Does everyone who calls 999 require a paramedic?

This provocative question is likely to divide opinions. Some may consider paramedic practice firmly in the prehospital emergency care domain, where recognition of deterioration and life-saving intervention is the core defining skill of a paramedic. This echoes frustrations that low-acuity and self-limiting illnesses, such as the common cold, fall into the domain of an urgent care practitioner or doctor. Conversely, others may perceive a paramedic as a first-contact clinician—one who can identify a range of conditions, irrespective of acuity, triage and manage appropriately. Additionally, one could argue that non-interventional emergency conditions such as a stroke might not require a paramedic, but rather an ambulance clinician who can recognise the signs and symptoms, and rapidly convey someone to the nearest appropriate facility. Irrespective of viewpoint, perhaps a more important question is: Is it fair for patients to expect a paramedic?

Indeed, paramedic attendance (as opposed to a non-registered ambulance clinician) reduces the likelihood of unnecessary conveyance (O'Cathain et al, 2018), which is partly due to a combination of knowledge and expertise, as well as greater empowerment to facilitate a discharge at the scene (Knowles et al, 2018; Blodgett et al, 2021). Yet, it is known that variation exists among paramedics themselves (O'Cathain et al, 2018). Black (2017) attributed variation as a combination of experience, exposure and education, as well as service demand and non-conveyance performance. In 2018, Lord Carter dissected the costs and efficiencies of ambulance services in England. This was an attempt to reduce variation and maximise productivity in service provision, such as the ‘job cycle’ (from patient contact to response to the outcome), and provide solutions to meet the increasing demand. Within the report, Lord Carter notes that the preferred model is to have a paramedic situated on every vehicle, subsequently acknowledging that with financial and workforce constraints, such a model is unattainable at present.

In essence, the ambulance service is a business—one that desires an affordable workforce, and quick job cycles to meet demand with good-quality care. It is easy to see the difficulty in achieving such goals at this time: current ambulance staff strikes suggest that the workforce is underpaid, and the long job cycle delays due to hospital handover and workforce shortages have placed patients at an increased risk of harm (Hussain, 2023). Such a picture of unfairness to patients and paramedics illustrates the importance of distributive justice.

This third article in the Ethics series which started last year (Robinson, 2022a; 2022b) departs from contractual justice and briefly explores aspects of paramedic distribution in the context of distributive justice, alongside how this can be used to improve paramedic practice at both the individual and service levels.

Distributive justice

The fair distribution of finite resources or ‘goods’ is distributive justice in its simplest form (Campbell, 2017). Rawls is perhaps the most influential contemporary figure who presented a generalised theory that argues for maximising the wellbeing of those worst off (Rawls, 1973). To justify this, he devised a thought experiment called the ‘veil of ignorance’, in which we assume no position within a society (rich or poor, healthy or sick) and have to determine how goods are distributed. The difficulty with this is that Rawls assumes people would rather not gamble on their health and wealth, instead favouring equality in those that are worst off.

An illustration

Ambulance service A is physician-led. Response time is fast, and diagnostic and treatment accuracy are high. The cost of a callout is £1000.

Ambulance service B is paramedic-led. Response time is average, and diagnostic and treatment accuracy are variable. The cost of a callout is £300.

Ambulance service C is paramedic-led. Response time is slow, but diagnostic and treatment accuracy are high. The cost of a callout is £200.

Ambulance service D is highly variable in clinician grade (doctor/paramedic/technician/care assistant-led). Response time is average, and diagnostic and treatment accuracy are highly variable. The cost of a callout is £100.

Imagine you are the patient; you may never need an ambulance, you might have a poorly managed disease requiring many calls, or you could have a significant emergency such as major trauma. Which ambulance service would you choose?

Whichever service is elected, the veil of ignorance elicits our own suppositions of what we might expect as a patient or, indeed, what we are willing to pay if the service is non-government funded. In a sense, it enables us to empathise with the patient. However, this perspective depends on what we determine as a ‘worst off’ patient. Is it the clinical presentation? For example, if someone is in a life-threatening condition, which type is more deserving than another—cardiac arrest versus major trauma, for instance? Could it be the patient's perception of the emergency that takes precedence, such as breathing difficulty over chest pain, even though these may be low-acuity presentations? Is it rapid access to a clinician or even the cost of an ambulance?

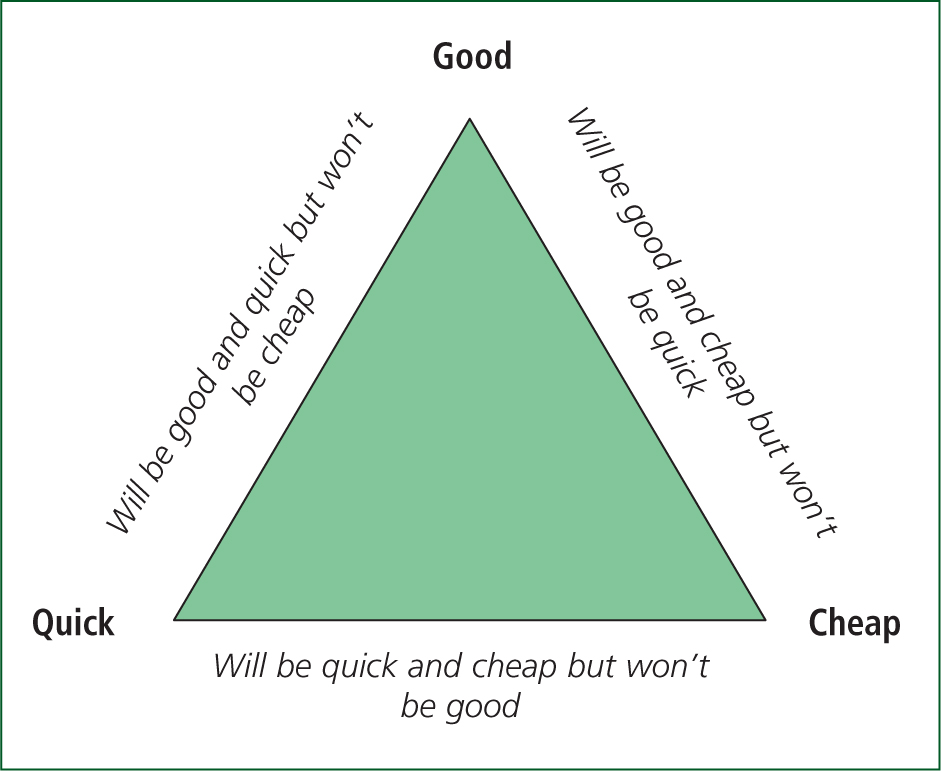

It is therefore difficult to interpret who is worst off, and how to effectively allocate a resource, which is a central criticism of Rawlsian theory. To resolve this dilemma, often distributive justice and healthcare concentrate on balancing the fundamental three factors in resource allocation: access, cost and quality, commonly known as the iron triangle (Carroll, 2012; van der Goes, 2019). The astute may have noticed that these themes are throughout this article.

The iron triangle

Resource allocation, also considered healthcare rationing, pertains to who receives a given treatment. Generally, only two of the three elements of the iron triangle can be met (Figure 1).

In the ambulance service, the focal point is about having quick access, leaving a conflict between good (for instance quality care from clinician grade or expertise) and cost. Hence, knowledgeable and experienced clinicians, as highlighted, clearly decrease costs elsewhere by reducing emergency department demand and any subsequent handover delays, but will not be cheap.

If in the earlier example, the ambulance services were one service whereby A–D were resources (A being critical care, B a paramedic-led dual-manned vehicle, C representing solo specialist urgent care paramedics, and D representing the relief workforce), it stands to reason that the more costly resources can be allocated effectively and appropriately. This helps demonstrate one method of how to optimise the iron triangle. Note that as with Rawls (1973), equal share does not in turn equate to a fair distribution. Some patients will benefit from a more specialist resource. Such resources ideally need to be proportionately available to the overall demand. If, for example, 1% of callouts require critical care, it would be fair to have sufficient specialist resources to cover this demand (broadly 1% of the workforce as a minimum).

Lord Carter's (2018) report predominantly focuses on this approach to reduce cost and increase productivity. For instance, he suggests decreasing solo-response vehicles. This limits the inappropriate allocation of multiple vehicles to the same incident, reduces the job cycle time by increasing patient access to ‘hear and treat’ for low-acuity presentations, as well as ambulance clinician access to senior support and pathways, to reduce unnecessary conveyance and a prolonged job cycle. Although a pertinent approach, arguably, these recommendations do not necessarily empower paramedics themselves: the possible inclusion of the core role to include phone consultation, and the potential reduction of autonomy by possible reliance on senior support, might deter those from retaining the role. In some ways, this links with Scanlon (1998); paramedics are not just a resource, they are members of society, and ought to have a greater opinion on the service they deliver, so long as these opinions are deemed reasonable by others. Hence, concepts such as ‘the veil of ignorance’ have utility in considering what empathically ought to be minimally available and expected by everyone, but serve as an initial step where research, evidence, and a diverse opinion of stakeholders (including paramedics) can shape theory into practice.

Conclusion

This article has only briefly introduced distributive justice in relation to the ambulance service. The initial questions, ‘Does everyone require a paramedic?’ and ‘Should they expect one?’, can be answered by considering what resources are available and how they ought to be distributed among society.

The ‘veil of ignorance’ is an empathic thought experiment that can place paramedics (and others) in the position of the patient who is worst off. Although ‘worst off’ is difficult to discern, it enables us to understand the level of care we would expect to receive. The dynamics of the iron triangle can then be used to illustrate how resources can be allocated fairly.

Therefore, not everyone requires or should expect a paramedic. Some require a more skilled clinician such as within the domains of critical or lower-acuity care. Likewise, health professional admissions without the need for intervention are unlikely to require a paramedic. Omitted from this article is the remarkable work of the rest of the ambulance workforce (technicians, nurses, care assistants) and the intention of this short dialogue is not to insinuate that their contribution is any less important than the work of paramedics.

How does distributive justice relate to paramedic practice at the individual level? The concept of the iron triangle should motivate paramedics to provide good-quality care with a desire for enhancing knowledge and expertise, for this will be evidenced through research and audit, and subsequently continue to increase the value of paramedics in the healthcare system. Importantly, expertise needs to be proportionate to the demands of paramedic practice. This includes the willingness of paramedics to explore and specialise in the increase of low-acuity presentations (as well as other frequent callouts such as mental health conditions and palliative care), as much as emergency care, which far exceeds the demands of critical care. Such an approach could increase productivity and empower autonomy—more so than recruiting a costly specialist that is a phone call away—which would deliver quality care much closer to the patient.

The final article in the series will delve into how justice impacts ambulance service treatment strategies, and how this affects both patients and the paramedic profession.