In recent years, disaster preparation has become a growing area of research owing to the increasing incidence of disasters and the need to maintain health service provision in such situations (Kocak et al, 2021; Ciottone, 2023). According to the World Meteorological Organization (2021), weather-related disasters have increased fivefold over the past 50 years and the United Nations Office for Disaster Risk Reduction projects that the 350–500 medium-to-large scale disasters occurring every year over the past five decades will rise to 560 by 2030 as a result of increasing human activity and behaviour changes such as agricultural practices, deforestation and land use change, fossil fuels for energy, transportation, and industry (World Health Organization (WHO), 2017). The impact of the increasing number of disasters potentially will place a higher burden on healthcare systems.

The WHO (2017) defines a mass gathering event (MGE) as ‘an organized or unplanned event where the number of people attending is sufficient to strain the planning and response resources of the community, state or nation hosting the event’.

MGEs usually happen at a specific place within a defined time period. While they can present great opportunities for the hosting community, they can also increase the risk of mass casualty incidents where injuries and even deaths occur (Ahmed and Memish 2019; Memish et al, 2019).

Major incidents where there is a sudden surge of casualties can pose substantial threats to healthcare systems, including putting a strain on resources and causing potential delays in response to emergencies (WHO, 2015; Murphy et al, 2021). In addition, the World Meteorological Organization (2021) notes that disaster management preparation has saved many lives, but acknowledges that some people still die despite these efforts. Therefore, it is crucial that health professionals are sufficiently prepared to respond to disasters and handle mass casualty incidents during MGEs.

MGEs take different forms and can vary in many respects, such as the in context and number of participants (WHO, 2015). Mass gathering disasters may be related to human factors such as stampedes and terrorist attacks, or natural causes such as earthquakes, heatwaves and floods that occur during an MGE (Zibulewsky, 2001). As a result, not all risks of mass gatherings can be eliminated; however, disaster preparedness can reduce the extent of incidents at them (Koski et al, 2021). As MGEs present varying risks of disaster, different types of preparedness are required, suggesting a need for context and event-specific research on health preparedness.

Emergency medical services practitioners, including paramedics, nurses and physicians, play a critical role during disasters. As the first responders, they administer life-saving care and support ranging from first aid to critical care and other health-related services to casualties (Hsu et al, 2006). To successfully respond to mass gathering disasters and provide the required healthcare services effectively, practitioners should be adequately prepared for disaster management in terms of knowledge, skills and expertise (Lund et al, 2011).

Therefore, this scoping review aims to examine the current literature on healthcare professionals' disaster preparedness within the context of mass gatherings.

Methods

Scoping reviews, as their name implies, are used to determine how much progress has been made in a particular area of research. In order to explore the question ‘What is known about the preparedness of health professionals for disasters during MGEs?’, a scoping study was conducted to evaluate the extent, quality and nature of the literature.

This scoping review was conducted according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) guidelines (Tricco et al, 2018). The five steps of the framework are: posing a research question; finding relevant studies; selecting studies; charting data; and, finally, organising and reporting findings. Section 11.1.3 of the Joanna Briggs Institute Manual for Evidence Synthesis sets out the improvements made to this framework by Peters et al (2020).

Inclusion criteria

Articles included in this scoping review consisted of primary research exploring disaster preparedness for mass gatherings by any type of health professional involved in disaster response and management. In addition, studies were included if they focused on disaster preparedness during mass gatherings in any setting, were peer reviewed and had full text available for review.

Studies were included if they were published between 2011 and the end of 2022. Finally, only articles published in the English language were selected to avoid potential errors in translation.

Exclusion criteria

Articles that dealt with system-level disaster preparedness, such as those for hospital emergency departments, were not included. This review did not include any grey literature. Since books may include references to sources that did not meet the inclusion requirements, they were also excluded.

Search criteria

An initial search for the literature was conducted on Scopus, CINAHL, PubMed and MEDLINE databases via Ovid to identify all relevant articles examining disaster preparedness among health professionals during mass gatherings.

The databases were searched using the search string: [disaster AND prepare*] AND [health professional OR doctor OR nurse OR medic OR paramed* OR health personnel OR hospital OR health] AND [mass gathering* OR crowd OR pilgrim*].

Articles selection

Following the PRISMA-ScR approach (Tricco et al, 2018), the online Covidence systematic review software was used to facilitate article selection.

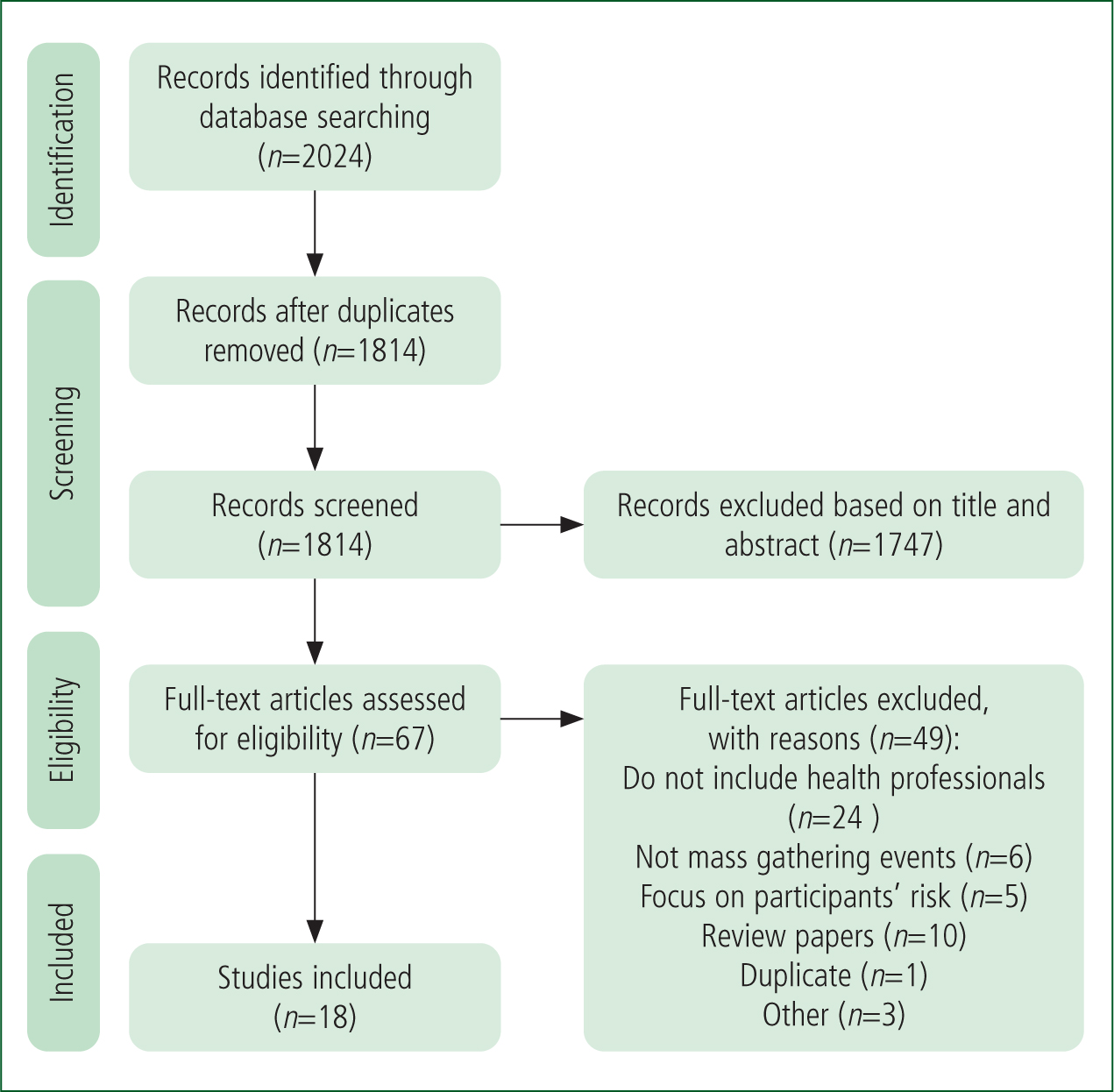

After removing duplicate articles, two reviewers (IA and DGE) independently screened the titles and abstracts of the remaining articles for eligibility. These two reviewers also independently evaluated full texts of the selected articles. Conflicts were resolved by discussion; when agreement could not be reached, this were resolved based on the opinion of a third independent reviewer (LS), who acted as an arbiter. Figure 1 shows the article selection process.

A total of 2024 references were identified from the combined database search, of which 210 were duplicates and removed. Therefore, 1814 articles remained to be screened for relevance based on title and abstract. The screening found 1747 articles to have irrelevant titles/abstracts that did not address the research question so were excluded. This left 67 articles for full-text screening, of which 49 did not meet the inclusion criteria and were excluded. Consequently, 18 articles were finally selected and included in the scoping review.

Data were extracted from the qualifying studies through data charting with the help of a data extraction sheet, developed by the authors, to collect key information about the studies. The following information was recorded for each study: author(s); year of publication; location/context; methodology (including data collection instruments and analysis methods); findings; limitations; and implications (Table 1). The articles were closely reviewed and analysed to determine their findings, significance and limitations. The extracted data were analysed using thematic analysis and presented in a narrative form.

| Author(s) and year of publication | City/state, country | Purpose | Methodology | Participants and sample size | Findings | Limitations | Implications/recommendations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Joseph et al (2016) | Kerala, India | Identify the potential health risks and main difficulties faced by health professionals in relation to mass gatherings at Sabarimala temple, Kerala, India | Qualitative, in-depth interview and document reviews | Doctors (n=46) | Work stress is a major concern and frequent transfers affect disaster preparedness Only 28% had training for mass gathering health management | Specific to the Indian context; unclear sampling method and low response rate (38%) | Suggested use of a risk-ranking tool in regard to assessing risks related to religious mass gatherings |

| Rossodivita et al (2016) | Milan, Italy | Report direct experience in the planning and response to disasters during EXPO 2015 in the Lombardy region, Italy | Observation study | All healthcare teams involved in disaster management (no definite n) | A specific training programme and drills were provided for all EXPO health workers to improve preparedness | Findings reported based on experience of the events | Implement training and exercises on emergencies for all who could be involved in them |

| Alzahrani and Kyratsis (2017) | Mecca, Saudi Arabia | Assess hospital emergency nurses' knowledge, role awareness and skills in disaster response with respect to the Hajj mass gathering in Mecca | Quantitative, cross-sectional online survey | Nurses (n=106) | High level of awareness about clinical role in disaster response but limited knowledge and awareness of wider hospital emergency and disaster preparedness plans | Cross-sectional design, relatively small and non-random sample, and use of self-reported data | Three key training opportunities to develop disaster management skills: hospital education sessions; emergency management course; and short courses in disaster management |

| Al-Shareef et al (2017) | Mecca, Saudi Arabia | Evaluate hospital disaster plans in the city of Mecca | Quantitative, cross-sectional survey | Hospital directors of disaster planning (n=14) | Staff knowledge and training is part of hospital disaster preparedness | The questionnaire was not sufficiently peer reviewed nor pilot tested and the sample was small. | Hospitals should review disaster management plans; further research needed |

| Nofal et al (2018) | Riyadh, Saudi Arabia | Assess the knowledge, practices, and attitudes regarding disaster and emergency preparedness of emergency department staff at a tertiary hospital | Quantitative, cross-sectional | Emergency department physicians and nurses (n=189) | Knowledge of disaster preparedness. Majority felt training (98.4%), simulations (87.3%), and drills (100%) are necessary for preparedness | Self-reported data; data collected from one hospital, so lack of generalisability and transferability; no pilot testing or peer-review of the invented tool | Follow-up research is necessary for maximising emergency department preparedness |

| Johnston et al (2019) | Queensland, Australia | Describe clinical staff perspectives of structures and processes required for an in-event health care service operating during the Gold Coast Marathon | Pragmatic qualitative, semi-structured interviews | Doctors, senior nurses and nurses (n=12) | Staff should need the knowledge, skills, experience, and expertise to work independently. Staffing allowed for capacity building and adequate staffing | Self-reported data; small sample size; qualitative data; data related to only one event; sparse discussion of disaster preparedness | |

| Karampourian et al (2019) | Karbala, Iran | Investigate factors that contribute to a health system's preparedness for incidents during a religious mass gathering | Qualitative, unstructured and semi-structured interviews | Key informants: executive managers, policymakers and pilgrims (n=22) | Medical personnel should be familiar with religious mass gatherings and rapid response forces should be trained | Lack of generalisability and transferability | Education should focus on risk types and pilgrim behaviour, and include scenarios for managers |

| Falatah et al (2021) | Mecca, Saudi Arabia | Explore the lived experience of transcultural Muslim nurses providing medical care to diverse pilgrims for the first time during the 2018 Hajj season | Qualitative, phenomenological study | Nurses (n=11) | Transcultural nurses need more training to improve their ability to provide care during Hajj | Only transcultural Muslim nurses included; small sample size; qualitative data; subjective data; methods not clearly explained; and little discussion of disaster preparedness | Transcultural nurses need further orientation for the Hajj; equipment and strict policies that reinforce professionalism and commitment are needed |

| Koski et al (2020) | Helsinki, Finland | Investigate what factors the rescue authorities say need to be considered when preparing for mass gatherings | Qualitative, semi-structured interviews | Rescue authorities (n=15) | Three main factors: cooperation in the pre-planning phase; factors in the emergency plan; and actions during the event | Qualitative data so not generalisable or transferable | The dispersion of workload during the event needs further investigation to facilitate the effective use of limited operative resources |

| Sultan et al (2020a) | Southern Saudi Arabia | Assess the theoretical and practical major incident and disaster readiness of emergency nurses in southern Saudi Arabia | Quantitative, cross-sectional survey | Nurses (n=200) | Good knowledge of the theoretical dimensions of the Emergency Preparedness Information Questionnaire but uncertainty over skills, practical performance and evaluation of own abilities | Data collected in one region; lack of generalisability; self-reported data | Need to boost practical emergency preparedness exercises and practical and theoretical knowledge |

| Sultan et al (2020b) | Southern Saudi Arabia | Evaluate healthcare workers' perceptions of their preparedness and willingness to work during disasters and public health emergencies in the southern region of Saudi Arabia | Quantitative, cross-sectional survey | Emergency health staff: nurses, physicians, administrators, paramedics and supportive services (n=213) | Varied level of knowledge about different disasters. Training and knowledge of disaster management influence willingness to work during disaster situations | Survey tool was English version, so unsure of appropriateness for linguistic background(s) of participants. Lack of transferability and generalisability | Future contingency and disaster plans should include detailed information concerning all important factors |

| Al-Wathinani et al (2021) | Mecca, Saudi Arabia | Explore emergency medical service providers mass gathering disaster preparedness information sources and to determine educational resources for the providers | Quantitative, web-based cross-sectional survey | Saudi Red Crescent Authority providers: first responders, technicians, paramedics, physicians (n=700) | Source of information for disaster preparedness include real disasters, disaster management course and training | No space for free text so respondents could not add topics they felt relevant | Need for continuing education. Simulated disaster drilling for novices is necessary to improve mass casualty disaster response |

| Ghazi Baker (2021) | Medina, Saudi Arabia | Assess disaster preparedness of nurses working in government hospitals in Medina, Saudi Arabia | Quantitative, cross-sectional survey | Nurses (n=330) | Those who received training were better prepared than those without training | Only nurses working in government hospitals; quantitative data; self-administered questionnaire | Further research is necessary to examine disaster preparedness, especially in specific areas and settings |

| Brinjee et al (2021) | Taif, Saudi Arabia | Identify nurses' emergency and disaster training and education needs | Quantitative, cross-sectional survey | Nurses (n=210) | Nurses with little experience lacked knowledge on disaster triage and in drills. They need disaster education and training in three areas: incident management systems, disaster triage, disaster drills | The questionnaire was not piloted; self-reported data; and purposive sampling | Disaster education should be included in nursing curricula |

| Koski et al (2021) | Helsinki, Finland | Investigate all aspects of preparedness for mass gatherings from a multi-sector expert board's point of view | Quantitative, Delphi questionnaire | Multi-sectoral expert board (n=25) | On-site medical personnel should have adequate levels of skills for mass gatherings | Predicting authorities' workload requires further research to enable more accurate resource deployment | |

| Mobrad et al (2022) | Riyadh, Saudi Arabia | Assessing Saudi Red Crescent Authority practitioner perceptions and knowledge of disaster management and response | Quantitative, descriptive, cross-sectional | Practitioners: paramedics, emergency medical service technicians and physicians (n=302) | Moderate preparation in using pre-disaster protocol, skills on disaster management and abilities to evaluate disasters | 56.9% response rate; self-reporting data | Incentives to extend education regarding their role, scope of practice, and skills as medical staff in disaster situations |

| Campanale et al (2022) | Matera, Italy | Revise a hospital's mass casualty incident plan and start a programme to increase awareness of it | Quantitative | All hospital personnel: physicians, nurses, managers, as well as healthcare and non-healthcare assistants (n=193) | The educational programme improved knowledge and capacity to function in active roles during a mass casualty incident | Self-evaluation of knowledge and skills; unclear evaluation methods or peer-review evaluation; no pilot study | The educational format seems to be adequate to review and improve existing plans and transfer specific skills |

| Yassine et al (2022) | Beirut, Lebanon | To explore the dynamics of healthcare provision during recent unplanned public mass gatherings in Beirut, and how the healthcare system adapts to mass protests | A qualitative study using semi-structured interviews | Various fields and backgrounds who volunteered at medical tents: (n=12) | The study identified themes on preparedness, case type and recommendations, highlighting lack of knowledge, resources, and organisation among practitioners during unplanned mass gatherings. | Small sample size, potential selection bias, lack of generalisability to other contexts, and possible recall bias in the interviews | On-site healthcare during unplanned mass gatherings is vital. Forming a task force of health professionals led by the government was recommended to plan protocols, train staff and secure resources in advance |

Quality assessment of the articles was not carried out because the purpose of this scoping review was to map the literature, regardless of the quality of evidence.

Results

Studies included in this scoping review were published between 2016 and 2022, reinforcing the inclusion criteria justification that this is an emerging area of research.

The majority of the studies (n=11) were quantitative (Al-Shareef et al, 2017; Alzahrani and Kyratsis, 2017; Nofal et al, 2018; Sultan et al, 2020a; 2020b; Al-Wathinani et al, 2021; Brinjee et al, 2021; Ghazi Baker 2021; Koski et al, 2021; Campanale et al, 2022; Mobrad et al, 2022), while the rest (n= 6) were qualitative (Joseph et al, 2016; Johnston et al, 2019; Karampourian et al, 2019; Falatah et al, 2020; Koski et al, 2020; Yassine et al, 2022) or took an observational study approach (Rossodivita et al, 2016).

Of the quantitative studies, 10 employed a cross-sectional survey design for data collection (Al-Shareef et al, 2017; Alzahrani and Kyratsis, 2017; Nofal et al, 2018; Al-Wathinani et al, 2021; Brinjee et al, 2021; Ghazi Baker, 2021; Sultan et al, 2020a; 2020b; Campanale et al, 2022; Mobrad et al, 2022), while one used the expert questionnaire method (Delphi technique) (Koski et al, 2021). The observational study approach (Rossodivita et al, 2016) used simulations to evaluate several studies that were conducted by different institutions and researchers on hospital preparedness for mass gatherings.

In terms of participants, eight studies included two or more types of health professional including first responders, technicians, paramedics, physicians and nurses (Rossodivita et al, 2016; Nofal et al, 2018; Johnston et al, 2019; Al-Wathinani et al, 2021; Sultan et al, 2020a; 2020b; Campanale et al, 2022; Mobrad et al, 2022; Yassine et al, 2022), while five included only nurses (Alzahrani and Kyratsis, 2017; Falatah et al, 2020; Sultan et al, 2020a; Brinjee et al, 2021; Ghazi Baker 2021) and one, only doctors (Joseph et al, 2016). Three studies involved multiple types of staff including authorities, managers and policymakers (Al-Shareef et al, 2017; Karampourian et al, 2019; Koski et al, 2020).

Others included individuals responsible for disaster planning, such as hospital directors (Al-Shareef et al, 2017), rescue authorities (Koski et al, 2020), a board of experts (Koski et al, 2021), health system managers and experts involved in planning and managing health services for the religious mass gathering and pilgrims (Karampourian et al, 2019), and practitioners volunteering at medical tents during protests in Beirut (Yassine et al, 2022).

In the included studies, sample sizes ranged from 11 to 700. The majority of the studies (Zibulewsky, 2001) were conducted in Saudi Arabia, followed by four in Europe (Finland: 2; Italy: 2), and one each in Australia, India, Iran and Lebanon.

These studies highlight the importance of disaster preparedness in healthcare settings during mass gatherings, and demonstrate an emerging interest in this field across multiple regions and contexts.

Themes

The studies included in this scoping review covered various aspects of health professionals' preparedness for disasters during mass gatherings. The level of this was reported in eight studies (Alzahrani and Kyratsis, 2017; Nofal et al, 2018; Sultan et al, 2020a; 2020b; Brinjee et al, 2021; Ghazi Baker, 2021; Mobrad et al, 2022; Campanale et al, 2022). Other studies reported factors influencing preparedness (Koski et al, 2021; Brinjee et al, 2021; Ghazi Baker, 2021; Johnston et al, 2019; Karampourian et al, 2019; Yassine et al, 2021), sources of information for disaster preparedness (Alzahrani and Kyratsis 2017; Al-Wathinani et al, 2021), and strategies to improve disaster preparedness (Campanale et al, 2022; Yassine et al, 2022).

Finally, five studies examined the risks and challenges associated with health professionals' participation in MGEs (Joseph et al, 2016; Falatah et al, 2021; Campanale et al, 2022; Mobrad et al, 2022; Yassine et al, 2022).

Four main themes were identified from the reviewed studies: level of preparedness; factors influencing preparedness; strategies for improving preparedness; and risks associated with participating in MGEs.

Practitioner level of preparedness

The studies that examined the level of health professionals' disaster preparedness were conducted in different regions, with a significant number of studies conducted in Saudi Arabia; studies were also conducted in Lebanon (Yassine et al, 2022) and Italy (Campanale et al, 2022). An average level of disaster preparedness was found among nurses in Medina (Ghazi Baker, 2021). Similarly, most medical staff of the Saudi Red Crescent Authority (SRCA) were found to be moderately prepared for disasters, with fewer than half (48.7%) reporting being prepared for terrorism disasters (Mobrad et al, 2022). Moreover, most of the SRCA staff reported moderate levels of knowledge and skills for disaster management and disaster evaluation abilities. Only 43.4% were aware of a disaster or emergency plan at their workplace, and 37.4% felt confident that the plan would work well in a disaster.

In contrast, the study conducted in Beirut, Lebanon, found that healthcare workers lacked knowledge in field medicine protocols and an organisational structure, and faced difficulties securing equipment and advertising their services (Yassine et al, 2022). In the Mecca region, emergency nurses were found to have a high level of awareness about clinical roles in disaster response, but limited knowledge and awareness of wider hospital emergency and disaster preparedness plans (Alzahrani and Kyratsis, 2017).

Sultan et al (2020a) found that emergency department nurses in the southern region of Saudi Arabia had a good knowledge of the theoretical dimensions of the Emergency Preparedness Information Questionnaire in major incidents and disasters but were uncertain about their skills in handling a disaster in reality. Nofal et al (2018) also identified a satisfactory level of knowledge and understanding of the concepts and principles of disaster management and preparedness, however not much experience/confidence in applying them in practice. The authors suggested that this could be due to the lack of regular training and drills, as well as the low frequency of disasters in their setting. Finally, Sultan et al (2020b) found healthcare staff had varying levels of knowledge for different disaster scenarios, such as bombings, mass shootings, chemical incidents and biological and nuclear incidents.

Factors influencing preparedness

Johnston et al (2019) suggested that staff experience and knowledge were crucial elements of disaster preparedness for MGEs.

The most reported factors found in this scoping review that influence health professionals' disaster preparedness were previous experience and training. Nofal et al (2018) found that practitioners with more experience (>5 years) had a greater knowledge of disaster and emergency preparedness. However, Mobrad et al (2022) found that experience of a real disaster had a significant effect on health professionals' post-disaster management abilities but not on disaster preparation and evaluation.

Confidence in the effectiveness of disaster plans was associated with perceived preparedness, knowledge and skills for disaster management, while age and education had no significant influence on perceived preparedness for disasters (Mobrad et al, 2022). This was also reflected in the study from Italy (Campanale et al, 2022), which noted the importance of simulations, ed1ucational courses and questionnaires in boosting the individual capacity to function in active roles during a mass casualty incident. Similarly, Sultan et al (2020b) identified training and knowledge of disaster management positively influenced health workers' willingness to work during disaster situations.

Strategies to improve preparedness

The most commonly reported approach to improve health professionals' disaster preparedness with respect to knowledge and skills was training and education.

According to Karampourian et al (2019), medical personnel working in MGEs should be familiar with such events and be trained. Koski et al (2021) also noted that the on-site clinical personnel should have adequate levels of skills that match the event type and the participation rate (being able to handle the expected number and severity of health issues that may arise). In this respect, Rossodivita et al (2016) noted that drills involving different exercises and scenarios to test and manage the whole chain of emergency contributed to the preparedness of health professionals and others engaged in the emergency response preparedness for disasters. The majority of the participants in Nofal et al (2018) also found that training (98.4%), simulations (87.3%) and drills (100%) were necessary for disaster preparedness; 81% had taken part in disaster drills at their hospital. Furthermore, Campanale et al (2022) found that an educational programme to increase practitioner awareness about a revised mandatory hospital Emergency Plans for Massive Influx of Patients in Italy (Piano di Emergenza per il Massiccio Afflusso di Feriti) and providing specific training for mass casualty incident management improved hospital staff knowledge and skills to function in active roles during mass casualty incidents.

Overall, the sources of information about disaster preparedness included genuine disasters, drill practice, training and disaster management courses. Additional sources include disaster management protocols, on-site visits, information websites, information pamphlets, co-workers, friends and families, and the media.

Risks associated with practitioner participation in mass gathering events

Health professionals found that participating in MGEs was associated with various risks and challenges.

In particular, 76% of participants in Joseph et al's (2016) study reported that disasters related to mass gatherings were stressful and that frequent staff transfers affected their ability to build competencies in dealing these. Although preparedness for stressful conditions is essential, only 28% had received training for mass gathering health management.

Transcultural nurses in Falatah et al's (2020) study reported a lack of training, such as on the use of machines and equipment in the Hajj healthcare facility and orientation to the place, as difficulties during participation in Hajj. Mobrad et al (2022) also identified a lack of regular disaster drills as a hindrance to disaster preparedness.

Discussion

The findings of this scoping review demonstrate the literature on the disaster preparedness of health professionals in the context of MGEs is limited. Studies examining the knowledge and skills of practitioners in managing mass gathering disasters, primarily conducted in different regions of Saudi Arabia, showed inconsistent results. The preparedness of health professionals varies in many ways, including regionally and among the professionals such as nurses, doctors and paramedics (Cutter et al, 2010; Nofal et al, 2018; Mobrad et al, 2022).

Complementary insights from other international contexts (Campanale et al, 2022; Yassine et al, 2022) highlight the complexity of preparedness in unplanned mass gatherings and the effectiveness of dedicated disaster management protocols and personnel training. These studies emphasise the importance of context-specific training, resource allocation, and the development of comprehensive disaster management protocols for effective disaster preparedness in mass gatherings.

There is considerable knowledge about the clinical role in disaster responses (Alzahrani and Kyratsis 2017). However, as Mobrad et al's (2022) findings indicate, most participants were only somewhat prepared to use pre-disaster protocols, had only moderately developed skills in disaster management and their abilities to evaluate disasters were inadequately developed. Therefore, additional training for practitioners working in MGEs is necessary (Mobrad et al, 2022). The review further identified that strategies for improving health disaster preparedness might vary between different events and context such as culture and language.

Overall, the limited and inconsistent literature indicates a lack of understanding of disaster preparedness for health professionals in MGEs. Consequently, there is a need for context-specific studies. All the studies used a quantitative or qualitative method (although Campanale et al used mixed methods), confirming the need for studies utilising a broader range of data collection and analysis methods to enhance the research evidence's quality and reliability.

The overall quality of the methodological approaches employed by the studies may be low, with some studies having unclear methodologies, including sampling methods and interview techniques (Alzahrani and Kyratsis, 2017; Al-Shareef et al, 2017; Nofal et al, 2018; Al-Wathinani et al, 2021). Three quantitative studies (Al-Shareef et al, 2017; Brinjee et al, 2021; Campanale et al, 2022) also employed data instruments that did not have reported validity or reliability, and only one was pilot tested (Joseph et al, 2016).

The use of self-reported data and subjective self-assessments in some studies might have contributed to a high risk of bias, resulting in overall high levels of disaster preparedness (Alzahrani and Kyratsis, 2017; Nofal et al, 2018; Johnston et al, 2019; Sultan et al, 2020a; 2020b) as opposed to lower levels in studies that incorporated non-subjective data. This discrepancy may suggest that participants in some populations may overestimate their own preparedness.

Limitations

The main limitation of this scoping review is that it includes only articles published in the English language, and other relevant studies may have been excluded.

The quality of the evidence was also not evaluated as the aim was to explore the amount of literature on health disaster preparedness.

Conclusion

Disaster preparedness is a growing area of research, with several studies being published in recent years.

However, the body of research on health professionals' disaster preparedness for mass gatherings remains sparse.

Most of the studies purport to be about disaster preparedness for mass gatherings but, in reality, focus on something other than this topic, revealing a clear knowledge gap that should be investigated further.

Implications for research

This scoping review demonstrates that there is a need for further research in all geographical areas with the increasing MGEs globally, specifically in regard to preparedness.

Such future studies should employ more rigorous research methods, including quantitative and qualitative approaches and better sampling strategies to improve the quality and significance of the evidence. Tools developed or adopted to measure disaster preparedness should be more objective and less reliant on subjective, self-reported data.

Implications for practice

Although there is still a need for research to inform practice, the results of this scoping review emphasise the benefit of continuing education and training for health professionals to develop the skills required for effective disaster management during mass gatherings.