I referred a patient to an end-of-life care pathway for the first time as a newly qualified paramedic. The call was passed through on the mobile data terminal as an elderly patient experiencing shortness of breath – a run-of-the-mill call in the ambulance service.

The patient was non-verbal as a result of cognitive impairment, which can prove challenging for newly qualified paramedics (NQPs), including myself, who are fresh out of university, where OSCE patients would communicate verbally. Nonetheless, I spoke to my patient, but placed emphasis on my non-verbal communication. For example, before applying a blood pressure cuff, I held the area of the arm where I would place it to avoid startling them. I also held the patient's hand while the cuff inflated to relax them and build a rapport.

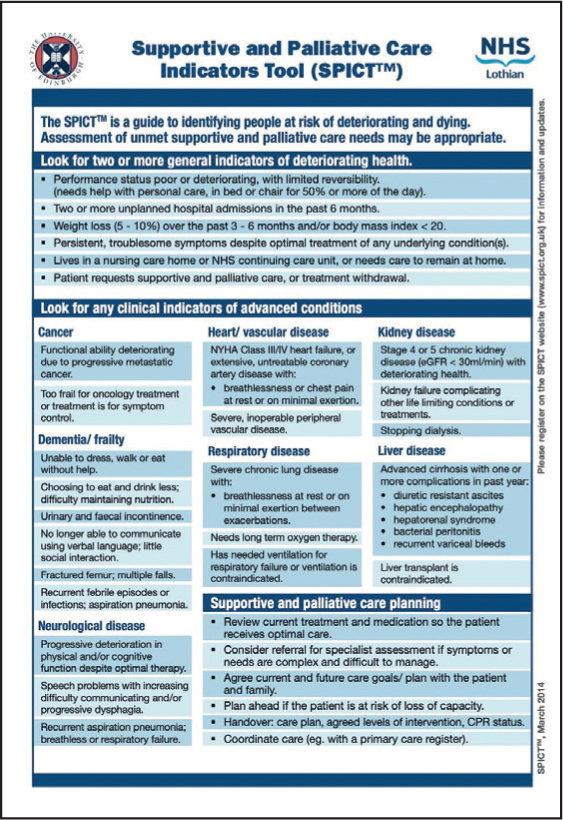

As an NQP, I partially rely on the patient's ideas, concerns and expectations, or ICE pneumonic to guide decision-making as it promotes holistic and patient-centred care. The family knew their relative was approaching end of life and strongly believed that accident and emergency (A+E) would cause stress. I reinforced this decision by using the SPICT tool (University of Edinburgh, 2021) (Figure 1), which helps identify people with deteriorating health due to life-shortening, serious health conditions to offer timely palliative care and future care planning, and I contacted their GP.

I found working as part of a multidisciplinary team (MDT) in the case of palliative care to be daunting as I felt under-experienced. However, as an ambulance service, we are often the first point of contact for a patient, to then refer to the MDT, which will promote the patient's physical, social and psychological health, in addition to supporting their families at such a delicate time. I spoke with the out-of-hours GP, which proved challenging as I had to explain the patient's history and today's situation while keeping the patient and their family's wishes at the heart of the conversation. This was aided by an open discussion between myself, the GP and the family, which resulted in the prescription of anticipatory medications for the patient.

‘Dying with dignity’ is a topic I am passionate about, and I believe this stems from university, as we were taught not only clinical care, but also holistic care. Holistic care can be challenging for NQPs, as we are often encouraged to ‘fix’ a problem that is in front of us, which can result in us becoming task-focused. It might have been easier to bring the patient to A+E and avoid the conversation with the GP, but this contradicts the ethical principles we are taught to practise.