The previous two articles in this short four-part series introduced the notion of child public health, and prevention strategies in improving the health status of children, mitigating the consequences of disease. The position of paramedics within the community places them in an ideal situation to connect with children and their families as one of the first intervening health professionals, and with those that are hard to reach and disengaged from other scheduled health services. This offers the chance for a paramedic to give health promotion advice to those likely to be reaching out, for example regarding smoking cessation, healthy eating, or advice on medication adherence such as the importance of regularly taking insulin.

Indeed, paramedics in both prehospital and primary care settings should be familiar with the Make Every Contact Count campaign (Public Health England (PHE), 2016), where any patient encounter provides an opportunity for clinicians to assess, signpost and encourage individuals to adopt healthy behaviours that reduce the risk of long-term diseases. The Make Every Contact Count campaign is an example of health promotion, that in effect, encourages and empowers individuals, communities and populations to adopt a positive, healthy lifestyle (Blair et al, 2010). Although this sounds like a simple concept, there can be conflict between the community and individual level, resulting in inequality and disempowerment. Examples specific to paramedics include:

The following article aims to broaden paramedic understanding of health promotion, uncover theories as to why and how disequilibrium occurs in promotional strategies, and where paramedics can contribute and limit such issues.

Strategies of health promotion

In 1986, the World Health Organization (WHO) met in Ottawa with the aim of promoting ‘Health for All’ by the year 2000 and beyond. Born out of that meeting was the Ottawa Charter, consisting of three core strategies for health promotion (WHO, 1986):

Implementing these three strategies can occur across three levels: the individual, including empowerment and health awareness; community, social action and communal empowerment; and policy, advocacy directed at public health (Blair et al, 2010). For child health in the UK, those primarily responsibility for health promotion are the government, clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) (including general practitioners (GPs) and other health professionals), and the education system (Blair, 2014).

A key concept is empowerment, considering the level of control or agency an individual or community has over determining the quality of their life (Tengland, 2012). The greater the level of empowerment, the more likely it is to influence a long-term positive change, and an increased sense of ownership and self-esteem (Blair et al, 2010). Not all methods of health promotion are empowering; however, some governments prohibit children from attending school if they are not sufficiently immunised, arguably penalising a child for a parental decision. In contrast, a more acceptable enforcement is the mandatory use of seatbelts and reduced speed limits in neighbourhood areas, which have greatly reduced childhood unintentional injury (Patel et al, 2017).

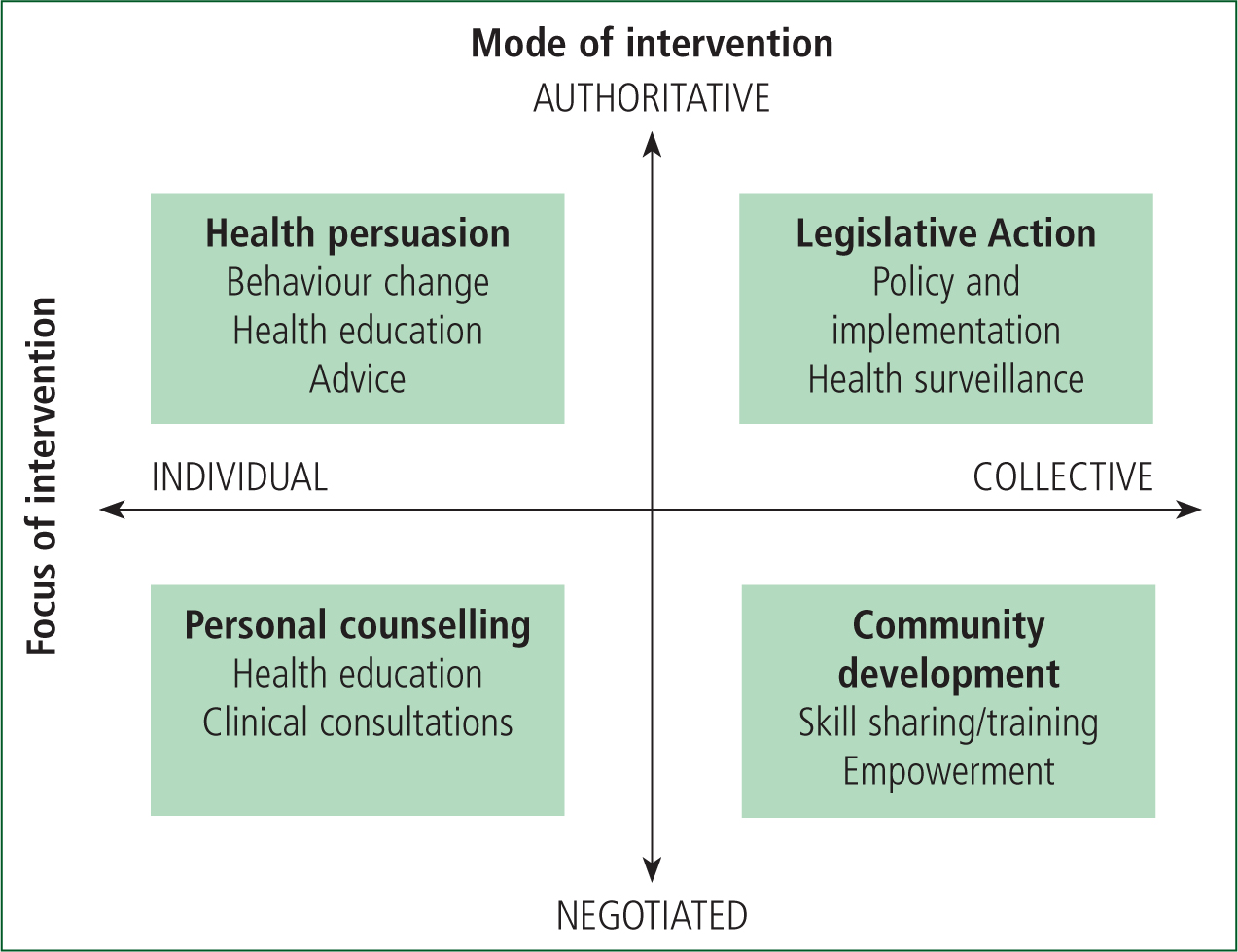

Beattie's (1991) model of health promotion (Figure 1) is a useful visual tool that helps dissect what type of approach a health promotion strategy adopts. For instance, the earlier example of a policy of ‘all children under 2 years old must be conveyed’ is a legislative action. Such implementation is disempowering for individual families and paramedics, and while the policy protects this vulnerable group from unforeseen consequences, the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health has advised that the policy be reviewed with improved decision tools and support networks (Walton et al, 2015). This latter action can be considered ‘community development’, and would encourage CCGs, families and paramedics to formulate an improved care pathway.

Paramedic encounters with patients, both in prehospital and primary care, are on the left side of the model, and may shift from a negotiated mode of intervention to an authoritative, persuasive one. The example of ‘gatekeeping’ is more likely to lean towards health persuasion than personal counselling.

Understanding and visualising promotional strategies and where the paramedic is situated, both as an individual and a community health professional is helpful in identifying areas where paramedics can contribute and promote a healthy childhood. Table 1 offers some areas that encourage paramedics to reflect, and potentially incorporate these within their practice.

| Individual (during consultation) | Community (outside consultation) |

|---|---|

|

|

|

Case example: smoking and childhood

Smoking is now widely regarded to impact health across the lifespan (Jha and Peto, 2014), where parental and childhood smoking can affect a child's weight, sudden infant death syndrome, respiratory infections and asthma, and cancer (Faber et al, 2016; Aucott et al, 2017). In the UK, smoking costs the NHS approximately £2.5 billion (Department of Health of Social Care (DHSC), 2017), and is more prevalent with low socioeconomic status (Smith et al, 2018). The government has aims to create a smoke-free generation, reducing smoking in 15-year-olds from 8% to <3% by 2022 (DHSC, 2017).

The following promotional strategies have been adopted according to the WHO Ottawa Charter:

In healthcare, the Make Every Contact Count consensus statement highlights the importance of health services and clinicians in providing smoking cessation support in order to promote an individual's health and wellbeing (PHE, 2016). All paramedics then ought to discuss with individuals of all ages the health risks of smoking to themselves and others such as children, and encourage them to access a smoking cessation programme.

Conclusion

Health promotion covers a range of individual and community empowerment activities that paramedics in all settings can contribute towards and influence. Policy that implements individual and community disempowerment without supportive evidence is an area that requires attention, and the instance of ‘children under 2 must be conveyed’ is a particular example that needs review. Most paramedics will also be in a clinical role which enables them to engage in a conversation with a child and family, and encourage healthy behaviours. It is important to focus primarily on empowerment, as an authoritative position could be construed as highlighting an individual's behavioural flaws or parenting styles.

Resources recommended to further develop child health promotion strategies are:

The next and final article in this series focuses on child protection, and ensuring that all children feel safe to develop and thrive in society.