Some of you may be reading this article and frantically checking the calendar. Not for the day or the month but the year. Is it really 10 years since the Hazardous Area Response Team (HART) began? Well, dear reader, it is and yes it is 2016.

The HART programme has been operating for longer than you think. This article is intended to provide you with the history of the program from humble beginnings to the present day and maybe a hint of the future.

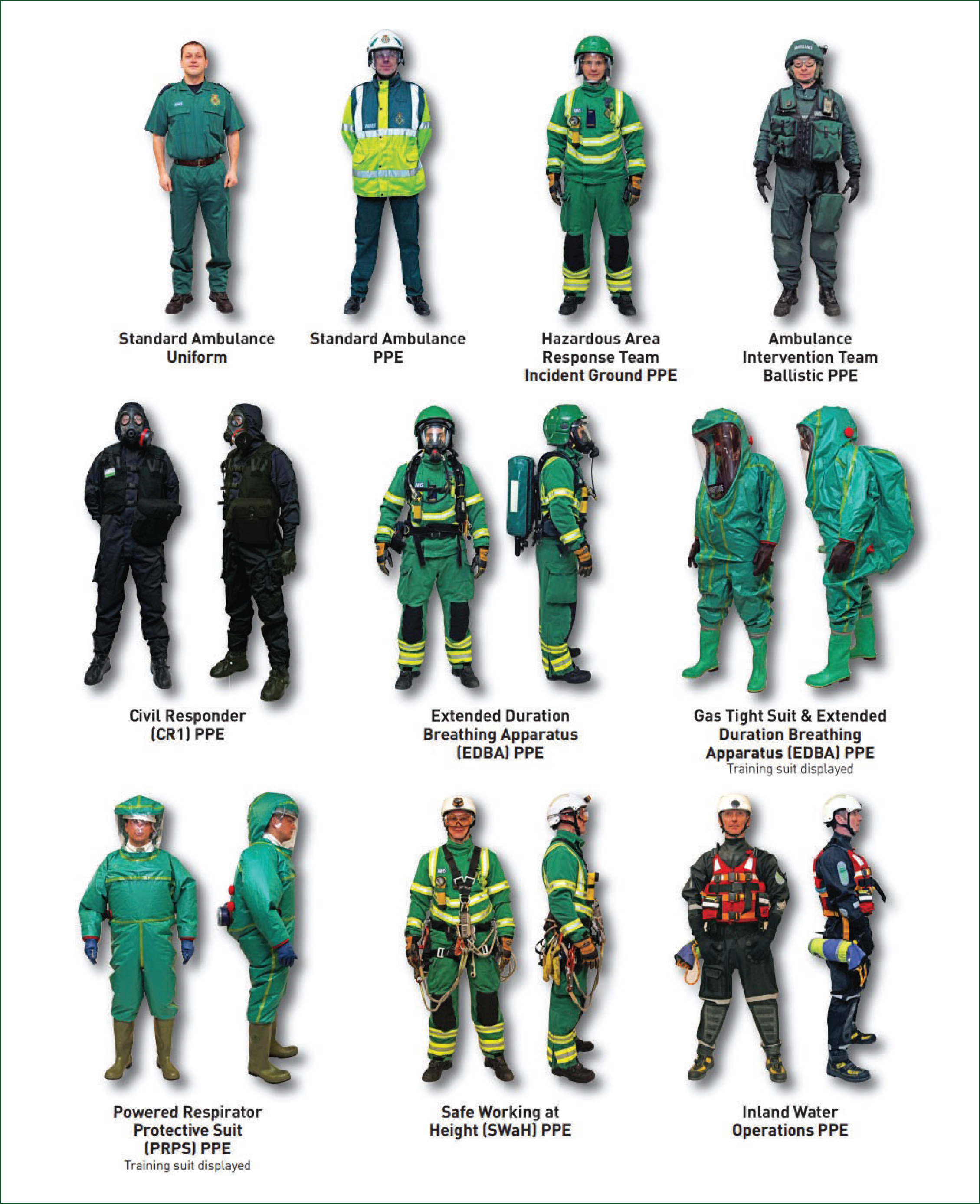

There has long been a strong interest from both the Department of Health and the ambulance service to see staff operating further forward in a major incident and delivering clinical care. Work had already begun with exercise Osiris 2 at Bank Street Underground Station in 2003. What research tells us is that outcomes are improved with early interventions with even the most basic of skills. The challenge is to deliver any level of care in a semi permissive environment whilst wearing PPE. PPE which, can greatly reduce dexterity and vision as well as the increased physical demands of breathing through respirator canisters, using a BA set and carrying heavy equipment.

The Hot Zone Working Project

The Hot Zone Working Project had been in operation since 2004 and was slowly but surely gathering its evidence on behalf of the Ambulance Service Association. At the same time, a Multi-Agency Initial Assessment Team (MAIAT) had begun a 12-month trial in London by London Ambulance Service NHS Trust (LAS), London Fire Brigade and the Metropolitan Police. There were two firsts for MAIAT which included a multi-agency base and vehicle set up, but it also saw paramedics trained in breathing apparatus and respirators so they could access patients in hazardous areas.

The evidence from the Hot Zone Working Project and MAIAT was submitted to the Department of Health in early 2005 with the expectation of a long deliberation. The tragic events of the 7 July 2005 accelerated discussions as MAIAT was deployed and a decision and funding were allocated shortly afterwards. The next 6 months proved to be busy, challenging and rewarding for all involved, who now had the opportunity to improve the health response to these types of incidents and critically improve the outcomes for patients.

Identifying two key skill sets

There were two key skill sets that were identified early on. The first was the chemical, biological, radiological, nuclear (CBRN)/Hazmat element which was entitled Incident Response Unit (IRU). The second was the structural impact of terrorist incidents and so at the request of the Chief Fire Officers Association, the Urban Search and Rescue skill set was also considered key. A risk assessment determined the greatest threat of CBRN incidents to be London, so IRU was given to London Ambulance Service NHS Trust, and Yorkshire Ambulance Service NHS Trust (YAS) offered to trial USAR.

The decision to trial these particular capabilities proved pivotal when in early 2007 a collapsed structure in east London saw many patients trapped and requiring treatment. A call and indeed the first HART Mutual Aid request went to YAS who duly despatched a team to support LAS (BBC News, 2007).

Setting up Hazardous Area Response Teams

In 2008, other ambulance Trusts were being asked to begin setting up what now became known as a Hazardous Area Response Team. Trusts such as West Midlands Ambulance Service NHS Foundation Trust would begin with USAR and then were funded to recruit the balance of staff to form a team consisting of 42. This was divided into seven teams of six staff each with a team leader. What was crucial to the support from ambulance Trusts is that they were all paid the backfill costs to create HART. Therefore, each Trust ended up with its original core establishment plus the 42 HART staff and their management team.

As the trial concluded, the IRU and USAR capabilities were rolled into a single team. HART has 42 staff, with 24 of them who have undergone USAR training as well. However, during the roll out across the country, other threats began to emerge and HART were viewed as the team that could bridge that health gap.

Inland Water Operations

The first additional skill set was Inland Water Operations (IWO). The floods in the Summer of 2007 tested flood rescue capability across England. The Pitt Review concluded a national concept of operations was required for all emergency services and voluntary organisations (Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA), 2012). IWO began life as a HART-specific course that sat outside the DEFRA guidance as it was a half-way house between Level 2 and Level 3 water rescue training. It was soon recognised that to improve interoperability, and in particular with Fire Rescue Service colleagues, we needed to follow the DEFRA Concept of Operations and all staff in HART are now trained and operate at Level 3, water rescue technician and water rescue technician team leader. This also saw us adopt the national helmet colouring system as well.

Tactical Medical Operations

The threat of terrorists using high powered automatic weapons has been recognised as a significant threat to the UK for a number of years, and from a health perspective HART were called upon again to fulfil that gap. HART can also support the police in firearms-related incidents under a skill set known as Tactical Medical Operations (TMO). We are now supported by ambulance Trust staff who work with HART during incidents of Marauding Terrorist Firearms Attack (MTFA).

Training is key

The key component to HART that has been the central part of all we do is training. As you can see HART have four core capabilities: IRU, USAR, IWO and TMO. This requires a huge amount of initial training as well as having protected training for each team every 7 weeks. If the training and core competencies are not completed, then the risk of working in all these areas to the staff as well as the liability for each of the ambulance Trusts quickly becomes apparent.

So where did our training begin? What is important to remember is that a HART paramedic is no different to the paramedic you will see on an ambulance or rapid response vehicle from a clinical perspective. The only difference is the HART takes those skills into high-risk areas and to do so needs specialist personal protective equipment (PPE) and training. The core of what HART does always has been, as Peter Bradley might say, ‘taking healthcare to the patient,’ wherever they are (Bradley, 2005).

The first IRU course which covered CBRN and Hazardous Materials, among other topics, was held at St Martyn's Plain Camp in Folkestone in 2006. LAS have a strong relationship with London Fire Brigade (LFB), who provided LAS HART with their BA course. As other teams began to roll out across the country utilising the local FRS to provide a BA course for HART helped forge the strong interoperability links we see today.

The USAR course was developed in conjunction with the Chief Fire Officers Association, as well as the Fire Service College at Moreton in Marsh, where the course was subsequently delivered.

When the roll out was completed, the Department of Health handed ownership to local Trusts. However, as this now became a commissioned service by NHS England, the National Ambulance Resilience Unit (NARU), took the lead for policies and procedures, as well as coordinating and delivering the training. The training is led by Dave Bull QAM, who has been involved in the training since HART began. Today his team delivers training not just for HART but for all levels of ambulance command through the NARU Education Centre.

HART is not without its risks to the staff and ambulance Trusts who provide them, but this is mitigated with world-class training at NARU and, in recognising our unique role within the NHS, we have a dedicated compliance officer, Chris Cooper, who as an experienced HART manager can translate legal necessity into operational governance. This has been a hugely important area of work for the ambulance service as we have a different legal duty to our police and fire colleagues following Kent v Griffiths [2000], an English tort law case from the Court of Appeal. Upon acceptance of the 999 call we have a duty of care to that patient where ever they are and HART can now access those patients to provide lifesaving treatment.

The future for HART

So what does the future hold for HART? While 10 years may seem a long time in some respects, the first half saw the roll out and the second half adding capabilities and so some consolidation is required. However, our identity is well established both within the ambulance sector and with multi-agency partners. Skillset wise we have demonstrated that if risks change we can adapt and implement very quickly.

The next steps for HART are new vehicles and IT. NARU have conducted and awarded tenders for vehicles and IT over the past 12 months. It has been recognised that IT changes much more quickly than vehicles and so to leverage that the replacement period has been reduced to 4 years. The IT is also fully portable so we can visit the community cut off by flooding and set up a clinic and access their health records and support them in times of crisis, for example. We also maintain our ability to broadcast video, live, to anywhere in the world from an incident using body worn and static cameras, as well as our forthcoming drone capability. HART across the country will now begin to move to our new operational model of primary, secondary and resupply/welfare vehicles.

HART—improvise, adapt and overcome. Now where I have I heard that before?