The first part of the series on child public health introduced how an effective strategy can lead to a healthy life course from childhood onwards, and how paramedics can contribute to these strategies. Part 2 focuses on prevention in more detail, exploring with the use of examples the intricacy of employing preventative techniques to avert diseases from affecting the lives of children, and where paramedics implement such methods into practice.

Prevention refers to the strategy of hindering the onset of disease, improving health and wellbeing (Eyler and Brownson, 2016). According to Blair et al (2010), it occurs at the following three levels:

Primary prevention

At the primary level, child public health aims to stop disease or conditions from occurring in the first place (Blair et al, 2010). Examples include healthy eating to reduce the development of obesity and diabetes, and immunisation. The success of a primary prevention strategy is measured by the extent to which a specific disease is prevented (Blair et al, 2010). For instance, meningococcal septicaemia has significantly declined since the administration of a vaccine (World Health Organization, 2020), and is reported to no longer be the leading cause of death of children in the UK (Viner et al, 2018).

However, establishing an effective primary prevention strategy is a complex process, particularly in the case of immunisation. For instance, the BCG vaccination for tuberculosis (TB), routinely given to school children in the UK until 2005, is now only given to high-risk groups owing to the low risk of exposure to TB for the general population (Abbott et al, 2019). TB has been found to decline through improved quality housing, screening and better hygiene, rather than through vaccination itself (Bhargava et al, 2011; Thomas et al, 2018). Generations now present a scar on the upper arm that need not be there. Thus, careful consideration needs to be given to the cost/risk-benefit efficacy of the childhood immunisation strategy, and whether reasonable alternatives are equally or more effective.

Below are some further examples to reflect upon:

Paramedics in ambulance services and primary care settings are in a position to assess the immunisation and health status of every child they encounter. Accordingly, any discrepancy in a child's immunisation status or identification of any unmet healthcare need ought to be further discussed with the family, and referred to a general practitioner (GP) or paediatrician for review. To achieve this, paramedics ought to:

Secondary prevention

Arguably the area that paramedics reside in, secondary prevention denotes the early identification of disease so that it can be reversed or limited through early intervention (Blair et al, 2010). In the ambulance service, this approach extends to recognising a deteriorating child, early interventions such as adrenaline for anaphylaxis or benzylpenicillin for suspected meningococcal septicaemia, and initiating any necessary resuscitative measures (Association of Ambulance Chief Executives (AACE), 2019). For paramedics in primary care, this could also include the notion of screening for disorders, such as diabetes (Blair et al, 2010).

An issue of secondary prevention is that many approaches are screened to a threshold, with risks of declaring a child having a disease when they do not (a false-positive), or declaring a child does not, when they do (a false-negative) (Elliman, 2019). For instance, sepsis-screening tools or paediatric early warning scores (PEWS) are often implemented to detect the risk of a condition, or the possibility that a child may deteriorate. Detection of certain vital signs or observations achieve a threshold that instigates a treatment plan. A classic example is the sepsis bundle and escalation of care, such as oxygen and fluid therapy and rapid transport in the prehospital setting (AACE, 2019). However, not all children will have sepsis without further tests to confirm; a reason why in the prehospital setting, sepsis is not diagnosed and is labelled as ‘red-flag sepsis’ until proven otherwise.

Some tools, such as the UK Sepsis Trust Screening Action Tools (Nutbeam and Daniels, 2020), have been endorsed by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), and are implemented into paramedic practice (AACE, 2019), whereas PEWS have demonstrated poor discrimination of predicting hospital admission from the prehospital setting (Broughton and Maconochie, 2019; Corfield et al, 2020), and may result in inappropriate care plans that result in harm to the child. Therefore, screening must meet certain criteria before it is implemented into practice, including:

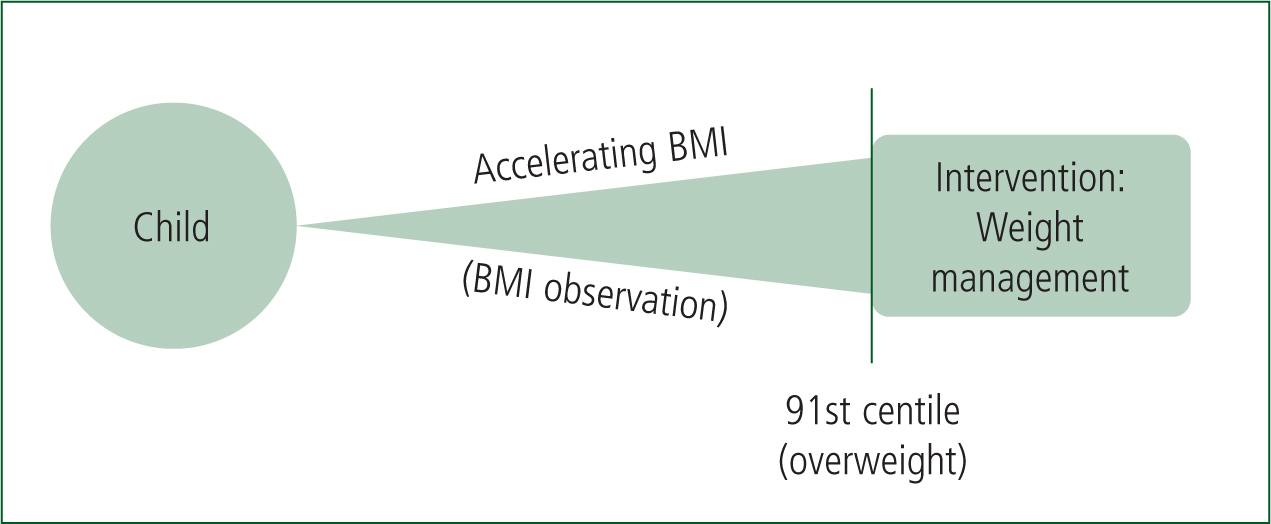

However, many health conditions sit on a continuum of severity, where a threshold line does not necessarily demarcate a child at risk of disease from one that is not (Blair et al, 2010). Body mass index (BMI), for example, an indication for obesity, cannot predict child obesity that continues into adulthood from a single value alone (Geserick et al, 2018). Likewise, labelling a child with a high BMI as obese may have psychological implications such as depression (Rankin et al, 2016). Yet, the burden of the child obesity epidemic continues to affect many children in the UK, with long-term implications of cardiovascular, mental health and cancer risks throughout the lifetime (Viner et al, 2018). Thus, NICE (2014) has advised a child reaching a threshold of BMI greater than the 91st centile (overweight) needs intervention. Arguably however, observing the trend of an accelerating BMI, particularly before the age of six, as highlighted by Geserick et al (2018), is a more effective approach for managing obesity (see Figure 1 for a visual example).

While paramedics predominantly remain within an ambulance setting, rendering it impractical to screen children over time due to the short-term relationship with the child and lack of equipment such as scales, the concept of screening is particularly important for paramedics to understand in primary care. Primary care paramedics may encounter a child (or any individual) on a more frequent basis, where screening assessments are recognised within the core capability framework for primary and urgent care paramedics to incorporate within their practice (College of Paramedics, 2019). Whether primary care paramedics are sufficiently trained in assessing child health and in relevant prevention strategies is an under-researched area, which warrants further investigation to help support the growing role of paramedics in primary care.

However, in the case of child obesity, reasonable practical steps for a primary care paramedic to undertake include:

Tertiary prevention

The third level of prevention involves hindering the progress of established disease or disability, and improving the life of the sufferer and their family (Blair et al, 2010). Chronic conditions such as diabetes, asthma, and epilepsy are diseases that ought to be managed by specialist teams within the community, such as the provision of an effective insulin plan for diabetes, or inhalers to reduce the frequency of a child's asthma attacks. Indeed, unnecessary hospital admissions for these conditions are on the decline (Royal College of Paediatric and Child Health (RCPCH), 2020).

While paramedics currently have no significant roles within specialist teams in tertiary prevention, they may be among the first health professionals to connect with a child disengaging from services, or requiring urgent review of their management plan. Examples include a child non-adherent to their insulin regimen, or where a young person with epilepsy begins drinking alcohol, reducing the effectiveness of their medication resulting in an increase in seizures. Accordingly, paramedics in ambulance services, who respond to children in an unscheduled manner (as opposed to scheduled appointments that specialist teams rely upon) are uniquely positioned to access a child in need, providing a critical opportunity to discuss and capture concerns of the child and family, offer advice, and relay to a specialist team that a child's management plan requires urgent review.

Conclusion

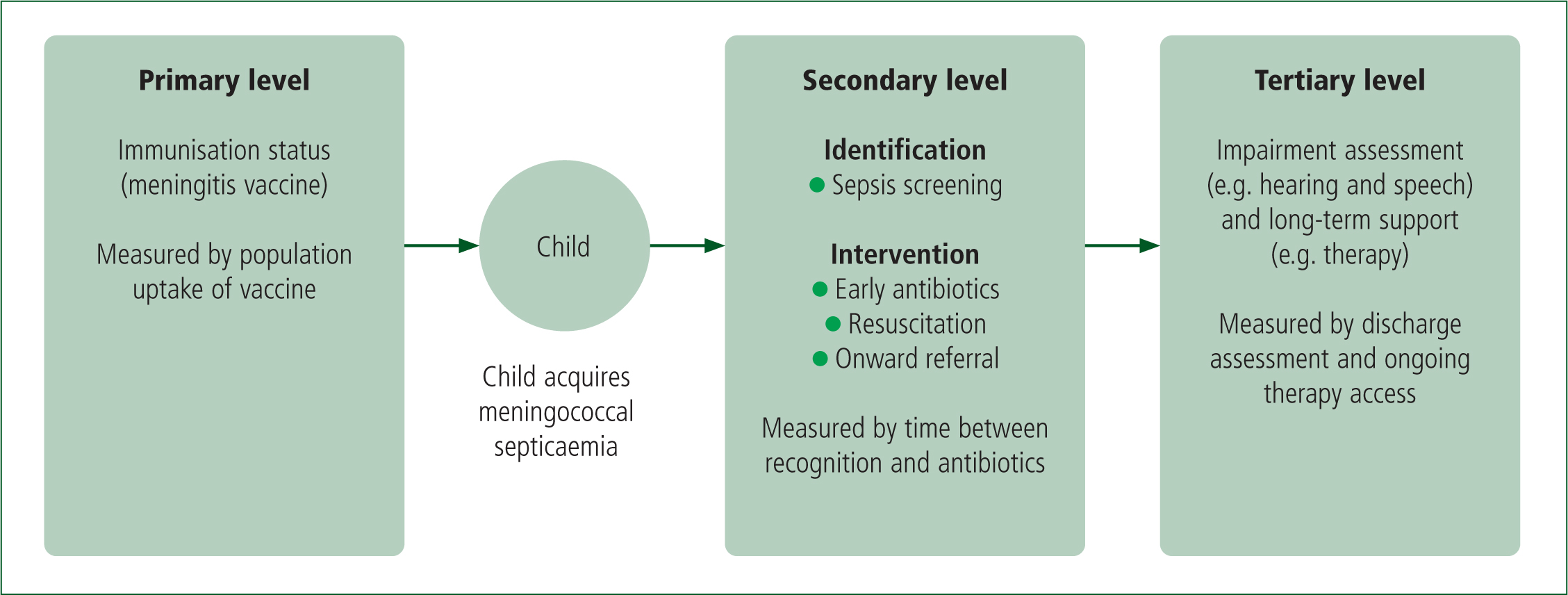

Paramedics are involved in all levels of prevention, where they can identify and assess a child's health status and initiate an intervention, typically by onwardly referring a child to a specialist team. It is therefore important that paramedics understand the child's journey through the levels, and where paramedics contribute. Figure 2 illustrates the different levels of prevention in action as a child experiences meningococcal septicaemia.

Although paramedics in ambulance services have only short-term contact with their patients, they are in a unique position to engage with children in a time of need, providing interventions that rapidly hinder the progress of a disease, as well as access hard-to-reach children, offering an opportunity to relay them to services that a child might otherwise be disengaged from. In contrast, primary care paramedics may have a higher degree of involvement with the continued care of a child, such as ongoing screening and regular health reviews.

Parts three and four of this series will focus on promoting child health strategies, and protecting children to safely develop within society.