Community public access defibrillation (cPAD) has only become a reality for local communities in the past couple of years as technology and guidelines from governing agencies such as the UK Resuscitation Council (UK) have been amended (Resuscitation Council, 2009). Due to the latest compliant defibrillation equipment, the need for training has been reduced and although desirable, is no longer necessary, even for members of the public.

cPAD schemes place an automatic or semi automatic defibrillator, a device used to treat sudden cardiac arrest, in a convenient location in a vandal and weather resistant box. The equipment can be accessed by anyone to assist a patient with a sudden cardiac arrest. In all cases, 999 is called and the ambulance service will give directions to the AED box to enable the defibrillator to be used. cPAD schemes are not a replacement for ambulance or community responder services but are there to help while professional help arrives, and have already been proven to save lives.

Why have cPAD schemes?

In 2009, the UK Resuscitation Council gave clear guidance on where a defibrillator should be positioned. Current international resuscitation guidelines (Rescuscitation Council, 2009) advise that evidence supports the establishment of public access defibrillation programmes when:

In real terms, this means most rural locations in the UK, and some city centre locations, with or without existing community first responder (CFR) cover. Over the past 10 years, many ambulance services in the UK have established CFR schemes, which are now considered essential local services for supporting some types of 999 incidents.

Statistically, based on data from the UK ambulance service, CFR schemes attend around 1 in 10 sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) events, mainly due to there being insufficient CFR volunteers to provide full geographical and full day/night cover.

cPAD are accessible 24 hours, 7 days a week, 365 days a year, and so are generally more readily available and can result in higher survival rates. The survival rate for cPAD schemes, based upon the latest clinical evidence in the UK, is approximately 26% (to leave hospital) compared to locations without the benefit of a cPAD at less than 3% (Colquhoun et al, 2008). Figures from the US, notably Seattle, where bystander CPR schemes are well established, only have a survival rate of 7.6% without defibrillation (Science Daily, 2009).

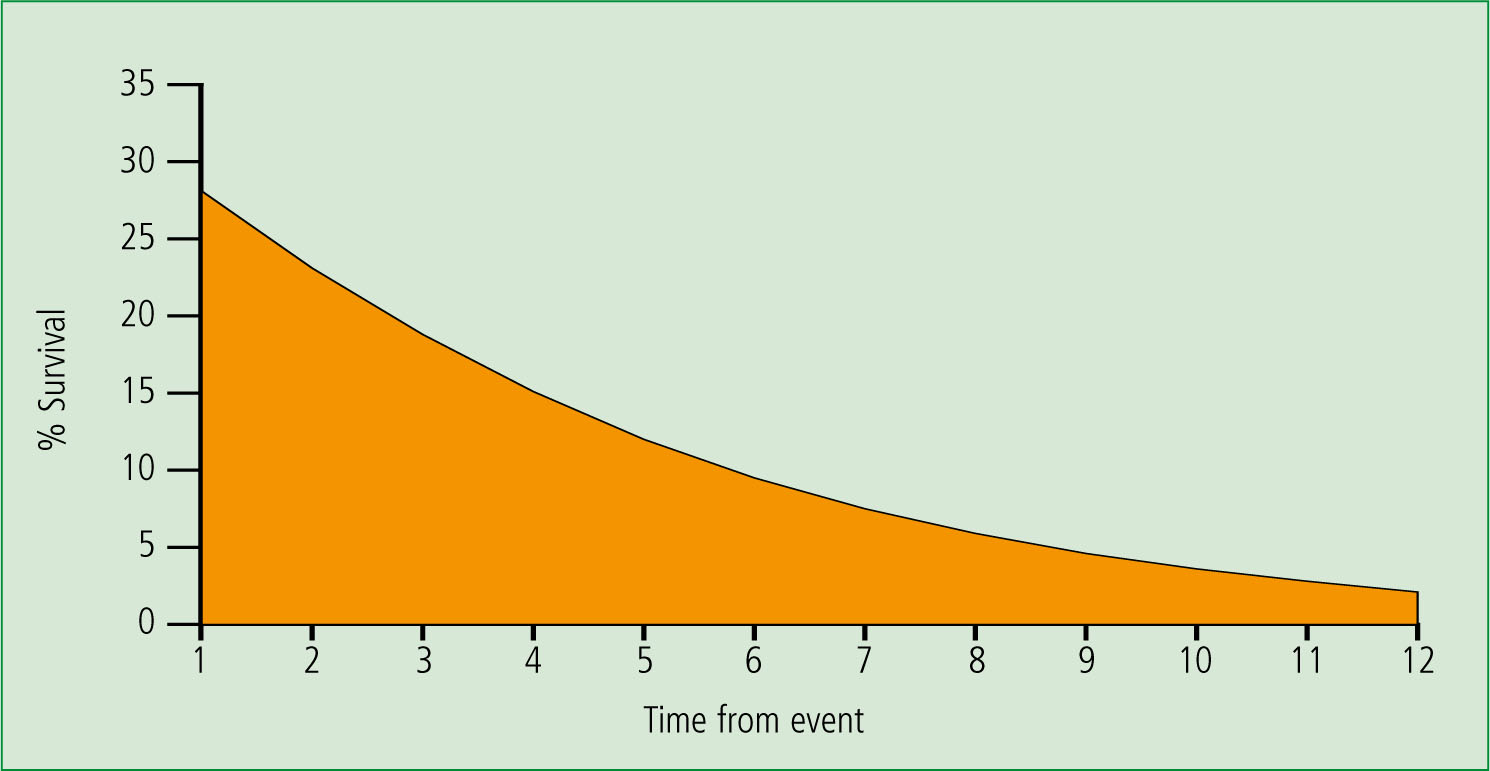

cPAD schemes are not in any way competitive to community first responder schemes, but are a natural adjunct to them, particularly where the cover by the CFR scheme is patchy and the numbers of calls do not justify the cost of a CFR scheme, or calls are intermittent or more than 5 minutes travel to the patient. Recovery from a sudden cardiac arrest is totally time dependent, the outcome degrading by 14–23% per minute post event (Figure 1) (De Maio VJ et al, 2003). Hence it should not be an either/or, but an integrated approach to better patient outcomes.

cPAD schemes are being installed for local villages by local community first responder groups, or other local village organizations; such as local charities (e.g. Lions, Rotary, Masons) or parish councils. Recently a CFR scheme that was one of the first to be established in the UK about 10 years ago, installed a Community Heartbeat Trust (CHT) cPAD scheme in its home village. ‘We installed the cPAD (at a country pub) as we were a mile away from the core of the village and there is no CFR volunteer nearby’ said Anne Chapman, one of the founders of the Essex based CFR group. ‘We are also intending to install one in the post office and also the other pub in the village.’

This responder scheme has 13 trained and active responders in a 9 square mile area and yet they cannot guarantee a response to all locations in less than 5 minutes. They concluded that a cPAD was a valuable adjunct to providing a local community resource for any possible cardiac arrests.

Yellow boxes

The CHT provides support for local communities to place defibrillators in vandal resistant heated secure boxes, coloured yellow for ease of visibility and rapid recognition. The colour has been chosen after testing with members of the public and in conjunction with the ambulance service (despite claims by other manufacturers there are, as yet, no central or international standards for AED box colour and various colour cabinets exist).

The AED cabinets can be lockable or not, there are good arguments either way, although in rural locations lockable is favoured both by ambulance services and local communities for a variety of reasons.

Ambulance services

All ambulance services across the country support the provision of cPAD schemes. Many have active programmes underway with the CHT. There are already several thousand defibrillators in large shopping centres and high footfall areas such as train stations and sports centres as a result of the national defibrillator campaign which ran several years ago.

Over the past few years, local communities have purchased defibrillators to try to provide their own schemes in village halls and local housing estates. Some of these have saved lives but, in general, have been un-coordinated and may be unknown to the local ambulance service, and in some instances have lacked ongoing equipment support.

‘If we could only get every GP surgery, every dental practice and most retail pharmacies placing defibs outside their premises, this would add an estimated 40 000 defibs into the public access at very little cost,’ says Martin Fagan, secretary of CHT.

With the central co-ordination and direction of such charities as the CHT, standardization of approach; training and equipment support; and increased purchasing power, is available to the benefit of the local community. It also provides a central point of liaison with the ambulance services, PCTs and Department of Health, as well as other charities and organizations involved with health in the community.

Case histories

Do these schemes work? A very telling example is that of the success of a cPAD scheme that occurred in Norfolk late in 2009, a scheme established by Holt responders. This is outlined in Box 1. This is not a unique example. However given the potential for survival, and the need for a fast response, cPAD schemes can and will continue to save lives.Another case history is outlined in Box 2.

Professor Douglas Chamberlain has a similar view: ‘Sudden out-of-hospital cardiac arrest cannot be a problem for ambulances if one wants best results.’ Professor Chamberlain has been an advocate for community defibrillation, and in particular members of the public both having access to defibrillators more readily, and also in being trained in good CPR techniques.

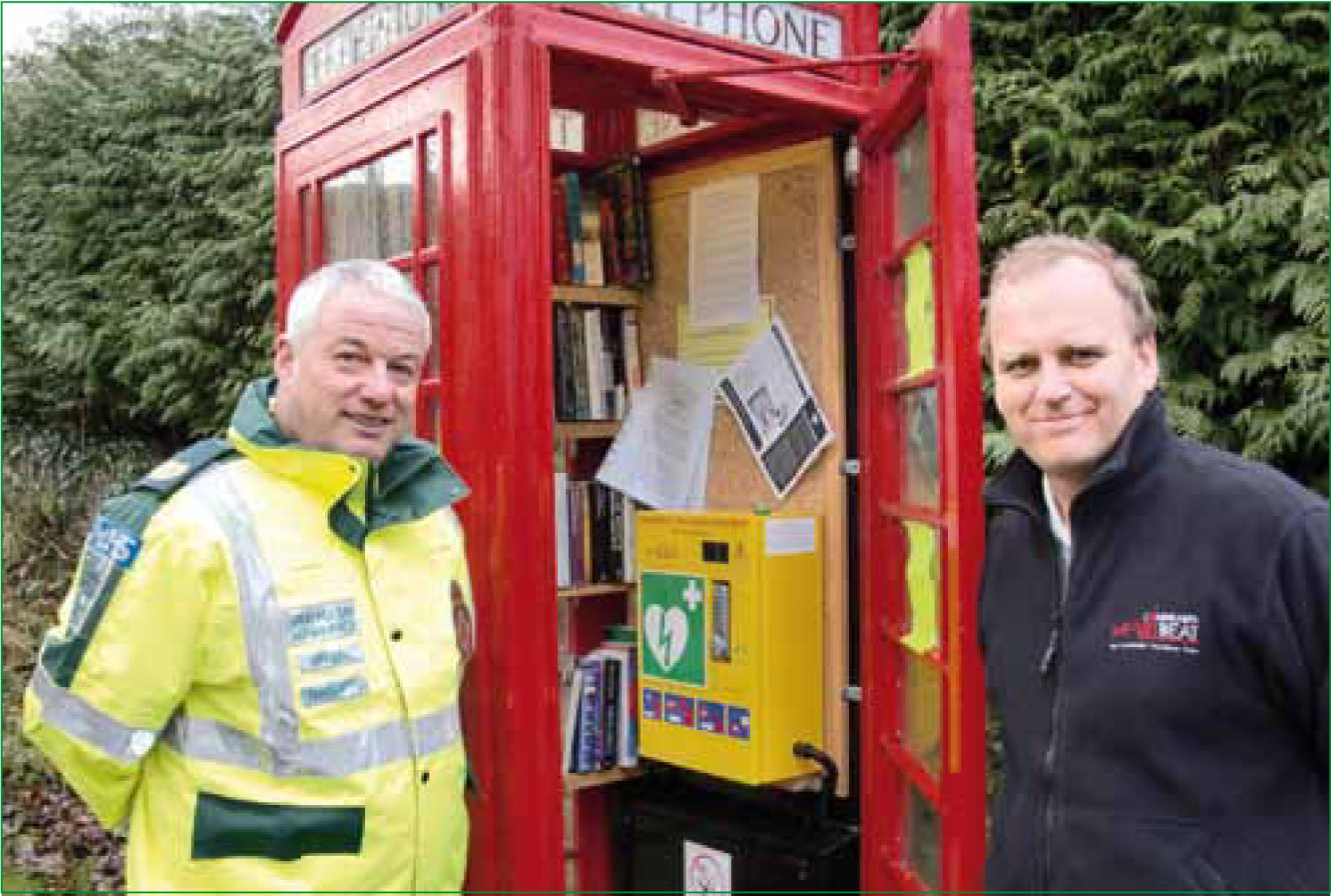

Telephone boxes

Defibrillators are also finding a place in telephone boxes. Working with British Telecom and the electricity providers, the CHT has now delivered several locations where redundant village telephone boxes have been used to house defibrillators. ‘The use of these iconic locations is ideal for defibrillators,’ says Mark Johnson, manager, BT Payphones. ‘They represent both an easily recognizable location, a use for a redundant but much loved icon, and also present a microclimate that helps support and protect the defibrillator.’

Another location with a telephone box AED solution is Chedworth in Gloucestershire, a project run with Great Western Ambulance. Commenting from Great Western Ambulance, Kevin Dickens said, ‘Developing this partnership with Community Heartbeat Trust is helping Great Western Ambulance Service extend our vision in creating a cardiac safe environment. This continues to build on our goal to make automated external defibrillators (AED) available to anyone at any time anywhere, achieving this will result in lives being saved.’

Conclusion

The excellent response to the work of CHT in 2010 makes the CHT one of the leading charities in rural community defibrillation, and its success is attributable to the excellent relationships with the ambulance services and local communities alike.

This has led to a reputation for delivery and innovation. CHT is not the only organization working in this area, but CHT serves to support local communities through and in conjunction with their local ambulance service, and in this way are seen as partners to the ambulance service.

Being ‘not for proft’ ensures almost all donations are used solely to fill the objects of the Charity. To date, CHT has projects working with 7 out of the 11 ambulance services in England, Wales Scotland and Northern Ireland.

cPADs should be as common as fire extinguishers and they are almost just as cheap. If a village or village organization is interested in a cPAD scheme, or just wishes to make a charitable donation, please contact the CHT via the website: www.communityheartbeat.org.uk, or e-mail: secretary@commuityheartbeat.org.uk, or via the local ambulance service.