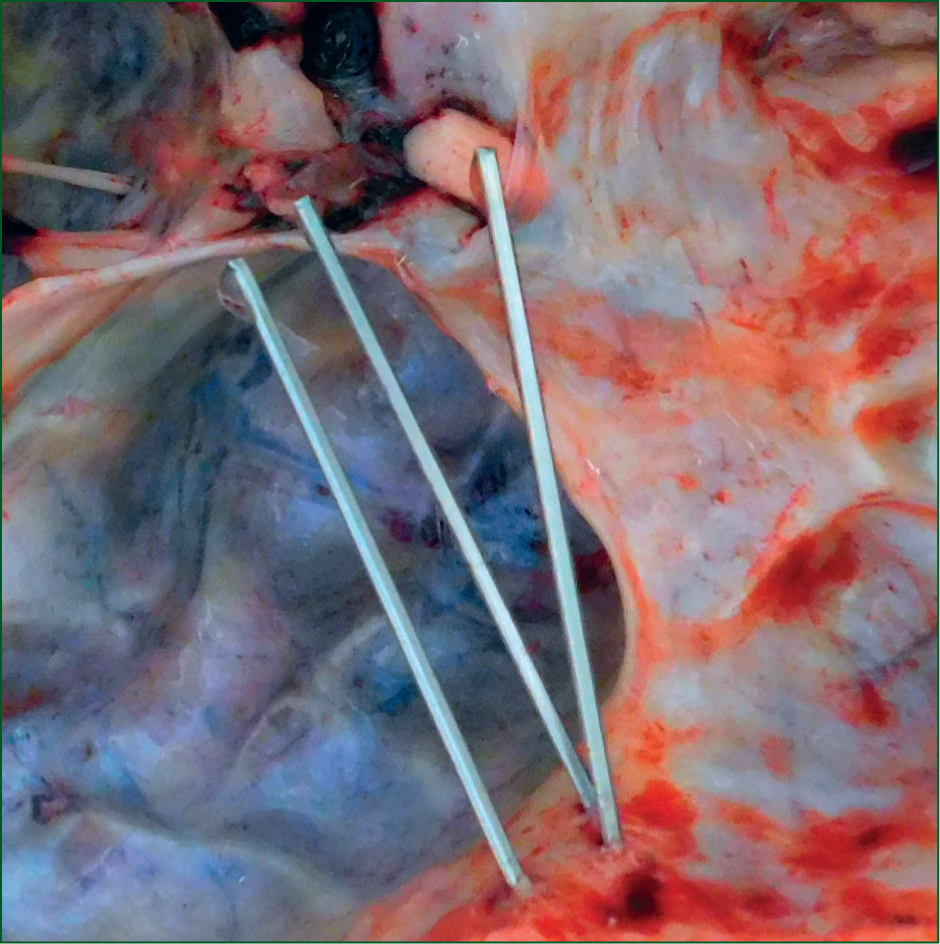

Penetrating injuries have two distinct types of damage: primary trauma caused by the object injuring the neural tissue; and a secondary brain injury associated with inflammation, haemorrhage, skull fracture and/or intracranial lesions from the embedded object. The primary injury presents as a focal ischaemic pattern of injury, while the secondary injury presents later in the clinical course and is characterised by neurotoxic biochemical cascades, haematoma formation and seizures (Andriessen et al, 2010; Kazim et al, 2011; Santiago et al, 2012; Alao et al, 2024).

The presentation of penetrating head trauma is highly variable depending on the location of the injury and can clinically appear very similar to a drug ingestion, an opiate overdose, stroke, myocardial infarction, alcohol intoxication and even diabetic ketoacidosis (Werner and Engelhard, 2007). Misidentification of penetrative head trauma may have dire effects on the health of the patient and may lead to permanent disability and even death (Santiago et al, 2012; Shahin and Robertson, 2012; Alao et al, 2024).

A case of a patient who attempted suicide using a pneumatic nail gun resulting in a delayed lethal injury to the head is presented to highlight the importance of training and cooperative inter-agency communication within emergency services in responding to cases of suicidal ideation.

Publication follows approval by the institutional review board and the organisational independent ethics committee, as well as gaining family consent.

Case report

A 911 call was received, which directed EMS to the home of an unresponsive 53-year-old man, reportedly with an altered mental status and a history of alcohol substance use disorder. Upon arrival, the patient had snoring respirations, was bradycardic (45 beats per minute (bpm)) and hypertensive (197/106 mmHg).

Naloxone hydrochloride was administered as there was suspicion of a drug overdose. During transport, the patient began vomiting, prompting intubation using etomidate and rocuronium.

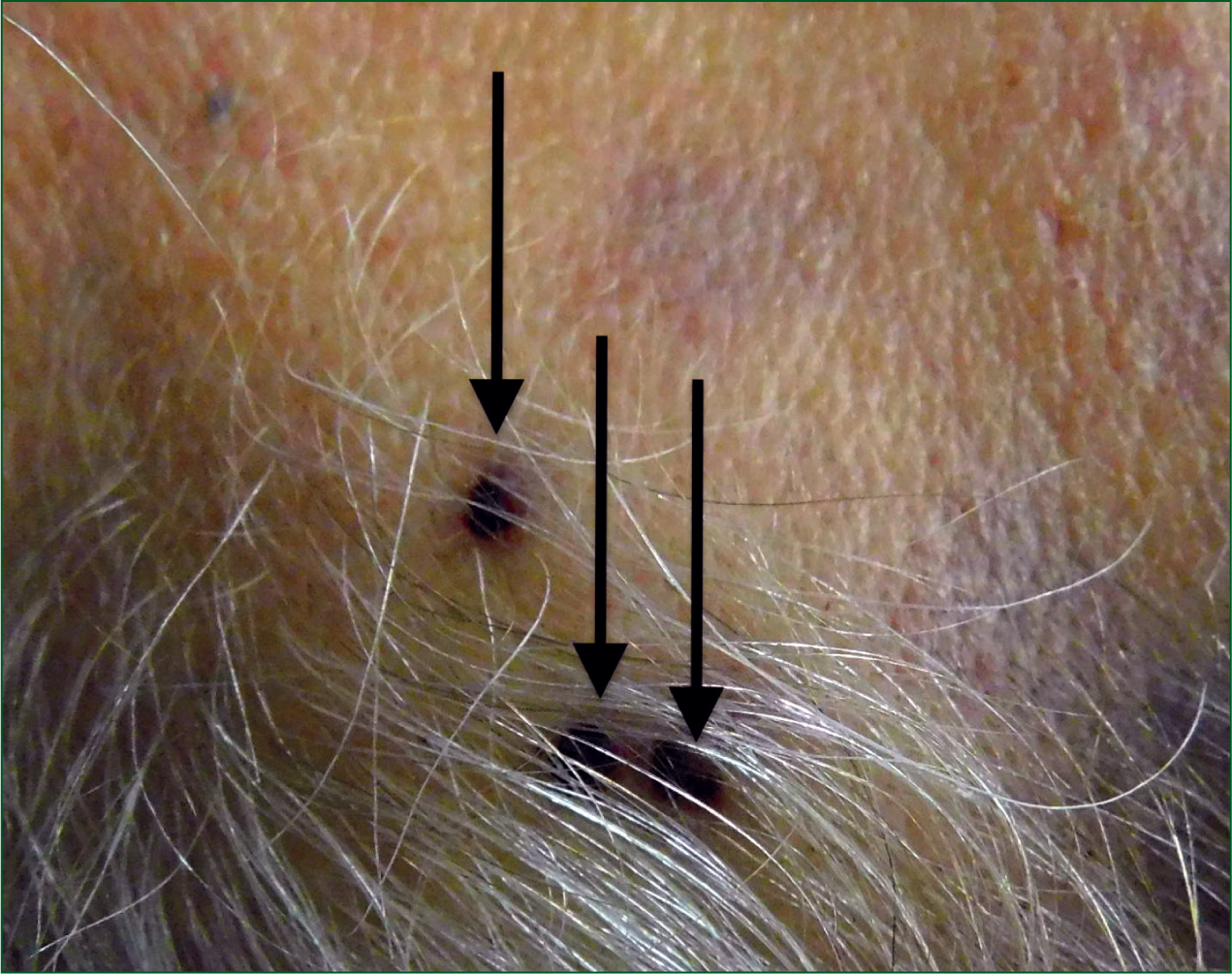

Upon arrival at the healthcare facility, EMS initiated the stroke protocol. In the ED, physical examination noted three metal objects under the patient's hair in the right temporal region along the hairline. No other physical abnormalities were noted. Hypothermia (90°F/32°C) was managed with warm intravenous (IV) fluids and a Bair Hugger.

Neural examination showed a Glasgow Coma Score (GCS) of 3T with fixed and non-reactive pupils, no pain withdrawal, posturing and no cough/gag reflex. A computed tomography (CT) scan was ordered; the patient was transferred to the surgical intensive care unit (ICU), and neurointensive care was consulted to rule out confounding factors such as sepsis, ingestion of foreign substances or other neurologic complications as part of a comprehensive neurological examination.

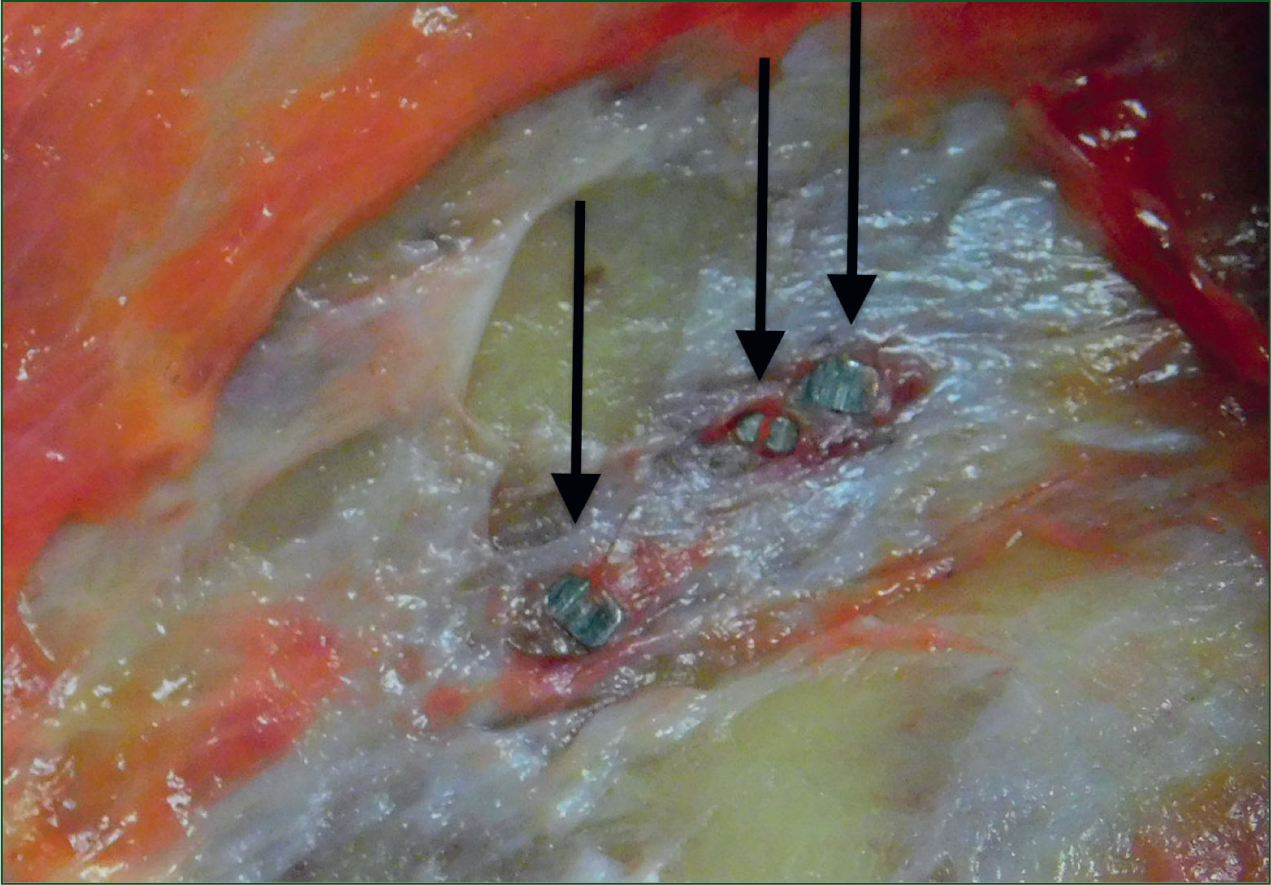

The CT revealed three metal objects (approximately two inches long each) extending from the temporal bone inward with intraparenchymal haemorrhage, sulcal effacement, intraventricular extension, 22 mm right-to-left shift, and subfalcine/uncal herniation with the basilar cisterns effaced. Mannitol (100 g IV in 3% saline), nicardipine and empiric cefepime were started. Hyperventilation (bed raised to 30°) was initiated.

To evaluate for a pulmonary embolus, a pulmonary CT angiography was completed; diffuse emphysema with infection appearing as nodular opacities in bilateral upper lobes were noted. Plugging/opacification to the left lower lobe bronchus, as well as the right lower lobe, was also identified.

Differential diagnoses included hypoxaemic respiratory failure, altered mental status of unspecified type, right-sided intracerebral haemorrhage, traumatic injury of the head, hypothermia and aspiration pneumonia of the left lower lobe.

At the request of the surgical care team, sugammadex was administered to reverse the neuromuscular blockade of rocuronium to perform a comprehensive neurological examination. Coughing was initiated with stable vital signs but an abnormal extension of his upper extremities.

Six hours after ICU admission, the patient became tachycardic (160–170 bpm) and hypotensive (85/43 mmHg). Stabilisation for blood pressure was initiated with vasopressin (20 U), epinephrine (2.5 mg) and norepinephrine (8 mg); IV adenosine (6 mg and 12 mg) IV and amiodarone (1 mg/minute) were unable to stabilise the tachycardia. These medical interventions wwere necessary as brain status had yet to be determined and the next of kin was required to consent for withdrawal of care and/or organ donation.

Once it was determined that the patient had a non-survivable head injury owing to extensive brain haemorrhage and increased intracranial pressure, and after consultation with the care team and family, comfort care was initiated. Extubation started 36 hours after EMS pickup.

Autopsy findings were significant for three finishing nails, two inches in length, penetrating partially through the right temporal bone with the nail heads flush with the outer table of the skull. (Figures 1–3) The patient's injury was associated with extensive intraparenchymal and intraventricular haemorrhage, with duret haemorrhages within the pons.

The patient's ethanol blood concentration was 0.13%. The manner of death was identified as suicide, with the cause of death being ‘penetration foreign body injuries of the head’. No other significant abnormalities were noted in the medical examiner's report.

Not stated in his medical record was the decedent's history of suicidal ideation. The coroner's report noted a call to law enforcement the day before the incident reporting that the patient was intoxicated and threatening to shoot himself with his pneumatic nail gun. The responding officers removed the nail gun from the patient and gave it to his significant other, who ‘hid’ it in the patient's office. EMS was never contacted during this initial encounter and this information was not communicated to the EMS during the following incident.

Discussion

Nail gun injuries tripled from 1991–2005, with 37 000 injuries reported between 2001–2005 alone (Woodall and Alleyne, 2012). When nail gun injury was specifically to the cranium, the injury was associated with a suicide attempt in more than 65% of reported cases (Woodall and Alleyne, 2012). The majority of patients with injuries present with no focal neurological changes, 40% have some sort of neurological deficit (evident through, for example, pronator drift, aphasia or signs of cranial nerve palsies) and 10% are comatose. Death from nail gun injury occurred only in patients who presented comatose, but only in 7.5% of the total number of patients presenting with cranial nail gun injuries.

While the case presented here resulted in mortality, reports indicate there can be full neurological recovery dependent on other factors, such as the time elapsed before medical care is started (Viswanathan et al, 1994; Beaver and Cheatham, 1999; Jithoo et al, 2001; Shakir et al, 2003; Rofail et al, 2005; Panourias et al, 2006; Adamo et al, 2010; Lee and Park, 2010; Aghabiklooei et al, 2012; Pomara et al, 2012; Oh et al, 2014; Agu and Orjiaku, 2016; Alain et al, 2018; Miner and Smith, 2018; Fernando and Ekanayake, 2021; Wang et al, 2021; Zhu et al, 2021).

A report similar to the case presented here examined a suicide attempt by the firing of a single nail into the left temple that was addressed immediately; GCS in the ED was 15 with no noted neurological deficits, and CT imaging demonstrated scattered left hemispheric and intraventricular subarachnoid haemorrhage. The wound was cleaned surgically, the nail removed and prophylactic antibiotics initiated, resulting in a full recovery (Zhu et al, 2021).

From their review of the literature and a similar case presented, the authors believe that the outcome may have been different had care been administered earlier. However, the elapsed time between the injury and EMS intervention was uncertain, and the nails were not immediately noticed because of their location within the individual's hair and the small nail head diameter of the finishing nails. Given that only a fraction of suicidal attempts using nail guns are successful, this case report demonstrates the value of understanding the pathophysiology of penetrating head trauma from nails and the importance of prehospital care for better patient outcomes.

This case additionally illustrates the importance of identifying improvement opportunities for inter-agency communication between first responder departments to increase response time and patient care. Ideally, the mental health status of a patient with multiple high-risk factors – such as a communicated suicidal ideation and the means to execute the plan, along with being of the male sex (Wortzel et al, 2014) and having a documented substance/alcohol use disorder – should have classified as high acute suicidal risk defined as ‘suicidal ideation with intent to die by suicide and inability to maintain safety without external support’. Hospitalisation should have been mandated for direct observation of the patient until care was delivered and modifiable risk factors were addressed (Betz and Boudreaux, 2016).

As has been noted by numerous studies, both in the US and internationally (Ding et al, 2023), inter-agency collaboration continues to be a struggle. In this case, clear communication regarding the psychiatric nature of the crisis (Strote and Harper, 2019) was imperative so earlier interventions or at least immediate medical attention regarding the nail gun wound would have been administered.

Education and training regarding the recognition of these risk factors and stratification for law enforcement officials could promote earlier EMS involvement and initiate entry of at-risk individuals into the healthcare system, potentially mitigating the likelihood of suicide.

Additionally, as law enforcement officers are typically first on the scene to de-escalate psychiatric emergencies and ensure the safety of citizens, training in de-escalation methods could not only promote safety for the patient, but also provide time for EMS support to arrive (Todak and James, 2018; Celofiga et al, 2022). It is only through EMS involvement that the chain of medical support for a patient can be initiated and they can receive the care they need.

In the US, EMS and fire departments rely on each other for stratified care and assistance in patient management (Høyer and Christensen, 2009). The communication system protects patient information and relies only on chief complaints and information concerning patient characteristics, in compliance with HIPAA protections. However, given the current case numbers (Figure 4), the communication strategy between law enforcement and EMS would benefit from a standardised and structured communication protocol for back-up assistance. This would be of benefit not only to patients with psychiatric emergencies, but also in all medical emergencies where EMS are not first on the scene (Wang et al, 2021).

Inclusion of law enforcement officials in the communication scheme provides a more comprehensive platform to optimise emergent patient care, particularly for emergencies involving suicidal ideation. These situations could be addressed using platforms such as the Multi Agency Incident Transfer (MAIT) system used in the UK, which allows emergency services to share incident records by location between local authorities on a single platform, thus promoting an appropriate response and reducing response times (HM Government, 2022). Additionally, as systems such as MAIT rely on the location only instead of patient identifiers, this strategy eliminates the concern of individuals being criminalised by their health information being shared with law enforcement.

Efforts to increase mental illness education within law enforcement have resulted in the development of crisis intervention teams (CITs). CITs aim to mitigate the stigma of mental health, improve communication skills and offer better insight to managing patients struggling with mental illness, especially through officer education (Nick et al, 2022).

Perceptions of the benefits of CITs have been very positive and they have given officers more confidence and preparedness to handle calls involving patients experiencing mental illness. CIT-trained officers are also able to direct patients to beneficial community resources that the patients would likely have not otherwise used without intervention (Bonfine et al, 2014). However, a recent systemic review focusing on the effectiveness of crisis interventions had inconclusive results, suggesting further investigation is needed on their role in managing patients with mental health crisis (Peterson and Densley, 2018).

Additionally, perhaps the integration of police officers within EMS to gain first-hand experience with medical professionals regarding these emergencies while also facilitating inter-agency collaboration may be helpful.

Conclusion

This case provides a new lens through which existing prehospital support system can be examined and allows the identification of areas in which growth and development can occur to improve the overall care available to patients experiencing suicidal ideation.

Engagement in mental health training for all individuals in the prehospital setting and developing communication networks that allow an efficient and effective exchange of information will expand healthcare reach and assist more patients in need.

Key Points

- Mental health crises are difficult to identify, which may result in care being delayed

- The statistical liklihood of suicide is higher in males and increases with age

- In the US, initial interactions with patients having suicidal ideation oftentimes occurs with the 911 emergency management system

- Penetrating head trauma can present similarly to drug ingestion, opiate overdose, stroke, myocardial infarction, alcohol intoxication or diabetic ketoacidosis, depending on the location of the trauma

- The majority of nail gun injuries to the cranium are suicide attempts

- While inter-agency communication between first responder departments remains disjointed, inclusion of law enforcement in this communication structure could aid patients in obtaining more emergent care, especially as it pertains to suicidal ideation

CPD Reflection Questions

- How would this case change your practice pattern if you encountered a patient with a similar presentation?

- How could communication between first responder agencies be improved for the betterment of patient care?

- How could programmes like crisis intervention teams improve patient care?